Alien Minds

Asher here. Outer space, I have often remarked, is fantasy of colonization. We leave the crowded old world in imperfect ships, making dangerous voyages in search of new lands on which to build and reshape to our will. These lands will, of course, be empty, terra nullius, to do with as we see fit. We will settle them, strip them of their resources, and use them to fuel our way out to the next world, and the next. What is the frontier there for, if not to be tamed? What is emptiness for, if not to be filled? We call it space because that’s what it offers: endless room for us to roam, and for our children to roam. It is mankind’s destiny to go among the stars.

So it's interesting, isn't it, the stories we tell of what happens when the stars come to us. Stories of vast ships appearing out of nowhere in our skies, bearing technology we cannot match, opening us to their designs like a knife blade opens an oyster. Of metal leviathans sliding through the soundless void between creation, each a predator nation consuming everything in its path. Of cold-eyed things that look at us and see nothing sapient, nothing alive, who perform horrors upon us and call it science, who take our men or our women, who use us like beasts, who kill us in pursuit of their own relentless expansion. Of things we meet during our own wanderings in the outer black, on planets we have claimed but hold no claim on; things that see our bodies as nothing more than meat if we’re lucky, and nests if we’re not. All of which speaks, perhaps, to a latent anxiety: that the final frontier is endless. The final frontier is hungry.

Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that knows there's more than one way to conceptualize an alien. "If a lion could speak," philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once observed, "we would not understand him." Sometimes, the alien from outer space is not a bleak mirror of our own history reflected back on us; sometimes, it is simply creatures with agency and minds unlike our own; entities we can only imperfectly understand, whose behavior we can't always predict or recognize. And as Jordan Peele's masterpiece film Nope argues, the line between the aliens of Earth – the bestiary of things we call animals – and the aliens of the stars is very, very thin.

Shortly after seeing (and loving) Nope, I got to talking with writer KM Nelson about the film, and about the clever way the film approaches the idea of animals as aliens, and aliens as animals. So today, on the anniversary of the film's release, we just had to commission her to talk about it.

It's Heat Death. Stay with us.

Jean Jacket Did Nothing Wrong

KM here. In the sky over the dusty California town of Agua Dulce, an alien unfurls. What had once appeared to be a flying saucer shifts shape before the viewer’s eyes. Topped by a billowing sail, his diaphanous form floats effortlessly in the air, with an undulating train that extends across the landscape. At his center, a square eye emerges, its snapping green ribbons a stark contrast to his muted gray body. He’s angelic, both in the biblical and Evangelion sense: a revelation, unveiled in glory and terror to menace the two humans on the ground below.

Various species perform startle displays, either bluffing to scare off a perceived threat or as a precursor to other defensive behaviors. Examples include the puffed-up feathers and dramatically extended wings of the Great horned owl and the acrobatic handstand of the Spotted skunk. The aforementioned transformation has real-world parallels — the female Blanket octopus unfolds a set of webbed tentacles when threatened, forming a lengthy, ballgown-esque train, and the Giant honey bee colony pulses rhythmically during its shimmer defense.

The alien is “Jean Jacket,” the principal threat of Nope, Jordan Peele’s third film. And notably, at this moment of climactic confrontation, he is not acting like a monster. He’s acting like an animal.

In the stories humans tell, our primacy is a foregone conclusion. We might stuff our tales with animals — living or dead, real or mythical — but when we do, they tend to serve as props, stand-ins, signifiers, threats. Quite often, they’re framed as monsters. This treatment is so standard that it can be difficult to see, much less question.

Which is what makes Nope such a remarkable viewing experience. Amidst Peele and his team’s clever recontextualization of alien abduction stories and musings on the bloody cost of spectacle, the movie’s creators find time to do something unusual: to render an animal as itself.

For much of Nope’s runtime, Jean Jacket is objectified — considered a UFO by the humans he encounters. It is only near the film’s end that the creature is given a name, and described as not just an “it” but a “he.” (That being said, the film never confirms Jean Jacket’s sex, or even whether or not he has one. He’s an alien, after all. I’m choosing to go with “he” for simplicity.)

As so often with animals, the people in Jean Jacket’s orbit want to use him as a tool for their own ends, intending to make him into a spectacle for human consumption. Two-bit impresario Jupe (Steven Yeun) develops a weekly live performance at his theme park with Jean Jacket as its star, describing him in a monologue as a flying saucer, while Haywood siblings Em (Keke Palmer) and OJ (Daniel Kaluuya) take the documentarian route, setting up cameras on their ranch to capture evidence of his presence and get their “Oprah moment” — a shot at fame, and presumably accompanying fortune.

Unbeknownst to the people of Agua Dulce, Jean Jacket is not a mode of transport crewed by a perhaps-benevolent alien species, but an individual in his own right. While his exact origins are left ambiguous, he can certainly be described as “out of this world” — the likelihood that this creature evolved on Earth is slim to none. His behavior, however, is recognizable as that of an apex predator.

Members of Nope’s film crew have emphasized the importance of taking a grounded approach to designing Jean Jacket, incorporating attributes from animals to create a creature that would feel real to the audience. The team included several scientific consultants, among them Kelsi Rutledge, who was completing her Ph.D. at UCLA at the time of filming. In an interview published by UCLA’s Newsroom, Rutledge laid out some of the natural inspirations for Jean Jacket. His flying saucer form is informed by the anatomy of the sand dollar, and his camouflage among the clouds maps to octopus’ use of chromatophores to conceal themselves. In his unfurled shape, we see the influence of the bigfin squid, a deep-sea invertebrate with lengthy tentacles and large fins (hence the name). His digestive system — highlighted in a tremendously disturbing sequence in which human victims struggle and scream within his body — is modeled on a combination of birds and a marine invertebrate called the giant larvacean.

As presented to us, Jean Jacket is a stealth predator. He conserves energy by hovering in place and disguising his body in a stationary cloud, a puff of condensation somehow immune to buffeting winds. His balletic flight movements resemble a sea creature gliding through water, and he emits a field that disrupts electronics in a wide radius. His disc-shaped body has a large orifice at its center. Within, an eye points downward to perceive potential targets (or threats, as the case may be). When he hunts, he uses the clouds as cover before descending to capture prey by whipping up a tractor beam–esque whirlwind to pull his intended meal into his perpetually gaping maw. Notably, he is reactive to eye contact: when someone gazes at him, he responds. He attacks both living creatures and inanimate objects with eyelike markings, including a decoy horse that becomes lodged in his body.

It is undeniable that Jean Jacket is an antagonistic force in Nope. Between the approximate crowd size of the premiere of the Star Lasso Experience, the ominous reports of missing hikers and other onscreen deaths, he kills, at minimum, 50 people. However, what sets him apart from other horror movie creatures — including ones that inspired Peele’s vision for Nope — is that he always behaves as an animal, surviving according to his biological principles. Because his portrayal is grounded in the natural world, Jean Jacket’s behavior is recognizable, allowed to be “other” without becoming either anthropomorphized or excessively monstrous. He is worthy of wonder, and respect — both for his dignity as a living being and in light of the clear danger he presents. Decenter the perspective of the film’s human stars in favor of Jean Jacket, and we’re left not with a pitiless villain, but a tragic figure.

The key to Jean Jacket is found in Nope’s other dangerous animal, the chimpanzee Gordy who stars in one of the film’s most harrowing sequences. Jupe’s childhood turn on the sitcom Gordy’s Home, we learn, ended in an explosive outburst when the popping of birthday balloons on set startled the show’s chimpanzee star, who attacked his human castmates while Jupe watched in terror from beneath a table. Although it is unflinchingly violent, the flashback to Jupe’s traumatic experience is staged with empathy for the animal at its center. In the immediate aftermath of the attack, Gordy (played in motion capture by Terry Notary) wanders back into frame, coated in blood. Visibly confused, he touches the still form of a young actress he’s grievously injured. Then he reverts to a trained behavior: reaching out to fist bump Jupe before being shot dead.

As staged in the film and evidenced in real life, animals cannot be expected to capitulate cleanly to human desires. Non-domesticated species kept in captivity require a high standard of care, including safety protocols to protect animals and humans alike. Unfortunately, the necessity of such protocols has been proven repeatedly. The Gordy’s Home attack bears similarity to a 2009 incident in Stamford, Connecticut, in which a chimpanzee raised as a household pet mauled Charla Nash. After the attack, a memo surfaced in which a biologist warned state officials about the danger posed by the chimp’s living conditions. Show business has its own share of tragedies. The behind-the-scenes story of the 1981 film Roar — about a naturalist and his family who share their home with lions, tigers and more — is littered with horrifying episodes of cast and crew being injured by animals on set. More famously, Roy Horn of Siegfried and Roy fame was attacked onstage by a white tiger during a 2003 performance in Las Vegas. That animals are unpredictable on set is a truism that Nope establishes very early, when horse trainer OJ’s warnings about one of his animals are ignored and the horse bucks after careless crew startle it.

Peele and others have cited various movies that served as inspiration for Nope, among them Close Encounters of the Third Kind and King Kong. Of Nope’s influences, two films in particular are useful as a frame of reference through which to analyze Jean Jacket’s depiction: Jurassic Park and Alien. Put Nope in conversation with these movies, and their nonhuman antagonists can be placed on a spectrum ranging from monstrosity to animality — from Alien’s unapologetically murderous xenomorph, to the aberrant behavior of Jurassic Park’s velociraptors, to Jean Jacket’s deadly, but naturalistic, predatory instincts in Nope.

Alien’s titular antagonist is, in every way, a monster. It represents annihilation. The spindly creature with an elongated head, double jaws, acid blood and spear-tipped prehensile tail has one thing on its mind: murder. It consumes and reproduces, but its biological functions are important only inasmuch as they drive it to kill in a frightening manner. Someone must die gruesomely for it to be born; after being forcibly implanted by the facehugger, the chestburster enacts its name, erupting from its host in a spray of viscera.

For all that its lifecycle is roughly based on that of real wasps, there is no dignity afforded to the xenomorph. Slick and black, with uncanny, stretched proportions, the inherent wrongness of its humanoid body instills fear in its victims, as well as the viewer. As designed by Swiss surrealist artist H.R. Giger, it possesses a perverse beauty, but the xenomorph is most entrancing not to xeno-naturalists but to a corporation that intends to harness the lifeform’s rapacious appetite for violence as a weapon. “Its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility,” muses the treacherous android Ash. He calls it “a survivor, unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality.”

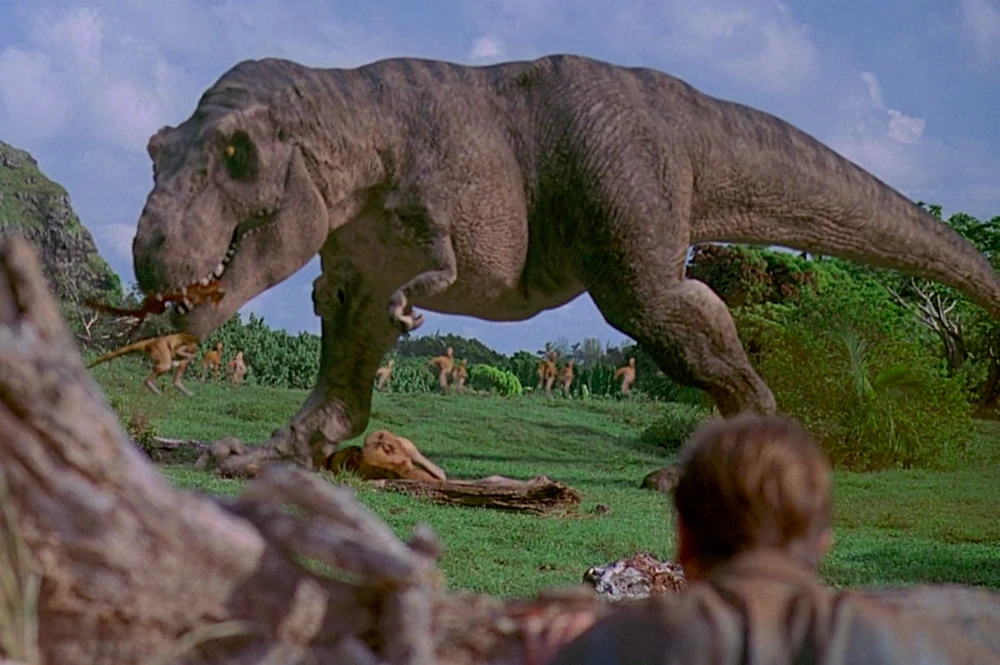

Jurassic Park, meanwhile, is notable for its commitment to portraying dinosaurs with some level of scientific accuracy. Though the film is not immune to Hollywoodization, so to speak — the outsized proportions of the velociraptors an oft-cited example — its depictions of extinct species are grounded in the scientific knowledge available around its release. As interdisciplinary paleontologist Ali Nabavizadeh notes, the movie leaned into the dinosaurs’ naturalism: it “emphasized the active lifestyle of dinosaurs, it portrayed plausible social behaviors, and it even discussed the relationship of modern birds with extinct dinosaurs.”

At its core, in a choice that foreshadows Nope, Jurassic Park treats its extinct cast as animals. Paleontologists Alan Grant (Sam Neill) and Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern) gaze in wonder as a Brachiosaurus lumbers across the plain, then rises on her hind legs to graze from the tops of the trees. On the side of the carnivores, the Tyrannosaurus rex behaves plausibly as a predator across a variety of appearances in the film, even if creative license is taken with the way the dinosaur’s vision functions. When Grant and the children in his care run from a flock of ostrich-like Gallimimus, the Tyrannosaurus ambushes the group, snapping one up, killing it with a shake of her head and beginning to eat while the humans hide behind a large log. She is a hunter, but (unlike the xenomorph) she is not an indiscriminate killer; she remains focused on her meal, and Grant and the children move away without trouble.

But another creature in the movie blurs the lines between naturalistic predator and supernatural monster. The Tyrannosaurus certainly has humans on the menu, but they’re one choice among a smorgasbord of other, potentially more appetizing meals. In contrast, the behavior of the film's Velociraptor skews more monstrous. The three raptors are calculating, displaying an uncanny level of intelligence and problem-solving ability, and they target people relentlessly. In his opening monologue, Robert Muldoon (Bob Peck) lays out their lethal capabilities and “extreme intelligence,” laconically recalling the way they systematically tested the electrified fence of their paddock as part of an attempt to escape.

It’s not that the raptors’ behavior cannot be believed as coming from animals — many species can be alarmingly clever. The “clever girl” who outflanks Muldoon does not possess human intelligence. But her ability to reason reads to the audience as “too human.” The velociraptors’ unwavering fixation on the humans in the park feels like the dogged pursuit of a slasher villain. The raptors cannot be deterred from their intended targets despite a number of obstacles thrown in their way. It’s one thing for them to open a door (although Nabavizadeh points out “the true anatomy of [the species’] wrists would not have allowed it to do so”), but quite another to forgo the instinct for self-preservation and smash through a plate glass window.

Returning to Nope with these touchstones in mind brings Jean Jacket’s characterization further into focus. Jean Jacket lives in the wild (though whether he “belongs” in California is another matter entirely, and beyond the scope of this essay). Unlike the xenomorph and velociraptors — both of whom act with murderous intent — Jean Jacket is not proactive, but reactive. He’s certainly an inherent threat, given his size and indiscriminate approach to feeding.

That approach, in fact, is what brings him into direct confrontation with our species: he’s been baited with food. In “Wildlife Feeding in Parks,” researchers Jeffrey L. Marion, Robert G. Dvorak and Robert E. Manning summarize the dangers posed by food-conditioned wildlife:

Animals that receive human food rewards lose their fear of humans and can become nuisances to visitors, aggressive, and cause human injury and death (Orams, 2002). Individuals have been killed by food-conditioned deer in Yosemite National Park and food-conditioned dingoes in Australia’s World Heritage–listed Fraser Island. Bites from small mammals are common injuries in parks, and disease transmission to humans can occur from bites or close contact (e.g., rabies and Hantavirus, respectively).

Whether he believes his flying saucer pablum or not, Jupe habituates Jean Jacket to human contact while preparing a planned live show at Jupiter’s Claim. He feeds this immense predator on a schedule for six months before dramatically changing the parameters of the encounter — with disastrous results. Upon making his entrance at Jupiter’s Claim, Jean Jacket encounters not just his expected meal (a horse named Lucky), but the direct stares from the dozens of people sitting in the stands. And, as previously mentioned, the film establishes that Jean Jacket is quite sensitive to eye contact.

What happens next: feeding behavior or a territorial outburst? Either way, the end result is the same: he swallows the crowd, leaving only Lucky behind. Now with a full belly, Jean Jacket makes his way to the Haywood ranch, setting up a terrifying encounter with Em, OJ and Fry’s technician Angel (Brandon Perea). Crucially, Jean Jacket does not seem to perceive the humans at the ranch. He is, instead, preoccupied with the screaming mass in his body, which is mixed with detritus from Jupiter’s Claim. While Em and Angel cower inside the house, Jean Jacket hovers over the roof and silences his victims with a single horrible squeeze, coating the building in a shower of blood. Like a cat sauntering onto the nice rug to vomit, the alien ejects the indigestible matter drawn into his body when he attacked the amphitheater, slick blood of his victims flowing from his gullet alongside various inorganic materials. He is not deliberately threatening the people below him: he is simply processing his meal.

At this juncture, Jean Jacket’s killed more people than Alien’s xenomorph and Jurassic Park’s dinosaurs combined (further entries in each franchise notwithstanding). It’d be fair to expect the film to conclude with a vicious battle, pitting humans against a monstrous foe.

But that’s not quite what happens.

OJ, established as someone more in tune with horses than people, pieces together the truth of Jean Jacket’s identity. He’s the one to recognize that they’re dealing with a territorial animal and to give it a name, after one of the horses that used to live on the ranch. “We’re not the reason it settled down here,” he says. “That was Jupe. He got caught up trying to tame a predator. You can’t do that. You gotta enter an agreement with one.”

The Haywood siblings, along with Angel and cinematographer Antlers Holst (Michael Wincott, doing a Werner Herzog riff), make a plan to capture Jean Jacket on film, gathering an array of supplies including a herd of air dancers, a hand-cranked camera immune to Jean Jacket’s electrical interference and an orange sweatshirt with bright green “eyespots” sewn to the hood. The plan does not go perfectly — an interruption by a TMZ videographer ends poorly for the would-be paparazzi — but OJ successfully “[gets] the star out of his trailer.” Mounted on Lucky, he pulls up his hood and takes off at a gallop, drawing the flying disc across the ranch in a heroic sequence straight out of a Hollywood Western. Holst gets the money shot, and OJ releases his secret weapon, a colorful parachute at the end of a long line of flags, which deters Jean Jacket by dint of its association with the decoy he previously ingested.

However, riled by the influx of stimuli, Jean Jacket has an outburst, targeting members of the group with whirlwinds. Then, he begins to change. He expands in form as his membranous tissue unfolds, reaching heretofore unseen proportions: once immense, now colossal.

He has made himself a spectacle.

But this is not a moment of horror, but of awe. The music — a cue titled “A Hero Falls” — is pensive, even gentle, as the Haywoods stand off against the predator. And Jean Jacket? Well, he’s stunning. But at this point, there’s no calming him. Whatever agreement the group intended to enter with him is forfeit.

Taking off on the videographer’s discarded motorcycle, Em speeds to Jupiter’s Claim with the creature in tow, where she releases a giant, cowboy-shaped helium balloon. Up in the clouds, Jean Jacket squares up to the balloon in that strange and beautiful threat display. He engulfs it, and annihilates himself when he pops it inside his body. No music accompanies the moment of his demise. Whatever emotion that arises from his end is left up to us.

The alien predator’s death is a triumph for the Haywoods — they both got the shot and survived. But there’s also reason to mourn, if you’re inclined. Jean Jacket is not evil. He is not a punishment for the hubris of the human protagonists. He is not presented as being particularly malicious. In a world that saw him primarily as an attraction, a prop, a signifier, he’s ultimately none of these things.

He is just an animal who chose the wrong place to make his home.

KM Nelson is a writer and editor who feels as much at home working on the family farm as she does when sitting behind a keyboard. She made various contributions to Radiant Array’s debut visual novel Interstate 35 and is an editor for startmenu.co.uk. You can find her on Bluesky.

This has been Heat Death! This piece was supported by paid memberships to this newsletter. If you'd like to support us – and help us commission more work like this – please consider grabbing a subscription or leaving us a tip.

Want to pitch us? Send ideas to aelbein@gmail.com.

We'll be back soon with more musings on past, future, and all the crises in between. Keep watching the skies.

Member discussion