The Empire is a Predatory Forest

Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that shakes the branches to see what falls out. Thank you so much for subscribing! We've been pretty humbled by the response so far, and we're excited to bring you more of the strange synergies you guys have clearly been craving.

By the time you read this, both Brothers Elbein will be back in Atlanta, in houses bordered and overhung by tall timber and green boughs. Atlanta is sometimes called the "city in a forest," and while that's mostly a real estate slogan, there's still a lot of truth to it. While the same development boom that's metastasizing in cities across the nation has seen a lot of Atlanta's old groves cleared for new housing and businesses, there are still neighborhoods where the air rings with birdsong at all hours of the day. Where the light comes down soft and green, through pine and oak and the spiraling drifts of ivy so beloved by chipmunks and copperheads.

Trees, roads and kingdoms have been on both of our minds this week. Saul has recently returned from a few different trips — Armenia to report about the aftermath of its last, bruising war, New Jersey to visit the pine-wooded estate of in-laws of the DC Soviet — and Asher is reacquainting himself with Atlanta's woodland after driving in from Austin.

The pieces we have for you this week will dig into the connections between all three. We open with two short meditations on the monstrous: specifically, the question of what we act upon, and who acts upon us. (That means carnivorous plants and aliens.) An evening with the sword bros leads us to reconsider the division between East and West. And Asher finds an unexpected connection between the structure of forests and the Empire.

It's Heat Death. Stay with us.

CARNIVOROUS PLANTS AND HUNGRY ALIENS

The Plants are Waiting to Pounce

Consider the carnivore plant from the perspective of those it preys on. The sweet sap smell leads you in until — suddenly — you they are slipping down, down, into a slick-walled, unclimbable pit. Down there the water stings, burns, digests. The leaves snap shut in a cage, salivating pulp pressing soft and spongy against your liquifying body.

From such a seed sprout tales of man-eating trees, toothed flowers, and sweet-talking space seeds crooning for a nibble of blood. It's a pretty straightforward fear, really: the notion that the plant life which surrounds us — omnipresent and foundational enough to define whole biomes — is just waiting for its opportunity to take a bite.

Such a fear is both short-sighted and touchingly naive. Most plants — save those poor species that live in thin soils or the sort of difficult situations that force you to grab your nutrients directly from passing bodies — have no need to act so quickly. We live animal lives: fast, direct, and frantic. Plants can afford to wait for the nutrient pulse, the flow of fertilizer that runs from dropped dung and, above all, decaying carcasses. Life ends and then its essence is quietly passed along through hidden roots and secret bargains. Death feeds plants as much as sunlight. Die in the forest, and the trees will eat you. Die in the meadow, and the wildflowers will bloom that much brighter.

Which is to say: no need to worry about some kind of giant Venus Flytrap. Sooner or later, everyone feeds the plants.

The Hungry Dark

The fantasy of outer space is fantasy of colonization. We will leave the crowded old world on dangerous voyages in search of new planets: true empty land, terra nullius to do with as we see fit. We will change their atmosphere, strip them of their resources, and use them to fuel our way out to the next world, and the next.

The logic lies at the root of our civilization: What is the frontier there for, if not to be tamed? What is emptiness for, if not to be filled? We call it space because that's what it offers: endless room for us to roam, and for our children to roam. It is humankind's destiny, you may have heard, to go among the stars.

And yet we might lay this myth alongside another common one: of what happens when the stars come down among us. Of vast ships appearing out of nowhere in our skies, bearing technology we cannot match, opening us to their designs like a knife blade opens an oyster. Of metal leviathans sliding through the soundless void between creation, each one a predator nation consuming everything in its path. Of cold-eyed things that look at us and see nothing sapient, nothing alive, who perform horrors upon us and call it science. Who take our men or our women, who use us like beasts, who kill us in pursuit of their own relentless expansion. Of things we meet during our own wanderings in the outer black, on planets we have claimed but hold no claim on; things that see our bodies as nothing more than meat if we're lucky, and nests if we're not. Of things in whom their first contact with us awakens an interest, and who follow those fragiles ships and lossy radio signals right back to Earth.

The final frontier is endless, which is another way to say that the final frontier is hungry. For once in our species' nomadic career, it might be better if we stayed put.

EAST MAKES WEST

The oldest story in the world, says Irish historian Michael Clarke, is the one about "the emergence of difference." You see it in the Bible and the Quran and the Just-So Stories: how this became that; how We crystallized out of the broader we.

These stories are ancient, though many have survived as semi-canonical "national epics." How the Jews emerged from the wider society of Canaanite pastoralists: the pact with God, the Burning Bush, the revelation at Sinai. How Christians emerged from the wider society of the late-Roman Eastern Mediterranean: the Crucifixion, the epistles, the martyrs, the ultimate triumph. How Americans emerged from the European maritime cultures scattered across the North Atlantic: Thirteen Colonies, Thanksgiving, Hamilton.

Even today, a lot of public debates are debates over these sorts of narratives. The mid-2000s battle between "creationists" and "evolutionists" was in its heart an argument over competing theories about how difference emerged — as well as a bolster to the stories those groups told about why they were different from each other. Around that same time, in the fever around what became the War on Terror, we were treated to a stampede of Clash of Civilizations style narratives, which argued that a Judeo-Christian West, heir to the cultures of Greece and Rome, was locked in combat — or at least rivalry — with an Muslim/Arab/Persian East.

These narratives are very old, Clarke explained to host Patrick Wyman a couple weeks ago on his popular history podcast Tides of History. They frame popular culture even to this day. They are essential to the West's story of itself: They were a key structural part in the emergence of self-consciously European, and particularly British and French, sense of identity and nation.

And they are also, Clarke explains, almost entirely a misreading of the past. He had gone on Wyman's show to discuss his recent book, Achilles Beside Gilgamesh: Mortality and Wisdom in Early Epic Poetry. In that book, he lays out two stories often assumed to be part of separate Eastern and Western canons. First, from the Greek "West," there is Achilles, the doomed warrior demigod who led the Greeks before the walls of Troy; then, from the Mesopotamian "East," there is the tale of Gilgamesh, the warrior demigod who, upon the loss of his best friend, goes on a quixotic quest for the source of immortal life.

The stories, Clarke tells Wyman, line up in many key elements. There is the hands-on role of gods in human society. The notion of a past Heroic Age when men were men — which caused no end of trouble. The conceit that the work itself is from that age, rather than (still very old) historical fiction. The structure of what one historian has called "the Hero and his Pal," and the emotional beats each narrative hits.

And there is one pivotal scene in each, in which Gilgamesh/Achilles reaches down to the fallen body of his best friend (and, perhaps, lover) Enkidu/Patroclus. He feels for the heart; finds it still; and then wails — in each — like a lioness who finds her cubs taken by a hunter.

To Clarke, the correct read is the obvious one: that this isn't coincidence or shared motifs, but a sign of deliberate artistic choice. That when Homer composed the story of Achilles in the Iliad, he was riffing on Gilgamesh, a work with which we can assume he — and his audiences — would have been familiar.

The interview is worth a listen, less for the specific claim that Clarke makes about those two heroes but for the larger question that raises: namely, why we would assume that East and West were separate at all. In virtually every way — religiously, linguistically, culturally, economically — the Eastern Mediterranean, Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Syrian coast, North Africa, have always been one world, bound together by trade, correspondence, marriage, and military predation.

And for a very long time, Greece — let alone Rome, or England, or any other poles of what we now call The West — was a far dim half-savage star on the outer rim of the Eastern trading world. By legend, its alphabet was brought by the Phoenician prince Cadmus — Clarke calls him a "Syrian refugee." We know the Greeks were perennial traders and colonists, setting up new settlements from Anatolia to Italy to Spain; we know that they took words, concepts, stories, slaves, gods from the East. For example Adonis — the hunky consort of Aphrodite, Goddess of Love — takes his name from a Semitic word, cognate to the Hebrew Adonai, "Lord." In Babylon, Adonis' home country, he is Tammuz, the consort of Ishtar.

The connections go further: both of these names hide out elsewhere in "Western" culture. Ishtar, the Babylonian Goddess of Love, shares her name — somewhat morphed — with the ur-Christian holiday of Easter, with its half-hidden fertility rites. Tammuz shares his name with the fourth month of the Hebrew calendar — in fact, all of the Jewish months have names taken from Akkadian and Assyrian. Each of those months has its own presiding pagan gods. Av, the month after Tammuz, is presided over in Babylon by Gilgamesh himself.

We can tell you, though, from growing up Orthodox, that these connections were, shall we say, not emphasized. The story, again, was of the emergence of difference: Jewish culture presented as something that had emerged entirely self contained, sui generis, unique, and ex nihilo, out of nowhere. The proof of this was in the story of how it had emerged, here, as you see, sui generis, ex nihilo …

And yet all along the Bible — like the Iliad, like Gilgamesh, like virtually all cultural products — is a remix, combining older forms and ingredients of older stories boiled down in a great trans-cultural stock-pot packed with the inherited cultural wealth of the Near East. That isn't to denigrate these works — it is, in fact, the imaginative, artful fusion that makes them excellent.

But that story of fusion, however true or satisfying, is often politically inconvenient. When a nation steps onto the world stage, Clarke says — like the Athenians in the 4th Century BCE or the Americans in the 1900s — it often becomes necessary for its rulers to justify why, precisely, they are so different from their neighbors. Which is also to say, why they should get to rule those neighbors.

And so, starting with the rise of Athens after its victory in the Persian Wars, a narrative began in what would become the seed of the West. That the East (with which Athens contested for power) was different: sensuous, mystical, irrational. With its cultural canon, Athens laid the first ring of a wall that would survive thousands of years longer than its walled cities or wooden fleets: a political border encoded in literature.

Then, as we'll see, future empires added to the wall. The centuries-long war between the feudal lords of Christendom and the Ottoman Turks enshrined the myth of a Muslim East opposed to a Christian West — even though, as Asher will show, the Turks were more a multiethnic, multi-religious confederacy on the line of the Romans. And the imperial land grabs that followed the collapse of the Ottoman Empire — and the chaos they spread in once quiet countryside — gave grist to another myth. That the Middle East is different. Violent. Irrational. Other.

And yet all along, there has been one story, which is many stories: the true story, that the border is a place of meeting as much as it is one of division. That the frontier is not incidental to culture — that, rather, the frontier makes culture. That the story of simple, coherent, variegated nation-states is, and has always, been, a dangerous fiction.

More Heat Death below the jump.

THE EMPIRE IS A PREDATORY FOREST

The borderlands caught Asher's interest this week after he picked up Osman's Dream, a simultaneously breezy and magisterial history — no small trick — of the Ottoman Empire. The opening chapter describes the rough and tumble world of Late Medieval Anatolia, a landscape of rich plains and rugged mountains caught between the slumbering bulk of declining Byzantium and the West Asian courts of the Seljuk Turks.

The arrival of nomadic and fractious Turkish peoples into the landscape, author Caroline Finkel writes, "disrupted the equilibrium of the older states. The administrative hand of the once-great Byzantine and Seljuk-Ilkhanid Empires did not reach with any great authority into the region of uncertainty lying between them…[attracting] adventurers but also people who followed the frontier simply because they had nowhere else to go."

It was a world of nomads and semi-nomads, displaced peasants and villagers, wandering holy men, raiders and slavers, scholars and merchants of many faiths. The long friction between the great powers to east and west had worn away an open space, and in that space peoples mixed and flowed freely from one to the other.

From such landscapes, new empires are often born. And the Ottomans — one among many other Turkish bands in those rough-and-tumble lands — would move from raiding Byzantium in the 1330s to overthrowing it in 1453, swallowing up the old frontier and everything surrounding it, cementing themselves for centuries as a cosmopolitan superpower. This ascent has been described — by European writers, generally — as a Muslim invasion of Christendom, carried forward on the wings of holy war. But Finkel (quoting Nick Lowry's The Nature of the Early Ottoman State) describes it differently: a 'predator confederacy' of Muslim and Christian warriors in search of plunder and slaves, headed by a Turkish dynasty but not wholly defined by it. Indeed, the rapid explosion of Ottoman conquest was fueled by welcoming large numbers of Christians in to provide manpower for the burgeoning state.

The Ottoman empire that emerged was, in many ways, the last true successor to old Rome: a formidable and rapacious multiethnic state, whose administrative and infrastructural structure bloomed on a constant infusion of nutrients from war at the borders. They were as much a European empire as they were a West Asian one: indeed, their sphere of influence fully united the two. It would be accurate to say that they conquered Byzantium and the Seljuk lords of Iraq and the Levant, but it would be equally accurate, perhaps, to say that they were the ultimate union between those two feuding powers, absorbing their lands and knitting them together for centuries, until the roads ran from Hungary to Baghdad, from Wallachia to Cairo, and none who lived could remember a hinterland between them. E pluribus unum.

This struck Asher particularly because of an interesting Twitter thread he'd read earlier that morning about, of all things, trees.

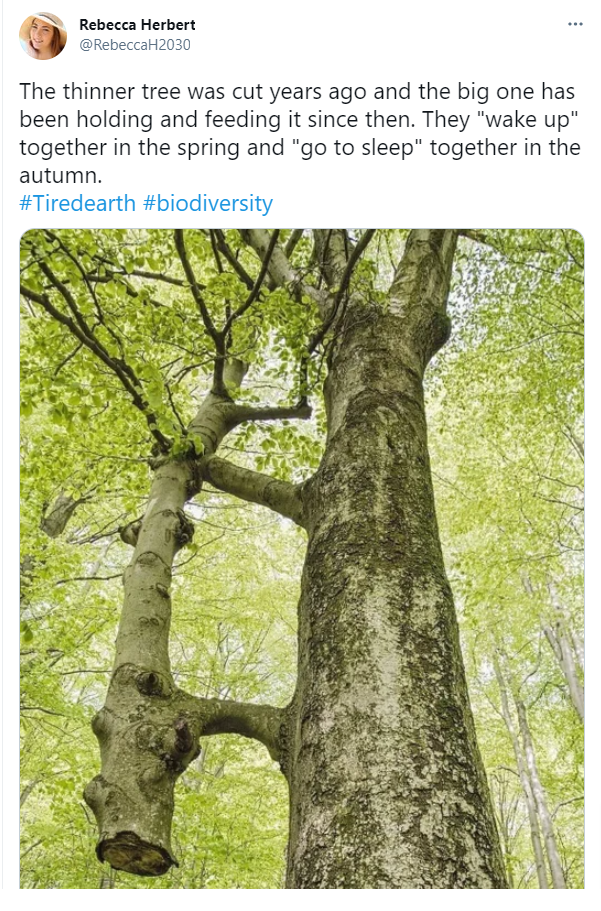

Sometimes trees grow together. It happens in tangled forests and wind-swept groves, where branches rub and clack, their bark eroding to reveal the soft tree-flesh beneath. Their limbs twine until their insides touch and fuse. Nutrients circulate between them freely; they grow together, sleep together in winter and flower together in spring. You might call them 'husband and wife' trees, or 'marriage' trees. You might say that two things which seem separate but connected are — by virtue of that connection — one thing, and it's no longer quite clear where one stops and another begins.

This conjoining—"inosculation" is the technical term—is a natural process. As science writer Ferris Jabr pointed out on Twitter, plants have a remarkable ability to merge with one another, trading sugars and chloroplasts and water and DNA. That natural propensity to react to friction by fusing also makes trees a gift to agriculturalists, as branches from one individual often survive perfectly well — down to the flowers and fruit they produce — when grafted upon the trunk of another. "In Florida, most orange trees have lemon roots," John McPhee writes in his book Oranges. "In California, nearly all lemon trees are grown on orange roots… A single citrus tree can be turned into a carnival, with lemons, limes, grapefruit, tangerines, kumquats and oranges all ripening on its branches at the same time." (Jabr goes into more detail on how this works in a 2012 piece for Scientific American, which is worth a read.)

These are human-created unions, of course, guided by more deliberate actions than the wind that shakes the branches, the slow process of friction, embrace, becoming. But "human-created" is not the same as unnatural. Forests of unrelated species are literally interconnected, bound together by entangled roots and spiderweb networks of fungus. "By analyzing the DNA in root tips and tracing the movement of molecules through underground conduits, [botanist] Suzanne Simard has discovered that fungal threads link nearly every tree in a forest — even trees of different species," Jabr wrote for The New York Times Magazine.

"Carbon, water, nutrients, alarm signals and hormones can pass from tree to tree through these subterranean circuits. Resources tend to flow from the oldest and biggest trees to the youngest and smallest… Seedlings severed from the forest's underground lifelines are much more likely to die than their networked counterparts. And if a tree is on the brink of death, it sometimes bequeaths a substantial share of its carbon to its neighbors."

Plants want to commingle, inasmuch as plants can be said to want anything. Sometimes, at the friction point between the branches of seemingly discrete entities — the place where they rub against each other, the points where they connect — what occurs is not a wound, but a blend. Trees, like empires, wear against one another. Empires, like trees, are never quite so separate from one another as they like to claim. And at the point of contact, sometimes, branches bite so deeply into one another that sap runs like blood between them, and a tree — or state — with two trunks grows up toward the sun.

That's all for Heat Death this week. If you like what we're doing, please feel free to drop us a line at brothers@heatdeath.xyz (And if you've got friends you think would like this, why not invite them to sign up?

Member discussion