Coal Measures

Asher here. Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that knows a format is only there to be broken. We've got something different for paying members today: a 8,500 word sneak preview of the long-threatened book project I'm working on for UT Press. The book is a romp through the history of Texas paleontology – in all senses of the phrase. This chapter is about a period of singular importance in earth's history: the steaming, mysterious jungles of the Carboniferous period, a time when forests reshaped the world, helped birth modern industry, and spurred the organized study of Texas' past.

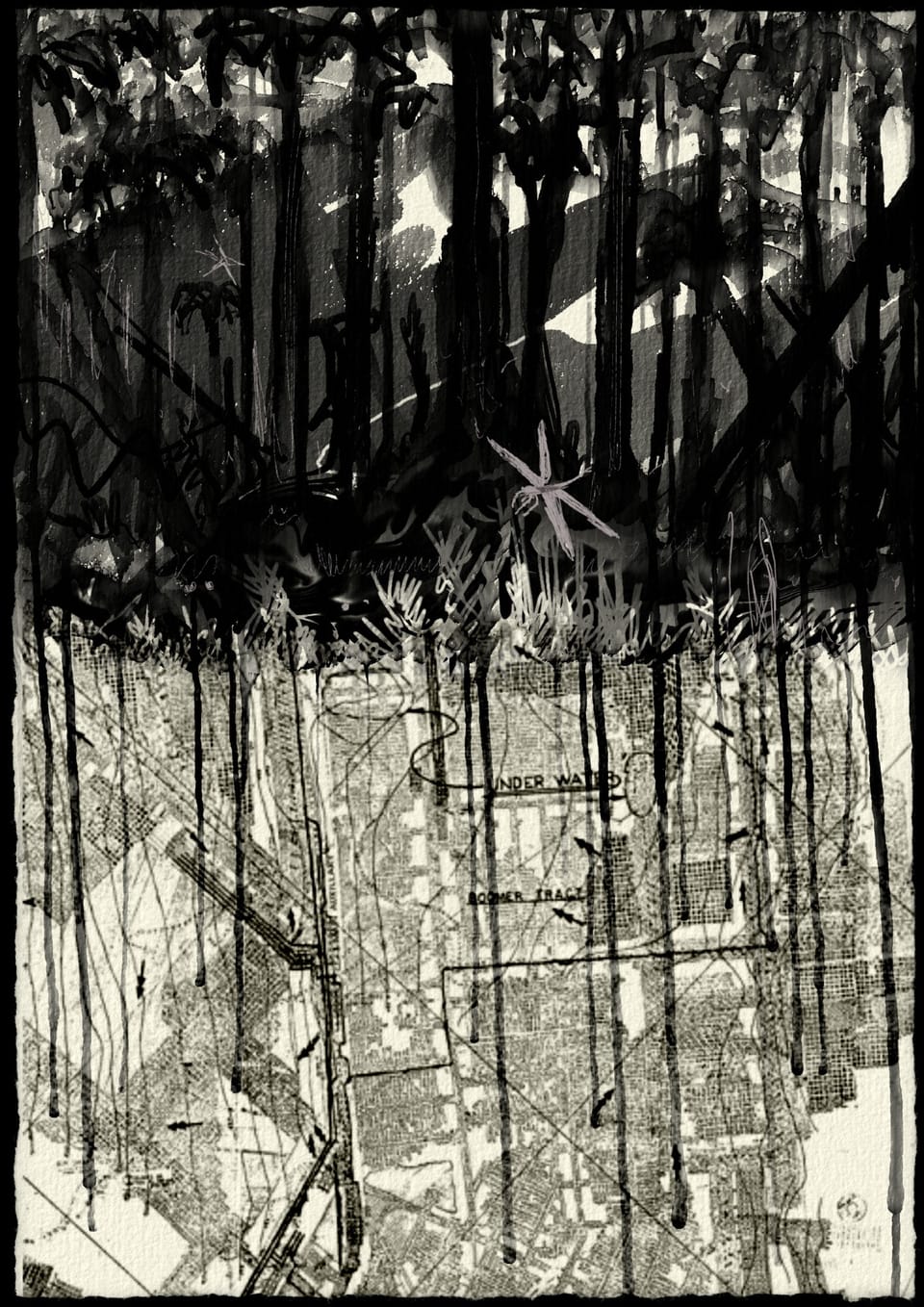

The thing I'm trying to do with this book is to give a sense of the vertiginous gulfs of deep time, make ancient ecosystems come alive, and give a look at both the historical people who helped us understand Texas paleontology and visits to the sites themselves. What I want readers to see is a palimpsest – a piece of paper overwritten many times, with many different stories, all of which are in some ways the same story.

This is not the final draft: the chapter absolutely needs editing, cutting in some places and expansion in others. (I'll certainly be going through and stress-testing facts and conclusions in subsequent drafts. And, of course, there's also copy editing.) But I'm pretty proud of it as a raw piece of writing, and I'm excited to share it.

It's Heat Death. Stay with us.

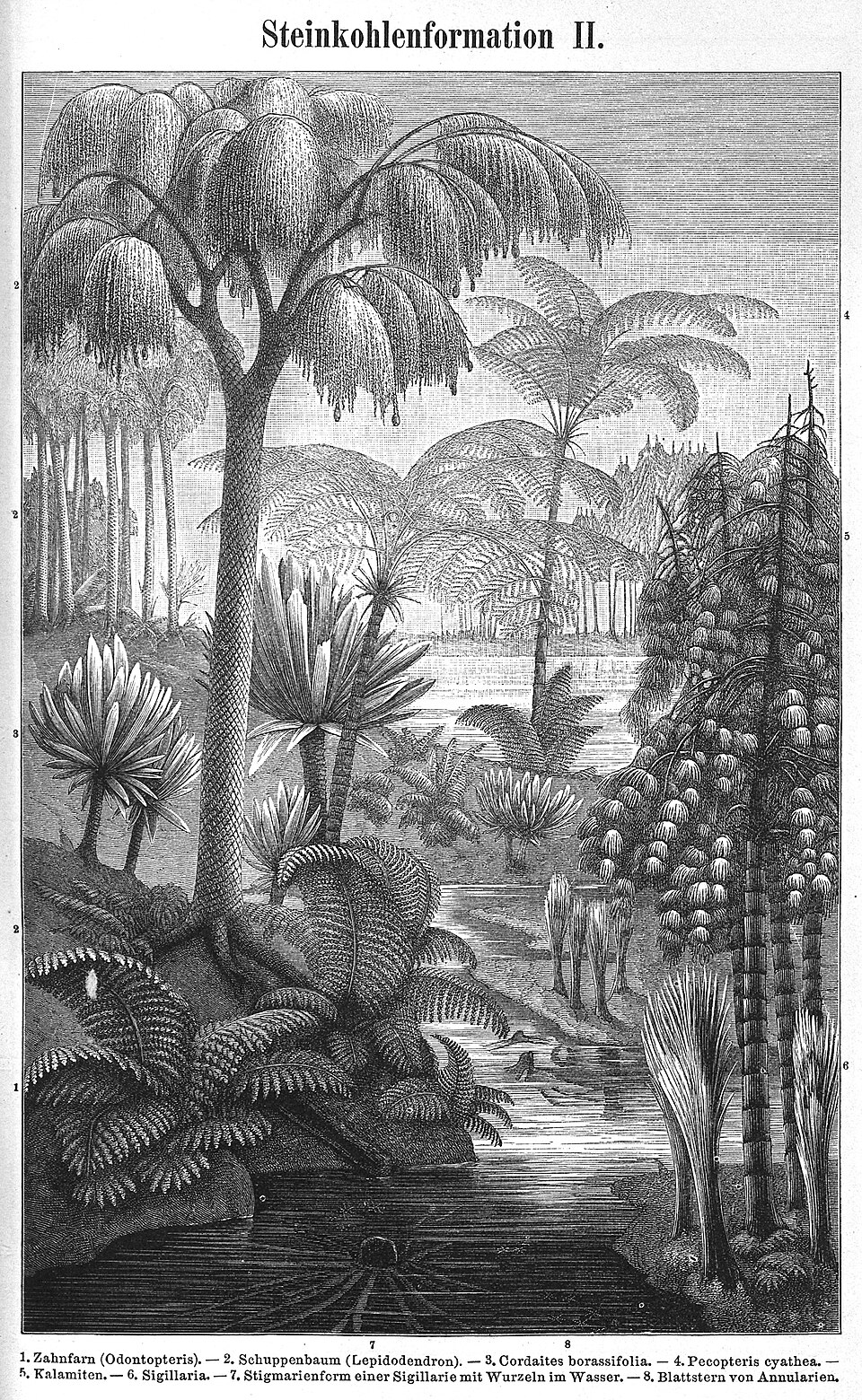

Palo Pinto County, Texas. 312 million years ago. Golden sunlight filters through red skies, gilding the open canopies of the bayou and glinting off the still waters. Explosions of fern and ranks of tall, whispering horsetails glow in the growing light, their stalks and fronds squeezing up and around vast tangles of rotting logs. Great scale trees tower over the wetlands like silent sentinels, their bark marked in rows of diamond-shaped welts, their thin trunks running over 100 feet up into high crowns of delicate, needle-like fronds.

Even at this early hour, it’s oppressively humid. The water table is high enough that every dip and furrow — every hole torn in the soil by the rootball of a collapsing tree — fills with shallow puddles and ponds, the waters tea-brown with the tannins leaching out of waterlogged stems. Black soils are spongy with deep mulches of rotting vegetation, giving off the faint, sulfurous odor of swamp gas. Swarms of dawn mayflies flash and dance over the bayous, scattering and reforming under the diving, buzzing attacks of gossamer-winged griffonflies. It is a world of restless motion, and yet oddly, eerily hushed. There is no dawn chorus of frogs, birds or chirping insects here. Only the rustle of stem and fern, the buzzing hum of gossamer wings, or the sharp splash of toothed jaws breaking the dark waters, striking at unwary fliers.

The tropical forests that grow in these vast coastal swamps are not the tallest jungles that will ever exist, nor the most species rich. But they outrank any other in geological history in terms of family diversity and sheer, sprouting biomass. They are the culmination of a very ancient bargain, one that runs back almost as far as the history of life on Earth.

3.4 billion years ago, strains of bacteria developed the ability to absorb the energy of light — first the dim glow of the geothermal vent and eventually, the blinding power of the sun — and carbon-rich gasses like CO2 to fuel themselves. This process, photosynthesis, made these bacteria incredibly successful, but it had a catch: a toxic gas byproduct called oxygen. As the photosynthetic bacteria spread, the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere grew. Somewhere around 2.4 billion years ago, oxygen levels first reached critical levels, changing the fundamental shape of the atmosphere. While the amount of oxygen would swing wildly over the following millenia, the damage was done. The new atmosphere wrought havoc on the bacterial world, driving the families that could not adapt into dark and secret places: abyssal muds, the black bottoms of swamps, and other places where the corrosive gas could not touch them.

One particular strain of light-drinking bacteria, meanwhile, struck up a partnership with another form of life from a distant and marginal branch of the organism family tree: eukaryotes. Unlike the stripped-down efficiency of bacteria, eukaryotes have relatively complex cells, with thick nuclei and interior membranes holding things like simple organs. They were the sorts of cells you could build a home in, and the bacteria did. They continued to capture solar energy, using it to manufacture organic molecules like sugar for the benefit of the surrounding cell, while maintaining their own lines of DNA. The partnership would give rise to many lines of sun-drinkers; one of them would be plants.

The first-known land plants appeared 433 million years ago, spreading out across a barren landscape previously covered with crusts of bacteria and algal mats. These were the “vascular” plants, which built themselves ever more complex bodies out of inhaled carbon and sunlight: organic pipes that moved water and resources around the plant, with stems to hold them up, leaves to gather the light, and roots to grip the ground. This proliferating ground cover was aided by other bargains, including with early mycorrhizal fungi that helped plants break down and take up nutrients from the rocks. But to be a light-drinker also meant competing not to be left in the shade. Over time, plants grew taller. In doing so, they required tougher and more complex roots, for support and to siphon more nutrients. Over countless generations, these roots broke apart rock, creating the first true soils, and building habitat for the ever greater numbers of terrestrial invertebrates.

By 388 million years ago, the edges of the river estuaries were lined by bunches of early ferns and groves of Wattieza, a tall, thin, palm-like plant growing around twenty feet tall. This was one of the earliest trees, a kind of plant defined not by lineage but by shape: tall-trunked, erupting in branches. With their woodless bodies and simple roots, the earliest trees like Wattieza rapidly hit structural limits on how tall they could grow, and the sorts of habitats they could unlock. Other plants, such as the cyprus-like Archeopteris, soon outstripped them. With buds and branching wooden trunks, these phenomenally successful trees towered up to 80 feet their fernlike leaves drooping in interlocking canopies all across the world. Aided by the development of seeds, which allowed plants to grow in previously inhospitable soils, the great wood marched ever deeper into the dry uplands. When a group of fish living in the warm, oxygen-poor inland swamps began developing lungs and limbs, the forest was there to receive them; had been there, in fact, for a long time.

But these dawn Archeopteris forests — like the ancestors of the chloroplasts dwelling in their leaves — would fundamentally reshape the world. Where the earliest plants could only form thin rinds of soil a few centimeters thick, trees had a more profound impact: everywhere, the powerful roots of the new forests drilled ever deeper into the rock and stone, breaking them apart, mixing the grit with the decaying plant matter to develop deep and nutritious soils, many feet thick. The chemical weathering of the breaking rocks pulled in CO2 from the atmosphere, in an inorganic echo of plant life; so did the plants themselves. As many of those plants died, their carbon was locked away. In the seas, the nutrients unleashed from new soils fueled vast blooms of microbes and algae that pulled still more carbon from the air, and sucked oxygen from the waters as they died, killing marine life. Thick layers of carbon-rich black sludge settled in the basins of shallow oceans, to be covered over by ever more deliveries of sediment.

It did not happen quickly, but it happened. With greenhouse gasses being stolen away, the previously warm climate took a pronounced turn for the chilly. Huge glaciers grew at the poles, pulling down sea levels. The result was a pair of brutal, slow-rolling extinction events, squeezing Earth’s ecosystems in millenia-long vice. The blow fell heaviest on marine organisms; the forests lingered. When the last Archeopteris vanished 323 million years ago, other forms of tree had already largely replaced them — and grew taller still.

Now, the rainforests tower along turbid swamps and coastal deltas of a newly-forming supercontinent. Millions of years ago, the great landmass Laurussia began its slow collision with the southern stretches of Gondwana, forming the great landmass of Pangea. The crunch of tectonic plates created an enormous belt of highlands to the east: the Ouichita Mountains, whose jutting slopes catch the rains that sweep in off the world sea, funneling them back down into the sodden lowlands. There, the sheer weight of the forest — with its complex roots and logjams of fallen wood — chains the rivers, breaking them into braided, nutrient-rich channels that creep between low islands of alluvial soil. The great forests are greedy drinkers of atmospheric carbon, and so at the southern pole, it is an age of ice. At the same time, the sheer masses of photosynthesizing plant life mean that oxygen levels are around 35%, the highest they will ever be in Earth’s history. Between that, the lightning that spears down out of seasonal storms, and forests full of kindling, and it is also an age of wildfire.

But the flames that sometimes sweep over these landscapes are nothing compared to what is cooking beneath it. In the deep mud beneath the tannin-black waters, generations of compressed plants — built from atmospheric carbon and the sun’s energy by their now-dead bacterial partners — are pressed into a soup of leaves and stems, pressed ever downward by occasional infusions of silt and sediment from floods and the pulses of rising seas. In the process, the carbon they bear is locked away in vaults of rock. The heat and pressure of geologic time are creating from them a stone of unusual power, one that will come — much, much later— to define the entire epoch.

A stone that burns.

This has been Heat Death. We're entirely reader-supported independent media. If you'd like to read the rest, please do subscribe: paid memberships are just $2 to $5 a month, and the money goes to support writing like this. (Or you can always leave us a tip!)