Dug Up Treasures

Texas has a long history of fossil collecting. The gentleman scientist (and accomplished feuder) Edward Drinker Cope and his freelance contacts collected quite a few Permian finbacks and amphibians in the the late 1800s. Nascent natural history museums — increasingly taking their modern shape as vertically integrated, philanthropically-funded institutions — made expeditions to the state to cart away fossils. But the state’s most notable paleontological moment, in many ways, came amid the The Great Depression. In 1939, the state managed to spin up a paleontological survey funded by the Works Progress Administration, which put out up to 8 field crews at a time across Texas.

Some of the most famous and iconic fossil sites in the state — the sauropod tracks at Dinosaur Valley State Park, the excavations at Big Bend, in Triassic rocks of North Texas, from the Pleistocene of San Antonio and the Gulf Coast — came from this particular period. America’s looming entry into World War 2 shifted the survey’s focus into the extraction of minerals, but such was the success of the program that pretty much all of the paleontological work done afterward exists partially in its shadow.

Asher here. Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that understands that science is a human – and therefore messy – affair. I’m writing this from within the Vertebrate Paleontology Lab at the University of Texas, where I’ve spent the last few weeks digging into the lab’s archives as part of a book project on the state’s paleontology.

This last week or so, I've been focusing primarily on the WPA era, which has meant immersing myself in correspondence and formal reports, as well the boxes (and boxes, and boxes) of papers of notable Texas paleontologists. I’ve dug through logistical dickering, idle gossip, annoyed corrections; people trying to bargain with each other for specimens, or permits, or access; corresponding with one another over matters of obscure taxonomy or stratigraphy; angling for jobs or recommendation letters, and — toward the end — reaching out to older generations in an effort to record stories of the state’s paleontological past for posterity. I’ve done my best to decipher completely illegible handwriting in field notebooks, and thanked god for the invention of the typewriter. And I’ve made notes of a lot of what I’ve found, which may or may not make it into the final book, but is fun enough that I can’t help wanting to share it.

So consider this, loyal subscribers, a dispatch from the field (even if the field is, in this case, a break room with a fridge whose sign reads – rather intriguingly – FOOD ONLY NO DEAD ANIMALS NO CHEMICALS.) Stay with us.

WPA Blues

The major, federally-funded excavations didn’t last very long — about 31 months — but as I said, they loom extremely large in the state history. “No collecting on a statewide basis had previously been undertaken, and earlier collection had been chiefly by out-of-state institutions,” recalled the program’s director, E.H Sellards, in his final report. “Until recently, one could see a more representative collection of Texas vertebrate fossils in museums in other states and in some foreign countries than at any place in Texas.”

In practice, the way the program seemed to have worked was that the overworked Sellards and the state paleontologist, the affable Glen Evans, oversaw things from Austin, riding out on circuit to visit field crews when necessary but largely leaving superintendents to run the dig crews and keep in touch by mail. A surprising amount of Sellards and Evans’ correspondence is thus dealing with various logistical headaches. Since the rural backroads of Texas were murder on 1930s automobiles, Sellards spends many letters to each crew supervisor troubleshooting car issues — radiator, engine, not enough air in the tires — in tones of visibly mounting frustration.

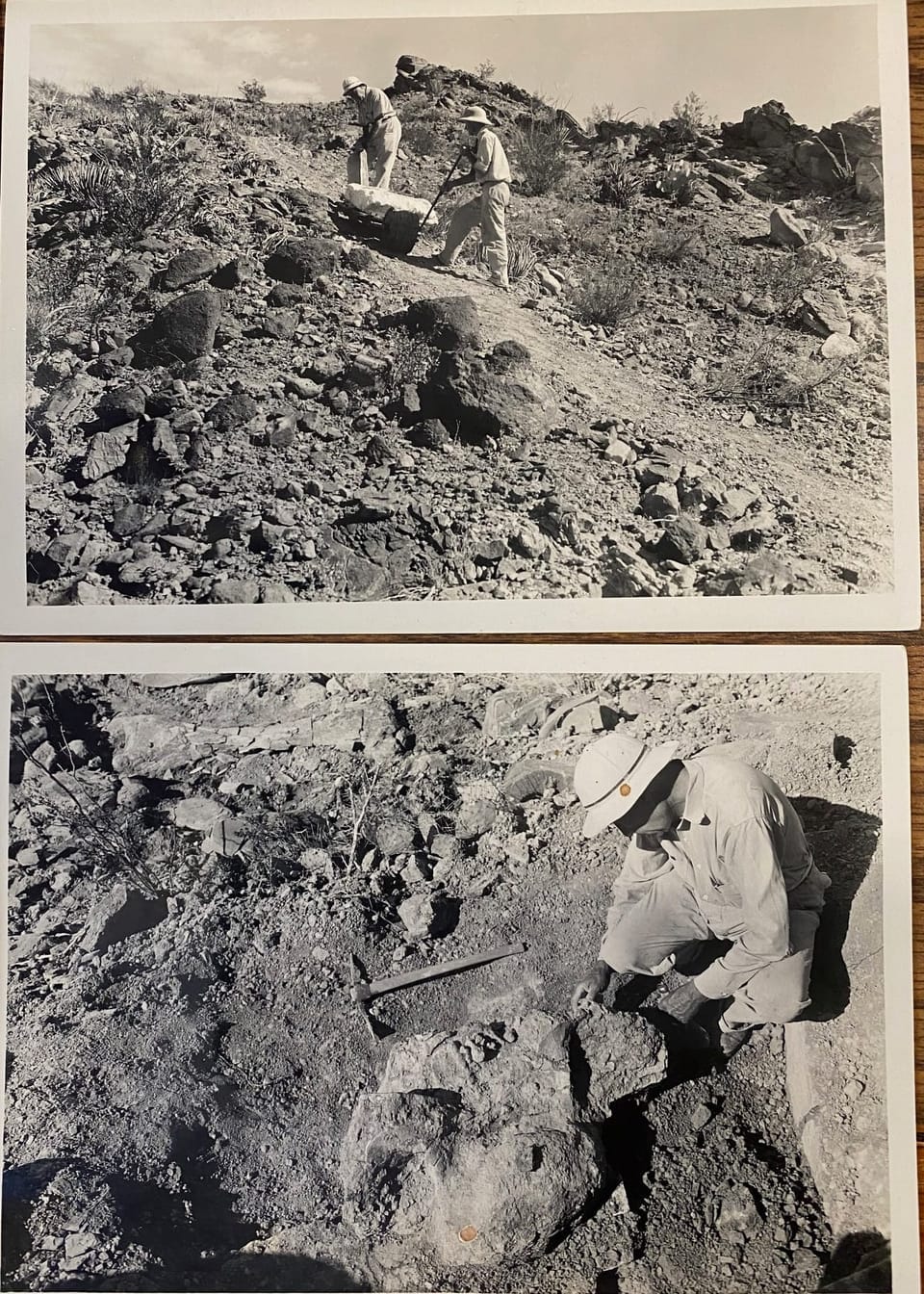

In both his official and unofficial communications, Sellards spoke well of the field crews, the majority of whom — supervisors and laborers alike — were men out of work and without any particular pre-existing interest in paleontology. However, Sellards wrote in one of his formal reports, “the [field units] have made progressive improvements throughout the year. The unit supervisors have become increasingly familiar with the geological conditions in their respective working areas, and some of the workers have displayed a gratifying interest and aptitude for their work.”

This certainly seems to be true, particularly when it comes to the preparation lab set up in Austin to clean and reconstruct the fossils being shipped back, and many of the supervisors observed that — as you’d expect — the field excavators became more adept at the job the more they worked at it. (The best of them, Sellards noted, tended to be those with some mechanical knowledge who were already used to working with their hands.)

Not everyone was so positive. Wann Langston — the mid-century dean of Texas dinosaur studies — came across a WPA excavation in the Big Bend country of West Texas, deep within what is now the National Park. Langston was 17 at the time, and there as part of a competing expedition. He didn’t think much of the WPA crews’ efforts. “It was clear that the personnel were ill equipped to conduct the work they were assigned,” he recalled later. “None of the men had ever seen a fossil bone before, nor had any idea of how to collect fossils. We Oklahomans demonstrated certain collecting methods, showed the foreman how to construct a quarry diagram, and suggested a method for numbering and keeping track of specimens.”

Langston also observed the social dynamics of the dig sight with a somewhat gimlet eye. “The foreman chose from among his charges two individuals, one of whom owned the only truck in the group, and was purported to "have money". This triumvirate was thus somewhat independent of the rest of the crew who had no means of transportation other than the truck that picked them up at the beginning of each pay period and conveyed them to their abodes along the Rio Grande at the end of the period. (In the early days of the project, the round trip for some of the workers was 260 miles). The leadership were heavy drinkers and with their private transportation absented themselves frequently to "go fishing" at San Vicente, on the Rio Grande. There is no evidence, however, that they ever caught a fish, but I was too young to fully grasp the significance of that fact.”

There are some other fairly eyebrow raising things that come through in the letters. “Everything is going forward about the same as usual here,” one superintendent at a dig in Bee County wrote in, noting that the new 130 hour a month schedule was irritating the men, and sharing that he’d fired one man after letting him work three days. ("Ha. Ha.") Then, in an aside: “Jonnie Britt was in a serious accident during the 4th. He wrecked his car and killed a 15 year old girl who was riding with him. Not hurt much himself I hear…”

Another supervisor complained about his field crew in his letters to his bosses. “The general lack of curiosity among my men for anything outside of money and new women gave me an idea last week. I ask them if they ever looked at a magazine called LIFE. One out of ten said that he picked up some magazines in an alley one time when he was collecting junk. They did not impress him. You may wonder why I picked LIFE, or any magazine at all, but I believe it has such a wide range of subjects each week that anyone would find some part of it he likes. As a test, I put two copies, different numbers, in the truck and hauled them around for three days. They were put here and there, held on their laps, placed on the floor of the car. In three days I saw one man glance at the cover of one, turned it over and looked at the advertisement on the back, put it down. How, in the name of something or other, could I ever hope to arouse their curiosity with bones?”

There were bureaucratic headaches, as well. “The timekeeper supervisor of this area has been camping on this job a lot lately and taking up a considerable amount of time,” one supervisor fumed. “With his meddlesome and inquisitive attude, he seems determined to pry into something regardless and get us into trouble. Just why we should be picked on, I can't imagine. He found out that we were leaving town on WPA time and returning on the men's time in the afternoon. When he left, he said that he was going to see that we either left town and returned on WPA time or left and returned on the worker's time. Looks like I am in for something.”

When the field crews did carry out their duties ably and well — which, in fairness to them, they largely did — there was often trouble with landowners, who often had to be begged and cajoled into letting a bunch of fossil roughnecks prospect, camp and dig on their land. “I am unable to tell just how much headway I am making with the Tannheisers, but my hopes are still high and I take every opportunity to be friendly with them, ask them advice about the county, and so forth,” one supervisor wrote in. “The old grandmother, stumbling block number one so far, finally made her appearance in my presence, but did not talk to me. I was thoroughly eyed none the less. A religious motto which said "Prayer changes things" used to hang in one of my aunts house. I failed to ever ask her just what 'change' it made, so have been somewhat afraid to resort to such in this case. before it is over with though, I may try it.”

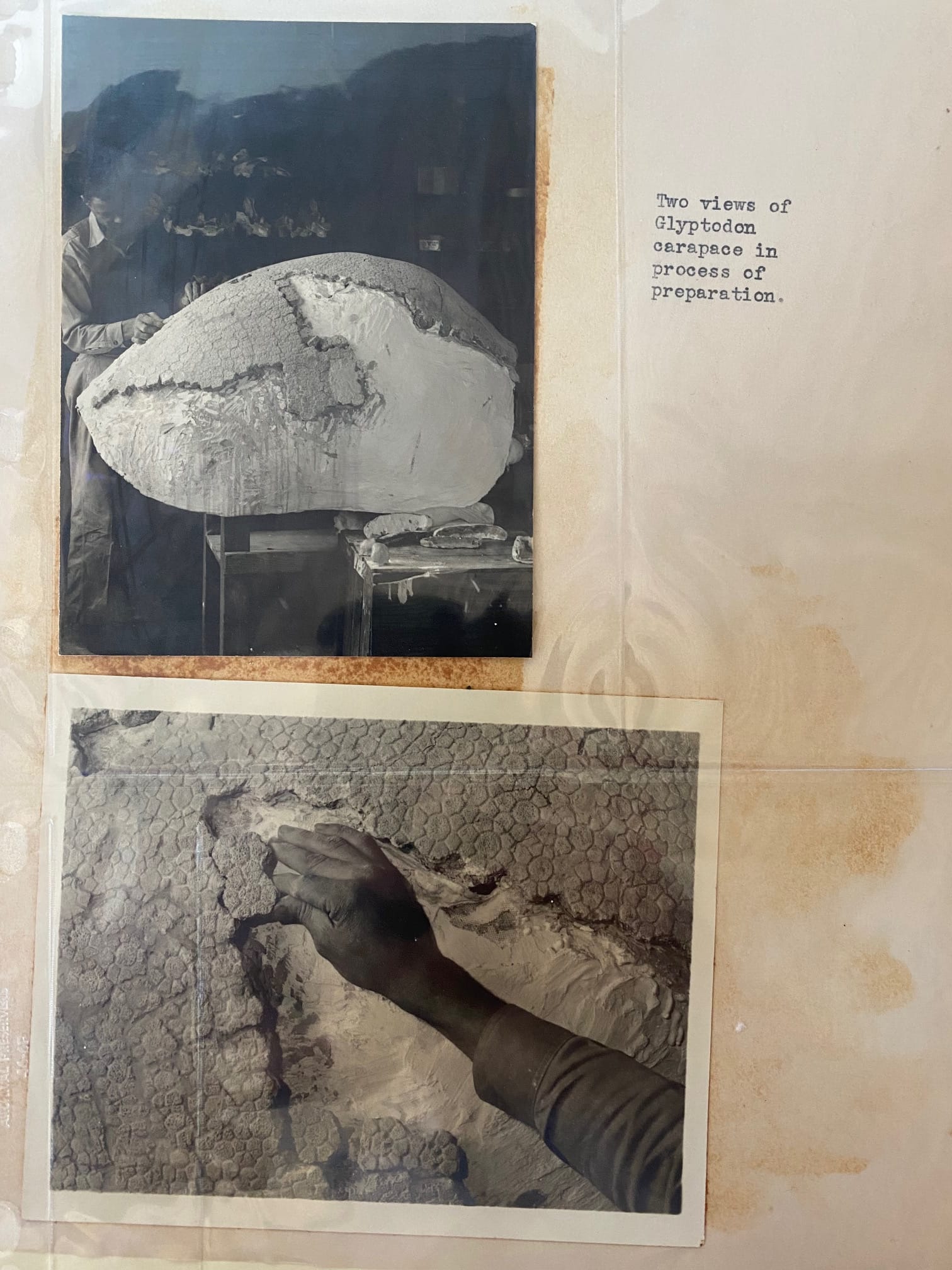

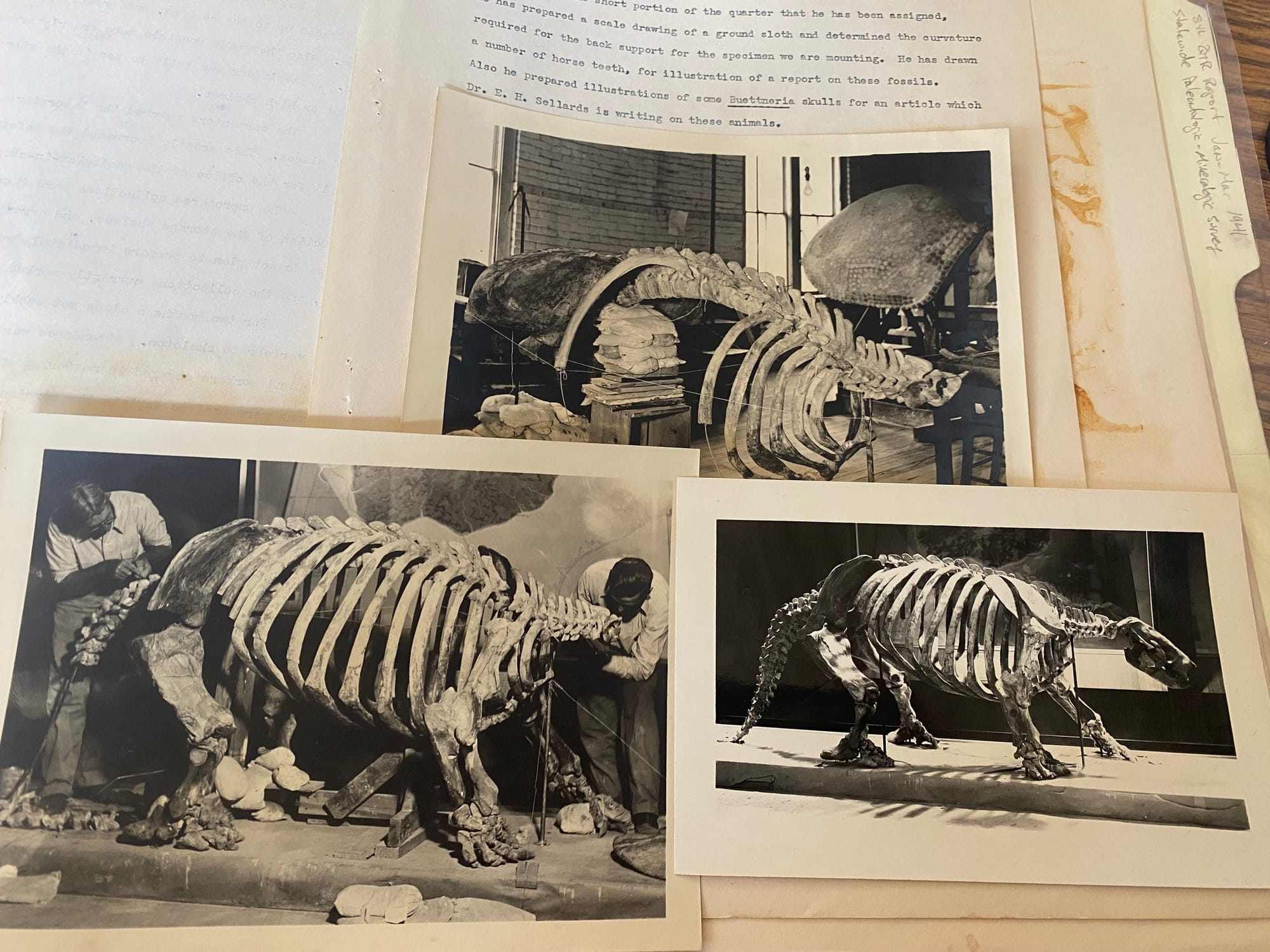

Worse could happen than simply being given the cold shoulder. In 1939, a field crew had been prospecting around the little gulf coast town of Ingleside and had happened upon the Tedford Caliche Pit, an excavation two miles from the sea where workers had quarried calcium carbonate to surface rural roads. The site was the dried remnant of a Pleistocene-era freshwater pond, and turned out to be a motherload for Ice Age fossils: everything from small fauna like frogs and toads to giant, armadillo-like glyptodonts, giant ground sloth, Colombian and American mammoth, cougar, saber cats, dire wolves, camels, bison, tapirs, and horses. Sellards was justifiably over the moon. “The vertebrate fossils which have been collected from the Tedford Pit represents the largest variety of forms, and some of the best preserved specimens” of the entire project, he wrote, calling it one of the most important such sites in the state and possibly the country. He continued to wax poetic about the place — or as poetic as the rather buttoned-up Sellards ever got, anyway — in subsequent quarterly reports.

Then, in summer of 1940, disaster. Abruptly, the landowner seemed to have decided that the 4-5 acre pit would make for an excellent reservoir, and began pumping water from two of the local wells into it. For a little while, the field workers were able to build earthen dikes to keep the rising water out of the low-lying fossil areas, but it rapidly became clear that the Tedford Pit’s days as a fossil site were very numbered. “It is the intention of the landowner to continue pumping water until the entire excavation has been filled,” Sellard’s quarterly report notes gloomily. The ancient pond site was swallowed up by a new one, though admittedly, not before it produced a pretty incredible array of fossils.

Thunder In Their Footsteps

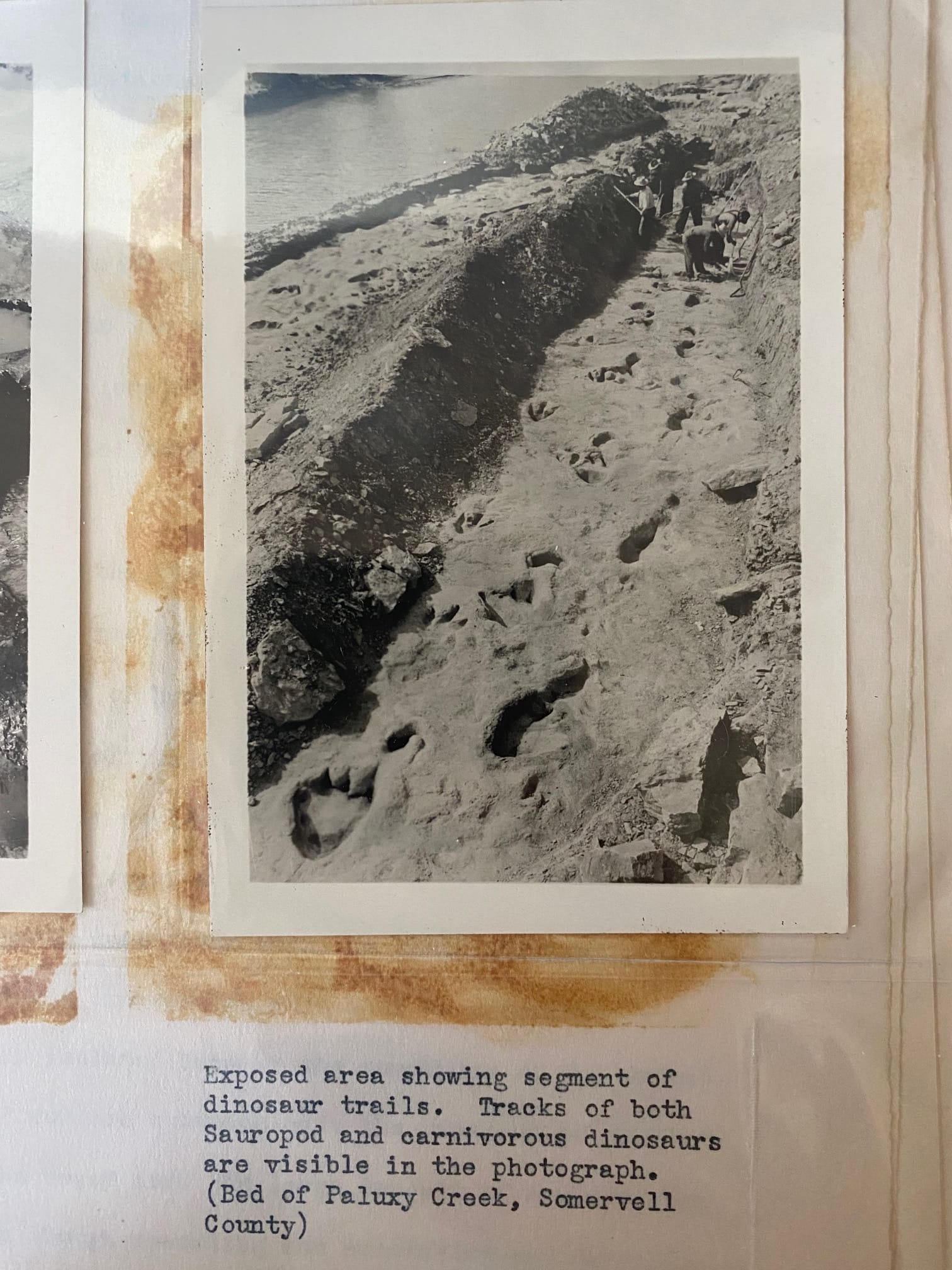

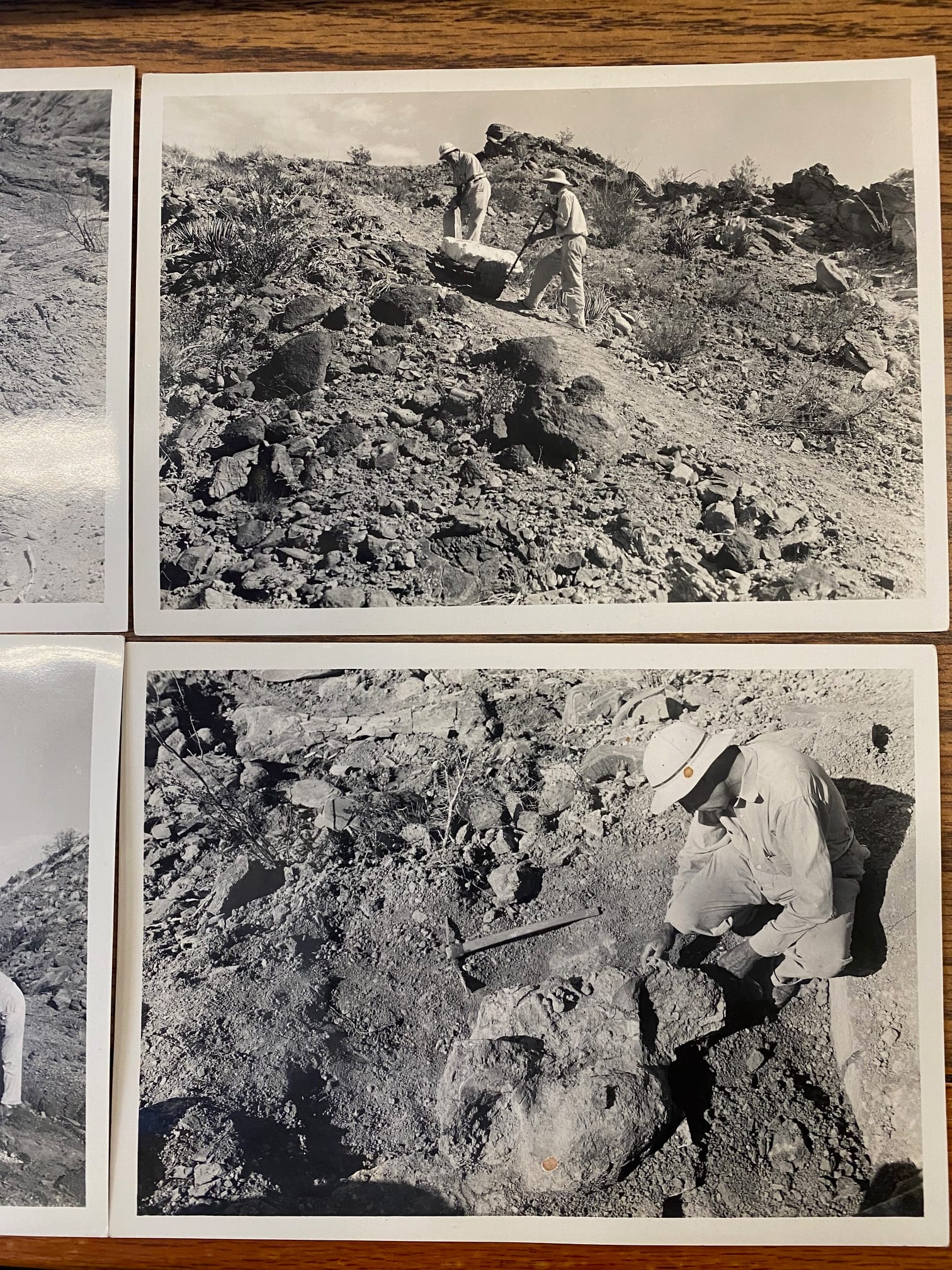

Probably the most famous thing to come out of the WPA projects was the discovery and excavation of Early Cretaceous dinosaur tracks at Glen Rose, a little town about an hour or two south of Dallas, nestled against the bends of the shallow, limestone-bottomed Paluxy river. “There is no doubt now that I have made a very fortunate strike in regard to sauropod footprints here,” wrote in Roland T. Bird, a paleontologist in Texas under the auspices of the American Museum of Natural History. “I hardly dreamed such beautiful trails would be uncovered. It seems to have grown into the footprint opportunity of a lifetime. I only wish that more people could see it while occasion exists.” The excavation — which eventually ended up 210 feet long and 40 feet wide — was clearly a bitch to work on: the WPA men had to dam and divert the river with sandbags and then pump out the water to uncover the tracks, and whenever it rained, the waters of the Paluxy spilled over the sandbags and reflooded the dig site.

What Bird and his workers got for their labors was a beautiful set of long necked and predatory dinosaur tracks, recording well over forty steps in a slab of limestone of around 34 tons.

The excavation, Sellards wrote in a formal report, was carried out with the aim of getting tracks for the AMNH, UT’s own Texas Memorial Museum, and “any other institution willing to bear the crating and transportation expense” which was pretty damn considerable. Somewhat less formally, the letters show a ton of dickering over where various sets of tracks would go. A 28x8 foot slab went to the AMNH to be installed behind its Brontosaurus mount, where it remains today. Another slab went to UT, where it fell on considerably harder times (but is, as I write this, in the process of being renovated at long last.) Denton College and the Smithsonian also appear to have come sniffing after tracks as well, per Sellard’s letters, but not much ever seems to have come of it.

The tracks have had a lot of interesting ramifications for the study of dinosaurs, particularly in trying to figure out how social and active they were. For a long time, the scientific consensus was not very. But in a 1976 letter, the ever-cheery Bird — writing to the grumpy Langston, who seems to have been gathering information about the dinosaur-related WPA excavation — mentioned taking a fresh look at the Glen Rose trackways, as well as others from the area he’d worked on. One inspiration for this was, apparently, that Bird had read an extremely spicy paper by a young scientist, Robert Bakker, called “The Superiority of Dinosaurs,” which argued sharply that dinosaurs were much more evolutionarily complex and interesting than most researchers of the time were giving them credit for. (“I’m conservative,” Langston quips in one of the archived letters. “I don’t like my dinosaurs in a hurry.”)

Bakker, of course, would go on to be one of the most prominent popular paleontologists of the 1990s, a fixture in documentaries, consultant on the first Jurassic Park, parodied (not wholly affectionately) in the second, and author of The Dinosaur Heresies, an influential bit of popular science writing. In this much earlier paper, he argued that one of Bird’s tracksuits — a mélange of different sauropod footprints — represented a true herd, with adults on the outside and smaller animals in the center.

“A possible point I never thought of,” Bird admits in the letter to Langston. The paper is one of the things that inspired him to go back through his track notes, he writes, and he now thinks that one of them — a mixture of predatory dinosaur tracks and sauropod tracks where the predator’s tracks disappear for a few strides — might represent an attempted attack. A set of carnosaur tracks appears to “put a group of sauropods to flight,” with one large individual lagging a bit behind the others. The carnosaur attacks the sauropod, gets a big bite in, and is “yanked out of his tracks for his pains.” Then, after “a second obvious attempt to slow his quarry down, the sauropod breaks free, gains a few yards on the carnosaur, and passes the point where curious tip-of-the-tail scraggles slash the across the trackways.”

If Bakker’s idea of the more active, not-tail dragging dinosaurs stands, he muses, perhaps that’s where the larger sauropod lashed out with its whipping tail to drive the hunter back. It’s an interesting early example of someone whose field days came long before the “Dinosaur Renaissance” starting to engage seriously with its ideas.

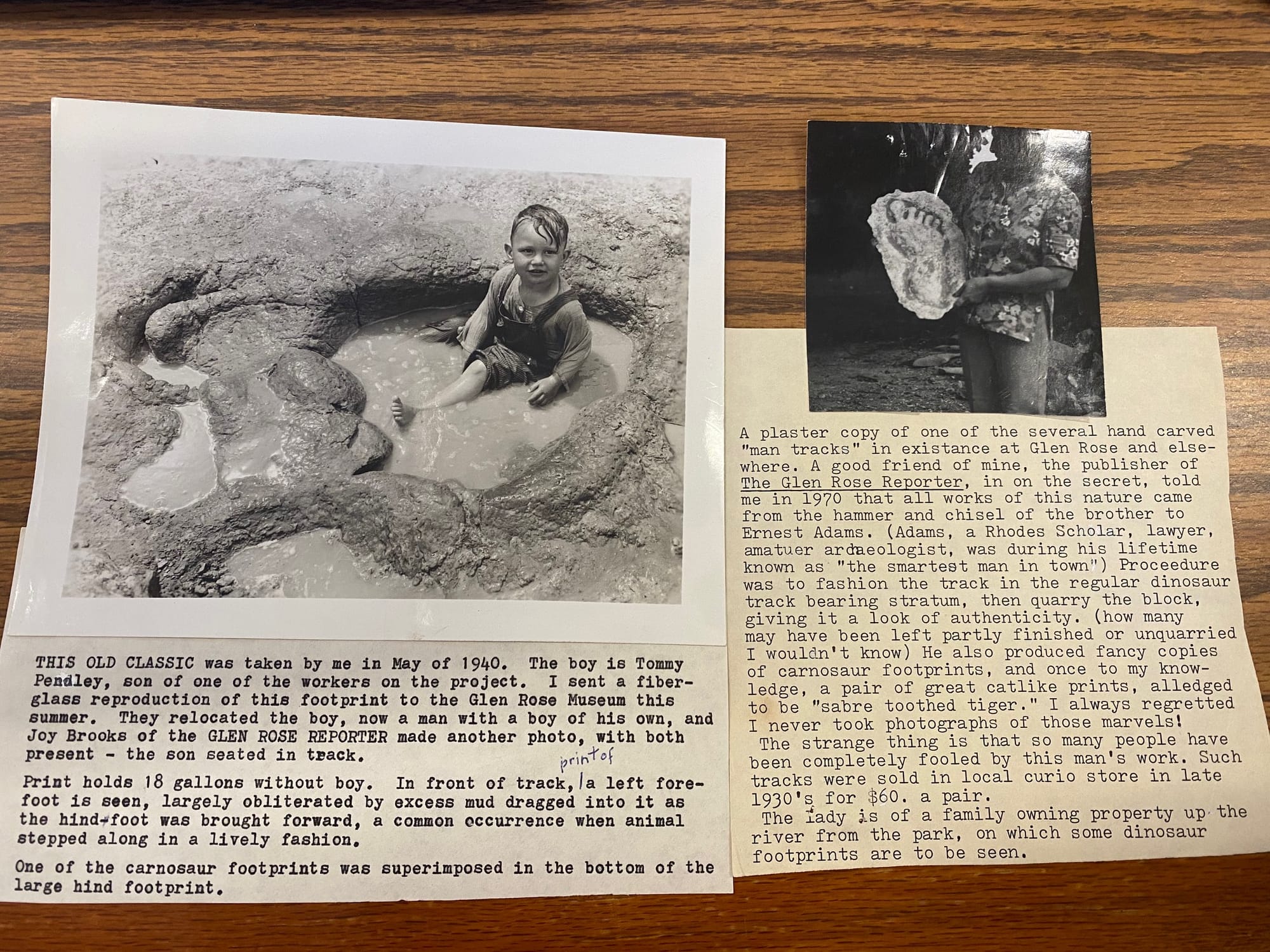

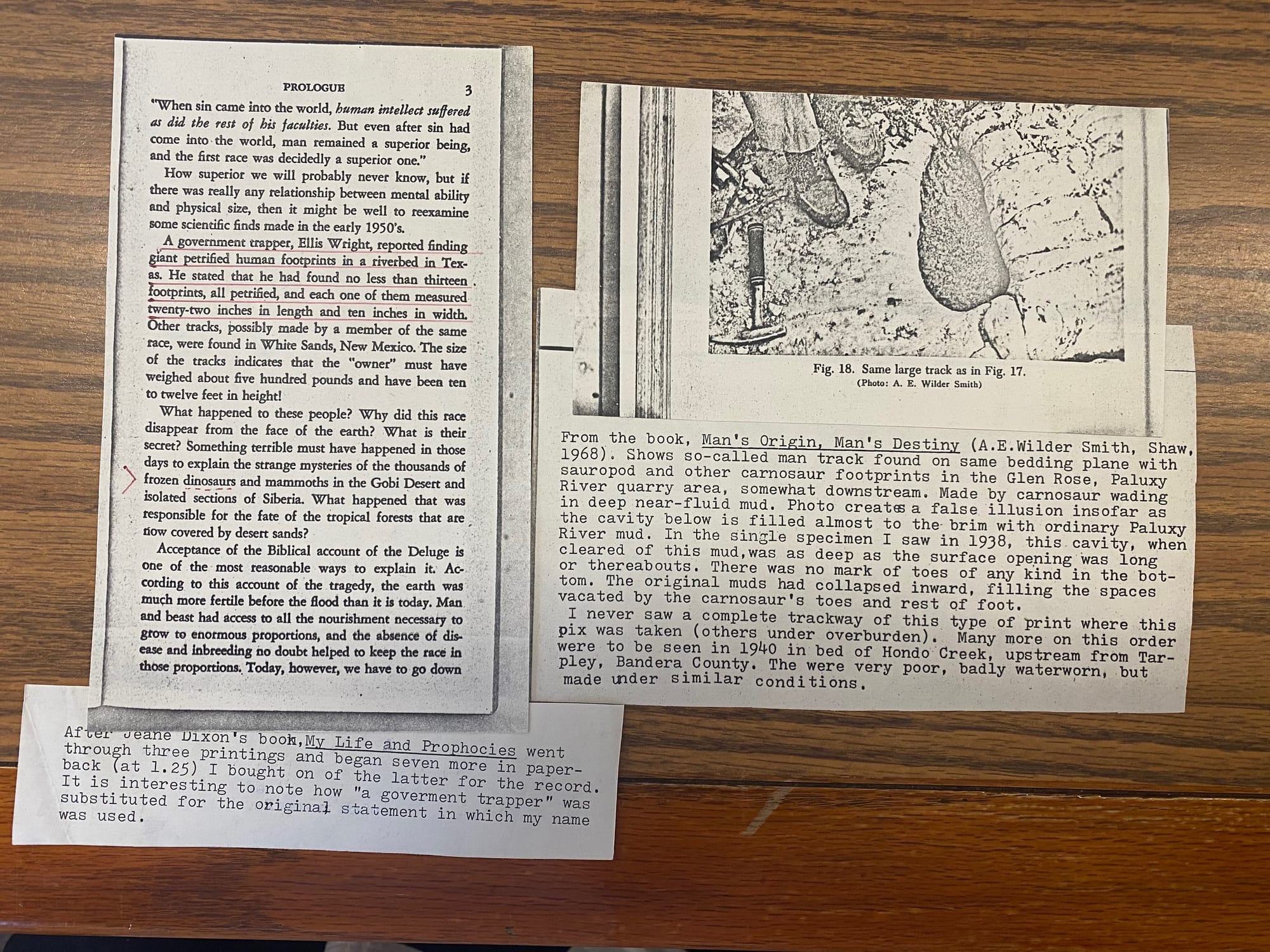

Much more fun, however, is Bird taking a bit of amused responsibility for a perpetual headache faced by mid-century Texas paleontologists (as well as modern ones.) There has been a persistent focus in creationist circles on the idea that “man tracks” are to be found among the dinosaur tracks recorded in the Paluxy, proof that some ancient race of humanity walked with dinosaurs, in supposed accordance with scripture. Langston’s correspondence is absolutely riddled with letters from people across the state asking about it, to which he always responded with polite corrections. Behind the scenes, it seems to have annoyed him considerably. “The alleged man tracks at Glen Rose,” he wrote to Bird, “continue to give me fits.”

“Well, well, well! I can feel for you, for I thought I held a monopoly on that singular affair,” Bird wrote back. “Do you perchance know of some of the allegations that have been heaped on me in the past in regards to this matter? I almost blanch now at the memory!” Most such purported tracks, he observes, are obvious fakes. The “real” ones are pretty clearly what you would get when a large dinosaur — or for that matter, a chicken — wades through thick mud, though they’re enough “to make certain members of the present day human race ready to call you a liar and a cheat if you so much as attempt to tell them that ‘no man lived in the age of reptiles.’”

But the whole thing is sort of his fault, Bird explains. He’s a good storyteller, so I’ll let him tell it from here.

“How did I ever get caught up in these persistent arguments (based on these and other "tracks") that hold that men and dinosaurs existed on earth at the same time together? I made the unfortunate mistake of describing all too well both the fake and the real variety in the first article I turned out for Natural History relating the discovery of the Glen Rose sauropod footprints. But these were the days when both Barnum Brown [the discoverer of T.rex and main paleontological curator at the AMNH] and I were dependant on the Sinclair Oil Refining Company for field work grants. As the company sometimes featured Barnum's planned expeditions in their national advertising, it behooved [us] later to write articles that would please old Harry Sinclair and soften him up for yet another season…Thus the article on the discovery of sauropod footprints at Glen Rose, Thunder in their Footsteps, intended for Sinclair's eyes as much as anybody's, went to press, with me trying to add a touch of mystery by bringing in the "man tracks." Who could dream of what might happen, what did happen!

The first rumble of approaching trouble reached me in a little religious magazine mailed from a friend in California, Signs of the Times. It obviously represented the beliefs of those who accept the story of Creation in Genesis at face value. But the feature article, by one Clifford I. Burdick, was something of a shocker….He had visited my old Glen Rose quarry site, and while reluctantly crediting me for saying, "No man lived back in the Age of Reptiles," he sought to prove by distorted statements I could not deny the man tracks were NOT human.

Well, I didn't like this, naturally. But the small magazine had a limited circulation, and while I didn't hold with its beliefs, if it helped some in their worship of the Almighty, I could stand it. That R.T. Bird (and a "Dr. Bird" no less!) hadn't been able to get around "human" tracks in the early Cretaceous, was to laugh. I only hoped others who knew me would also laugh.

One great flaw in my article in the beginning paragraphs was the unfortunate use of "incredible"" when "impossible" was intended. That was the crack in the dam, and subsequent authors were not loath to use it.

…Perhaps you already know how parties from these religious organizations came to dig for more man tracks at my old quarry site. They wanted proof of their own that such were here, and did not have much trouble establishing that truth when they struck that trackway of a car-nosaur extracting his feet from deep mud with all three toes compressed together for easy withdrawal. The original muds at the area vary widely, from a hard sandy based type that retained poor prints, through those of perfect conditions to this fluid stuff where this one known carnosaur waded.

Following these expeditions there in time emerged a respectable appearing book entitled Man's Origins; Man's Destiny. Eventually a copy came to hand from a friend in Pennsylvania. Much of the book's religious theme was tied to the man tracks, and again I suffered under the old aforementioned allegations. I was by now losing all patience with this "Dr. Bird" thing, and while the author still gave me credit for stating "No man lived back in the Age of Reptiles", he did so reluctantly, going to great lengths to prove I didn't know what I was talking about, and condemning me for never again mentioning the man tracks in subsequent articles. The book was profusely illustrated by photos of sauropod and carnosaur tracks, together with those of the hand carved fakes and the mud wading carnosaur -- both of the latter in his view true footprints of giant men.

Would a day come when an author might drop my one defensive remark altogether? I couldn't believe it, but when the horrifying news came that a book now enjoying national circulation had done just that in the opening prologue, I almost fainted. Who was the author this time?

…I entered our local Homestead library in fear and trembling. Was the book I sought "in" at the moment?

It was. It stood prominently displayed on a shelf of new books where it could not be missed by an incoming patron. All doubts about the author vanished now. Who, indeed, had not heard of Jeane Dixon [who achieved nationwide fame for predicting the assassination of Kennedy in 1963] the current outstanding lady seer, often consulted in greatly publicized circumstances to prophecy the futures of prominent Americans, the outcome of future elections and author of another recent book The Call to Glory. What had this woman wanted of me?

Can you imagine my mental anguish as I read, "Dr. Roland T. Bird of the Department of Vertebrate Paleontology of The American Museum of Natural History reported finding giant petrified human footprints along with those of dinosaurs in a river bed in Texas"? It was appalling to think of how many thousands of homes in America this book was invading at this very moment, from libraries and book stores everywhere.

When I was fit to speak again, I fired off a scathing letter to this female "seer" demanding two things, one an immediate withdrawal of my name from all future reprintings. In turn I received an immediate apology from her ghost writer, and saying my name would never appear again in future editions. There is more to the story I need not go into here.

Well, lawsuits are messy things, so I didn't file suit. Time soothes the most painful of injuries, and again in this case, I was mollified by the usual religious overtones of the book. If her story should help bring some of her devoted followers back onto the paths of righteousness and the good will all of us should practice toward our fellows in this world here below, I would overlook the insult.

As for those persons in vertebrate paleontology who might happen to see this book, I could hear them chuckling and saying to eạch other, ‘Well, well, well, old R.I.Bird seems to have got himself into a jam here. The woman has, of course, grossly misquoted him. There must have been some flaw in his original story. How did that escape old Barnum Brown? He and Bird always worked closely together.’”

A lesson to all of us working in science communication, there — be wary of punching up a finding.

Wartime

By early 1941, it was fairly clear that the paleontology side of the project was entering its last days. The war in Europe was exerting an increasingly gravitational pull, and though the US would not formally enter it until the Pearl Harbor attack in December, the government’s interest in geology was taking a marked turn for practical extraction, mostly minerals. The Texas Paleontological and Mineralogical Survey dropped the “Paleontological,” and all subsequent work was focused on scouting out mineral outcrops for the coming war.

In his final report, Sellards — rather touchingly — noted that “it will be necessary to look to the future following the close of the present World War” to complete the study of the fossils. Honestly, it hasn’t yet been accomplished: while much of the material was prepped, mounted and studied, quite a few plaster field jackets from the WPA days remain unopened in the basement of Austin’s Vertebrate Paleontology Lab.

One fun epilogue to this can be found in Bird’s letters to Langston. In 1940, he and Barnum Brown had spent a while prospecting in the Big Bend country — somewhat to the annoyance of the officials for the park, which was in the process of forming — and collecting a ton of fragmentary but interesting cretaceous material, including the first good remains of the giant dinosaur-eating croc Deinosuchus. It was to be the rather elderly Barnum’s last ever dinosaur collecting expedition, and Bird’s last such in Texas.

With the outbreak of the war, Bird writes, Barnum “disappeared” up to Washington, where he did some rather nebulous work for the Office of Strategic Services and the Bureau of Economic Warfare. (In an entertaining biography of Barnum Brown which discusses some of his many peccadillos, Brown’s daughter came to be concerned that her skirt-chasing father was in the process of being honey-trapped by a Nazi spy, though what she could have wanted with him, precisely, isn’t clear.)

Bird, meanwhile, got recruited as a geologist for an undercover project. After “virtually sign[ing] my life to secrecy,” he and his colleagues were tasked with mapping the Jurassic strata of the Morrison formation, particularly the uranium rich areas around Wyoming and Colorado. “The uranium was needed for possible use in the atomic fission field, as an untapped[sic] source of energy, the use of which I might well guess,” he wrote to Langston in 1976. “They said time was of great essence if the project (sponsored by the US government) could get ahead of the Germans who knew as much regarding the radioactive properties of the metal as we did.”

How much did Bird know about the purposes of the Manhattan Project? Probably not much: he seems to have learned what all of that was actually for when the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A few weeks after that, he tried to write an article for Natural History about how he spent the war looking for Jurassic dinosaurs and mammals as well as uranium. When the editor sent it to Washington for clearance, he recalled, “did they raise a yell! They didn’t give a whoop about fossils but who was I to break a secret trust! The article of course never saw print.”

So far as I can tell, this may – may – be the first time that detail has been reported publicly about Bird. He didn't mention it in his book (the very lively Bones for Barnum Brown) and it's gone unremarked on in academic sources.

A good reminder that you never can tell what you can find in the archives – and the field isn't the only place to dig things up.

That's Heat Death, everybody. We'll be back soon with more interviews and musings on past, future, and all the crises in between. If you enjoy our work, don't forget to subscribe!

Member discussion