How (Not) To Domesticate A Cassowary

This is the cassowary, in brief: A helmeted, gimlet-eyed head. A hulking 130 pound body, covered in shaggy, funereal feathers. Two powerfully muscled legs, tipped with four inch, velociraptor-like talons.

In April of 1926, two young teenagers—the 16-year-old Phillip McClean and his 13-year old brother—came across a cassowary on their property. They set upon the bird with clubs, and soon found that they had picked a fight entirely beyond their capacity. By then it was too late. The cassowary came after them; Phillip McClean tripped while running. The cassowary lashed out with one powerful foot and cut his throat, and he bled out there, pumping his life out on the jungle floor.

As it happens, the next recorded fatality-by-cassowary took place on April 2019, in Florida. An elderly exotic animal owner, Marvin Hajos, tripped and fell by the fence of his cassowaries enclosure. He received a rain of kicks through the fence, mortally wounding him: he died hours later.

It’s possible that neither individual quite understood what they were dealing with. But then, they didn’t have thousands of years worth of experience with cassowaries to fall back on. And they could never have guessed just how adeptly some peoples have managed the world’s most formidable bird.

Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that asks whether “murderbirds” are actually “justifiable homicide birds.” As September ends, the Elbein Brothers are closing out an enjoyable month of proximity by once again going their separate ways. Saul’s drive back to the DC Soviet (soon, happily, to become the Austin Soviet) means that he’ll be out of pocket for this week, resulting in a fully Asher-run newsletter.

Not to worry! We’ll be returning to the world of science and natural history this week, with a deep dive into Asher’s recent New York Times piece on the deep history of humans and cassowaries. Discussions will include talons, the difficult mechanics of domestication vs. management, indigenous knowledge, and what an eggshell can tell you. (It turns out to be a lot.)

It’s Heat Death. Stay with us.

The Deep History of the Cassowary

Asher here. Southern cassowaries are—as we have seen—very formidable birds. Which makes it all the more surprising that they may be the earliest known example of a bird humans have tried to raise.

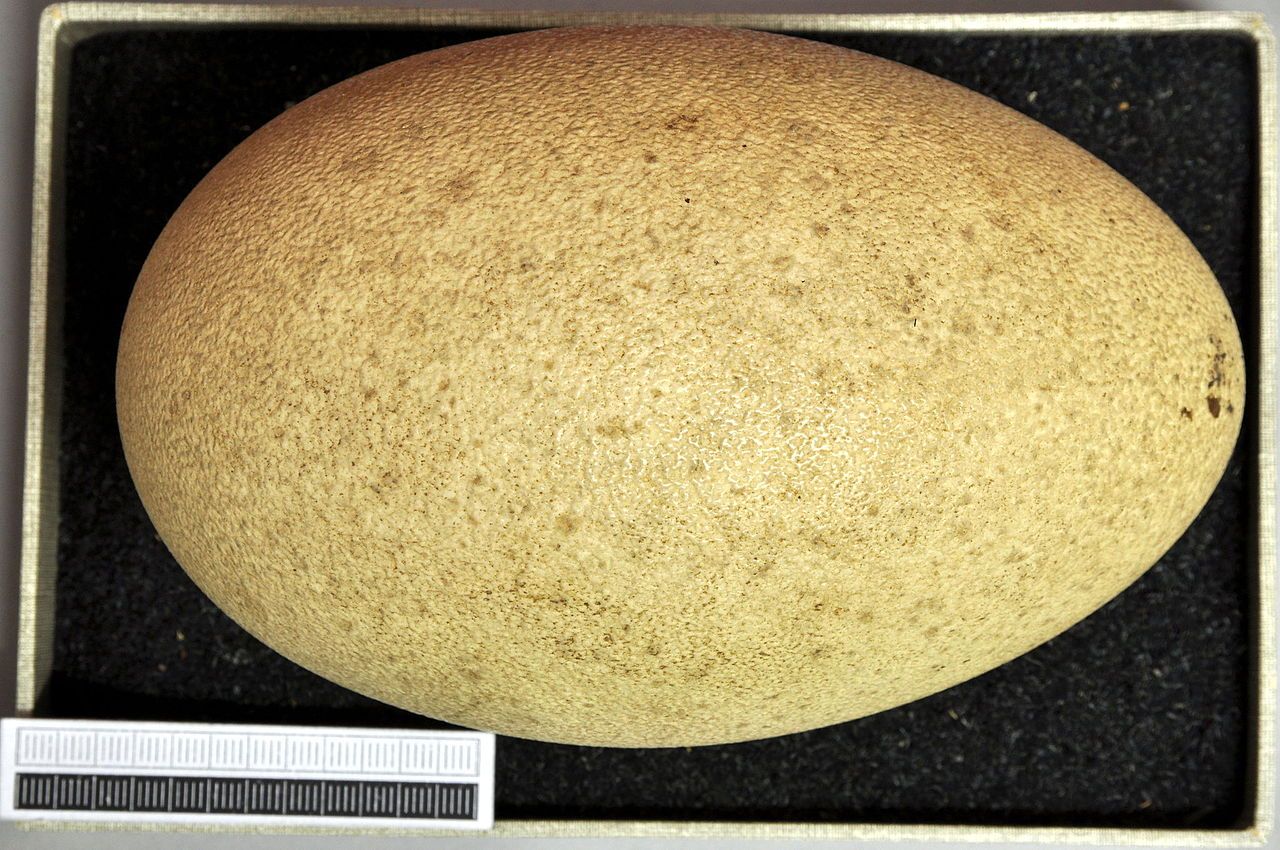

A new paper in the journal PNAS uses a eggshells to argue that people in Late Pleistocene New Guinea harvested cassowary eggs, possibly to hatch and rear them. They seem to have begun doing this as early as 18,000 years ago—thousands of years before the first known domestication of ducks and chickens. (I wrote about it for the New York Times,in a piece that includes some absolutely jaw dropping photography.)

It was tough fitting in everything—and my interview with Dr. Kristina Douglas, the lead author on the study, covered a lot of interesting material. Here are some of the things I learned from talking with her.

True Facts About the Southern Cassowary

Ranging from the forests of northern Australia to the dripping highlands of New Guinea, cassowaries are an important keystone species, devouring fallen fruit and thus moving seeds up to a kilometre around the forest. Some rainforest trees apparently require passage through a cassowary’s gut to germinate: it might be fairly said that their bellies are a primary current by which the trees flow through the jungle. (They’ll also take the occasional lizard, bit of fungi, or grass stem as well: like all flightless birds, their first instinct is to peck at anything they find interesting.)

They are, in contrast to their fearsome reputation, quite shy, though they can be territorial and jumpy. One study of 221 cassowary attacks found that 109 of them happened because the cassowary had learned to expect food from humans, and had lost all sense of wisdom and decorum as a result. Most people injured by cassowaries come away with puncture wounds, lacerations and bone fractures. Cassowaries also attack dogs without apparent provocation, since dingos and other feral dogs are one of their natural predators.

Like many ratites, the males take care of the young. Cassowary females lay multiple different clutches in the territories of various males, before heading off.

The Archeology Of An Eggshell

Douglass and her colleagues’ research focussed on material collected in 1959 and 1960, from a pair of rock shelters in New Guinea’s dripping highland jungles. Plenty of artifacts and remains come from both sites, ranging in age from around 18,000-6,000 years ago, a jaw-dropping span of time. (Recall that just 1,000 years ago, the Eastern Roman Empire was still going strong, and the Mayan polities of Chichen Itza were, to use an archeological term, going through it.)

Among the remains were over a thousand different fragments of cassowary eggshells. Now, eggshell is a really handy thing to find in an archeological deposit, Dr. Douglass said. Obviously, it gives you clues about what people ate, and when. (Migratory bird remains are particularly helpful here, since they tend to show up in specific places at specific times of year.) The isotopes in eggshell can tell you a lot about changes in climate, which has a huge impact on human societies, as we are all discovering to our great dismay.

Shells can also provide evidence of symbolic and cultural expressions, too. “Eggshell is one of the materials that goes back to our earliest days as a modern species: we see people using ostrich eggs potentially as drinking vessels, and not too long after that, people making beads out of ostrich eggshell,” Douglass said. And if you can tell when an egg hatched, the amount of information you can pull out is even higher.

So How Do You Know When An Egg Hatched?

The principle is simple. As a bird embryo develops inside an egg, it draws nutrients from the surrounding eggshell to build its body. As the chick inside gets larger, the inside of the shell gets thinner—and the process creates a predictable pattern of erosion. If you can crack that pattern, in other words, then you can tell how far along an egg was by how the inside of the shell looks.

Douglass and her colleagues worked out a technique using a huge collection of ostrich eggs. “We basically have multiple eggs sampled for every day of incubation and development. For ostrich, that's 42 days,” Douglass said. “So that’s a large sample!” From there, they used a mix of statistical modeling and “visual analysis” — informed eyeballing — to predict the age of an embryo based on the pattern inside the shell.

The implications of that are actually really useful: if you’re finding eggshell fragments from early in an egg’s incubation period, you can surmise that people are either eating yolk (like you do at breakfast) or making use of the shell for cups/jewelry/etc. If you’re finding shells from late in the process, people might be eating a fully developed embryo, which is a delicacy in some cultures. Alternately, there’s a good chance that they’re allowing the egg to hatch, and raising what comes out.

By comparing the 18,000-6,000 year old cassowary eggs fragments to ostrich shells, therefore, Douglass’ team could get a pretty solid idea of roughly how developed the embryos were. It turns out that a significant chunk of them came from eggs very late in development. Possibly they were eating the fully formed embryos, Douglass says. But it seems likely that the ancient people of New Guinea allowing them to hatch.

The Vanished

The cassowary wasn’t the only flightless island bird that modern humans encountered when they ebbed out of Africa in the Pleistocene. Humans settling on Madagascar 11,000 years ago encountered elephant birds like Aepyornis, some of the largest birds ever to exist. And the arrival of the Maori people in New Zealand in the 13th century intersected—perhaps terminally—with the moa. Either way, both were extinct by the late 1400s.

Hunting usually gets blamed for this, and that idea actually prompted Douglass’ wider research study. In her grad student days, Douglass was digging around southwestern Madagascar, looking for signs of extinct animals like Aepyornis. If the birds were hunted to extinction, that should have left a bunch of butchered remains. She didn’t find any. But eggshells were everywhere in her archeological sites, sometimes blanketing the ground.

So were people collecting Aepyornis eggs? That remains to be seen, Douglass says. But the first Malagasy peoples were foragers, and seem to have gotten along with elephant bird populations without much trouble. The problem came 1,000 years ago, with introduction of pastoral land management practices: cattle, sheep, goats, and dogs. That, combined with climatic fluctuations, seems to have driven Aepyornis and the island’s other megafauna to extinction. (Too often, domesticated animals end up displacing wild competitors.)

What about Moa? The research isn’t complete there, either. “But what seems to be happening is that the birds and their eggs are being consumed in these large feasting events,” Douglass said. “I expect we’ll find that eggs were harvested as people find them for these large ceremonies.” Not, in other words, selectively, as seemingly occurred with cassowaries.

Why Hatch A Cassowary?

So why would someone hatch a cassowary out, anyway? As it happens, the rearing of cassowary chicks happens on New Guinea today. Certain peoples on the island regard them with reverence and respect, as befits a large, dangerous animal on the landscape. The Maring people of Kundagai have a tradition of ritually sacrificing cassowaries; other societies considered them not birds, but kin. The meat and feathers are highly prized among some highland societies, including for ceremonial gift exchanges.

One way to ensure that you have birds for this purpose is to make sure there are reasonably tractable ones hanging around. “It makes a lot of sense if you're thinking about cassowary being a really high value resource, valued for subsistence, ritual and trade,” Douglass said. “But they're incredibly difficult to hunt and capture alive. And if you’re trying to move that resource around in a highly mobile society, it can be hard to do that. Having the ability to harvest eggs and then have chicks imprint on you would make that a lot easier.”