Hunting Men: A Conversation with Gretchen Felker-Martin

A key element of oppression and civil conflict of all kinds is the curious way that those who have power over other people convince themselves that they are, in fact, the ones under a monstrous threat.

The disenfranchised Black family in 1950s Mississippi; the Jewish or Roma family in 1930s Berlin; the Syrians smuggling themselves into Fortress Europe or the Central American migrants working their way towards the U.S. border in 2021 — all of these people can easily be constructed by those who hold the power of life and death over their heads as The True Threat, a creeping zombie menace to society itself, against whom any means may be deployed in the name of protecting civilization or Our Way of Life.

Or as HBO's Station Eleven puts it: "To the monsters, we're the monsters."

Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter where the monster is always somebody else. Today we have something a little different: a searching interview with Gretchen Felker-Martin, one of horror's sharpest and most incisive voices. While she made her name online as a film critic—and one of the best voices writing about Game of Thrones—she’s also a fiction writer, whose self-published horror novels are intense, visceral and deeply, brutally emotional.

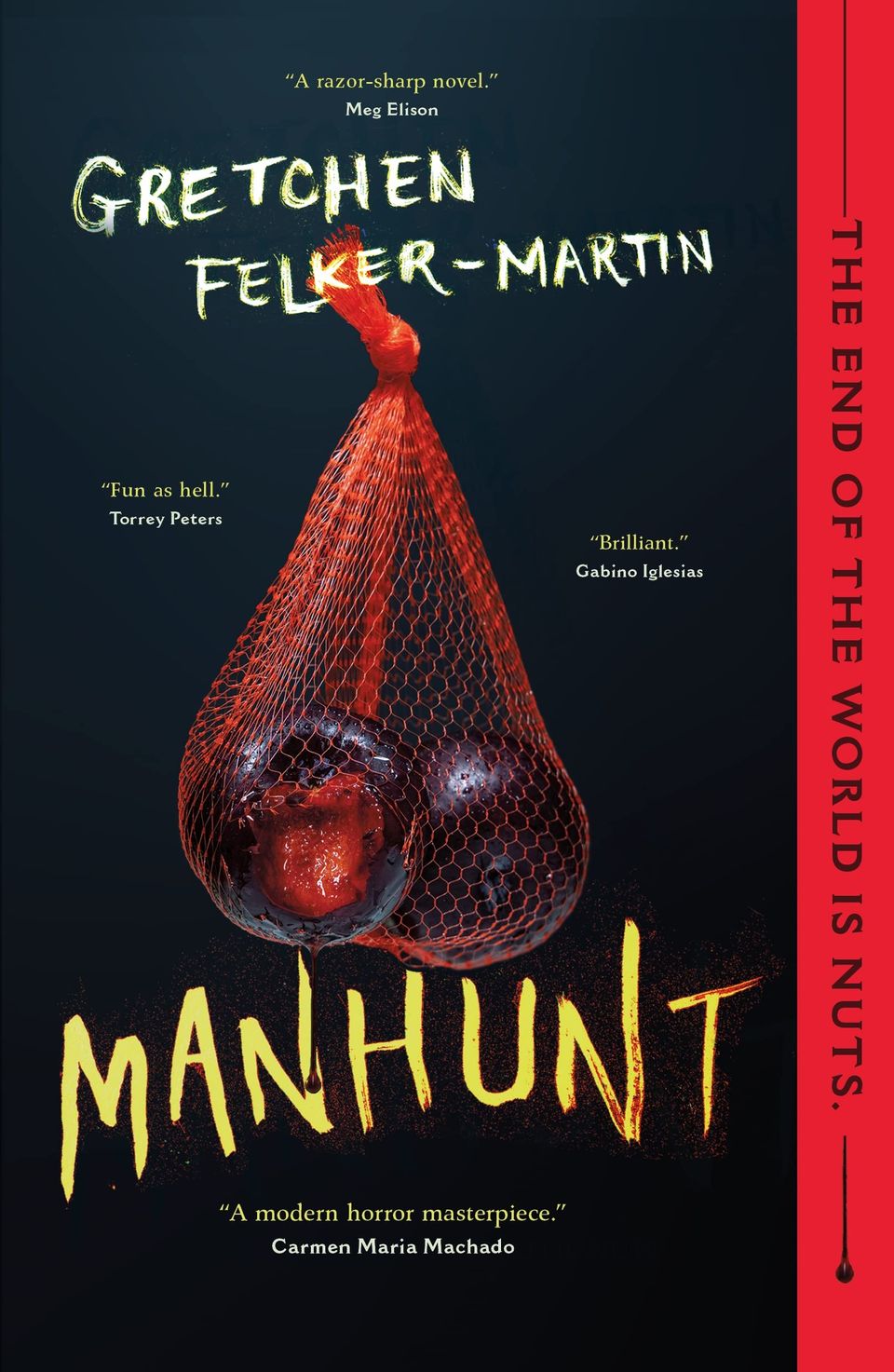

Her new novel Manhunt, which has been picked up by Tor books for an upcoming February 22 release, has been attracting a ton of critical attention for both its killer premise and grippingly sharp, taut prose.

The novel follows Beth and Fran, two New England trans women who spend their post-apocalypse hunting feral men and harvesting their organs in a gruesome effort to ensure they’ll never face the same fate. A brutal accident lands them in the company of the gun-toting, taciturn Robbie, and sends the three hurtling onto the open road—pursued by a cult of fascist transphobes, a sociopathic billionaire bunker brat, packs of feral men, and (of course) their own emotional demons.

Manhunt is mean. It’s sly. And it’s as deeply tender as novel about trans women harvesting zombie men’s balls can be. Asher caught up with Gretchen to talk about the origins of her novel, gender apocalypse stories, the importance of sexuality in media, and how to reject the very notion of safety. The conversation has been edited for flow and length.

Thanks for coming onto Heat Death, Gretchen. Tell me about the origin of Manhunt.

I got exposed to the right writing at the right time. I was toying around with this idea of trans-led horror, and having a hard time putting a finger on where exactly it should go, and who it should follow. Then my friend Alice Stoehr read The Screwfly Solution aloud to me when I was visiting her.

And that really put it in perspective for me. You have this story by Alice Sheldon, who wrote under the name James Tiptree about a mysterious virus, or some sort of force, infecting all the men on the planet, and driving them to rape and kill any woman they came into contact with.

Not only was this incredibly evocative, it has this enormous series of blindspots in it where you can tell any kind of story you want—because it's a very rigorously heterosexual and cisgender story. It's about the world as most people see it, and polite society breaking down in this explosion of violence. It's a very, very insightful story and it has a lot to say about marriage and fatherhood, and all the institutions in our culture that place women in men's power. But I realized that there was this whole world of stories in there about trans people, and queer people, and about how this affected them, and I thought oh, I could write that. I dashed off the first chapter in an afternoon.

Manhunt exists in this narrative tradition of "gender apocalypses," where one gender—men, women—is wholly transformed or disappears. (Y: The Last Man being a famous recent example in both comics and television.) Usually these stories don’t have a ton of time for people who transgress or don't meet these very typical gender binaries. What do you find particularly fascinating about interrogating those blind spots?

So much of the experience of being a trans person of my generation is being either invisible or a punchline. Finally we have a chance to be openly in the spotlight, and to connect to one another through our work. (And if some cis people see it along the way, I suppose I'll take their money.) But having an artistic heritage allows us to have a coherent idea of ourselves, and new ways to connect with one another. I think that's very exciting.

I think that gender apocalypses are a tremendously fertile playground, obviously. I wrote a whole book in it. And I think that rigidness of those conceptions of gender as they relate to these fictional apocalypses isn't necessarily a bad thing. The important part is following rigorously from the initial conceit.

How so?

In Manhunt, the virus that transforms men into cannibalistic monsters triggers this mutation only if the host has a certain amount of testosterone in their system. This means that many people that society would think of as cis women will also contract this virus, because they have polycystic ovarian syndrome, or any number of other chromosomal or genetic disorders that cause abnormally high testosterone levels. It also means that some people we would think of as cis men who have androgen or testosterone will not develop it.

And then, of course, you have people who are on testosterone exogenously—they're taking it as hormone replacement therapy, who are suddenly faced with a reality of "if I stay on this, I could lose my humanity and effectively die, and if I go off it, I may survive," but you'll have to face the rest of your life without the thing that has been making it bearable. And suddenly in this world, trans women who are on anti-androgens and estrogen—that medication is now life or death. Because if your testosterone levels get too high, you're going to become infected and live out the worst possible nightmare: to be forcibly transformed back into not just a man, but the most rabid, horrendous, sexually predatory man imaginable.

I want to include a quote here from a moment in the novel, where a character outlines that fear in a really direct way.

“That’s not a woman. It’s not your sister.” Her own hands were numb but steady on the handgun’s grip and over the other girl’s finger on the trigger. “It’s just a man in a disguise. We let it go, sooner or later it’s going to come out of its skin.” Her dry mouth. Tears stinging the corners of her eyes. “It’s going to hurt us. Rape us. Eat us, if it can.”

Manhunt essentially presents a world that's kind of a TERF (trans-exclusionary radical feminist) fever dream—that everyone born "male," whatever their gender identity, actually is this completely libidinal hyper-predatory entity. I found the way that you engaged with that fear really interesting, given how much you follow it to a logical conclusion.

Absolutely. As many readers have correctly divined, a lot of this book is really about how TERFs think, and how they see the world, and what the larger implication of those ways of seeing and believing are.

When you look at the world and see limitless hostility, and yourself as a potential victim in every situation, I think that inevitable result of that is fascism. Existing to divine the ways in which you are a martyr is a terrible way to live! And it also necessitates that you transform everyone around you into an oppressor in some way or another—even if you hold power over them. As we have watched cis women do to trans women over the last few decades.

How does that play out in the novel?

In the novel, a militant group of trans-exclusionary radical feminists have seized power in Maryland, and have spread up the east coast. As the novel begins, they're moving into New Hampshire and Massachusetts, and taking over the fragmentary local societies and governments that have sprung up. One of their driving goals is to find and exterminate any trans women, both for what they view as the concrete crime of being a potential viral threat, and for the existential threat of taking womanhood away from them. They view the trans womens' existence as the potential end of womanhood itself.

And there are TERF perspectives in this novel. I wanted to get across the violence inherent in this way of existence—the intentional process of poisoning yourself to the point that you can non longer have reasonable thoughts, and you are no longer existing in the world as it is. You're living in this shadow world built out of systematic delusions, and you've successfully excused your own violence by concocting an army of bogeyman.

You were pretty rigorously fair to your transphobic characters, I thought. You take the fear and what that fear does to the mind really seriously. They're the people walking around with guns, and they're still convinced that they're the ones with no power.

Exactly. You've built a world where the only way you can make sense of yourself is as an endangered, delicate victim. You're so locked into this classic white womanhood mode of weaponized victimization that there's nothing outside it.

That notion of victimhood excusing intimate cruelty and violence pops up elsewhere in the novel too. Here’s a selection that jumped out at me:

“Beth thought for a moment of the world that had been, of the flurries of callout posts, the texts asking her why she’d hung out with so-and-so when didn’t she know they were problematic, that they’d broken boundaries or gaslit someone or said the word 'sex' where a kid might have overheard. There had been pain in there, too. Real pain swirling through a farrago of social justice buzzwords and ruthless self-professed socialists whose politics hewed closer to Nancy Reagan than to Marx or Engels.”

There are a bunch of moments in the book where you look at the ways in which intentional queer communities can fall into similar traps—a lot of nice words about solidarity, and then suddenly you're out.

That's a big part of the book too! The lack of real bonds among queer people. That even after we come out, we've still been raised in the society that we were raised in—the homophobic, transphobic, misogynistic soup of modern America. And before we can uproot those beliefs, many of us just learned to paper over them with the right words. And then you wind up with someone who knows how to talk about their own prejudices as though those prejudices are actually enlightened.

The very influential psychological writer Lundy Bancroft—who wrote Why Does He Do That, a book about male abusers—wrote that often, what talk therapy will do for an abusive man is make him a more happy and well-adjusted and competent abuser. Someone who is able to frame his abuses in more deniable and socially acceptable ways. Who knows the right language to make himself seem like a victim of his own urges.

[Which is] a little bit ironic, considering that [Bancroft] wound up being a sort of bananas TERF himself.

I think there's a fair amount of that in the queer community as well. You encounter many people who have never done any serious introspection on their own transmisogyny or their own racism. They'll choose other words to fill in those gaps. They'll say coded things like "aggressive," or "problematic." Words that are vague but also kind of a call to action.

An undercurrent in all of this are the unexamined monsters that we carry in our heads and put out into the world, and the ways that collides with these real concerns about safety.

It seems like there’s a real conflict between recognizing danger, and adopting a mindset that means you will never, ever feel safe, no matter what your circumstances are.

Well, I think that the way we conceive of safety in America—especially now—a lot of it you can trace directly back to the rhetoric that came on the heels of 9/11. There was this sudden push to surveil everything, to inspect everything, to have armed guards and dogs and apparatuses of state to make sure we were safe. And what that really does is provoke paranoia.

When you're so invested in thinking of yourself only in terms of victimhood, that same emergent behavior will shape the society that you create. And unfortunately, many of us never learned to stop doing this, and in fact will find communities and places where that kind of thinking is encouraged and exacerbated.

The obvious point of comparison are these online communities that initially offer support but seemingly inevitably turn into their own sorts of witch hunts. There's a friend of mine whose doctoral research involves spending a lot of time on websites like r/fakingit, where people who have chronic diseases try and suss out whether or not someone else online is faking a chronic illness. And of course, they're all constantly accusing each other of faking it.

How then do you balance the knowledge of living in an unsafe world, without fully submitting yourself to these internally and externally destructive modes of thought?

Well, my personal way of being and belief is that we're never going to be safe. Nobody is ever going to be safe. And you have to learn to live with that uncertainty, because the alternative is insanity. That's a quick blunt answer, but that's what it took for me. Because there have been times in my life where it was very appealing to retreat into this idea of myself as a perpetual victim—especially when I have actually been victimized in really obvious public ways.

Ultimately though, I don't like how that victimhood makes me feel. I don't want to exist that way, I don't want to accidentally project that onto someone else and perpetuate the same violence I've experienced. I want to spend my life trying to open up. And I think ultimately you just have to decide to do that, even knowing that you could experience pain as a result. Because the reality is that you'll experience pain no matter what.

All human connection includes strife, you know?

That leads nicely into another aspect of the book, which is how much of a role desire plays in it. Having desire — or being desired, or feeling shame around desire—it's a very romantic and, in places, really sexy book.

Well, I wanted to be as true to the experience of having desires as someone who is, in many situations, not just socially undesirable but repellent and potentially monstrous. When you've spent your whole life—and now a good part of your adult life—as a fat person first, and then a fat transwoman, it's very easy to think of your desire for other people as something loathsome. A burden that you would place on them by expressing it. That's important for me to express.

I also want to reach out to other trans people through my work and let them know that that's not something they're alone in feeling—that that's a common sensation for many, many types of people, even people largely considered conventionally attractive. I also wanted to express the wild and particular joy of moving past that, as a freak at the edge of society. Of finding a way to say what you feel, and express love and ecstasy and desire.

You know, so much modern media is so sexless, or sort of anti-sexual. That's not how I write. My writing is very focused on sexuality and sensuality, because those things are important to me, and I think they're important to humanity. If I'm going to write a character, then I'm going to have to write about their inner sexuality and their sex lives, because that's how I understand these fictional people I come up with.

You've written online about the puritanical streak in a lot of mass media, and there have been interminable rounds of conversation online about whether or not sex scenes belong in movies or fiction, generally. (Mostly the people who say “no” have won.) What do you think we miss when that material isn't there?

I think you create a siloing effect, where by its absence you imply that sexuality doesn't belong in mainstream society. You imply that it doesn't belong in an adult's outward-facing personality. That letting other people see a sexual side of you—or understand that you have sexual desire—is a violent act in and of itself. And I have no patience for any of that.

I think that the vast majority of human beings are now and always have been motivated in large or small part by sexual desire. I just can't imagine writing a book where it wasn't important, and when I've read books where it wasn't important, they have felt tinny and incomplete to me.

God knows, there's endless numbers of conversations to be had about Harry Potter and its impact on culture, and the ways that it's mutated culturally as J.K Rowling has revealed herself to be more and more loathsome. But the weirdest aspect for me was the question of how none of them are having sex. How are they not fucking? That's insane to me. This is a bunch of teenagers with no adult supervision!

Right. Even if they're not fucking onscreen, as it were, how are they not at least wanting to? There's some lip-service to the idea of desire, but it's pretty thin stuff.

Everyone might as well be a Ken doll. It's very squeamish. I've read young adult books when I was younger like Monica Furlong's Wise Child and Juniper, books where sexuality was a real force. Kids are already beginning to grapple with that. So you are showing them this world where something is completely absent, and the implication is because it's not okay to show.

It's sort of akin to the way that we talk about art with no queer people, or no people of color.

Interesting. Say more about that.

Well, you're telling the reader passively what is and isn't worthy of attention, and what is and isn't worthy of making art about. I think discomfort as it sculpts fiction can, in turn, sculpt the things that people want to think about and create for themselves.

On a different note, Manhunt also spends a lot of time on the beauty of the New Hampshire wilderness. There's a strong sense that the ecosystem is more or less continuing on, which is a facet of a post-apocalypse that stories tend to skip. How were you thinking about the role of nature in the story and setting?

I grew up wandering the woods and traipsing through swamps with my dog. Hunting salamanders and snakes. I was a very outdoorsy kid! I'm not a very outdoorsy adult, but it's still very important to me, and it holds a lot of real estate in my heart.

It's part of the way that I get through life in this hellscape—reminding myself that long after human beings are wiped away, there will be life on this planet, and it'll go on without us, and it will have all sorts of strange and wonderful and terrifying experiences. The world doesn't revolve around us. The little human drama in Manhunt is just one small part of what's happening at the end of the world.

As much as menace lurks continually around the edges of Manhunter, there's so much beauty in the world, too. The awful things that are happening occur alongside profound beauty, and neither cancels out the other.

Yeah. I wrote one scene where an elephant appears while the characters are out scavenging, and it's escaped from a zoo somewhere in the area. And they all have this moment where they're just staring at it in disbelief. And I wanted the reader to really understand that's also life moving forward. That's also an entire world of experience that's just as meaningful — and just as meaningless — as ours.

What's your favorite fictional apocalypse?

I'm a big fan of A Canticle for Leibowitz, which I think is humorous and generous and bittersweet about the ways that humans construct societies. I'm a big fan of McCarthy's The Road, which is a popular answer but deserves it. He really codified what it was to be unromantic about extremity—to look at extreme experiences of deprivation and pain and terror, and to admit that they weren't for anything, that they just...happened. And that's the real naked horror of them.

I'm also a huge fan of Octavia Butler's Parable of the Sower and its sequels. There's this modern wave of people claiming that fiction has to show us some hopeful, better future world, which I think is horseshit. But Butler, in a way, does that. She shows us this act of carrying water as society crumbles. She's not afraid to make it deeply complex, to comment on economic inequality among black families, and class treachery, and that sort of thing. In-group and out-group violence. And the end result is more hopeful than any "here's how to build a utopia" story possibly could be, because it's about the stewarding and shepherding of life for its own sake.

So how did it feel to kill off J.K Rowling in this book?

Fantastic. I would do it again. I'm very glad that I fought past my hesitancy and included a chapter where a character recounts a ghost story about feral infected plague victims eating her and all her rich friends.

What's next?

My next novel, which will also be coming out with Tor's Nightfire imprint. It's a body-snatcher novel about a group of queer and trans teens who are sent to conversion therapy camp in the mid 1990s. And after they arrive in the middle of the Utah desert, they discover that something at the camp is creating compliant, heterosexual copies of the teenagers who are sent there, and sending the copies home to the parents. I'm very excited about it.

Can't wait. Thanks so much for coming on.

Thanks for such a thoughtful interview.

Gretchen Felker-Martin is a horror writer and critic at large. You can read her fiction and film criticism on Patreon and at Nylon, The Outline, Fanbyte, and more. You can follow her at @scumbelievable on Twitter. And make sure to preorder Manhunt here, or grab your copy wherever finer books are sold.

This has been Heat Death! If you like what we do here, sign up for the newsletter, or support us to the tune of 5$ a month.

Member discussion