Lions at the Kitchen Table

In 1862, workers in the British mill-city of Manchester met to decide whether to give up their own incomes in the name of other people’s freedom.

It was two years into the American Civil War, and a Union blockade of the Southern states had cut off the flow of raw cotton to the British mills. With more than a billion pounds a year of Liverpool-bound cotton trapped within the South by federal gunboats, those factories that couldn’t replace their supply with plants from Egypt or India cotton went dark. Before the war, the region’s mills had produced enough woven cloth to lasso the Moon three times over; by 1862, production had crashed. Unemployment surged. Workers went hungry and cold, and were thrown out of housing. Charities ran out of dole money, and when some tried to pay with scrip, workers rioted.

Back then, it was common for newspapers and magazines to run poems — a kind of editorial in verse. As one such poem in The Blackburn Times had it:

See that mother’s dire distresses,

For with shuddering heart she knows

That the babe she fondly presses,

Day by day still lighter grows

The rebellious South had significant support in Britain. In the mill towns of Northern England, factory owners — watching their over-leveraged factories fail for lack of fiber — demanded that Parliament drop its wary neutrality, recognize the Confederacy and send the world-dominating Royal Navy to break the blockade and reopen the flow of cotton. This would perhaps have been an economically sound measure: in many circles, it would even have been popular. That December, Confederate flags flew across the North of England; establishment magazines agitated for war. In “How We’ll Break the Blockade,” the satirical British magazine Punch wrote of “Cousin Jonathan,” the British metonym for the stodgy, and presumably abolitionist, New Englander:

We’ll break your blockade, Cousin Jonathan, yet

Yes, darn our old stocking, we will

And the cotton we’ll have, and to work we will set

Every Lancashire hand, every Manchester mill.

For the workers on Manchester, therefore, 1862 marked a particularly stark choice: throw their support behind a new war which would put them back to work, sparing them the prospect of destitution — or choose to make do, indefinitely, in the uncertain hope of advancing the nebulous cause of freedom.

A decision with significant resonances for today.

This is Heat Death, the newsletter that always knows for whom the cotton gins. Some quick business: Asher has recently had a pretty productive week, with coverage of two interesting science stories in two different places. First, he wrote about surprisingly social serpents (cuddling rattlesnakes, cliquish garter snakes and bonding ball pythons) in National Geographic.

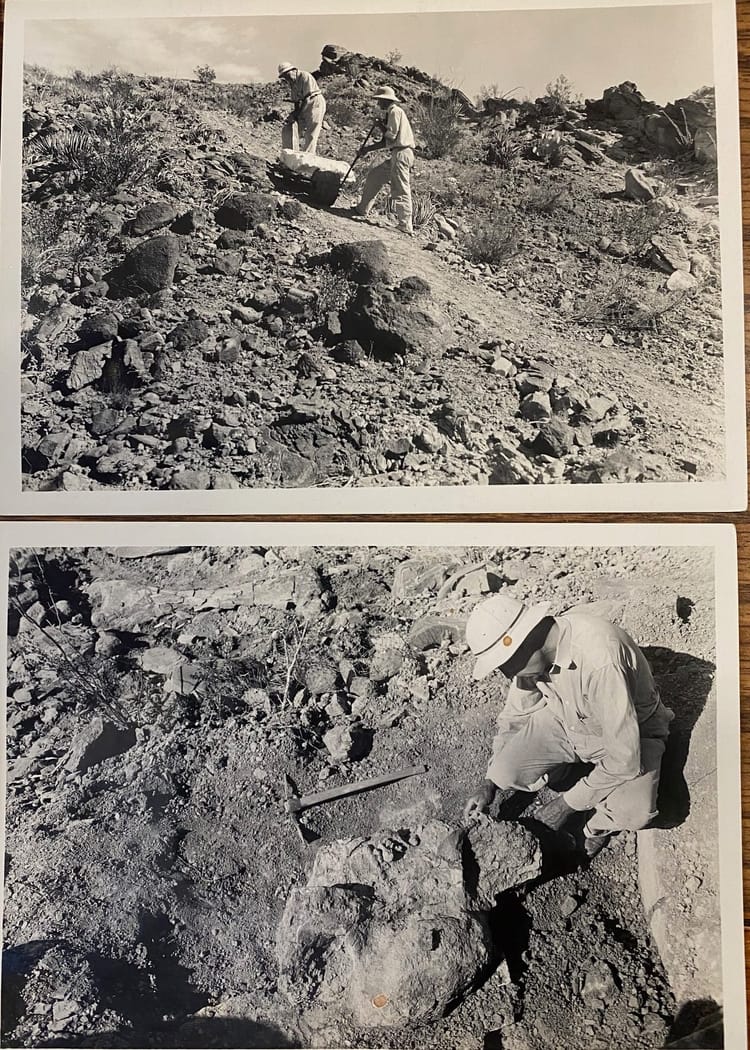

Then, he covered a minor paleontological bombshell: the revelation that many of the small tyrannosaurs from the latest Cretaceous of North America were – contrary to widely held beliefs and after a 40 year acrimonious debate – an entirely separate animal called Nanotyrannus.

Otherwise, he is now finally settling into writing the history of Texas paleontology for UT Press that he's long been researching, of which we'll share more down the line. For now, our mind is on much more recent history – and the lessons we can potentially draw from it.

This is Heat Death. Stay with us.

Saul here. On November 5th, Democrats won smashing victories across the country, particularly in New York City, Virginia and New Jersey.

On their own terms, these marked a stark political reversal for the MAGA movement — an electoral bloodbath that signals dire fortunes for the Trump coalition, should it ever again be so incautious as to subject itself to another fair election.

But we at Heat Death are not concerned with day-to-day partisan politics. We’re more interested in the realm they arise from: that of mass myth, where consensus grows and ossifies, creating a sense of how the world works that slips as a mask over the world itself.

A good example of this can be found inTrump’s 1.5 percent margin victory last November, which became part of an interlocking system of belief arguing, in effect, that his victory had been not just an event but a portent. Harris, proponents of this view argued, had lost as a result not just of a series of unforced false steps by the Democrats against the backdrop of the public abomination of Gaza, and certainly not as part of anything so prosaic as the global anti-incumbent wave let loose by Covid-19 and inflationary pressures. Rather, mainstream pundits announced, she had been the victim of A Permanent Shift in Vibes. They argued that number of crucial demographics — young men, Black people, Latinos — had flipped, birthing a new era of indefinite Republican rule.

At the time, it was hard to tell how many of these swings were trends, and how many were simple odd statistical artifacts of a bizarre election. It’s true that the young men who showed up at the polls last November went +12 percent for Trump, as opposed to +1 percent for Biden in 2020. Yet their demographic also showed up in historically low numbers. One might ask: had Trump benefited from a surge in youth support, then, or a kind of selection bias? Was his win in that demographic, in other words, simply a result of the fact that MAGA had courted its young base on their chosen media platforms, while the Democrats ignored or attacked theirs?

These were potentially productive questions, but not — in some quarters — popular ones. Over the last year, pundits instead turned these statistical factoids into the undergirdings of a new mythos: the idea that Democrats were losing their base. Over what? Their refusal to focus on “kitchen table issues.”

Deployed in battles within the broad Democratic coalition, “kitchen table issues” is a quick-and-dirty metonym for an entire worldview. Namely, that the party’s failure in 2024 was to lose touch with the lived economic reality of its base. That they had tried to sell highfalutin’ abstract notions — climate action, environmental justice, trans rights, “democracy,”— that animated the foundations and coalitions of progressive nonprofits known as “the groups,” while alienating ‘ordinary’ people.

After the Democratic rout in 2024, this has generally been memed as the idea that Trump had won because of “the price of eggs.” Some writers have made a lot of hay over the Republican’s “Kamala is for they/them, President Trump is for you” line.

But it goes beyond that. More recently, I’ve been seeing it in the climate space, particularly in renewable energy industry circles on LinkedIn. In those circles, there’s a furious fight raging over whether the progressive focus on “climate” and in particular “environmental justice” helped sow the seeds for the current right-wing reaction.

You can see this push at The Dispatch, which argued last month for the “End of the Climate Hawk Era” — the period when rapid decarbonization was believed to be both possible and essential — and at Latitude Media, where a recent panel argued that the progressive focus on “bundling” climate with issues like immigration or housing had turned median voters off, and that the climate movement should focus on, yes, “kitchen table issues.”

There is something to this argument. “Climate,” as an issue — in the sense of the global campaign for emission reduction — really does often feel hopelessly abstract, diffuse and depressing — particularly when compared to the concrete, rapid and gee-whiz advances in renewables technology over the past decade. Adding to the problem is the fact that climate groups, like civil society writ large, suffer from their reliance on big donors and family foundations for support — foundations which have a habit of releasing periodically-shuffled lists of new jargon that projects must include in order to be funded. These, naturally, are often quite divorced from how normal people talk, and often reflect the particular and peculiar concerns of specific wealthy benefactors.

The Trump administration, of course, has its own set of wealthy donors with particular bugabears, and in this light, the Trump administration's crusade against once-orthodox buzzwords like “diversity, equity and inclusion” or “environmental justice” or even “climate change” is both a reaction to this trend of abstracted elite discourse and — it’s worth pointing out — a perfect example of it.

Last week’s decisive wins for Democrats — happening in a context of rising prices for food and electricity, as well as spiking health insurance premiums — have reinforced this basic construction: The idea that people will turn against Trump because of “affordability.”

There is, again, something to this. Prices really are going up as a result of an economic platform — if you can call it that — that veers wildly between the confounding and the openly corrupt. And yet the focus on “the economy, stupid” leaves out something very important. In fact, it cedes the terrain on which to fight for the future to the very world view that is strangling it.

Which brings me back around to the workers of 1862 Manchester, leaving their chilly, bare-cupboarded rooms to meet and argue over whether they should demand their representatives go to war against abolitionists to get them back to work.

Heat Death is an entirely reader-supported newsletter, and all proceeds go toward paying guest writers and maintaining our web-hosting.

If you enjoy what we do here, please leave us a tip or sign up: paid subscriptions are just $2-$5 a month.

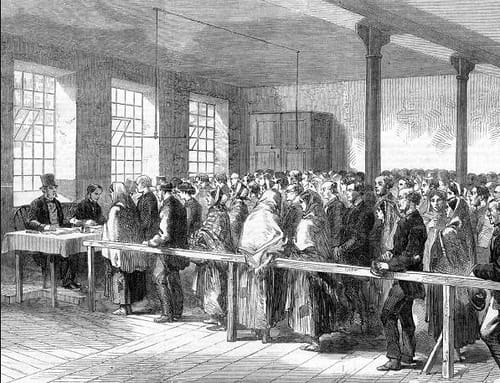

Let’s set the scene a bit more. It was a frosty evening, the week after a meager Christmas, and thousands of workers streamed through the ornate brick archways of the Manchester Free Trade Hall.

The industries of Manchester had long been built on enclosure and dismal working conditions. Unions were illegal. Any organizing for better working conditions or the right to vote could easily get you imprisoned, executed, or sent on a permanent trip to the penal colony of Australia. In 1819, an epochal demonstration of 60,000 Chartists gathered on St Peter’s Fields in favor of universal male suffrage — a display so threatening that the local government ordered cavalry to break it up with drawn sabers, killing perhaps a dozen in the infamous Peterloo Massacre.

In subsequent decades, the site of that demonstration also housed temporary meetinghouses where workers organized for decades against the Corn Laws, a protectionist policy which benefited wealthy landowners — and fleeced or starved the working class — by banning the import of cheap foreign grains. And Manchester, — whose workers upcycled the cotton produced by brutal enslaved labor — had long been a center of the British anti-slavery movement; a perennial stopping-point for American abolitionists touring Europe.

Both of these were fights that Manchester’s radicals won. Britain banned the slave trade in 1833. In 1846, a cross-British coalition won the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 — and the magisterial Manchester Free Trade Hall was built on the old St. Peter’s Fields in celebration. That same year, Frederick Douglass gave a thundering address in the new hall on the “evangelical man stealers” of the South, where as in England

the abolitionists have to contend with the religious classes of the community; for slavery is defended on religious grounds. It was part and parcel of the religion of the land. Men were sold to build churches, women were sold to support missionaries, and babes were sold to buy Bibles for the heathen. Individuals dying bequeathed three-fourths of their slaves to be sold, that the Gospel might be sent to the heathen. And they were denounced for being infidels to such a religion.

The building the workers entered, therefore, was a monument to the lengths that the powers-that-be would go to lock the working class out of power — and a concrete symbol that organized opposition could jimmy that sealed door back open.

And so it was on New Year’s Eve 1862 that the thousands of workers met to ratify a motion in support of the Union and the blockade that had put them out of work. They wrote Abraham Lincoln personally that the Union’s victories at pivotal battles like Antietam:

fills us with hope that every stain on your freedom will shortly be removed, and that the erasure of that foul blot on civilisation and Christianity – chattel slavery – during your presidency, will cause the name of Abraham Lincoln to be honoured and revered by posterity.

In a testament to the importance of the moment, Lincoln wrote back, in a letter that is engraved in a statue that stands near the old Free Trade Hall. He laments that the

[t]hrough the actions of our disloyal citizens the workingmen of Europe have been subjected to a severe trial, for the purpose of forcing their sanction to that attempt. Under these circumstances, I cannot but regard your decisive utterance upon the question as an instance of sublime Christian heroism which has not been surpassed in any age or in any country.

These workers, to be clear, were one interest group, however dominant. They didn’t speak for all Lancashire workers, and soon after these events, a competing pro-Southern workingman’s society set itself up to agitate more forcefully for war.

But this moment is worth belaboring, because it’s one that should be a case study in our politics. Because the workers who met to declare their hatred of slavery did all this in spite of editorials in the leading city newspaper, the Manchester Guardian — yes, that Guardian — urging them to stay home. In spite of the powerful millowners who employed them, many of whom were organizing in favor of war. And, crucially, in spite of their own economic self interest.

Let’s really hold a magnifying glass on that idea of economic self interest, particularly the impoverished way that it has been defined in modern debate. Let’s do so by talking about “the price of eggs.”

Today, the idea of “the price of eggs” means nothing more than the dollars and cents a customer pays at the grocery store, just as the price of electricity is nothing more than the total of your monthly bill. The marginal “consumer” — note, please, that word — is not expected to care about the fate of chickens, or workers, or the health of the polity as a whole; they will not, in this construction, ever choose to pay more to secure the health of the land, or water, or future generations.

Notably, this isn’t true: sales of cage-free eggs, as Bloomberg notes, are booming despite their increased cost. More importantly, high prices, in our economic system, are often a symptom of something more fundamental. In March, antitrust lawyer Basel Musharbash argued in BIG that eggs specifically are so expensive because

a small number of actors have secured chokepoints at key links in the egg supply chain, and are using them to keep egg production throttled even in the face of shortages and high prices — which in turn keeps the shortages and high prices going.

That’s part of a much broader problem of giant corporations controlling the American food system in a way that has turned farmers in key industries like chicken, pork, dairy and (increasingly) beef into something like highly-leveraged serfs — a partial explanation, as researcher Austin Frerick argues in Barons, for why the rich black soil of Iowa now grows mostly corn and soy, with an increasingly unhealthy population forced to import all of the crops a person might actually put on their table.

This is a situation, by the way, that Joe Biden explicitly ran on changing, and throughout his presidency he would make noises about meaningfully breaking up the meat monopolies. And then he just … wouldn’t. He picked as head of USDA Tom Vilsack, a dairy lobbyist who had overseen the near-destruction of the independent dairy industry under Obama before skipping over into the private sector. During Biden’s term, I was continually on the phone with progressive farm groups who were animated, then incensed, and finally heartbroken by how little the Democrats had actually done with the anti-monopoly platform they had promised.

And then, when his successor lost, I saw everywhere the idea that Democrats had lost because “consumers” had been distracted from the battle for democracy by the price of eggs. As though these fights were not, in some very real sense, one and the same.

For the Manchester Chartists — the pro-democracy movement that helped birth that 1862 meeting at the Free Trade Hall — the battle was about economics, in the literal sense that means “freedom of choice.” Yes, they wanted good wages and affordable food and time off. But their balance sheet looked different; it included the possibility that low prices and good wages might come at an unacceptable cost. That slave labor was not just immoral but a clear and present threat. During the 1862 blockade unrest, in the mill-town of Ashton-under-Lyne, radical leader Ernest Jones told a crowd of British working people that the slaveholding South was

"the enemy of your trade, the foe of your freedom, a standing threat to your property. Slave labour is direct aggression on the free labour of the world."

He added that “the key that shall reopen our closed factories is the sword of the victorious North.”

And he was right. Britain, despite the pleading of the mill owners and other hawks, never came into the war on the Confederate side. British workers suffered through another hard 18 months. Many made it through by mutual aid. Local authorities got creative in their interpretation of welfare laws, which included a work requirement — an obligation that tens of thousands of men and women met by participating in “sewing schools,” which often also taught reading, writing and industrial skills. In 1864, the government approved loans for infrastructure spending to build canals, roads and bridges — projects that presaged the jobs programs of the American New Deal generations later.

But by 1864, cotton from the occupied South was flowing again. By 1865 the trade had resumed, and the famine was over. A situation prophesied by a March 1863 poem, which contrasted the grim Christmas of 1862 to the brighter times to come:

England! thy Christmas mirth is mixed with tears —

A nobler thrice bless’d commerce shall be thine,

Stain’d with the guilt of slavery no more.

There are a few propositions I’d like to draw from this episode, for the climate movement and our politics at large.

- We need a bigger politics. “Kitchen table politics,” reflects a reality that what people discuss in the halls of state should, in some sense, reflect what people are discussing with their families and friends. But it tends to leave out a moral dimension that, for many people, makes life worth living. It falls prey to a brutal shrinking of human perspective, and a dismissal of the idea of the human soul. It reduces the populace to a collective of relentlessly optimizing automata who will back any measure that brings prices down and wages up, whatever its foreign horror or long-term cost.

But man does not live by bread alone. “Kitchen table politics” often leaves out what really happens at the kitchen table. It’s the place where we gather with our friends and families: the people with whom our relationships are closest, and with whom, not incidentally, those bonds are largely free from the world of commerce, commodity and money.

Folded in the web with these relationships, we can take refuge for a while from the howling winds of the market before, inevitably, we must venture again outside.

A successful politics recognizes that we all face that storm. But it does not act like it’s where most of us want to be spending our time. - Affordability is a two-edged sword. Small-l liberal — to say nothing of left — politics is very hard work. It requires building coalitions of people of very different interests to work together for long periods towards a common goal. We might ask what is more likely to sustain that work, in the case of, say, climate politics: the shared prospect of handing the green temperate world you were given to your children and grandchildren — or the prospect of a 20% cheaper electric bill?

And there is a hidden danger in the theoretically simple idea of affordability. It’s easy to state that an electric bill is cheaper when it comes from “clean” sources. But can you guarantee us? What happens when that calculus shifts?

Here’s the thing about fossil fuels: they are, in one sense, quite cheap. They have to be. They are the result of millions of years of solar energy being painstakingly stored by plants and animals — tiny islands of order in a universe that tends always to chaos — compressed and refined within the heat and pressure of the Earth. To stoke the fuel made eons. To light the match takes but a second. The future always bears the bill.

That ever deferred payback is the most insidious part of the fossil trap, because it means that, even as we are buffeted today by storms fueled by what we burned a generation ago — it still makes sense to keep burning them!

That’s in large part because fossil fuels are, like chattel slavery, a means of unparalleled control over the ability to do work. Up until the very recent mainstreaming of the lithium ion battery, piles of coal, barrels of diesel, propane, and gasoline marked the only way to store energy for on-demand industrial use. In the current paradigm, if you think your city is going to be hit by a hurricane, it makes more sense to have a full house, gas generator than it does solar battery and back up.

A politics that successfully confronts this trap has to be able to do more than say “actually, renewables are cheaper!” It has to be able to find ways that bind people together when it is time to do hard things or make sacrifices. The path out of where we are cannot be one of ever-increasing cheapness and leisure, or it will fail when, for example, the next state-subsidized fracking boom happens.

It has, to put that another way, to be able to confront the core assumption at the heart of “cheap is the same thing as good.” - It’s about control, stupid. The workers in Manchester fought for economic rights, which is to say control over their own lives. Their struggle ultimately succeeded because this was both moral and practical.

That element of control is central to the fossil fuel economy — going back to those British factories in places like Manchester.

In Fossil Capital, the Swedish economist Andreas Malm argues that the coal power mills that we identify with the industrial revolution superseded hydropower mills not because they were more efficient — for a long time in the early 19th century river powered Mills were better, particularly when knitted together by landscape-scale engineering projects to change the flow of water — but because the ability to generate power on demand opened up production lines that liberated millowners from the need to compromise with either skilled workers or each other.

There are clear analogs today. Electricity prices are rising because the Trump administration — whose energy policy hubs are largely staffed by fossil fuel executives and insiders — has thrown its entire weight behind upholding the cause of independent oilmen and frackers, and crushing the wind and solar industries.

Or take the AI industry, whose vast valuation rests on the idea that it will successfully allow big business to slash millions of jobs. One of the main things that industry needs is on-demand power — and now as ever, the only way to generate that power is with fossil fuels. Across the U.S., data centers are signing deals for city-scale gas power plants that will power their operations. Which is to say, if mass unemployment comes, the technologies that bring it will run on fracked gas. - A good movement is a good hang. And maybe the most important thing is this: politics is hard and drudgerous. A sustainable movement facing adversity has to be a community. It has to have cross-cutting relationships among its members. It has to provide a way for low-grade friction and stress to force people to overcome small indignities together that make them close and trust each other, and also has to provide chances to hang out and meet people. A revolution, as Emma Goldman said, is a thing you can dance to.

On the one hand, a failing of much of the Trump-era protest movement — with No Kings as a promising but partial exception — has been that while they can get millions into the streets, they are often millions of atomized individuals who do not come to know each other through the process of participation: they go out, show off their signs, and come home.

On the other, I think too much focus has been paid to the explicit politics of the Zohran Mamdani campaign — the Rooseveltian democratic socialism, the experiments with free buses and city-owned groceries — and far too little to what the campaign represented structurally: a chance to get off your phone and meet people; an exciting space to do meaningful work together.

As The New York Times reported in an article about how the loneliness of 20 somethings propelled Mamdani’s rise:

Addicted to their screens, strapped for cash, spiritually unmoored and socially stunted by the pandemic, young New Yorkers needed a reason to get out of the house. They found it in Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral run.

“It’s honestly what I would prescribe for the loneliness epidemic,” said Tal Frieden, 28, at a rally in Sunset Park the Sunday before Election Day.

The creation of a mass campaign like this relies on a kind of meta-politics: the belief that association and relationship building are good and worthwhile. That it is worth doing hard things together. The explicit politics of a movement like that can look very different, and should — should rise, organically, in other words out of the specific interests and beliefs of the people so organized.

But I’m drawn to the image of those tens of thousands of people in 1819 St. Peter’s Field, on the site of what would later become the Manchester Free Trade Hall, facing off against government cavalry for the right to vote — for a measure of dignity and control over their own lives, and how their country was governed.

None of them would live to see the victory. Only in 1918, exactly a century later, did a liberal Parliament — pressed by the need to deliver troops for last push against Germany in World War I — pass full male suffrage.

But that victory only became possible because for four generations, men and women braved the transport ship and the noose to fight for a future in which they and their children — and other people’s children — could be something that we recognize as free. Their willingness to do that, and the means by which that forward motion was maintained, point the way to a broader sort of politics in our own age.

Or as Percy Shelley wrote in the wake of the St. Peter’s Field Massacre:

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number,

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you –

You are many – they are few.

Author’s note: For Civil War and economic history nerds, poems in this essay come from a wonderful and bizarre online archive of Poems of the Lancashire Cotton Famine that is preserved by the University of Exeter. The poems have interesting annotation and historical context, and some are quite fun in a weird sort of way, not least because they come out of such a different tradition of mass media.

A few of these are syndicated from Confederate or Union newspapers, which had poem columnists too. One personal favorite is this 1861 satire reprinted from the Richmond Whig, hometown paper of a Confederate capital that is, three months after the capture of Fort Sumter, still very much feeling its oats and blissfully unaware of how badly the war they've started will ultimately go. In the crescendo, a buffoonish Lincoln, too deluded to realize that the South's victory is assured, tells a crowd of flunkies that if the Union wants to win:

Then sixty new iron-plate ships to stand shells

Are loudly demanded (must have ‘em) by Welles;

For England, the bully, won’t stand our blockade,

And insists that we shall not embarrass her trade;

But who fears the British? I’ll speedily tune ‘em

As sure as my name is E Pluribus Unum.

This has been Heat Death. We're entirely reader-supported independent media. If you like what we do here, feel free to subscribe: paid memberships are just $2 to $5 a month. (Or you can always leave us a tip.)

But while we're growing, the single most helpful thing you can do is send it to someone you think will like it or post it on your favorite social with a nice note. We are, above all, a word-of-mouth operation.

We'll be back soon with more musings on past, future, and all the crises in between. Until next time – keep the home fires burning.

Member discussion