Science Before Science with Adrienne Mayor

Saul here. Long before there were “dinosaurs,” there were dinosaurs — or rather, the strange bones that people dug up in quarries or that lay contorted and snarling from the sides of cliffs and creekbeds, inspiring folk cures and strange myths.

And because life on this planet is dangerous, precarious and yet at its core predictable, long before there was “science,” there was science: systems of testable propositions, subject to forms of peer review and quality control (potential mockery, accidental death).

And that long empirical tradition, wedded to hundreds of thousands of years of work on what we can fairly call bio-engineering, zoology and materials science, created a human civilizational package that is so fundamental that we wrongly think of it as primitive.

It turned wild plants into the crops we now eat; transformed wild animals into our aides and auxiliaries and transmogrified the detritus of earth — skins, wood or stone — into the dwellings, tools, weapons and boats that we used to conquer the Earth.

And in the far future, it will be how our descendants, crowding against the storms that shatter their cities, make sense of the grievously altered world we have left them.

This is Heat Death, the newsletter that knows we are doing everything right to be the mythic ancestors future generations curse. Our guest today is Stanford University historian Adrienne Mayor, who specializes in what we might call the paleontology of science: the deep roots of a tradition that she argues is more or less coequal with humanity itself.

Science, she tells Asher in the wide-ranging interview that follows, began perhaps millions of years ago, “as soon as human beings started investigating their landscape and their surroundings.”

Their conversations delves into the folklore of ancient fossils; how fast history decays if not transformed into myth; and how traditional stories encode hidden scientific truths about our world that have only recently been rediscovered — from the record of past ice ages to meteor collisions to warnings about the looming dangers of tsunamis and carbon-belching “death lakes.”

And she delves into how our descendants may use myth to make sense of our own age. As they examine the bones of our current age, who, she asks, “will believe that we once had 8 billion people?”

As always, this is Heat Death. Stay with us.

Heat Death is an entirely reader-supported newsletter, and all proceeds go toward paying guest writers and maintaining our web-hosting.

If you enjoy what we do here, please leave us a tip or sign up: paid subscriptions start at just $2-$5 a month.

Fossils into Folklore

Asher: You combine a couple of interesting fields: classics, folklore, and historian of what we might call early science. How did you get interested in drawing those together?

Adrienne Mayor: It's science before science, before historians of science. It's always frustrating to me that historians of science — and they have a whole society and everything, I belong to it — say that science starts in the 17th century. I think that the first inklings of science, the first impulses toward the scientific mindset happen as soon as human beings started investigating their landscape and their surroundings.

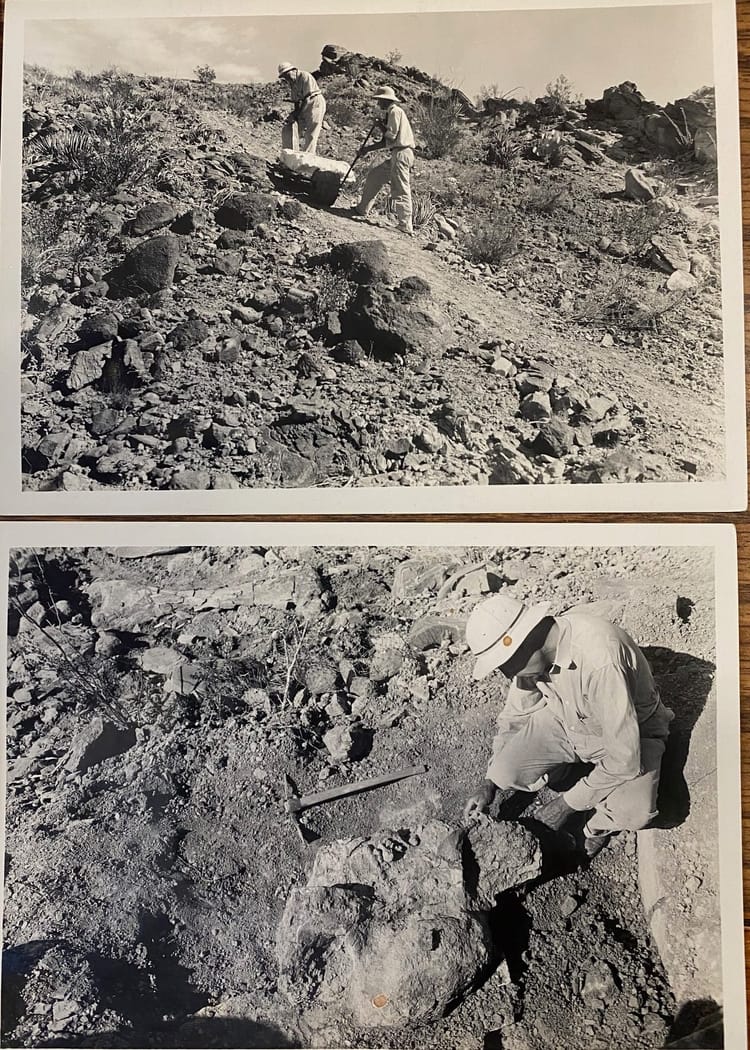

I grew up in South Dakota where there are a lot of fossils. And as a kid I always wondered, well, what did American Indians think about these remarkable remains? They were the first ones to see them, and I couldn't believe that no one had asked that question. And when I went to Greece for the first time, I was on the island of Samos and some farmer had plowed up a gigantic thigh bone, still encrusted with dirt. It was in the second story of a post office.

I said, you mean farmers are finding these whenever they plow? “Well, yes, they bring 'em into us.” And I said, well, they must've been finding these forever. Why hasn't anyone asked what they thought about them? That's how it began for me, really.

When you began looking into this, was there any existing framework of how people were thinking about the geology-inspired myths?

Not really. I read Greek and Latin texts in the Loeb editions, which have the Greek on one side, and the English translation on the other side. They’re really handy for me since I can pick out certain concepts and words in the ancient Greek, but I need the translation. So every time I would come across something that I felt there should be a footnote about, like “we found giant bones on this island,” or “an earthquake revealed a monstrous skeleton” there would be no footnote, no commentary, nothing. Every now and then, there would be a comment from some translator who would say, oh, I saw a large fossil in a museum somewhere nearby. But every time I talked to archaeologists or classical scholars or historians or historians of science, they would all say, well, there's no way you could find a pattern.

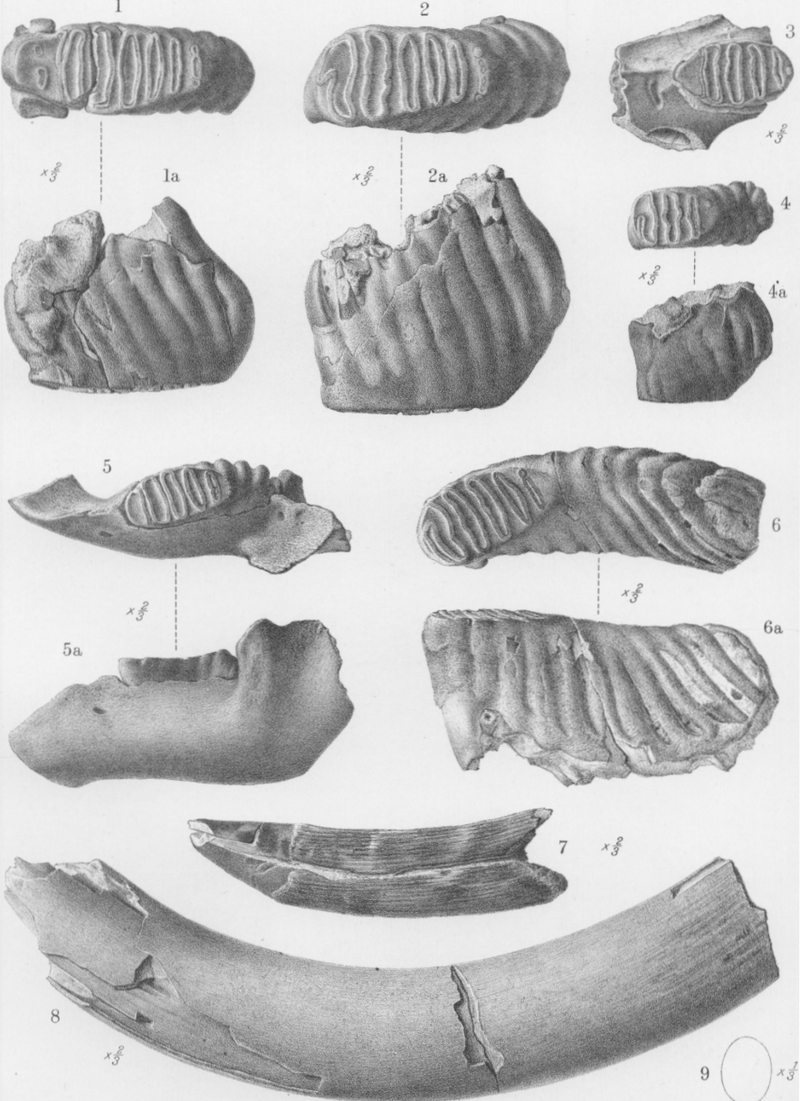

This was before the Internet, so none of this was indexed. No one was actually collecting that information. I just had to read through every single Greek and Roman text that I could find. My copies of the Loebs are just bristling with post-its for every discovery of remarkable bones or big footprints or giant teeth or things like that. Once I got all the Greek accounts, I collected over a hundred incidents of people finding remarkable remains — bones, teeth, tusks, footprints, things like that — and bringing them to temples. And they often told exactly where they found them. And though it's also very rare to have measurements in ancient texts, they actually measured the volume of skulls that they found and compared them to human bones.

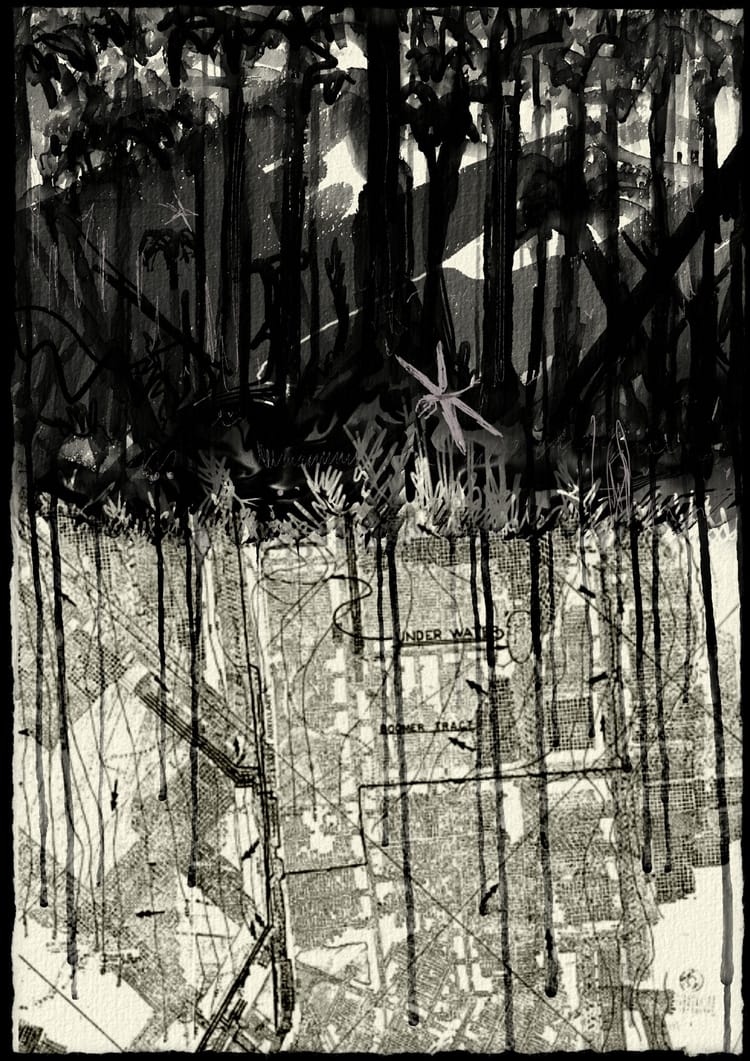

After I gathered all those, I had to find paleontologists who had worked in that Mediterranean area. And it turns out that there were paleontologists there, mostly from France in the 1870s. I finally was able to make a map of where fossil deposits were in the Mediterranean and then superimposed it on my own map of all the Greek examples. People were surprised that it mostly matched up. But no one had been working on the ancient interpretations and discoveries of fossils until I wrote that book, The First Fossil Hunters. Now there are other people who are now looking for oral stories and memories of fossils in Africa, in Australia, China.

What are some of the things they’re looking for?

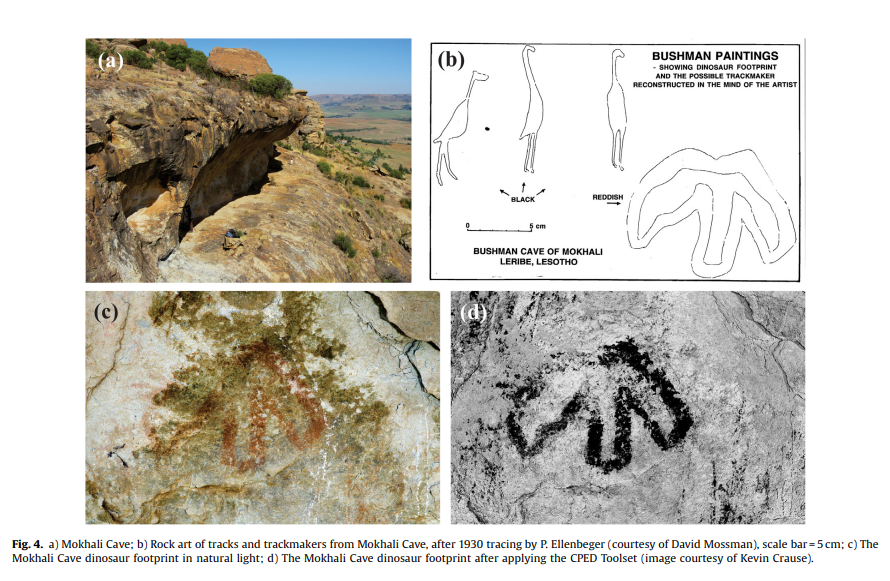

I've co-authored with Charles Helm and Julian Benoit in South Africa, who have a book coming out on Indigenous understandings of fossils in Africa. Benoit’s been asking about stories and explanations around fossil deposits of dinosaurs and other megafauna, and finding all kinds of interesting discoveries and then interpretations that are fairly rational, and relating that to rock art in Africa.

I've also worked with a paleontologist from China, named Lida Xing — we have co-authored three or four articles. He had read my books, First Fossil Hunters and Fossil Legends of the First Americans, and then applied that when he was studying paleontology in Toronto. And then went back to China and began asking peasants, farmers and people in villages about dinosaur tracks and talking with villagers about their stories related to dinosaur fossils. There’s another researcher, Dong Zhiming, who was the first to start actually asking peasants where they got the “dragon bones” to grind into dragon-bone medicine back in the nineties. They would show him, and it would turn out to be a deposit of dinosaur fossils. He found several new species that way.

In your new book, Mythopedia, you talk about a term for this sort of thing: "geomythology,” i.e the mythology inspired by physical features of the earth. How did that framework of folklore studies get started?

It’s an emerging field, but I would say that everyone considers Dorothy Vitaliano, a geologist at Indiana University, to be the founding mother. She was a geologist who had read some classical texts, especially Plato's thought experiment about Atlantis, and she was talking with classicists about whether there had been civilizations that might've been destroyed by catastrophic events, and whether those events would be remembered in folklore or myth. Her first book, Legends of the Earth, came out in the mid seventies. The field didn't really start to take off, I think until about the year 2000. It’s mainly a study of oral traditions that attempt to explain — or record — catastrophic natural events. Volcanoes or earthquakes or tsunamis, massive floods, extremely catastrophic fires. Even meteor impacts. The stories contain memories of those events. Sometimes they let us know what the impact was on the flora and fauna, and human reactions to it.

How did this particular book project come about? You've had a couple of more lengthy projects, like your book on The Amazons, or Fossil Legends of the First Americans. This one feels more of a compendium of things that interest you.

I signed a two book contract with Princeton in 2009, and they wanted something on geo-mythology. And that was perfect because geo-mythology is completely worldwide: I have stories from every corner of the world, from deep antiquity up to the modern times.

One big question about geo-mythology is just how long a tradition be preserved orally. Could a story about earthquakes or volcanoes be perpetuated? And it turns out those who study stories from [Australian] Aborigines about volcanoes, floods and fossils have found that they go back at least 20,000 years because those people are living in the exact same place for that long. They have a culture that really respects paying attention to oral mythology.

How do you date these myths?

The only way to date them is if they talk in enough detail about a dateable event — like an extinction of an animal, or an upheaval in the land. You can do that with the Aboriginal stories. The most famous example of this is the collapse of Mount Mazama, which created Crater Lake in Oregon. Scientists only recently figured out what the sequence of physical events was that created that lake. And then others noticed the oral traditions of the Klamath Indians, which are told in a very mythological language about gods and their activities. Yet if you pay attention to the details of how they say that Mount Mazama exploded, and what created the lake, earth scientists noticed that those details could only come from eyewitness accounts. Details that the scientists themselves only recently figured out from looking at the evidence.

So then you wonder, well, is there any proof that there could have been eyewitness of the creation of that lake? And in fact, yes. Recently they’ve found prehistoric sandals that can be dated, because the sandals are made of the same materials and patterns as founding Klamath graves that they can date. So not only can they date the physical events that caused the crater lake to be created, but they've also got the dated sandals both below and above the ash from the volcano. So we have two ways of dating that event. And so I think there's no doubt that they did have an eyewitness account of what happened there.

What are some examples of geo-mythology this you discuss in the book?

One of my favorite stories is the story of Rama's Bridge, a land bridge that’s sunk now between the tip of India and Sri Lanka. And in the Indian epic The Ramayana, the bridge was supposedly built by monkeys for the god Rama to cross from India to Sri Lanka to rescue a princess. I think it's very interesting that at that early date, people knew that there had been a land bridge there, and that they tried to explain how it could have been built.

They believed that the monkeys used floating stones. Well, that sounds like a very supernatural speculation, but it's actually, it turns out that a lot of the land bridge that still exists on the seabed between India and Sri Lanka is fossil coral, which can actually float. There are temples on either side of where the land bridge would've touched Sri Lanka and India, and in the temples you can buy souvenirs of floating stones, which are pieces of pumice or pieces of coral. So that's an example of some scientific reality embedded deeply in the myth.

I found your account of the Cameroonian death lakes particularly interesting as well.

Yes. In 1986, Lake Nyos in Cameroon exploded and the CO2 cloud killed almost 2000 people, and all the other living beings around that area. People had myths about the danger of that lake for centuries, and they didn't make their settlements near it, and they felt that they could tell which lakes were good and which were bad. Lake Nyos was one of the bad lakes. Fish did not live in that lake, and the colors were not like other lakes. I assume that they must have seen other evidence that gave them the idea that it was a sinister place. So no one settled there for centuries. Then new tribes came to the area and did not know that old folklore about the dangers of that leg and settled all around the lake. And those are the people who did not survive when it exploded.

So how do we tell when we're looking at stories that are rooted in scientific occurrences, rather than cultural narratives that aren’t directly tied to real events?? It seems like there’s a risk in this field of just-so stories.

That's why I focused on folklore or stories or traditions or oral traditions, legends that were about nature itself, about phenomena in nature, perplexing evidence that people would see in nature rather than just a simple good story As the Barbers have explained in their book When They Severed Earth From Sky: How The Human Mind Shapes Myth, legends about catastrophes are perpetuated because they contain early warning signs, things you should pay attention to just for survival. You can sense those in a lot of the geo-myths that are talking about disasters that happen in the landscape. There’s a focus on warning signs.

Like what?

Mythopedia has two essays on how people have survived tsunamis. Particularly the massive 2004 tsunami that killed over 250,000 people in Indonesia. In that region, there were one or two areas that didn’t suffer many deaths compared to the massive casualties that happened to everyone else. Why did these two places survive? Because they had in place very vivid folklore about tsunamis, and how to spot the warning signs, and they were able to spot that and save themselves.

The very interesting one is the people of Sumatra, which was the epicenter of that earthquake that then caused the tsunami. Yet the people of Onge in Sumatra survived. They had folklore about tsunamis, and they wove that folklore and the warning signs into nursery rhymes. It was in lullabies that people sang to their children. It was in all the schools. It was in all the love songs. It was just everywhere. Everyone knew exactly what to do when they saw the crabs coming out of the sea and running for high land, or the water starting to go away from the beach. Instead of running out on the beach, they went for the high places, where they had already built refuge areas because of their folklore.

And I just find that really fascinating. To have a story like that perpetuated over many generations, it has to be really an exciting, thrilling story, something that really captures your attention that you want to tell someone else and perpetuate. So it has to have that same quality that the stories about gods and heroes have, but embedded in there has to be the real natural knowledge that will save your life. I think it just has a lot more of a proactive feel to it rather than a just-so story. It actually embeds what to do, or how and why something happened related to the actual evidence in the earth.

Relatedly, one of the things you discuss in the book are possible geomythologies of the future.

I think it's fascinating to try and imagine what kind of folklore will be told millennia from now. If there are human beings, people are going to try and explain things. I just think that's a sort of timeless and universal impulse. And so how will people try to explain what happened with climate change? We already know that indigenous people in South America are noticing and giving explanations for the fact that the glaciers are retreating.

Imagine, for instance, between earthquakes and fracking. If we continue to do a lot of fracking in places that aren't usually known for earthquakes and then earthquakes are suddenly being noticed there, I think that's a possibility for a kind of cautionary mythology that could arise.

Right. We delved too greedily and too deep, and the earth got mad and started trying to shake us off.

Or who will believe that we once had 8 billion people? I mean, maybe we're going to go back to the Stone Age, when there are only a relatively few people, and no one will believe that there were that many. And yet they'll come across graves and evidence that there were very high populations in various areas. How will people explain that there were once glaciers. Or say the big one — the major earthquake — happens on the Pacific coast of California. How will people explain that huge drop off? I think that's a fascinating thing, to try to imagine what kind of stories will be told.

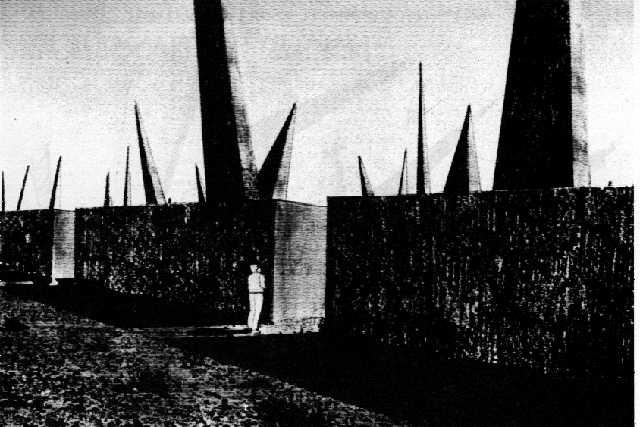

In my book on biological and chemical warfare and antiquity, I have an epilogue where I talked to people who try to figure out where to bury nuclear waste, and they have hired folklorists to try to come up with warning-myths that would keep people away from trying to figure out what's buried in these places. How can you keep people away for 10,000 years? They have to come up with something that is so horrendous that people won't go on vision quests, or try to seek treasure in those places just because they're so forbidden.

Right, I know this one. “This is not a place of honor. No great deed is commemorated here. What is here is abhorrent to us.”

You really have to emphasize the danger. But you can't overemphasize it, because then people will decide to go! We have risk-taking genes. So it is really quite an interesting problem trying to come up with an effective warning for life and death survival that can last.

What we’re really talking about, in some ways, is how you encode important information in a way that is going to last for a really long time.

There does seem to be a general limit of three generations. The grandparents experience something or know something they tell their children, and either the parents or the grandparents tell the grandchildren, and then it doesn't get perpetuated after the grandparents die. This was first noticed with the Holocaust, and why people are so worried about the truth of it starting to disappear. You have to get past that three generation limit.

The story has to be exciting enough so that it doesn't just seem old fashioned or out of date. It has to somehow have a timeless quality to it, and it's an interesting problem for human survival.

What’s next for you?

My editor and I are thinking about writing an ancient animal bestiary. I really love animals. I’d love to look at interesting things that people said about animals in antiquity, and whether those stories contain accurate insights and perspectives that have now been shown by science.

Sounds like it’ll be an interesting project. Adrienne, thanks so much for coming on.

It's been great talking with you.

Adrienne Mayor is a folklorist, classicist and historian of (very early) science at Stanford University. Her previous books include Gods and Robots, The First Fossil Hunters and Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Her latest book, Mythopedia: A Brief Compendium of Natural History Lore, is out now. You can follow her on Bluesky.

This has been Heat Death. We're entirely reader-supported independent media. If you like what we do here, feel free to subscribe or leave us a tip.

But while we're growing, the single most helpful thing you can do is send it to someone you think will like it or post it on your favorite social with a nice note. We are, above all, a word-of-mouth operation.

Member discussion