Stone Texts

Drive. Head out of Texas’ urban heart and west along I-10, down off the plateau of the caprock to where the gaps between towns fill hours, till the land is pitilessly flat and remorselessly dry. At the oasis town of Balmorhea, turn south and watch the land turn suddenly half-lush, like the pugnacious greenery of the drier parts of the Mediterranean.

Keep driving. Someplace past Marfa it looms out above you, a landscape that is at once familiar and surreal. The blacktop passes across a land where the dimensions seem stretched out. Great ships of mesas sail seas of desert. Drive past island outcroppings of boulders, toward the mountains that loom on the horizon, lording over the landscape while somehow never getting any closer.

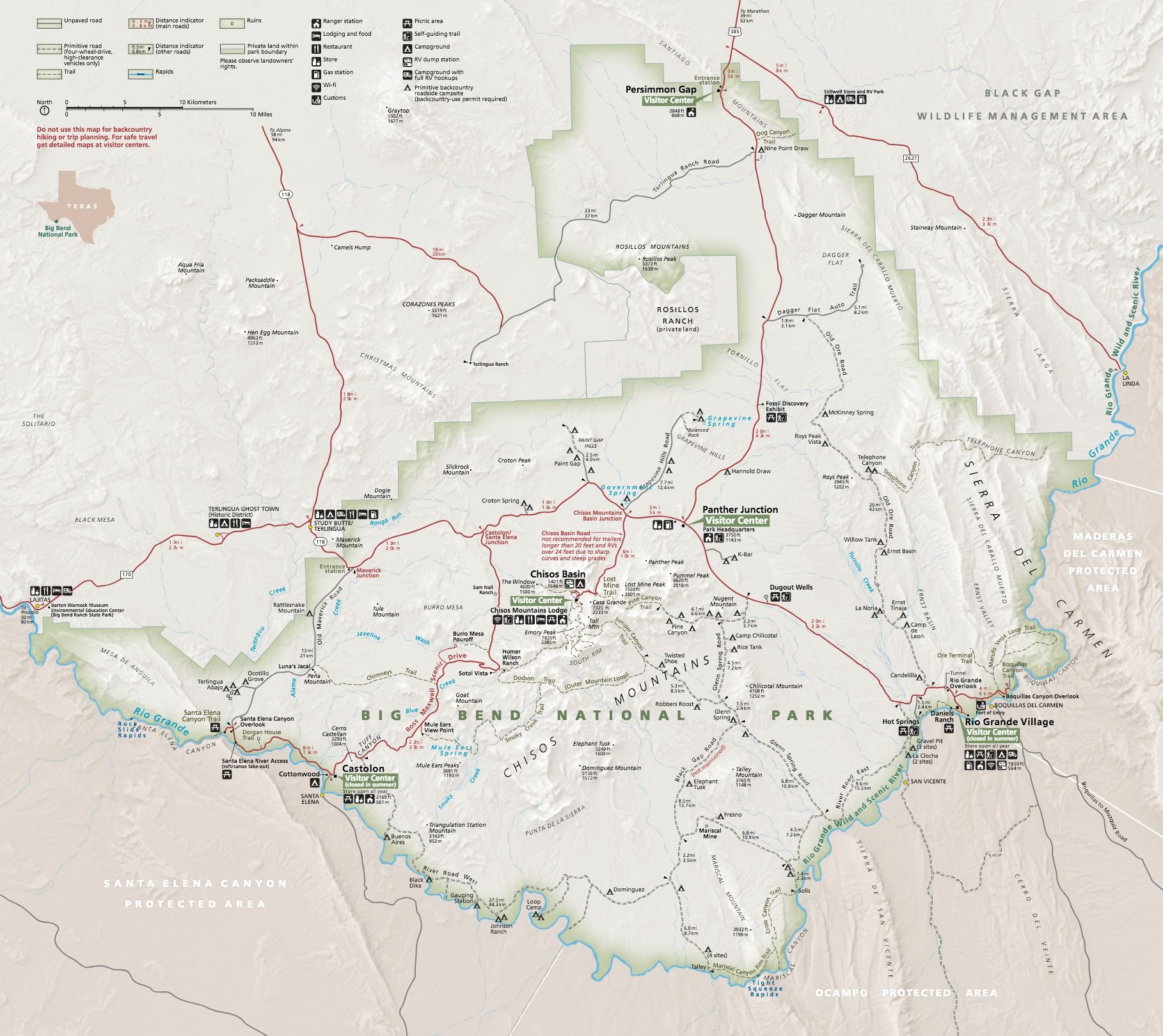

Until, at last, you arrive in the Big Bend National Park, on the edge of two countries — and also, at the same time, a peninsula jutting out into a vast gulf of history.

Saul here. Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that serves as your text-based time machine.

When we first visited the Big Bend as kids, we were both stunned by the power of its landscapes. Slot canyons fluting through narrow sandstone. Mesas standing in lonely towers above the Rio Grande. The mile-high walls of Santa Elena Canyon, their skirts decorated with house-sized boulders that had crashed from the cliffs above; and the mountains of sand piled up along the walls of Boquillas Canyon. And looming above it all, the forbidding heights of the Chisos Mountains, where a forest of lush pines and bubbling creeks nestles in the bowl of a dead supervolcano.

At 15, riding into the park on State Highway 118 in the back of our parents’ Honda Odyssey, I felt a superstitious awe of the place, a land whose features seemed carved out by a living force , beside which any human effort or lifespan faded into insignificance.

Having read Asher’s latest, “Stone Texts,” I feel that way again. At some point, the scale and impact of natural change becomes frankly supernatural, and in the Big Bend the unceasing work of erosion has ground on across unfathomable oceans of time — a scope of change and totality of reinvention that looms above our world and works like a pitiless, unseeing god.

And in the holes and hollows that yesterday’s change has left behind, life shelters and builds, rising while it can, retreating when it must, harnessing the energy from a baking sun to make it one more day — above an earth that quivers always with dangerous life.

It’s Heat Death. Stay with us.

Deep Time In The Big Bend

Consider, for a moment, the passage of time. A human lifespan—if that human is very lucky—is about a hundred years. Two such lifespans encompass the history of Texas as a state, and three the lifespan of the United States as an independent country; ten incredibly long-lived humans, one after another, make nearly a thousand years.

The earliest known fossils from the Big Bend date from 125 million years ago. It is a depth of time that is difficult to grasp; time enough for mountains to rise and oceans to drain, for the landscapes we think of as static to shift and flow like water.

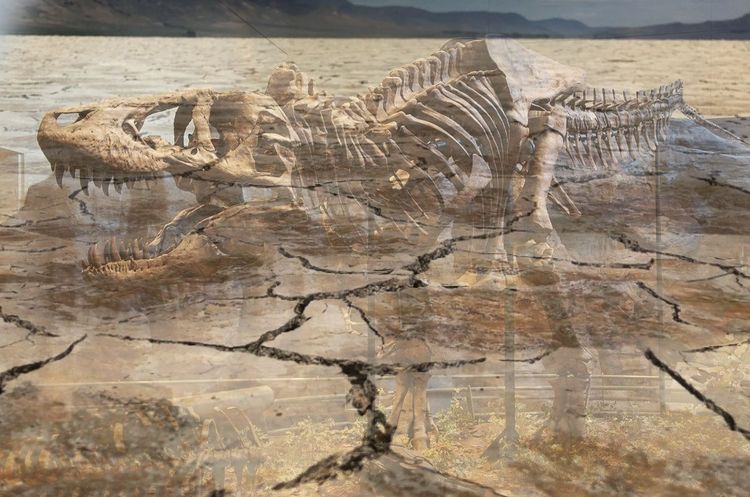

As the land changes over time, everything that lives on it changes, too. We call that process evolution and study its remains through the field of paleontology. Fossils are thus one of many clues about how ecosystems change across the vast abysses of time. In the 125 million years since the first fossils in the park were laid down, enough time has passed for an ocean to become a desert, with many stops and reversals along the way.

And each successive environment has left its trace in pages of rock.

Imagine, then, you are standing in one place amid the red rocks of the desert, with the years racing backward at the rate of one a second. Days pass, and the landscape flattens, greens, fills with blurs of animal and plant life. By the morning of the third day, warm waters are rolling in, advancing and retreating in waves, lapping higher every time.

By the morning of the fifth day, you have traveled back to the Early Cretaceous, 125 million years ago. And you are hundreds of feet underwater.

Now let's play that clock forward again, and watch how the land we know was made.

Shallow Seas

A complex patchwork of white and yellow limestone, siltstones, and chalk, standing in blocks along the walls of mighty canyons and the floors of desert basins.

The Early Cretaceous, 125 million years ago. The center of the North American continent is split by the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow sea that flows from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Gulf of Mexico in the south, 3,000 miles (5,000 km) long and about 1,200 miles (2,000 km) wide, reaching depths of approximately 980 feet (300 m). East of the seaway is the continent of Appalachia, still mysterious to this day; to the west lies the mountainous and geologically active continent of Laramidia.

The land we call Big Bend lies well offshore of Laramidia. There are no ice caps to the North; the water level is hundreds of feet higher than our present, reaching perhaps 300 feet (~ 90 m) at its deepest. The Big Bend is closer to the equator in this epoch, and so the waters are warm and tropical, perhaps fueling vast hurricanes that pummel the distant shorelines.

For millions of years, this Western Interior Seaway sprawls over the interior of what is now the North American continent, rising and falling according to the pulse of tectonic movement and the climatic wobbles of the earth. Some of the layers of sediment it leaves behind will one day be visible on the high walls of canyons like the mighty Santa Elena and Boquillas, and in the high cliffs of the Dead Horse Mountains and the Sierra del Carmen.

But deep within the guts of Laramidia, two vast tectonic plates are grinding together. The seafloor of the Western Interior Seaway has begun to lift, which will one day spell doom for the inland waterway. The ocean is beginning a slow retreat, poured off by the rising land.

By the time of the Boquillas Formation (95-85 million years ago), the future park sits along Laramidia’s continental shelf. Sediments of marine mud and limestone—composed of the shells of billions of plankton—accumulate on the sea bottom.

The hot waters are bad for corals. Instead, the reefs that carpet the sea bottom are beds of 6-foot long rudist clams, their shells clustered with tangles of oyster and mollusk-like bivalves. Tiny fish and crustaceans swarm around the giant clams, darting inside the open shells whenever a shadow passes overhead. Sea urchins and heart urchins make their spiny, blind way around and over the towering mollusks, and crinoids waft feathery arms like the petals of underwater flowers. Here and there, the barnacle-encrusted bones of reptiles poke from beneath the ooze, which harbor bone-worms boring away within in search of remnants of flesh.

Swimming in the water column above these reefs are clouds of fish and crustaceans, supporting a vast food web of everything from sharks to mosasaurs, shark-like lizards with long, fearsome jaws.

Run the clock forward a few million years more and the waters have grown shallower still. The seaway of the Pen Formation (85-82 million years ago) now ripples with the clear, warm waters of a tropical atoll. In this shallower environment, the sunny seas are patrolled by sharks, small mosasaurs like Clidastes, and fish like the giant Xiphactinus, the hungry bulldog tarpon. Spiral-shelled ammonites and invertebrates of the marine shelf creep through the oyster beds. At night, perhaps, deep water predators rise in alien flickers out of the dark: the faint pulsing glow of jellyfish and the fast flashing of squid, journeying up from the depths to hunt for prey. They leave trails as they disturb bioluminescent plankton, colorful smears that flash and slowly die in the gloom.

Time passes. In the Big Bend, the ocean is dying – but the park's pageant of life is only beginning.