The Myths of Antisemitism

Saul here. In the beginning of August 1947, mobs gathered across England and Scotland and attacked their Jewish neighbors.

In Liverpool, mobs painted “Death to All Jews” on a synagogue, uprooted gravestones, burned a factory, and hit roughly 300 Jewish properties. After four men were arrested for vandalism, “Multiple baton charges were required to disperse the crowd,” one historian wrote, and “the unrest had spread to London, Manchester, Birmingham, Hull and Brighton.” There, crowds numbering in the hundreds smashed the windows of synagogues and Jewish-owned shops. Vandals scrawled messages like “Hitler was right.”

It’s eerie to read about the event today, as an American Jew. It looked like the looming pogrom that — we are continually warned — is waiting for us, even in the liberal West: an explosion of rising antisemitism, which Israeli and American politicians and pundits commonly call the “oldest hatred.” An eternal and motiveless malignity that fed a long litany of massacres, political repression, state destruction and the industrial murder of the Holocaust.

But 1947’s riots were different: they had been provoked. Not, to be clear, by those who were attacked — but by a right-wing Jewish movement that had enlisted Britain’s Jews as unwilling pawns in its war in Palestine.

This is Heat Death, the newsletter that never forgets to Never Forget. As I write, the last Israeli hostages have returned from the bombed-out wasteland of Gaza; 2,000 Gazans are returning from Israeli prisons to the shattered remnants of their city-state.

I don’t know if the war is over, or if “over” is even a meaningful word here. But as Gaza’s prisoners and refugees return, they will be joined by outside journalists, and the scale of the destruction — long obscured and easily ignored when only Gazan reporters could show it — will finally be made clear.

It’s worth noting here that — even if the Israeli campaign in Gaza had been as measured and righteous as its propagandists attest — the impact of modern bombs and artillery on a dense city is horrific. In 2017, while embedded with the Philippine Army during a seven-month campaign against ISIS in the southern city of Marawi, I entered a grotesque inversion of civilization: high-rise buildings leaning against each other like half-fallen dominoes, surviving structures blasted from the inside out, the settings for people’s most intimate lives were turned into a backdrop for room-to-room fighting. Marawi — one-tenth Gaza’s size and mostly evacuated during — still seared me. Gaza was and will be almost unimaginably worse. The imagery of apocalyptic devastation coming out from the city will spread in the context of a U.S. administration that has made “antisemitism” the standard it marches under in its attacks on the key underpinnings of the liberal order: diversity, equity, and civil rights.

This is not a new approach. As in so much else, a major pioneer of this weaponization of antisemitism was our home state of Texas, which in 2017 banned state agencies from any association with funds that subscribed to the Boycott, Divest and Sanction movement. This summer, a new state law uses the specter of rising antisemitism to restrict professors from speaking about issues deemed “woke” by Texas’s far-right leadership.

These efforts in Texas and the wider country have not been a narrowly partisan project: they have instead been a joint effort of the Christian right, the Democratic centrists, and much of America’s institutional Jewish leadership. This alliance has sought to fuse two ideas: unconditional support for Israeli policy as a prerequisite of American thought and a warning that unchecked “wokeness” could invite 1947-style antisemitic riots.

Now, as the bombs stop falling, it’s time to re-interrogate that episode and the modern idea of antisemitism — its origins, its role as a kind of heresy within modern Judaism, and the terrible uses to which it’s been put.

And to ask: Do Jews still need this concept? And can we truly afford to keep it?

This is Heat Death. Stay with us.

Heat Death is an entirely reader-supported newsletter, and all proceeds go toward paying guest writers and maintaining our web-hosting.

If you enjoy what we do here, please leave us a tip or sign up: paid subscriptions start at just $2-$5 a month.

Let’s return to the pogroms that swept Britain in 1947, and the question of how they kicked off. I’m relying here on Anonymous Soldiers, Georgetown professor Bruce Hoffman’s history of the right-wing Jewish revolt against the British in Palestine. The star player in Hoffman’s account is the National Military Organization, or Irgun, which split from mainstream Jewish militias in the late 1930s.

In the late 1930s, after provocations like the massacre and expulsion of the ancient Jewish community of Hebron by Arab rioters, Irgun militants carried out some of the Middle East’s first terror bombings, planting nail-bombs in Arab markets that killed dozens. But later, under the more disciplined leadership of future Prime Minister Menachem Begin, the Irgun went to war with the British, who — in an effort to avoid a reprise of the great Palestinian revolt of the late 1930s — had largely cut off Ashkenazi Jewish migration into Palestine.

In an effort to force the British to change that policy, Begin directed a terror campaign against them. There were assassinations, mail bombs, and attacks on police stations. Their destruction of the King David Hotel was the most deadly terrorist bombing in the region until Islamic Jihad blew up the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut almost 40 years later.

But none of these attacks had the effect back home of what the Irgun did next — the coup de grâce on the British Mandate, and the trigger for the riots of August 1947.

In July 1947, three Irgun terrorists, as the British called them — Avshalom Haviv, Meir Nakar, and Yaakov Weiss — sat in the dock awaiting execution, having been captured during a spectacular attack on the prison at Acre that freed 27 Jewish militants.

The British had tried and convicted the three men for their “intent to kill or cause other harm to a large number of people,” which carried the sentence of death. Just after it was handed down, the Irgun kidnapped two British Army sergeants, Clifford Martin and Mervyn Paice. Begin threatened the Mandate: if the British killed Haviv, Nakar, and Weiss, than Martin and Paice would die too.

It was, for the British, an impossible dilemma: cede control over their criminal courts to the Irgun or call the bluff of an organization that had shown no inclination to do so. In the end, the British carried out the sentences. The Irgun men died on the scaffold. And that same day, as Hoffman recalls in Anonymous Soldiers, Irgun operatives went to the basement where Martin and Paice were being held.

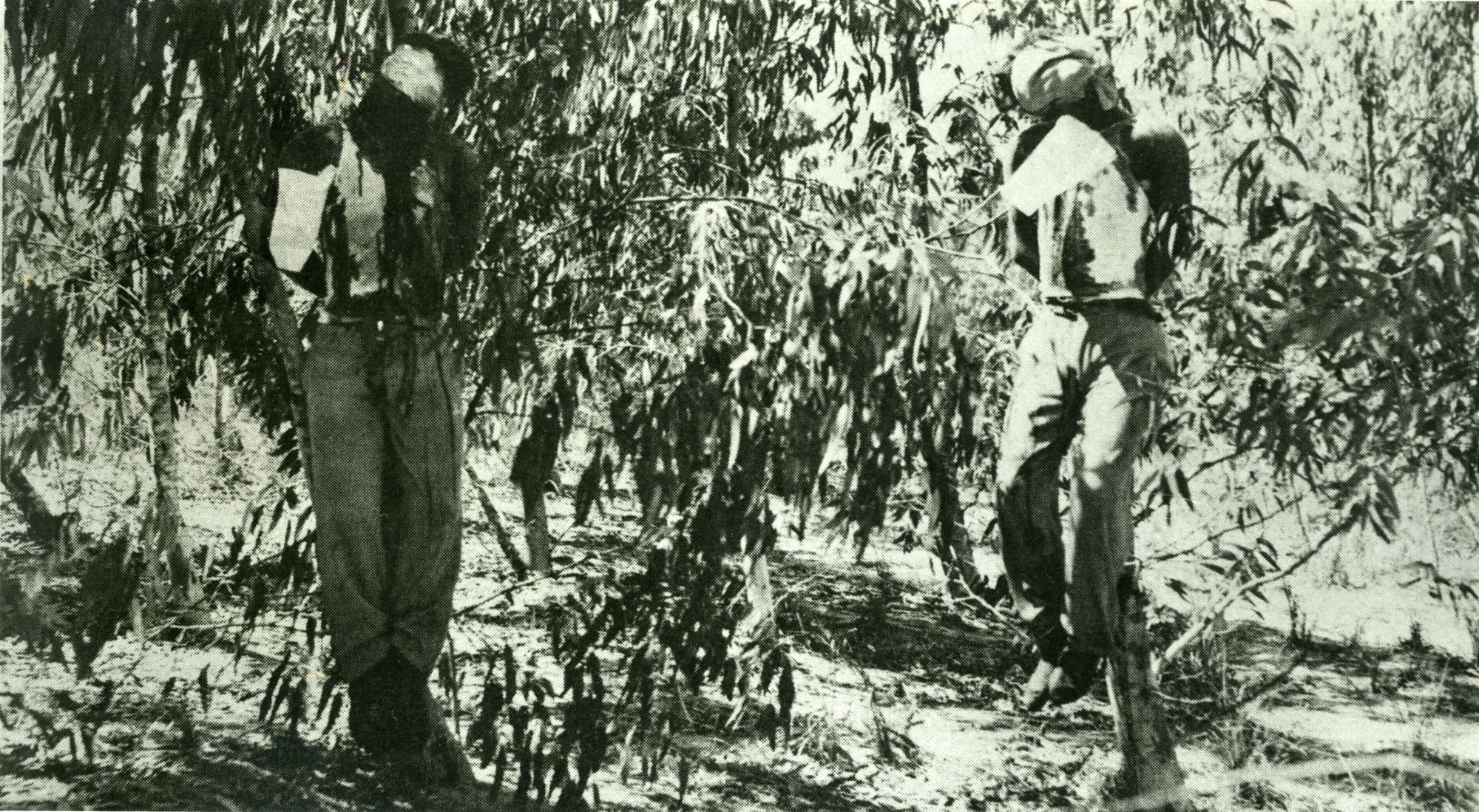

One of the sergeants was pulled from the stifling oubliette, bound, hooded, and placed on a chair. A noose was flung across a roof beam and fastened around his neck. His final request to leave a message was denied, and the chair was kicked from beneath him. The same was done to the other. Their bodies were loaded into a jeep and taken to a eucalyptus grove on the outskirts of Netanya, now a park known as the Sergeants’ Grove.

As a captain of the Royal Engineers cut Martin down, a hidden mine detonated, obliterating his body and injuring the officer.

“This gratuitous act of vengeance,” Hoffman recounts, “was the last straw.” In the days that followed, police and soldiers in Tel Aviv rioted: looting cafés, beating patrons, throwing grenades, and firing on a Jewish-owned bus. British newspapers soon carried photographs of the sergeants’ corpses. The Daily Express called it “medieval barbarism.” The Times of London said it matched “the bestialities practiced by Nazis.”

Then the riots — which we have previously discussed — reached Britain. The Jewish shopkeepers of Northern England, of course, had been no more responsible for the deaths of Martin and Paice than those sergeants had been for the hanging of the Irgun men. But collective punishment had been the shared modus operandi of both Arab and Jewish militants in Palestine throughout the waning days of the Mandate. Now, that logic had boomeranged back into Britain’s imperial center.

Moreover: the riots, however, unjust, were no simple explosion of antisemitism. They were a direct result of actions taken by a small group of Jews who claimed the right to speak and act for the broader diaspora. They were arguably even a marker of the Irgun’s success: they brought disorder to the heart of an empire that prided itself on liberal order and tolerance. They showed Britons their government could not keep order — and told Western Jews that liberalism could not keep them safe.

In the wake of the riots, a party pamphlet warned the British, in fractured English:

We warned you day in and day out, that just as we smashed your whips so would we uproot your gallows — or, if we did not succeed in uprooting them, we would set up next to your gallows, gallows for you.

And we have not yet settled our hanging accounts with you, Nazo-British enslavers.

Hoffman’s book hints at an alternate history. Britain might have set its teeth and stayed the course, redoubling its efforts to crush the Jewish insurgency. The displaced persons’ camps might have become semi-permanent settlements like the Palestinian Arab camps in Jordan and Lebanon would later, feeding desperate young people into the Irgun and its splinters. The Irgun might have undertaken a longer reign of bombings and killings of the sort later carried out by the Irish Republican Army.

None of that happened. By spreading disgust and disorder into the heart of the Empire — by provoking lumpen Brits to riot against fellow Jews — they finally convinced Britain to end the Mandate. Within four months of the riots, Jews and Arabs in Palestine had begun the civil war that culminated in the first Arab-Israeli War, the Jewish ethnic cleansing of their partitioned lands, and the beginnings of the Palestinian diaspora in the camps of Gaza, the West Bank, and beyond. Within a less than a year, Britain had left Palestine entirely.

The Irgun had won. And when I say they won, I mean they eventually won the whole pie. After the failure of the socialist Labor Party to head off the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Menachem Begin became Israel’s first right-wing prime minister. As I write, Benjamin Netanyahu has served five terms as head of Likud, the party Begin had founded.

Israelis now live in the world its right wing made — one in which the notion of danger to Jews justifies anything and everything: attacks on innocents, conquest, and terror abroad. And it is abroad, to the Jewish diaspora, that we must now turn our attention.

If you live in any of the biggest 40 cities in America, you may have seen billboards warning of a new Holocaust. In not-quite-Comic-Sans on a pink-purple field, they say things like:

- “We’re just 75 years since the gas chambers. So no, a billboard calling out Jew hate isn’t an overreaction.”

- “Can a billboard end antisemitism? No. But you’re not a billboard.”

- “Zionism = Jews having a home. If that bothers you, maybe it’s not Zionism you hate.”

Some localized it. In Austin last week, amid the second weekend of the city’s Austin City Limits music festival, two billboards over the city’s main highways invoked the Nova music festival near Gaza, where Hamas killed nearly 400 and took dozens hostage: “They went to a music festival and didn’t come home.”

The campaign’s architect, Archie Gottesman, is the former branding officer for a New York mini-storage chain and the co-lead of JewBelong, one of many 501(c)(3) projects trying to message the Jewish community out of its current crisis. The Austin billboards, she told KXAN, were part of a campaign to build a broad coalition against “Jew hate.”

“Kids went to [Nova] music festival, just like they’re going to the music festival in Austin,” Gottesman said. “And those kids were murdered.”

Before we continue on, I’d like to offer a bit of useful perspective, because the above message has been offered so often in the past two years that it’s easy to forget how bizarre it is. How is dying at a music festival more tragic than doing so with your entire family inthe rubble of an apartment building? Or in a bread line inexplicably shot up by the Israeli occupation? Or while trying to recover the body of your brother shot in that bread line, as a Jewish kid from Chicago, raised on Zionist propaganda, fired up on the need to “protect” the Jewish people and trained as an Israeli sniper, casually shoots you down before wondering to an interviewer “what was so important about that corpse?”

It is hard to shake the idea that the thing that is morally sacrosanct about dying at a music festival, as Omar el Akkad suggests in One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, is that — unlike people in refugee camps and tents and cities with Arab names — people who attend music festivals aren’t supposed to die. They are people, in other words, like us. Or to say it shorter: they are people. A category that, in this construction, is not inclusive, but exclusive. It is also, I think it’s important to note, flatly blasphemous in Jewish terms. Our tradition is clear: every life is of infinite value. Every human is made in the image of God. In Jewish ethics, you cannot weigh life against life.

So back, then, to Gottesman, who on her LinkedIn calls herself Judaism’s “Co-Chief Rebrander,” quoting a “wise rabbi” who said, “Judaism is a great product, but the marketing sucks.” As easy as it is to dunk on her, her campaign is actually a useful case study in the ways that the Jewish mainstream has gone astray in its response to Gaza. And the main root of that, I’d argue, is its commitment to the idea of antisemitism as an enduring force that transcends time and space. Or, as Gottesman responded when a reporter asked her whether the billboard campaign might inspire blowback, ““Antisemitism is this growing horror that people don’t need reasons for,” she said. “That hate will grow on its own, and it is not because of a billboard.”

The hate will grow on its own.

You hear that quite a lot these days: a portrayal of antisemitism as an invasive weed that seeds itself in gardens of the mind, and must be ruthlessly pulled up, bearing fruit in the Holocaust and October 7, fertilized by (of course) campus protests. The Free Press founder Bari Weiss called it “the hatred that never dies … the oldest hatred.” Deborah Lipstadt, the historian and Biden’s envoy on antisemitism, calling it “a virus without a cure.”

Last year, President Joe Biden himself warned at Holocaust Remembrance Day that hatred for Jews didn’t begin or end with the Holocaust, that it “continues to lie deep in the hearts of too many people in the world, and it requires our continued vigilance and outspokenness … That hatred was brought to life on October 7th.”

Netanyahu himself laid out the standard case when he addressed Congress last summer. Asked about campus protests calling for Palestinian freedom, he told lawmakers:

[Antisemitism] is the world’s oldest hatred. For centuries, massacres of Jews were always preceded by wild accusations — that we poisoned wells, spread plagues, used the blood of children for matzos. Those preposterous lies led to persecution, mass murder, and ultimately the Holocaust.

Now, just as malicious lies were leveled for centuries at the Jewish people, malicious lies are being leveled at the Jewish state.

No, no. Don’t applaud. Listen.

As someone who grew up Orthodox and for whom Judaism is a vital part of my life, I would like to point something out to all of these luminaries: this is so incoherent as to be not just bad thought but — as we are starting to see now in the collapse of worldwide support for Israel — bad propaganda.

But let’s concern ourselves here with why it is lazy and misleading thought. As Claude Levi-Strauss taught, myth is the structure of society — the trellis around which our lived experience grows. They are lenses that filter the chaos of existence. So we should be careful that our trellises actually shape our thoughts in a useful way; that our lenses are clear.

And antisemitism is a flatly useless lens to investigate the Hamas and Qassam massacres on October 7, which fall much more squarely into a different realm: one the above speakers and people like them continually elide. The realm of politics.

So let’s adopt, for a moment, a political — even historical — lens. Consider the military wing of Hamas in 2023, a group that rules over a city-state in a state of perpetual siege, in a strange mutually-agreed-upon relationship of tit-for-tat atrocity with the Israeli government. Because it’s 2023, they exist in a geopolitical context where Israel is allowing right-wing settlers to colonize the West Bank, on the brink of signing security pacts with Arab monarchies that cut the Palestinians out, and holds thousands of Palestinians of all stripes sit in prisons. Where, crucially, hostage transfers are the only viable way of getting them out.

In this context, leaders like Ismail Haniyeh or Yahya Sinwar — men who had spent much of their lives in those Israeli prisons, spoke Hebrew, and who knew their enemy very well — noticed that Israel had gotten complacent. Guards had disappeared from the walls to cover for land grabs in the West Bank. He conceived of a brutal attack that will upend the table, creating a period of chaos in which the situation might — might — be reset. And on October 7, Hamas and Qassam fighters launched what is in effect a rebellion against their onetime semi-partners in the Israeli state.

The fact that part of this rebellion was a massacre and cold-blooded murder of innocents doesn’t undermine the fact that it was — described coldly — a political act, with a political calculus. As Hoffman notes in Anonymous Soldiers about the Irgun campaign against the British — and as Al Qaeda clearly understood before 9/11 — part of the goal of terrorism, particularly against an occupying force, is to the bargain the authorities make with their subjects: that they can keep them safe if they obey, and punish them if they don’t.

In the smoking ruins of the King David Hotel, the Marine barracks in Beirut, the Twin Towers, or Kibbutz Be’eri, terrorists offered a single political statement that cut to the heart of the regime’s legitimacy: No, you can’t.

They said in effect — as the Irgun argued to the British after the lynching of Paice and Martin — You cannot stop us. And beyond that: You are the architect of this disorder. And for any putatively liberal occupier or empire — Britain, America, Israel — there’s an added bit of counter-imperial jujitsu: Now, in reacting to this outrage, you must become like us, and everyone will see that you were never anything else. Just as we always said.

So. Let’s allow that the fighters who killed almost a thousand civilians probably hated the Jews they hunted down. Is that hatred particularly useful in understanding what they did, and what to do about it? No more so, I’d say, than “They hate us for our freedoms” helped Americans understand Al Qaeda, and what to do about them. Both lines of thought led instead straight into atrocity that beggared the scale of the initial attack, as well as badly corroding the legitimacy of the empires in question.

But you don’t need to take my word for it. Influential early Zionists didn’t think that antisemitism was the right way to think about Arab opposition to their project either. When Ze’ev Jabotinsky, intellectual godfather of the Israeli right, argyed for greater Jewish colonization In the seminal 1922 essay, “The Iron Wall” he also offered a clear-eyed assessment of Palestinian opposition. The Arabs, he wrote, did not oppose his desired migration out of ignorance or prejudice. They did so because they recognized it as a threat.

Every native population, civilised or not, regards its lands as its national home, of which it is the sole master, and it wants to retain that mastery always; it will refuse to admit not only new masters but even new partners or collaborators.

The native population of Palestine, confronted by tens of thousands of Ashkenazi colonists, he writes later,

feel at least the same instinctive jealous love of Palestine as the old Aztecs felt for ancient Mexico, and the Sioux for their rolling prairies.

To imagine, as our Arabophiles do, that they will voluntarily consent to the realisation of Zionism in return for the moral and material conveniences which the Jewish colonist brings with him, is a childish notion, which has at bottom a kind of contempt for the Arab people; it means that they despise the Arab race, which they regard as a corrupt mob that can be bought and sold, and are willing to give up their fatherland for a good railway system.

And yet antisemitism as a lens for the conflict persists.

I’d argue that’s emblematic of a larger ontological mistake made by American Jewry and its defenders. Namely, that there’s a single deep-rooted, universal thing called “antisemitism” that exists at all.

The broad claim around antisemitism made by people like Joe Biden, Bari Weiss and Bibi Netanyahu — as well as countless Jewish communal figures across America — these past two years is this: that a line of continuity runs between October 7 and the SS death squads that machine-gunned Jewish families in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe.That indeed, both are symptoms of a primordial, transhistorical hatred, an incurable virus flaring up no matter how history changes.

This account is more or less dogma in the Atlanta Jewish community I was raised in (where, incidentally, Deborah Lipstadt — the Emory professor and future antisemitism czar — was a member.) It argues that history is like a long series of flareups of the auto-immune civilizational disease called antisemitism. The Assyrian destruction of the Kingdom of Israel? Antisemitism. The Babylonian sack of Jerusalem? Antisemitism. The repressions of the Seleucids that provoked the Maccabee revolt? The Roman destruction of rebel Jerusalem, and the still more total devastation of the Galilee after a rebellion? The drive-by horrors of the Crusades? The expulsions from England, France, Portugal, and Spain? The Cossack massacres? The Russian pogroms? The Holocaust? October 7? All are black pearls on a terrible necklace called “the oldest hatred.”

But this is theology masquerading as history. It comes from an illusion cast by overlapping facts: (1) Jews have spent thousands of years as a diasporic people living among others; (2) we are extremely literate; and (3) our historiography turns on the idea of cyclical devastation and renewal — the inevitable destruction when we fail to keep God’s laws, and the inevitable resurrection when chastened, we return to them.

When Jews say at the Passover Seder, “In every generation they have risen against us to destroy us,” that line comes out of this tradition, which offers a religious explanation for why the God’s Chosen People come under attack in the communities where they live. In this view, the non-Jewish nations who harry the Jews are like the bumpers on the outsides of a bowling lane — keeping us in line.

But over the last century, as Jews became far more secular and the old heder version of historiography lost its grip, this idea morphed. In the work of Zionist historians, particularly in the wake of the Holocaust, the agent in the Jews’ long string of tragedies ceased to be God, and became the antisemite.

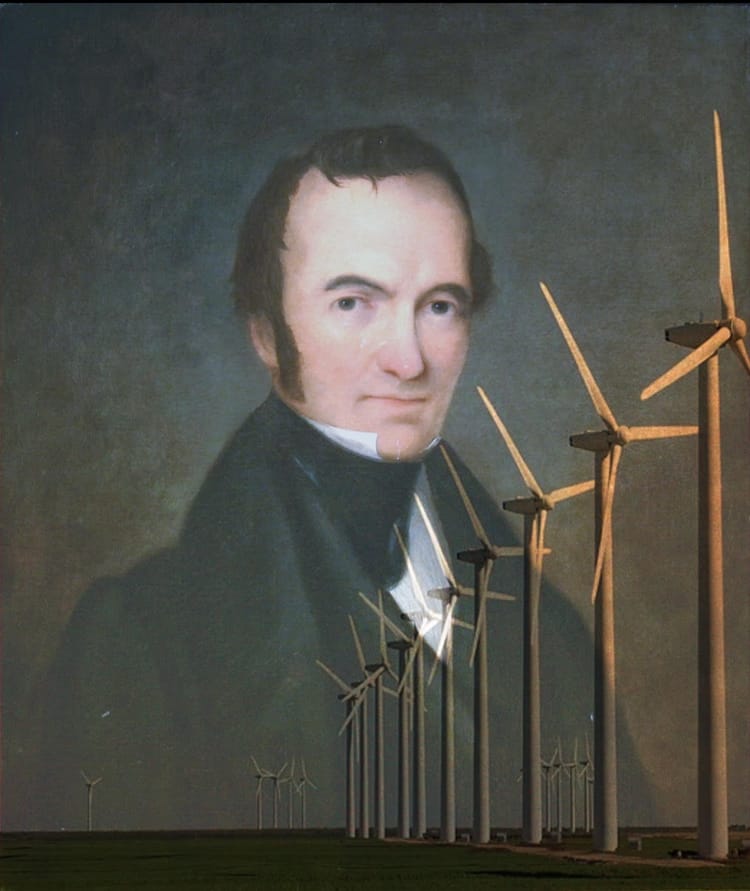

One of the most prominent intellectuals in this new syncretism was Bentzion Netanyahu, the esteemed father of Israel’s current prime minister. Netanyahu père was a scholar of the Jews of Europe, especially the Spanish Inquisition and the catastrophic expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Jews from Iberia. He was also a luminary of the right-wing Revisionists, a group which argued that Zionists should conquer a state whose frontiers should expand as far as they could push them. (He was briefly secretary to Jabotinsky, and during the years of Jewish terror and revolt against the British Mandate, he led the New Zionist Organization of America, which functioned as something like the Irgun’s American political arm.)

In The Origins of the Inquisition in Fifteenth Century Spain, the elder Netanyahu argued that antisemitism was racial, not religious, and traced the “Jew hatred” that led to the expulsion of Spain and Portugal’s Jews back to ancient Egypt. In an interview with the New Yorker’s David Remnick, he claimed the Holocaust differed from earlier catastrophes only in scale. Jewish history, Netanyahu told Remnick, was “a history of holocausts.” He often argued that, given the chance, Israeli Arabs would launch the next one.

But these are very different historical cases! In the first bucket, we have the repeated destructions of independent Hebrew states — events that follow a fairly consistent and disastrous ancient pattern: a group of radicals, fired up on the idea that God or an imperial neighbor will protect them, rebel against the large, ruthless empire to which they had been vassals or subjects. That belongs to geopolitics, not to any enduring cross-cultural hatred of Jews. Plenty of peoples on the borders of Rome, Babylon and Assyria suffered the same or worse, with the sole distinction that they did not leave us a historical record that became the center of the Western canon.

The Hellenistic and medieval race riots, meanwhile, can be seen as something quite horribly common: inter-communal violence between diasporic peoples and their host populations. These are hardly unique to the Jewish experience. Greeks, Armenians, or Chinese diaspora communities could tell similar stories across their own long histories and arcs of settlement. In fact, while inter-communal violence has largely been something Jews suffered as a convenient minority, we’ve gotten our licks in as well: The Second Roman-Jewish War, the Kittos War, began with mass killings of non-Jews in communities across the Mediterranean by their Jewish neighbors.

But what about the Christians, I hear you ask? Christian antisemitism is deep-rooted. But it’s political as well: the result of a brutal divorce in the early centuries of the Common Era by which Christians defined their own religion against that of the emerging institutions of Rabbinic Judaism.

That textual and religious antisemitism, however, also blends with more complicated forms of communal tension. One thing that made the Crusades or the Cossack uprisings of early-modern Ukraine so particularly vicious was the peculiar social role Jews often played in those societies: favored administrators for a repressive Christian elite. Does that excuse the killing of tens of thousands of my ancestors’ cousins in Eastern Europe? Of course not. (Though I’d argue the fact that I have to reflexively genuflect in this way is part of the problem with how we talk about this stuff now). What it does is situate the violence in a recognizable social and political context — not as an eruption of timeless evil, but as the revenge of subjects against an elite class that sometimes included Jews. Sometimes, in fact, for that very purpose.

In fact, what we now call antisemitism — organized pogroms, nationalist ideology, and state complicity — was something that arose quite recently, in the 19th century. While you still had occasional outbreaks of religiously-inflected local violence, the broader trend was toward something more recognizably modern: the politicization of antisemitism as a tool of illiberal nationalism. Where Jews had once been targets because of their role as a town’s designated banker, tax collector, or overseer for absentee landlords, they were now targets because of what they symbolized — and what they allowed new political actors to define themselves against. Rising nationalist movements across Europe and the Levant — from Syria to Spain, Germany to France — cast Jews as a convenient “other.” Canny rulers and demagogues, attempting to revive fractured or decaying states, defined their new regimes against an internal enemy. And so Jews became the dark mirror by which non-Jewish Spaniards, Frenchmen, Germans, Russians, or Iraqis could know themselves — and by which new parties could seize power.

It’s significant, then, that the 1879 coinage of the term antisemite came from a right-wing German nationalist party — a group that defined Jews as the mystical internal enemy holding a putative German nation down. That word, and the politics behind it, preceded by only a few years the wave of pogroms that tore through Jewish communities in Eastern Europe after the assassination of the liberal Czar Alexander II. His successor, Alexander III, twined antisemitism and Russian nationalism to shore up an increasingly reactionary state — ushering in decades of state-sanctioned mass violence that drove millions of Jews from the Russian Empire. (It was also, by the way, in Imperial Russia that antisemites concocted The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which would go on to trouble Jews to this day.)

Soon after, France — the first modern state to emancipate its Jews — was split by a culture war over the Jewish military officer Alfred Dreyfus, who was flagrantly and incompetently framed for espionage by a right-wing movement that saw antisemitism as a tool for national revival.

For millions of Eastern and Central European Jews in the late 19th century, the pogroms and the Dreyfus Affair confirmed that Europe’s liberal promises had collapsed. But that collapse mattered precisely because liberalism’s promise had once been real. Jewish liberalism in Europe wasn’t naïve; it was a centuries-long experiment in growing coexistence. It had built schools, newspapers, parliaments, and philosophies — entire worlds of thought that made Jewish life within modern Europe not just possible but flourishing.

In its attempted-wholesale destruction of European Jewry, the Nazis annihilated those experiments. In the ashes of that world, only Zionism survived. And the story it told — of repeated atrocities echoing down through history, where safety that was only possible through military power and sovereignty — became the moral operating system of the modern Jewish world.

What this leaves out is something important: everything else.

Jewish history is punctuated by tragedy — but that’s history for you. Jews spread across the world, and we have been around a long time: in every generation, in a community that eventually spread from Iberia to India and China, something bad is bound to happen somewhere. And focusing on those tragic eruptions leaves out millennia of not just survival. It leaves out the moments where we thrived.

It doesn’t just leave those moments out, in fact — it negates them. That’s the term that was adopted by Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg, better known as Ahad Ha’am, the seminal Zionist thinker of the late Russian Empire, in “The Negation of the Diaspora." Ha’am, a Jewish nationalist, believed that Jews needed a sovereign state to redeem the terrible condition that centuries of diaspora had left them in — poor, humiliated, tasteless, passive — and that only the “fixed center” of a Jewish state could weld them back together.

Or, as Russian-Jewish Zionist A.D. Gordon summed up:

[W]e are a parasitic people. We have no roots in the soil, there is no ground beneath our feet. And we are parasites not only in an economic sense, but in spirit, in thought, in poetry, in literature, and in our virtues, our ideals, our higher human aspirations. Every alien movement sweeps us along, every wind in the world carries us. We in ourselves are almost non-existent, so of course we are nothing in the eyes of other people either.

Decades later, in Jerusalem, historian Joseph Klausner declared:

The last twenty years have demonstrated that Herzl, Nordau and Jabotinsky were right when they maintained that either we eliminate the diaspora or the diaspora will eliminate us.

That philosophy of naked contempt for the diaspora is what Asher and I were raised with — which is strange, because we come from America, home of perhaps the strongest and most self-assured Jewish diasporic community in history. And yet that philosophy has made for strange bedfellows. In 2007, I covered a rally in San Antonio, Texas, where evangelicals gave the Israeli state $8.5 million to foster, among other things, Jewish migration into the settlements. The rally was the brainchild of John Hagee, pastor of Cornerstone Church and father of the Christian right’s Zionist revival — a man who believes that the Holocaust was part of God’s plan to get Jews into Israel, where they could play their appointed role in bringing about Christ’s return, their own decimation, and the conversion of the few survivors.

In attendance was then-Israeli ambassador Daniel Ayalon, who told the crowd they were helping with a sacred work:

Within the last 50 years, we have gathered in the Jews from the North, from the East, from the South. Now, with the help of our Christian allies, we are going to finish this job and bring the Jews from the West as well.

Whether Ayalon meant it or not hardly matters. True, he was playing to an audience that he knew wanted to see the Jews returned to the Holy Land. But I was raised on similarly messianic messaging — that for American Jews, our only true home was Israel, where we could finally be “safe.” When I was eighteen, funds from our community sent me to Israel on a Birthright trip, where one of the few mandatory stops was the Holocaust Museum of Jerusalem: the negation writ in concrete and glass. The building is a long triangular prism crisscrossed by a serpentine path through horror that gives out, finally, into a jaw-dropping view of Jerusalem.

As though to say: we have emerged from the world of Holocaust, and this is why.

The trouble was, the idea doesn’t make sense on its own terms. A strict reading of Jewish scripture shows that independent statehood is fraught and fragile. Kings and princes are often disastrously bad — even purportedly great ones like David and Solomon — and the empires we have relied on to protect us are often faithless friends.

I don’t fault the early Zionists of the Russian Empire for their reading of history. They were living through the early stages of what would become the utter destruction of their society — the curdling of the hopes of Russian liberalism during a period of civil disorder that is basically unthinkable, the revelation of how much parts of France still hated them in the Dreyfus scandal. They correctly diagnosed that for European Jews, the need for a refuge that could not refuse them — where they controlled the borders — would become life-or-death, especially after Britain and America closed their doors to Jews fleeing a Nazis regime that was ramping up into a death campaign. In the same way, for Palestinian Arabs, Israel’s refusal to allow them control over their own borders has left millions in terrible limbo across the Middle East.

But the disease of presentism is hard to avoid, and the early Zionists could not — because they were living through it — see how historically contingent their experience of antisemitism was. The deteriorating conditions of the Pale of Settlement blinded them, I think, to a much older tradition: that in a world where tragedy is inevitable, the diaspora is the Jews’ strength.

That’s the idea poignantly explained by Don Isaac Arbabanel, the great 15th-century Sefardi commentator — a refugee of the very Iberian expulsions that Bentzion Netanyahu insisted were the signature fact of Jewish history, and which so necessitated a heavily armed state.

Arbabanel didn’t disagree with the first part exactly. But writing from a comfortable exile in Venice, he took issue with those who argued that God had dispersed the Jews to annihilate them. Instead, he wrote, when Jews are concentrated, they are easy to destroy.

Indeed, our sages believed that God showed special kindness to Israel by scattering them among the peoples. The Trojans, a mighty nation, were totally destroyed by the Greeks because there they were in one place.

But the Jews, however decimated, have always managed to survive and find refuge. The king of England wiped out the Jews in his kingdom as has the king of France in our own time. Had the Jews been in any one place alone, not one Jew would have survived. But the Almighty promised us, “When they are in the land of their enemies, I will not reject them, or spurn them so as to destroy them utterly (Leviticus 26:44).” Dispersion was thus a great kindness ensuring our survival and deliverance.

That’s an idea today’s American Zionists, by their continued presence on these shores, implicitly accept. But they have also forgotten, perhaps, why our immigrant ancestors were so often somewhere between outright communists and New Deal liberals: because for Jews, socialism and liberalism were the philosophies most tied up with our own liberation. They were not solely starry-eyed idealists. They were making a direct political calculation of their own: that if antisemitism is not a transhistorical demon, but a specific feature of populist nationalism, then it follows that Jews can best live in peace — and thrive — only through the battle for the rights of all peoples, together, in a liberal or at least anti-racist polity. As the Jews of the leftist-nationalist Bund party in Poland used to say, before their destruction by the Nazis, “for your freedom and ours.”

In The No-State Solution, Rabbi Daniel Boyarin argues for the Jewish diaspora as a kind of crosscutting, transnational frontier — a matrix that connects every Jew in discourse with non-Jewish thought, food, and people, creating a great engine of remixing and recapitulation that has thrown up masterworks like the Tanakh and Babylonian Talmud and, for lack of a better phrase, much of what we now call Western culture.

I don’t mean to be pollyannaish about this: things are starting to get bad. The right wing in the West is now split between neoconservative and antisemitic factions, and while the neocons still hold power, the future seems, for now, to belong to the young antisemites. Left-wing terrorism is still rare, but a disproportionate number of recent attacks — generally by white Americans — have targeted Zionist Jews in the name of Palestine.

But these are, I believe, political problems. And we need to face them clear-eyed. And from a simple political perspective, the fact that for decades the U.S. government and American Jewish establishment have consistently echoed Israeli state hasbara — that our, communal leaders, even heads of onetime liberal bastions like the Anti-Defamation League affirm publicly that Netanyahu, whatever his flaws, runs “the Jewish state,” and that criticism of that state’s fundamentals is inseparable from the disease of antisemitism — risks pushing the vast mass of Americans of no particular ideology beyond a horror beyond what is happening in Gaza into the arms of antisemites.

It makes it coherent to say, as so many canny neo-Nazis online are saying, that if anti-antisemitism and liberalism brought you this: well, what good is it? If Netanyahu speaks for the Jews, and the Jews affirm him, then why aren’t the Jews, in fact, a part of our misfortune?

I want to offer another vision of a way forward, which is, again, an old vision — the muscular left-liberalism that American Jews once near-universally, and still overwhelmingly, affirm. And I want to do that by pointing back: to a story that is one of the pillars of both political Zionism and the eternal antisemitism myth.

That case is the Dreyfus trial, when the show-trial of an innocent Jewish officer by a conspiracy of antisemitic French nationalists convinced Zionist leaders like Theodore Herzl — following the case from Vienna — that Jews had no secure place outside the Jewish state. That’s the version of the story I learned in Hebrew school, in which Dreyfus’ unhappy fate is one more stepping-stone on the inevitable road to Israel.

But Herzl died in 1904, before the story ended. Even before his death, he might have noticed that in France, outrage over the affair brought together a broad popular front of liberals and socialists to fight for Dreyfus’ freedom, and for the separation of Church and State. In 1905, the French left won passage of a law locking religion out of public life. Antisemitism burned on in the French Right — but until the Nazis took Paris, the Republic belonged to the Dreyfusards.

And when the Holocaust came to France, French Jews — protected by their neighbors and the vestiges of a strong state — largely survived. As many as 90 percent of the Jews of Poland were wiped out; by contrast, 75 percent of French Jews lived.

And Dreyfus? In 1906 he was reinstated into the army at a higher rank than the one he had when first imprisoned (the army giving him credit, as it were, for time served). He survived an assassination attempt by a right-wing zealot; served as an artillery officer at Verdun; was incorporated into the Legion of Honor, France's highest civilian and military order. He retired a colonel, and when he died in 1935, his hearse cut through Bastille Day throngs to bear him to the cemetery at Montparnasse, final home of Baudelaire and future resting place of Sartre. At his death, he was revered as a national figure around whose cause the very Republic had been remade.

Let's linger here at Dreyfus' grave for a second, as the old war hero is laid to rest with honors, and imagine another world that might have come into being. Where to be Jewish in Europe would mean roughly what it has in America, which is to say, a place where one can be proudly a Jew, and proudly French, and where the tension between those identities — real, often painful — was nevertheless productive. A powerful force of human flourishing.

Because of the sheer, grinding horror of what would come next — the packing into ghettos; the grey deaths in the camps — it's easy to fall into the belief that it was inevitable. That it is inevitable. The catastrophe in which the heart was ripped out of the Jewish world of Eastern and Central Europe sits on the weft of historical memory like a lead weight, deforming everything around it, projecting an awful inevitability; imbuing those who were most pessimistic with an air of prophecy. Empowering those who are pessimistic now.

But as we sit by this graveside in 1935, let's try to imagine two worlds in flickering superposition: the one which was, and the one which might have been. Forget, for a second, what actually happened; let it become as insubstantial as a dream, however much some might will it. Imagine a world in which the future is not known, because it forks ahead on too many roads.

And hold that sense of contingency — of a future on which dark clouds gather but which is still unmade — in your mind as you face the present. Imagine, please, that this, too, is our homeland. Imagine we can win.

This has been Heat Death. We're entirely reader-supported independent media. If you like what we do here, feel free to subscribe: paid memberships are just $2 t0 $5 a month. (Or you can always leave us a tip.)

But while we're growing, the single most helpful thing you can do is send it to someone you think will like it or post it on your favorite social with a nice note. We are, above all, a word-of-mouth operation.

We'll be back soon with more musings on past, future, and all the crises in between. Until next time.

Member discussion