This is Not A Dinosaur

Welcome to the inaugural issue of Heat Death, where growth and decay are the order of the day.

Early May finds the Brothers Elbein emerging from a long winter slump. Asher had a bunch of pieces come out at the end of April—a piece on the doomed city of Cahokia for the New York Times, a piece on the rise and fall of the Texas ostrich ranching industry for Texas Monthly—and has been busy working on various projects that aren’t quite ready to share yet. Saul is recently returned from Armenia, where he was reporting on the recent drone war; he has a piece out this week in Mongabay on what the future holds for cities like Austin, Dubai, and Cairo: booming dryland cities outstripping their water supplies.

First, we'd like to say, from the bottoms of our hearts: thank you. There are a lot of things to read and a lot of ways you can spend your limited attention, and we’re very grateful that you’ve chosen to spend it with us. What we are going to do here is lay out a proposed newsletter, this time built around the theme of taxonomy: how human-created categories intersect with an extremely messy world.

At this point, you're our patrons. We’re building this plane as we fly it; we want to hear from you about what we’re doing, and how we’re doing it. If you’ve got thoughts about what we’re doing here—if there are ideas we throw out you want to know more about, or things you think we missed—let us know. (And let us know if we can publish any responses.)

Now, without further ado:

WHEN IS A DINOSAUR NOT A DINOSAUR

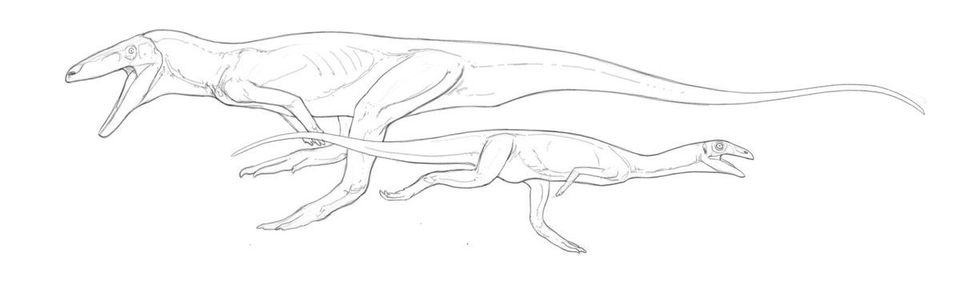

Take a look at the dinosaur-looking creatures above. They have been known to paleontology for decades — and a problem ever since. Poposaurus (left) and Shuvosaurus (right) look classically dinosaurian: bipedal, lithe, forelimbs held away from the ground, long necks counterbalanced by longer tails. Both resemble early predatory dinosaurs, and have been described as such by various people at various times.

Nonetheless, certain anatomical markers in their bones mark them as different: They have subtleties in the shape of their pubic bone; anomalies in the sacral vertebrae. These two animals do not belong to the great and majestic tribe that we call dinosaurs, but to a related family, the Pseudosuchia (“false crocodilians”) which contains every animal more closely related to modern crocodiles than birds.

Which is to say: doesn’t matter that they look like dinosaurs, and probably lived rather like the dinosaurs of the time, which they closely resembled. Anatomically and biologically, they’re less dinosaurs than a sparrow is. Yet they have an essentially dinosaurian sort of quality, which, it turns out, is not actually uniquely dinosaurian at all. You might just as accurately say that early dinosaurs have an essentially Pseudosuchian quality to them. Dinosaurness is something of a perceptual trick.

This happens more often than you’d think. In 1916, English zoologist L. A. Borradaile coined the term “carcinisation” to describe the curious process by which several independent lineages of crustaceans arrive at crab-shape. What, then, is a crab? You might say that a crab is a specific family of crab-shaped animals of the order Brachyura.

In this you would be scientifically correct — but according to this logic, king crabs aren’t true crabs; neither are hermit crabs or porcelain crabs. Cyclid crustaceans looked remarkably like crabs, and pre-dated them. But they weren’t crabs either.

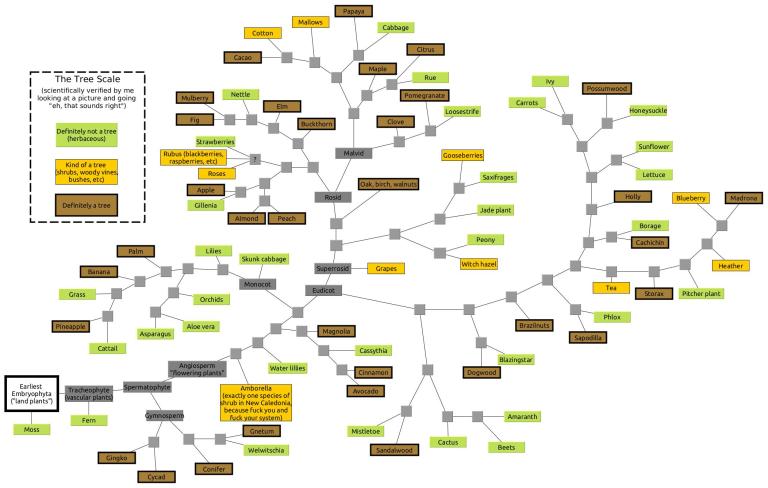

And if you think that’s complicated, then realize that according to our system of scientific filing, “trees” are less a distinct sort of plant than a phenomenon that appears in various lineages at various times. So, for that matter, are “fruits,” and “wood.” These exist, and you know them when you see them. But many of the examples you can call to mind are not from meaningfully related lineages. Magnolias and pine trees aren’t that related; neither are Magnolia and Madrona trees, which look much closer. The last common ancestor of a peach and an apple, meanwhile, may not have been in any way recognizable as a tree.

There is likewise some mammalian eddy that sweeps in unrelated carnivores and makes them look rather like cats, with saber teeth. Thylacosmilus, a South American predator whose saber-teeth were accompanied by strange bony scabbards on its lower jaw, was a marsupial, making it evolutionarily further away from the saber toothed Smilodon than we are. The nimravid not-quite-cats evolved hyper-long canines as well; all of the various mammalian sabertooths also independently evolved hyper-wide gapes and strong, grappling forelimbs, a package of traits sometimes called the “saber toothed suite.”

The point is that as generally used, “dinosaur,” like “tree,” or “sabre-toothed cat,” isn’t reflective of a specific biological lineage so much as, well, a way of life.

The annals of taxonomy—that ever-changing system by which we attempt to bring some sort of filing order to a world that staunchly resists it—are full of such stories: of things that seem to belong to one group but actually belong to another, of lineages that echo and converge on similar body shapes and lifestyles. A snake is a type of lizard, but it isn’t the only snake-like type of lizard, as at least 26 lineages of lizard have independently lost their legs at some point. (We might easily coin the term “ophidization,” the process whereby certain sorts of lizards become essentially snakelike. Except that amphibians do it too, and so do fish: eels and sirens and cecilians all look rather like each other, even if some of them have limbs and some don’t. Do these fall under the label of “ophidization?” If not, why not?)

How do we best categorize this? Convergent evolution—that animal populations separated by vast gulfs of time and genetics can acquire similar shapes—is a well-known scientific concept. But “well-known” is not always the same thing as “well-understood,” and knowing that something happens is not the same thing as knowing quite why it happens. There are benefits, it seems, in certain essential shapes, certain suites of adaptations—if you are of a lineage that can unlock them. The high-stepping archosaurs that gave rise to crocodiles, pterosaurs and dinosaurs unlocked bipedality multiple times; their hollow bones also meant that they could unlock flight, and did, multiple times.

Crucially, these were not directed processes; they were simply things that happened. Given enough time—and millions upon millions of years is a reservoir of time deep enough for anything—most things do.

Crabs exist. Trees exist. Snakes exist. Dinosaurs exist. They exist both as distinct, scientifically understood groups and as functional phenomena, and the two are only tangentially related to each other. We might correctly say that Poposaurus is a specific animal that does not belong to the group Dinosauria and is not particularly related to it. But we might also remember that if we saw it scurrying away through the underbrush, a hatchling clutched in its jaws, it would seem like a distinction without a difference. Dinosauria are a specific sort of animal. Dinosaur-shaped is a phenomenon, and the world probably has not seen the last of it.

More below the jump. Stay with us.

DOGS, CATS, PIGS; MICE, MOOSE, SHEEP

Once you start to slide a wedge in between logical (or biological) taxonomy, and functional taxonomy, it opens up an entire world. Consider the perennial TikTok comedy trend of people presenting the imagined pitch meeting behind such complex, pastiche memetic systems as the analog clock or English’s totally baroque system of animal plurals. (This incredulous reading of animal groupings — “A group of ferrets is a business?!” — deserves an honorary mention.)

In that last one, picture two characters: a hapless functionary, taking the minutes, and looking on in growing frustration and disbelief as the madcap creative lays out his vision for English animal plurals. Let’s listen in on the functionary:

- Okay, so you have your cats, your dogs, your pigs. Got it? So it's mouses, right?

- ...

- Wait, really?

- ...

- And so goose is … No. Really?

- ...

- Really? Wait, “ee” as in sheep?

- ...

- Oh, but at least sheep must be …

- ...

- Fuck off.

And here we have something similar to the dinosaurs, or the trees: a mismatch between English as a logical system and English as a functional system.

We have the words we have, and the forms they take, because those are the ones that billions of people have made shaped into being with daily, often unconscious use. The joke is funny because it imagines how the language might have been designed; but the language is the way it is precisely because no one designed it, and because everyone had to learn it and be inculcated into its use by the system of people already using it, who are themselves shaped by the environment they lived in. Looked at as functional tools, English’s mess of animal plurals make sense in the same way calling a Poposaurus a dinosaur does.

Let’s advance a simple theory of English animal plurals, to cut away all the wrangling over mice and meese. We’ll argue that there is only one main characteristic that determines whether an animal is going to have a standard plural or a weird collective one.

The rule is:

- If it is an animal you interact with personally, or one-on-one, it gets an ‘s.’

- If it is an animal you interact with collectively, it gets a weird Anglo-Saxon collective noun.

To wit: If it's an animal, and particularly a domestic animal, that humans interact with one-on-one, the rule is simple. It gets an s. Dogs, cats, even pigs. You have one, or you have two — and these are quite different. (Second dog is quite different from first dog; third dog will add its own categorical difference)

Then there are animals that we generally don't interact with one-on-one, but that tend to live communally or anonymously. Those it gets a collective noun. You either have one mouse on your floor, or you have mice in the walls. You either have one goose, which you are, for example, preparing for dinner, or you have a bunch of angry geese coming at you on a river bank all hissing and flapping.

And there are special cases, like collective nouns: you may pluralize “crows” using the personal model (which makes sense for such a personable bird) but at some point there will simply be a “flock.”

The unitary word “flock” conveys that there are also the animals where number is basically irrelevant. In the case of “sheep,” that's because the unitary sheep is not a meaningful category. People may keep a couple of nanny goats, but nobody just has a couple sheep. (But what happens once you start to sort it? Why, there’s the ‘s’ again. Rams, lambs, and ewes.)

An extreme example of the principle is seen with “moose.” We’ll argue we don’t use an ‘s’ because the moose is a herd animal, largely encountered in groups. But why wasn’t a separate, special plural invented?

Perhaps because it wasn’t necessary. As anyone who has been close to a moose knows, any amount of moose is an unmanageable amount of moose. One moose is too much moose. As is two moose. Or three moose. The numbers offer an adjectival color and archival precision but no meaningful clarification. To a small pink creature like us, there are only two operative states of moose: yes and no. Moose is, or is not.

NO SUCH THING AS AN ANIMAL

Of course that goes to show that there is some order there, but it doesn't explain why the actual pluralization -- between mouse and goose and mice and geese -- is so different. One answer is because, in many Indo-European languages, vowels get pluralized by a change in the word itself rather than adding a suffix, and different vowels have different, but still formalized, transformations.

These collective nouns, in English as in—say, Russian—follow no discernible pattern, which makes them hard to memorize. But that makes sense if you consider them as optimized not for ease of memorization — a Latvian immigrant could probably live a long and satisfying life saying “sheeps” — but rather as functional groupings: a workaday toolkit of what was once a daily household economy. From this perspective, the “animal” words turn out to describe a set of creatures and accompanying chores so different as to defy the idea of a shared pattern.

The habitats and the work required — the habits and folkways — that go into the upkeep of sheep versus pigs, goats versus cattle, are so radically different that it might have seemed strange, to a rural English speaker even a century ago, to think that they would need to follow any consistent naming convention.

In fact, let's flip it and ask: why expect that there would be consistency in a group like “animal plurals?” We’d argue it betrays how far we have come from living with other creatures: in families like ours, we now at least three generations, many of us, off the land and out of any sort of working or functional relationship with "animals." In fact, animals” is a category that is itself so broad as to be utterly useless. (Unless you live, say, as we do, in a small urban lodgings where the animals we interact with are either lizards or cats — or whatever exotic animals we see online.With which, to be fair, we may feel a very personal relationship.)

Which is why, in the Austin enclave and the the Washington Soviet, we have declared a new rationality to English pluralization: One bear, two bears; one pangolin, two pangolin; one sheep, two sheeps.

CATEGORIES CAN KILL

So why are we talking about this, anyway? Because categories, like any tools, are as much governed by evolution as the world they describe. Specifically, they are built and evolved based on the functions they serve. That doesn't mean that everything they do is functional. As in the biosphere, things can camp out for a very long time in a linguistic niche that serves no clear purpose at all, provided there is not some force to erode them down.

What does such a force look like? Well — when people question the categories, or stop using them, the language gets worn down a little bit more until a more simplified form. Essays like this one bring the world of “sheeps” a little closer.

Words and concepts may be conserved for a long time, until suddenly their niche disappears. Big picture, this is why, for example, English stopped distinguishing between “thou” and “you:” when a somewhat more egalitarian society emerged, and the idea of a matrix of social propriety and hierarchy oriented toward one’s betters eroded, “thou” fell out of use, to survive only in fossilized form: e.g. Shakespeare’s sonnets. (An interesting wrinkle of this is that “thou” was actually the familiar form of you — equivalent to Spanish or French “tu” — and that “you”, the formal version, came to cover everyone in a new blanket of respect.)

Thus key question with linguistic and category systems, as we will be exploring in Heat Death, is not whether they are true but whether they are useful to the new situations in which we find ourselves. As Scott Alexander writes in one of the permanent internet essays on this topic, the categories were made for man, not man for the categories.

Which is to say: A lot of inadvertent evil gets done by people trying to make the world fit the categorization system built on a prior or incorrect or obsolete understanding.

Bonus question. Saul came across this classic article from Science arguing that humanity was, and should be treated as, a unique “superpredator.” Here the definition offered is of a kind of predator that is able to prey on the oldest, largest, and presumably fittest of its prey species — rather than following the usual predation strategy of targeting and picking off the old, sick, and young.

Here, “superpredator” is used as an analogy, and also as a kind of revelation, and attempt to pull back the veil and show us a relationship in a different register — and to suggest that we should treat humans as we would any other problematic species in a given ecosystem, with “additional constraints by managers.”

The question is, do you find that useful or convincing? Write us and let us know.

WHAT WE’RE UP TO

Asher here. I’m in the process of putting together a story for Texas Monthly about the Conservation Centers for Species Survival, a sort of broker/middleman for various organizations that work with exotic wildlife breeding, from zoos to ranches. The story mostly focuses on the Red Wolf, an extremely handsome and critically endangered canid that’s the only mammalian big carnivore native to the United States. To that end, I headed out to Fossil Rim Wildlife Center, a converted exotics ranch that now hosts breeding programs for several species of animal, including Red Wolves.

However, I’m not here to tell you about them. I’m here to tell you that I got to meet several cheetahs (carefully, from behind chain-link fences) as the carnivore curator brought them their meals. The three cheetahs seen here were hand raised by the curator after their mother had some medical issues: you can hear them purring like motorcycle engines when they see him. The other cheetahs were not nearly so friendly: there was quite a lot of hissing and flattened ears and a few swipes at the chain-link. This is good, as it happens: Fossil Rim is interested in keeping the wild animals as wild as possible, and wild means viewing humans with considerable and justified suspicion.

Anyway, for your edification: a sneak peak behind the scenes of the Fossil Rim cheetah program, containing three rambunctious adolescents.

Plus, a female who wasn’t on the feeding schedule, and so registered the time-honored feline complaint. Heartbreaking: area cheetah has never been fed in entire life, reports area cheetah.

Saul here. I had a couple pieces out this week. First, this one, about the question of how dryland cities from Baghdad to Phoenix survive in a world where water is going to be at a premium.

Second, in a wildly different mode, I have this interview with business mogul Jack Stack, who helped turn a failing engine factory into a thriving co-op by, in part, learning to roll with recessions.

Until next week, this is Heat Death.

Member discussion