When The Desert Blooms

Asher here. October is generally meant to be Austin's wettest month, the time when the reservoirs and aquifers refill and the forests shrug off the grip of summer. Nobody seems to have told the weather. It's been weeks since it last rained noticeably in Central Texas. After an unusually wet span of weeks in the summer – one that saw widespread catastrophic flooding in parts of the Hill Country – the drought has crept back in, closing bony fingers around the landscape's throat. The garden wilts. The plants droop. The grass dies, and the lawns are choked by dust.

With no storms in sight, and no clear sense of when any might arrive, it's hard not to look up at the sky and wonder what's gone wrong. Harder still not to wonder what it might take to make things a bit more... predictable.

Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that spends too much time praying for good weather. That's a common sentiment these days, and one that echoes far, far back through time.

Every human society has depended, to one degree or another, on the regular, dependable availability of water. Water to drink, water for the crops, water to feed the pasturage. You could argue that the entire story of human communal civilization has been the struggle to ensure that water will be available. Sometimes that's ancient technologies: the irrigation systems that divert currents from rivers to feed vast fields, or wells bored deep into the water table. Sometimes, it's more occult and ritual practices: reaching out to the vaster forces of the universe, the spirits and gods of the upper air, in hopes that they'll send a bounty of black clouds.

But starting at the end of the 19th century, freelancer Israel Kolawole writes, something shifted: people began to claim that they could produce rain on demand. And it only got weirder from there.

It's Heat Death. Stay with us.

Heat Death is an entirely reader-supported newsletter, and all proceeds go toward paying guest writers and maintaining our web-hosting.

If you enjoy what we do here, please leave us a tip or sign up: paid subscriptions start at just $2-$5 a month.

The Forgotten Science of Rainmaking

Israel here. The desert has a way of making promises it won't always keep. After the early spring rains, the months of stillness break, and the bare soil flashes with improbable color: golden poppies, violet lupine. A green sheen where the wind had once lifted only dust. For a few days, it feels as though some hidden pact between earth and sky has been honored. Standing on the edge of the Mojave in March, the air thin and cool, I remember poppies rippling in the breeze, a field of gold so bright it almost seemed to make a sound, like sunlight breaking into brass.

The transformation is enough to make you wonder — half-seriously, half out of wishful superstition — if it could be summoned on command. That human will, or cleverness, might coax water from a stubborn sky.

That temptation has been with us for a long time. Across the American Southwest, the Hopi Snake Dance was traditionally part of a yearly rhythm, tying prayers for rain to a relationship with land and community. (The ritual is still practiced today, though many Hopi communities observe the full rites only in alternate years, and the sacred rites are closed to tourists.) Historical accounts depict dancers holding live snakes — messengers to the underworld — and moving in deliberate patterns meant to mirror the clouds’ gathering.

Nor were they alone in doing so. In parts of West Africa, Tiv and Yorùbá rainmaking traditions wove songs, offerings, and precise seasonal timing into their cycles, the chants calling out for balance, inviting the spirits of thunder and river to join in reciprocity. And in Aboriginal Australia, the Da:wajil ceremony has long been performed to encourage clouds to build and release rain over the desert. Dancers painted with ochre sang ancestral stories of creation, tracing the paths of water spirits across the sky.

Outsiders, armed with barometers and skepticism, have often reduced these practices to the question of whether they “work,” missing the point entirely. The above rituals were communions, invocations of cosmic balance, agreements to keep the world in motion. They did not see the production of rain as a "project" but as a conversation — a kind we’ve mostly forgotten how to have. To speak with the weather required patience, humility, and attention to rhythms beyond any human control.

Not everyone has tried to court the clouds, of course. Some have tried to command them. Toward the end of the 19th century, some Americans and Europeans had concluded that explosions helped provoke storms. In the hopeful 1871 treatise War and The Weather, one author argued that the cannons fired in Civil War battles had caused rain. The Department of Agriculture tried to test it by sending the flamboyant, fast-talking Robert St. George Dyrenforth and a team of artillerists to Texas in 1891, where they used to dynamite, mortars, exploding balloons and other weapons to wage a literal war on drought. (The team took credit for any and all rain that followed, despite the early departure of their meteorologist and their lack of a rain gauge.)

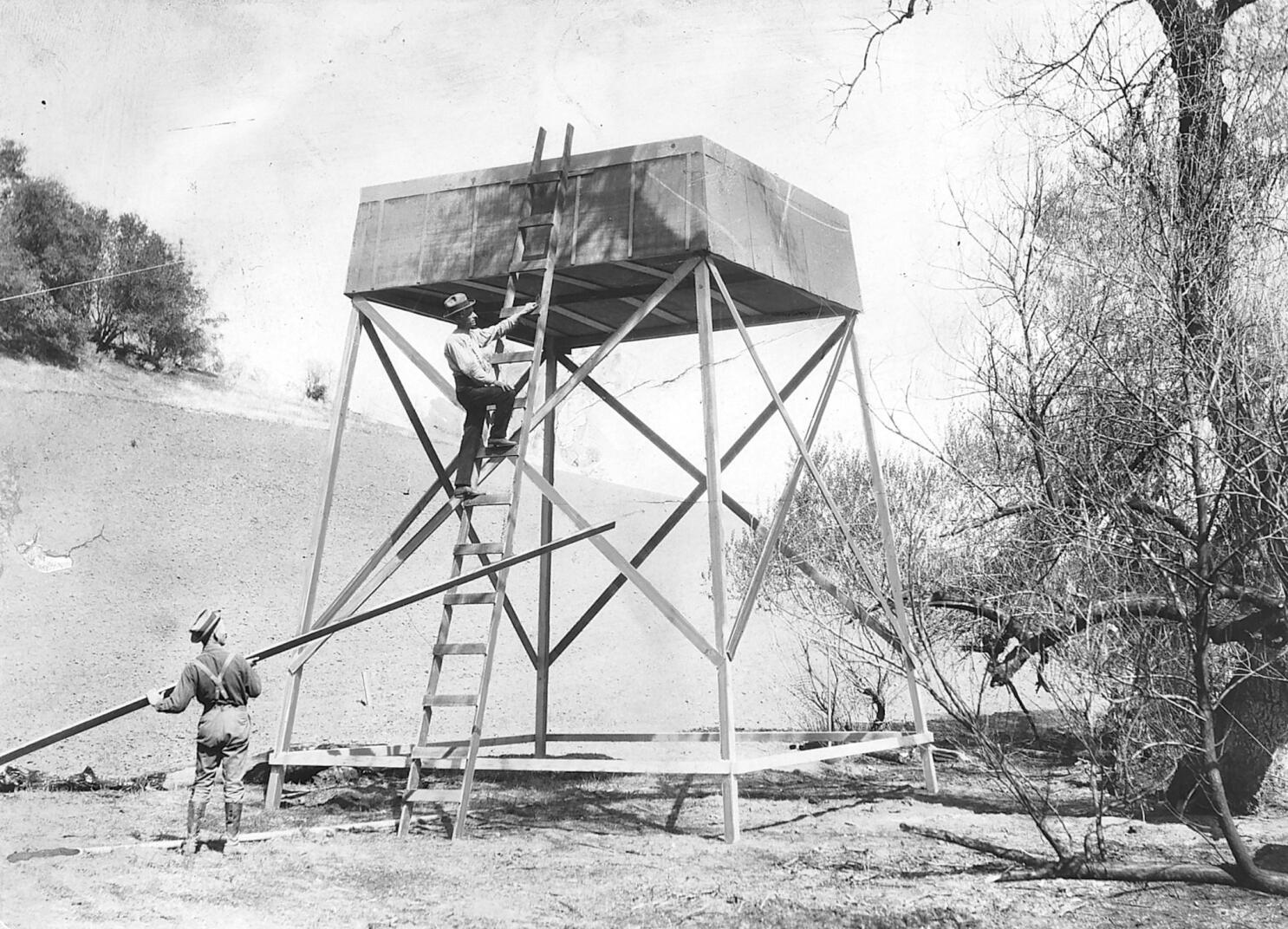

Others thought noxious fumes might be the answer, leading to a parade of "rainmakers" seeking contracts in the midwest and California. One of them was the self-styled “moisture accelerator" Charles Hatfield. Amid a drought in 1915, he promised he could fill the San Diego's Morena Reservoir for $10,000.

Hatfield built a wooden tower by the water’s edge, mixed a secret blend of chemicals in metal pans, and waited. The clouds came, and then the rain — days of it —unspooling into floods that tore out bridges, drowned fields, and killed at least a dozen people.

Hatfield insisted he’d kept his word; the city argued that if he had, he owed them for the damage. No one could prove whether his concoction was the cause, but that didn’t matter. After months of wrangling, the city refused to pay, and Hatfield quietly slipped out of town — neither sued nor compensated. He went on to chase contracts across the West, promising rain to drought-stricken farmers and county fairs alike. His legend grew. His success remained unprovable.

It's hard to know what's stranger: that a major American city trusted a man with a bucket of chemicals to bring the rain, or that nature seemingly delivered. Maybe the times invited belief: industry was conquering distance, electricity was mastering light, and science – or something that looked like it – seemed capable of anything.

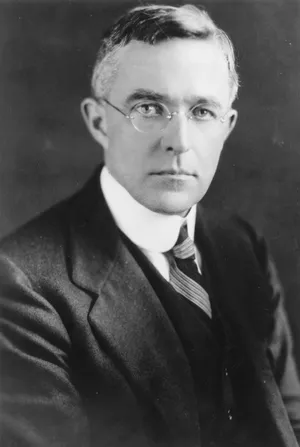

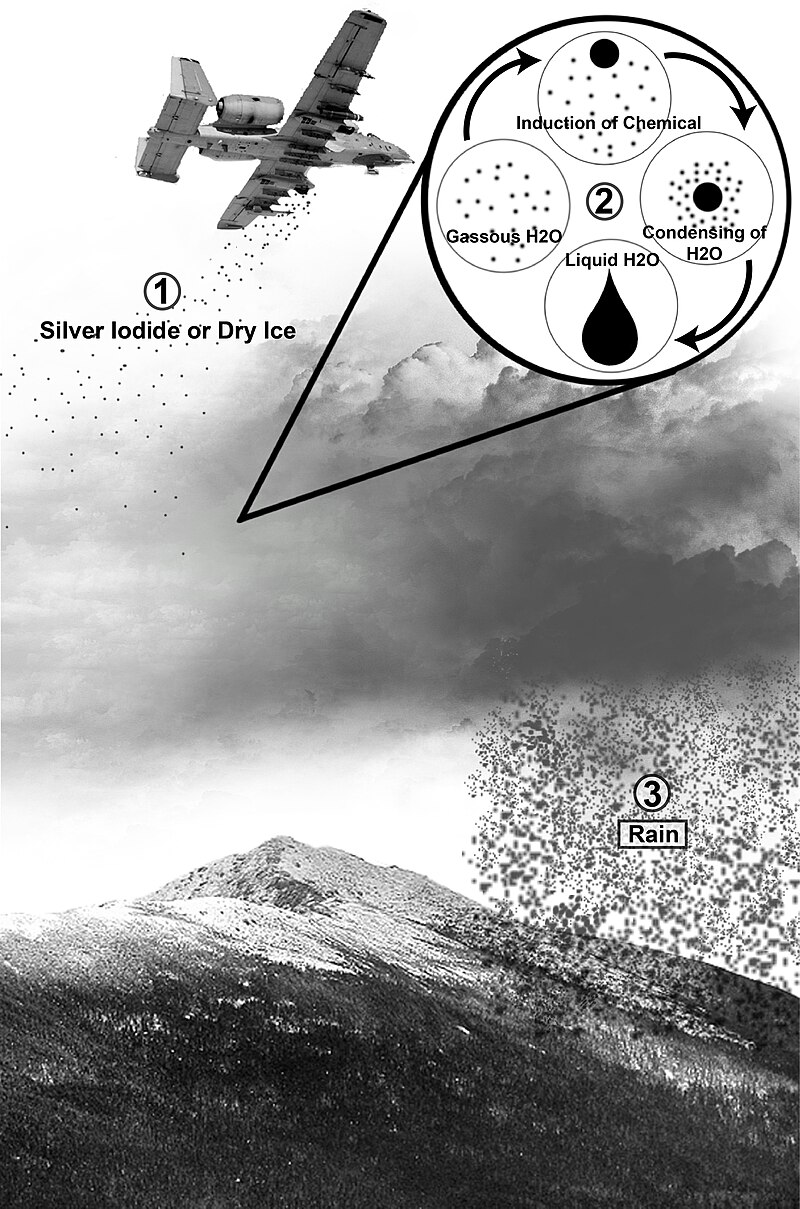

By 1946, Americans were fully intoxicated by the belief that science could not only predict but command natural forces. No ethic of patience or reciprocity could survive the postwar rush to master the elements. Inside the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York, Vincent Schaefer discovered that dropping dry ice into a box of supercooled vapor could instantly produce snow. His mentor, Nobel laureate Irving Langmuir, saw the potential immediately, and soon they were testing the technique in the sky over Massachusetts’ Mt. Greylock. The researchers worked in freezer rooms lined with black velvet so the snowflakes showed up against the dark, each one spinning into existence like a conjurer’s coin trick. One of their colleagues, Bernard Vonnegut (older brother of Kurt Vonnegut) soon found that silver iodide could work even better, its crystalline structure closely matching that of ice.

These early successes sparked Project Cirrus, a joint GE–U.S. military effort that famously seeded — or claimed to have seeded — a hurricane off Florida in 1947. Shortly afterward, the storm changed course toward Savannah, Georgia, tearing through the coast with heavy rain and gale-force winds that flooded homes and toppled trees from Georgia to the Carolinas. Lawsuits loomed. Langmuir declared he was “99% sure” the seeding had caused the shift; later analysis cast doubt on that, suggesting the turn may have been coincidental.

It turns out that convincing the public that you control hurricanes is much easier than proving it. Hatfield had learned that lesson decades earlier, when his “successful” rainmaking possibly drowned a city, and certainly left him unpaid. Both men were caught in the same paradox — that the line between mastery and accident is as thin, and as shifting, as a weather front itself.

It’s one thing to wish for rain on your own fields, of course. But by the late 1960s, weather control picked up a darker edge. As the Cold War progressed, weather modification joined the same vault of "mad science" projects as MK-Ultra’s mind control experiments and the Pentagon’s psychic warfare research — attempts to harness previously unharnessable forces for military supremacy. A nation that believed it could potentially command the weather was also one that could contemplate flooding someone else’s roads for strategic gain.

And so in Vietnam, the U.S. military launched Operation Popeye, a classified cloud-seeding campaign designed to extend the monsoon season over the Ho Chi Minh Trail and bog down enemy supply routes. "Recently improved cloud seeding techniques would be applied on a sustained basis," a 1967 classified memo dryly remarked, "in a non-publicized effort to induce continued rainfall through the months of the normal dry season." Between 1967 and 1972, aircraft released tons of silver iodide into tropical storm systems, an aerial ritual meant to weaponize rain itself.

Whether it worked remains murky. Pilots claimed success, reporting lengthened rainfall and softened terrain; later studies found no clear proof. As with Hatfield and Langmuir before them, the line between cause and coincidence blurred. When the operation was exposed by investigative reporters in 1971, public outcry erupted in the United States, sparking debates in Congress and condemnation abroad. Vietnam itself, already ravaged by chemical warfare, bore silent witness to this new frontier of environmental manipulation. By 1977, the backlash culminated in the ENMOD Treaty, signed by dozens of nations, which formally banned environmental modification for hostile purposes.

But these grand visions — whether pro-social or sinister — were winding down by the 1980s, eroded by too many rounds of inconclusive results. Instead, utilities and water districts in mountainous areas of the United States began funding “orographic” cloud seeding: launching silver iodide into clouds already moving over cold mountain peaks, hoping to squeeze a little more snow from the sky. Sacramento Municipal Utility District has used cloud seeding since 1969 over the Upper American River Basin to increase mountain snowpack, working on the theory that melting snow should increase hydroelectric capacity. The Utah Division of Water Resources runs a similar program, for similar reasons.

The pitch here is modest: don’t conjure storms, just make the most of the ones nature sends. But proving even these limited effects has been maddeningly difficult. After all, you can’t replay the same winter twice — once seeded, once not— and compare.

The best evidence has emerged only in the last few years. In 2020, scientists working on the SNOWIE project in Idaho captured a rare and unambiguous radar signature of seeded snowfall forming exactly where and when it should have, downwind from silver-iodide plumes. It was the equivalent of catching the act in slow motion: seeded clouds producing extra snow in a clearly defined ribbon across the landscape. Yet in Israel, a decades-long cloud-seeding program ended in 2021 after a carefully designed randomized trial found no statistically significant increase in rainfall. The contrast feels almost like a weather forecast itself — clear skies here, storm warning there — proof that the atmosphere answers only to its own conditions.

Nonetheless, Lower Basin utilities are funding seeding efforts in the Upper Basin, with help from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which has contributed millions to boost snowpack in key watersheds. Silver-iodide generators now stand like quiet sentinels on ridge lines; small planes wait on standby for the right cloud structures to appear. Supporters call it a low-cost, low-risk supplement to water management. Critics point out that even if the physics checks out, the politics are murkier: if one region “makes” more precipitation, who decides where it should fall? As one Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists piece warned, cloud seeding’s promise of control could easily become a “silver bullet” aimed at the wrong target.

It’s here, in this mix of science, hope, and politics, that the parallels to today’s geoengineering debates become unavoidable. Where cloud seeding aims to adjust precipitation, solar geoengineering proposals aim to adjust global temperatures —brightening clouds over oceans or releasing reflective aerosols into the stratosphere. The scale is larger, the stakes higher, but the fault lines are familiar. In 2023, the White House released a plan to evaluate research into solar radiation modification, careful to stress that studying the idea was not the same as endorsing its use. That same year, Mexico banned solar-geo experiments outright, reacting to unauthorized tests and concerns over governance. And in 2024, Harvard’s planned SCoPEx experiment — set to test equipment in the stratosphere — was canceled after years of resistance from Indigenous Sámi groups, environmental advocates, and scientists who argued that the governance framework wasn’t ready. Swap clouds for climate, silver iodide for sulfate particles, and you can feel history clearing its throat to tell the same story again.

Rainmaking’s record is a ledger of unintended consequences and contested credit. Hatfield’s floods, Cirrus’s hurricane, Popeye’s monsoon extension — each revealed how easily a technological promise can blur into a political crisis once nature refuses to cooperate. Even the most rigorous modern assessments, like the U.S. Government Accountability Office’s 2024 report, acknowledge that while seeding can produce measurable effects under certain conditions, translating those results into reliable, equitable policy is another matter entirely.

Weather modification no longer seems like something that should be abandoned or embraced wholesale: it calls out rigorous measurement, transparent decision-making, and the willingness to stop when the risks outweigh the rewards. To engage with it means recognizing that the atmosphere is the definition of a shared space — one we alter at our peril, and at one another’s expense.

Some shadowed understanding of that fact stalks the darker corners of the internet. In the wake of catastrophic floods in North Carolina and Texas, social media buzzed with claims that cloud-seeding operations or “weather weapons” were to blame — proof, believers said, that governments can steer storms at will. Like many conspiracies, it arises out of a misaimed analysis of something real. The irony is that we have changed the climate: our CO2 emissions have thickened the air, warmed the seas and skies, and twisted storm systems into new patterns, contributing to the very droughts we're now fumbling to solve. Who needs a pulp-science superweapon? The Colorado River is at historic lows, and the reservoirs it feeds — Lake Mead, Lake Powell — are shrinking. An age of mega-droughts seems to be speeding in over much of the American west; when the rains come, they come either too little or — in mockery of Hatfield – too hard. We’ve always wanted to command the clouds; instead, we’ve accidentally managed to rewrite the sky. There's something mythic about the way the predictable, beneficial intervention we seek hovers just out of reach, while the damaging side grows and grows.

And yet the dream persists. It does so for reasons of basic practicality: in a warming world, even a few extra inches of snow can mean fuller reservoirs and fewer restrictions in summer. But part of it is older and harder to name. It’s the same impulse that drove the Hopi to their dance, Hatfield to his tower, and Schaefer to his dry ice — an unwillingness to leave something as essential as water entirely to chance.

One winter morning in the Great Basin, a generator sends a stream of silver iodide into a passing cloud. Hours later, instruments detect a narrow band of extra snow. It’s not much — no one will write a ballad about it — but it’s real. In a few months, the desert might bloom again, setting forth its golden fields of poppies, renewing ancient promises.

When it does, maybe the truest thing we can say is neither “we made this” nor “we had nothing to do with it,” but something in between. We nudged. We hoped. And we remembered that the sky always has the last word.

Israel Temmie Kolawole is a freelance writer whose work examines how human imagination shapes our relationship with the natural world.

This has been Heat Death. We're entirely reader-supported independent media. If you like what we do here, feel free to subscribe: paid memberships are just $2 t0 $5 a month. (Or you can always leave us a tip.)

While we're growing, the single most helpful thing you can do is send it to someone you think will like it or post it on your favorite social with a nice note. We are, above all, a word-of-mouth operation.

We'll be back soon with more musings on past, future, and all the crises in between. Until next time, just remember that fundamental desire of humanity:

Member discussion