World's Finest, Forever and Ever

There’s an old parable they tell in the British Isles and the American Northeast about a traveler, lost in some gravel-trailed hamlet, who asks a local farmer for the best way to a nearby town.

“Oh,” the farmer says, plucking at the straps on his overalls, “If I was you, I wouldn’t start from here.”

Aside from the universal humor in hearing someone get told, politely, “Buddy, yer fucked,” the joke illustrates a key principle of evolution that helps set up today’s guest essay about the very different paths taken by Batman and Superman: the principle of path-dependence.

Path-dependence means that where things start from matters. Initial conditions—be they biological, technical, or cultural—begin to shape and constrain both the kit you have to work with, and the options you have to use it. The contours of the route constrain your choices and shape your options, guiding you down the path of least resistance — a steep-walled canyon that funnels everything (organisms, new technologies, and Kryptonian god-men or tortured New York vigilante billionaires) down through a much more restricted set of options than might seem to initially present themselves.

To try and escape the path upon which one has become dependent is to take the perilous climb up those walls. One false step is all it takes to send you plunging back down to the role that fate and circumstance had assigned.

Welcome to Heat Death, where free will and determinism scour the streets like caped crusaders, working together to keep all and sundry in their assigned places — and where, every now and then, things manage to break loose.

It’s been a quiet and contemplative couple of weeks for the Brothers Elbein, both of whom are in Austin at the moment. We were off last week for the Jewish High Holidays, a period of facing the choices you’ve made and the impacts those had on you and the world around you. That’s been tough in the age of coronavirus: there’s nothing stranger, in a faith so inescapably communal, then having to celebrate it solo. (What’s even the point of fasting if you can’t turn to the person next to you, who is also fasting, and complain?)

So it’s good to be back with you, and particularly since we have something special today: a sharp essay from guest writer David Mann, which looks at the strikingly different pathways taken by two demigods of the modern American cultural canon: Superman and Batman.

It’s the kind of multi-layered piece we love to run at Heat Death: a nicely-narrated cultural history of America through an accessible romp through one of its niche cultures, which turned out to be the rare bit of comics writing that held Saul’s interest all the way to the end. But it also returns to some of the deeper themes that interest us here: about how things become other things, and about the hidden tapestry of a world that seems, from that pristine map view, so simple. (They also take on some of the questions Saul asked in his essay on the life and death of cultural forms, “Some Things We Must Led Die.”

All of which is to say: if you have such a story kicking around — like Annika Tara’s recent, wildly popular piece “Your Skeleton is Nonbinary Too” — we’d love to hear about it. We are still only able to pay a pittance — we like to think we put the “honor” in honorarium — but you’ll end up with what Annika and David did: a clean, well-edited draft that helps you sharpen, focus, and share your ideas.

It's Heat Death. Prepare to become fictional.

World's Finest, Forever and Ever

David here. When Heat Death was launched and I mentioned this would be the first ever newsletter I’d be subscribing to — a decision I haven’t regretted — Asher Elbein kindly let me know I’d be welcome to do a guest essay when that became something the series was in the business of. I appreciated the offer tremendously but figured I’d keep it in the back pocket. I wanted to be sure my brand of comics discussion would match the ethos and interests of Heat Death, and also be reasonably accessible to folks who had mainly come here for extended reflections on, say, the limitations of taxonomy, or the subtle architecture of the perfect toast, at least as much as ruminations on pop culture.

But the piece wouldn't let me go, and they've given me the space and editing to help this idea grow into a piece all its own. Given that the result is a narrative of iconography, adaptation, and the unspoken, unconscious reasons why certain shared stories are told the way they are, I believe this makes Heat Death a fine home for it.

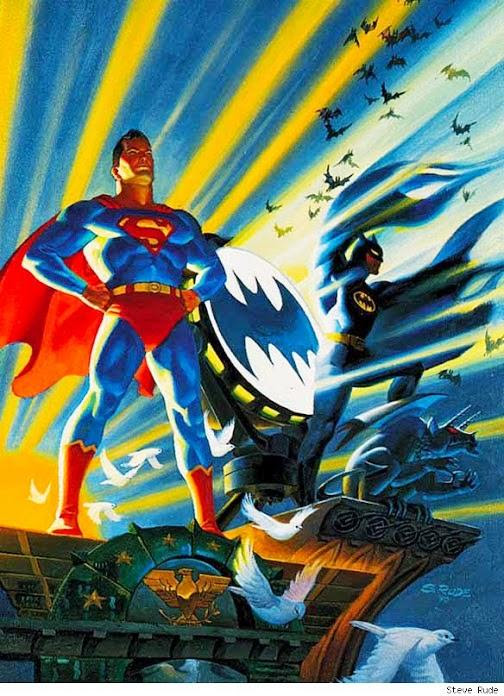

So here is something odd to reflect on: when Superman and Batman made their comics debut in the 1930s, they were shockingly close to being the same character.

Forget the trappings, and consider the barest narrative mechanics. First, the innocent son of an Arcadian world finds that world explosively stripped away. He hides by day in a hapless constructed identity, using the uncanny privileges that are his final inheritance to prevent the same tragedies from being inflicted on the people of his new, chosen home. If one flies while the other uses a grappling hook, that matters surprisingly little: practically speaking, it usually amounts to little more than how they’ll arrive to knock out the no-goodnik of the month. (One flies, the other takes a car. But they both get there.)

No doubt many of those similarities are owed to Batman being the first viable attempt to recapture the Superman template (or less charitably produce a successful knockoff) on the heels of the latter’s early success. But even after the better part of a century, with every change that eventual gestalt idea of the ‘superhero’ has undergone - shaped by and shaping their own progression - their roots remain uncommonly close among their kind.

Or to put it bluntly: Batman is wearing a spooky version of Superman’s costume, and once you notice that, you’ll never not notice it again.

Are there more substantive differences that do manifest between them? Certainly. But on an adventure-by-adventure basis most of those differences have emerged from the scaffolding of ‘mythology’ and continuity emerging across 80 years, or from how those ideas became refracted through the prisms of their respective subgenres of adventure fiction (whose roots we see in their original books’ titles of Action and Detective). Over time, that has also given the two stories a stark tonal difference that helps cover up their underlying similarity. In Superman’s aspirational sci-fi world, family and community can be found anew in the wake of disaster; identity embraced and nobly lionized; the day brightened by lives saved and love found. Meanwhile, the only enduring gifts of Batman’s past are cold cash, a suffocatingly empty manor, and a bottomless well of pain to channel. The emotional ties he reclaims can still never escape the gravity of endless, shadowy alleys and the monsters and mysteries they hold.

But while that’s an effective — if a bit reductive — summary of the ‘steady state’ of their core ideas, a more complicated difference appears when the two are observed across a broader historical scale. Let’s push past the old saw about Batman being a figure of the dark, while Superman's all about the light: More turbulent eddies await. Maybe the most foundational difference between the two lies not in any individual change from the core idea, but the ways in which corporate dictate and fan response allow them to change.

To do that, take a good look at the photo above. What differences do you notice?

Both Superman and Batman received special covers for their respective 80th anniversaries, tracking their changing iconography over the course of their publication history. These, as drawn by Nicola Scott, are instructive. Let's take them one at a time.

Aside from a little fiddling with the S-Shield early on and the divergence of the 2011-2016 ‘Kryptonian armor’ uniform, all of the Supermen look almost exactly the same. Scott has to play heavily into different colors, logo sizes, and facial structures reminiscent of assorted artists across the decades to visually differentiate them. But each of them is giving an entirely different expression: neutral, bemused, beaming, stern, vaguely smug. What differentiates Supermen from each other, in other words, are their faces.

As a group, meanwhile, Batmen come in vastly different shapes, sizes, and aesthetics, even while building off a shared template. Yet all confront the reader with a look of solemn determination; only the center Batman of the top row breaks from the pack enough to muster a full-throated smile, and with the narrowing of his eyes it comes off as nothing so much as a hunter’s triumphant sneer.

Whatever the degree of her conscious intent (likely considerable, given she’s very good at what she does), Scott captured a fundamental line of demarcation here: Superman is permitted internal change, Batman external.

But let’s backtrack a moment, and talk about creation myths. The story is well-known enough to be rote among those who closely follow the character: Superman was created by two Jewish kids in the Great Depression, as a figure with only the (relatively modest) ‘strength of ten men.’ His crime-fighting targeted the likes of businessmen mistreating their workers and war-mongering politicians more than gangsters or alien tyrants.

But when World War II reached the nation’s shores, the idea of America’s caped wonder dragging corrupt senators through the sky wouldn’t, ah, fly. And so the almighty, guileless super-patriot we recognize today from greeting cards and cereal boxes was born.

But by the time that profound shift in character occurred, Superman had already become an icon. He’d made the leap from comics to radio and — a scant few months prior to Pearl Harbor! — the big screen, in the iconic Fleischer Studios cartoons (which notably already had him fighting mad scientists and monsters rather than the comics’ politically-charged foes). He was on all manner of merchandise and made an appearance at the 1939 World’s Fair.

Moreover, the most important conceptual and visual touchstones of Superman’s narrative were almost all there from day one. In 1938’s Action Comics #1 we got the death of Krypton, the alien child’s discovery by the Kents, the suit (give or take a few quick-in-coming tweaks), crusading Lois and his adoption of the alter ego of shy bespectacled Clark Kent at the paper. We got his feats of strength. And while he couldn't technically fly yet, you wouldn't know it to look at Joe Shuster's pencil work.

Within 5 years of his creation, in other words, it was understood that there were certain ways a Superman story should look and play. His catchphrases, voice actors, logos, and the exact phrasing of his powers and origins were soon being coordinated and stylized across mass-media. The result was a durable popular impression, one that lingered long after movies and TV began to branch out somewhat with their depictions of the character.

Some stories attempted to move beyond this template. Sometimes the results are fascinating, and even ahead of their time. In Grant Morrison and Rags Morales’ 2011 Action Comics, a reboot puts a brash young Superman in work-boots and a T-shirt. Rather than Lex Luther or the usual suspects, Morrison and Morales pitted him afainst a fifth-dimensional magician who's both the embodiment of institutional power and the Devil. (Superman also squares off with an evil Kryptonian who’s simultaneously a mummy, a sorcerer and a ghost. It rules.)

Others are … very much of a moment in time, like this moment from 1993’s Adventures of Superman #504, in which writer Karl Kesel and artist Tom Grummett depict Superman (who recently died and got better, as comics characters are wont to do) bursting his way into his evil replacement’s robo-fortress, guns and pouches akimbo. It was the 90s, you know? Guns and pouches were the done thing.

None of the attempted variations in the iconography — black suit, electric blue suit, no underwear, t-shirt and jeans — ever stuck. But there's a paradox at the heart of Superman, and it’s this: after his 1940s personality overhaul proved popular, his actions and motivations became malleable in a way his public persona — his build, his costume, his catchphrases — were not.

Supeman, in other words, could be a radical champion against our collective accepted indignities, or a suburban godling, privately wracked with neurotic insecurity. He could be a cosmic orphan forever questioning his place in a world not truly his own; a secularized caped Christ; Reagan’s right-hand man (willing or reluctant); an earnest, straightforward farmboy made good in the big city; a tormented avatar of his own significance wrestling with whether his moral authority will continue to endure.

Or he could be any combination of the above, or something wildly different besides. Clark Kent himself could be played as a wistful facade for the shining hero he truly is — the mask of Superman — or Superman could scan as the palatable primary-colored public face that conceals Kent, the sensitive midwestern soul within. As long as Superman stories (1) look ‘right’, (2) make people feel comforted and assured of his unquestionable righteousness the way they supposedly should, and (3) tap the currents of the modern American consciousness in a fashion deemed acceptable, each generation is largely free to depict the character — and his inescapable relationship with the notions of nobility and alienation — as they see fit.

Notably, even as I write this, DC finally seems to be trying out a new approach toward diversifying Superman's public image. Current comics have divided the iconography of the suit between a visibly aged Clark and his son, Jonathan Kent, as the latter becomes Superman himself.

TV will soon be simultaneously presenting him in his early days in My Adventures With Superman and as a 40-something father of two in Superman & Lois. There are also larger overhauls of the concept cooking, like Ta-Nehisi Coates’ untitled Superman film reportedly starring a Black Clark Kent, and Michael B. Jordan’s miniseries for HBO Max putting another Kryptonian in the cape. It’s an unusual move for the company, which generally has preferred not to signpost different takes on the character. But since it’s been decades since a mass-media Superman project found widespread acceptance, it’s probably a necessary one.

After all, embracing that kind of change has certainly worked elsewhere.

Batman — somewhat appropriately, considering his air of mystery — was far less well-defined initially. In his six-page first appearance in 1939’s Detective Comics #27, he has no origin. (It notoriously would not be depicted outside the comics until 1985, in an episode of Super Friends.) His suit seems like a mutated variant of anything we’d now recognize: it has oddly pointed ears, bulging belt, miniscule logo, and mundane-looking purple gloves. Neither Robin or Alfred appear. There are no garish villains, no batarangs or grappling hooks. He drives a regular car.

He’s not a total stranger; with the exception of a cavalier attitude towards the deaths of his enemies, he notably behaves as we’d now expect a Batman to. He emerges from the shadows, unleashes martial arts mastery on doomed goons, unravels a mystery, even escapes a death trap. But what we’d now consider the most elemental touchstones of his world took years to establish. By the time everything had settled into place, he’d undergone a massive stylistic shift. Gone were the minimalist, lightly surreal horror-scented yarns; now he starred in swashbuckling crusades against crime, complete with a sidekick for the kids.

In the early going, The Caped Crusader was, at best, DC’s #2. But paradoxically, that freed up the character tremendously, allowing creators to experiment with far more sizable outward and tonal changes than his rival. For his first 50 years, without the need to embody the pulse of the American consciousness — or having to be the platonic ideal of his own genre — Batman was able to develop in a sort of relative peace. Over the decades, his stories jaunted through sci-fi and pop-camp and noir, riding peaks and troughs of popularity before exploding in the 1980s. (The dual hits of The Dark Knight Returns and Tim Burton’s blockbuster kicked off a Bat-Mania that eclipsed Superman in ways the latter has never quite recovered from.)

But even as the style of Batman story changed dramatically, his personal world gradually expanded with minimal revision— and his quickly-established nature as a caring, clever, steadfast avenger required little tweaking to function through assorted shifts. Recurring themes emerged across decades: Batman’s reckoning with his trauma, his simultaneous longing for a renewed family and fear of loss, a tendency toward reflecting on his mortal limitations, and meditations on the personal costs of the war on crime. With these notions refined in a creative renaissance the 70s and 80s, by the time Batman achieved his own totemic cultural significance he was well-positioned as a character to carry that success forward. He had a thin but visible thread of personality stretching back from his earliest days.

At this point, whether fighting gangsters, B-movie aliens, serial killers, or the apocalypse, Batman is Batman is Batman. For all their outward differences — a courtly tone versus a rasping growl, tactical suits versus spandex, the precise level of murderousness displayed by their giggling foes — Adam West and Christian Bale are playing the same character, doing the same things for the same reasons in the same ways.

It’s easy to see how this contributed to Batman’s eventual popular dominance over his progenitor. Superman as a figure is both beholden to tradition yet constantly in flux: every new iteration has to implicitly deal with the conceptual burden of his entire history. Batman meanwhile can just do new variations on Batman stuff, because we’ve all pretty much agreed we like that guy.

Are there more factors to the pair’s relative popularity involved? Sure. It’s worth noting that Tim Burton’s Batman hit two years after Superman IV tanked that cinematic franchise for almost 20 years. (Sometimes, the key to taking over a niche is a convenient asteroid that knocks out the competitors.) But the differences as laid out, are, I think, compelling, made all the more so by the lack of intent among so many of the primary shapers of the characters and their dual narratives as they simply tried to get the new funnybooks out on deadline.

The implications, however, are interesting far beyond these two.

In a recent edition of Heat Death, Some Things We Must Let Die, Saul discussed departing Batman writer James Tynion IV’s insightful thoughts on the growth, development, self-awareness, and ultimate autocannibalism of narratives over a sufficiently prolonged period.

As characters enduring through almost a century of continuous serialized publication, Superman and Batman are unique case studies in this regard: ‘first generation’ creations, persisting in a the landscape they both founded and remain central to. Both characters, drawn from shared sources and starting from conceptually similar places, appeared within a year of one another. But like two droplets of water wandering down the course of a stone, their pathways diverged from there. The behind-the-scenes considerations — which character was more initially popular (and therefore significant), when supporting cast and common gimmicks were introduced, what their shared pivot towards ‘family-friendliness’ meant relative to what they had each been doing before — didn’t just result in wildly different characters. They created co-franchises with entirely different conceptual boundaries for what kind of development fan and corporate expectations allowed for.

Not every character or concept can hold down a century-long franchise, though that's not going to stop modern IP managers from trying. But there's a sort of entropy that lurks inside this kind of success [Eds: and everything else.] Any franchise that runs for long enough finds itself a battleground between innovation and tradition, the scletoric hardening of the past that chokes out the new. And crucially, the terms under which that push and pull occurs has less to do with the base ingredients — doomed planet, a mugging in Crime Alley — then the specific circumstances that creators are working in. One of those circumstances, inevitably, is what people believe a story should be.

At some point, people’s expectations for a character or story can end up cramping the kinds of stories you can tell. The Star Wars sequel trilogy, for example, was nothing if not a series of attempts at figuring out “what should Star Wars sequels be?” while navigating successive scales of backlash. The backlash can even become part of the narrative itself. The notion that franchises go so wrong as to require textual repudiation — that they must not simply be managed, but must be seen to be managed — has resulted in the migration of comics-style reboots into mass media. The reset button always looms; once the weight of popular attention falls on a character, fan backlash or corporate nervousness is usually enough to keep their iconography pinned firmly in place.

Our culture is littered with endless recapitulations of powerful and seductive stories. Some go septic and sink back into the mire, scuttled by some essential element deemed incompatible with the demands of the eternal franchise. Others slough off any chains and devour the culture whole. But each and every one of them — like the two World’s Finest who helped kick the whole thing off — must live in the shadow of the ceilings their originators unwittingly placed above their world. Until, one way or another, by tepid reboot or shattered icon, those limits come crashing down.

David Mann blogs about comics on Tumblr and is a contributor to the Action Reaction, a column about current Superman comics. You can follow them @DavidMann95 on Twitter.

That’s Heat Death for this week! Thanks so much for reading. If you like what we do, you can sign up for a membership or tell your friends and family. Up, up and away.

Member discussion