We're All Creatures of Collapse

It hung over them as it hangs over us, as a memory, as a premonition.

The collators of the Bible, in their clay-walled apartment buildings in Babylon; the scribes who wrote down the oral stories of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey; the storytellers who looked forward into a world of gloom and uncertainty, and back into a different world. A time when human beings were more, when civilization had reached its apex in the semi-divine. For all the differences between The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Iliad and the Bible — for all their many thousands of years of accretion and erosion and revision — there is inside them a shared ghost of a past age, an inchoate and half-remembered memory of the world before the priest Kings fell, when people could seriously contemplate a tower to the stars, or look their gods — or God — in the eye.

This is Heat Death, a newsletter that counts the animals two-by-two. Late June finds the Brothers Elbein on the downswing from the solstice, up and itchy and writing at a sunrise that comes far earlier than ought to be allowed.

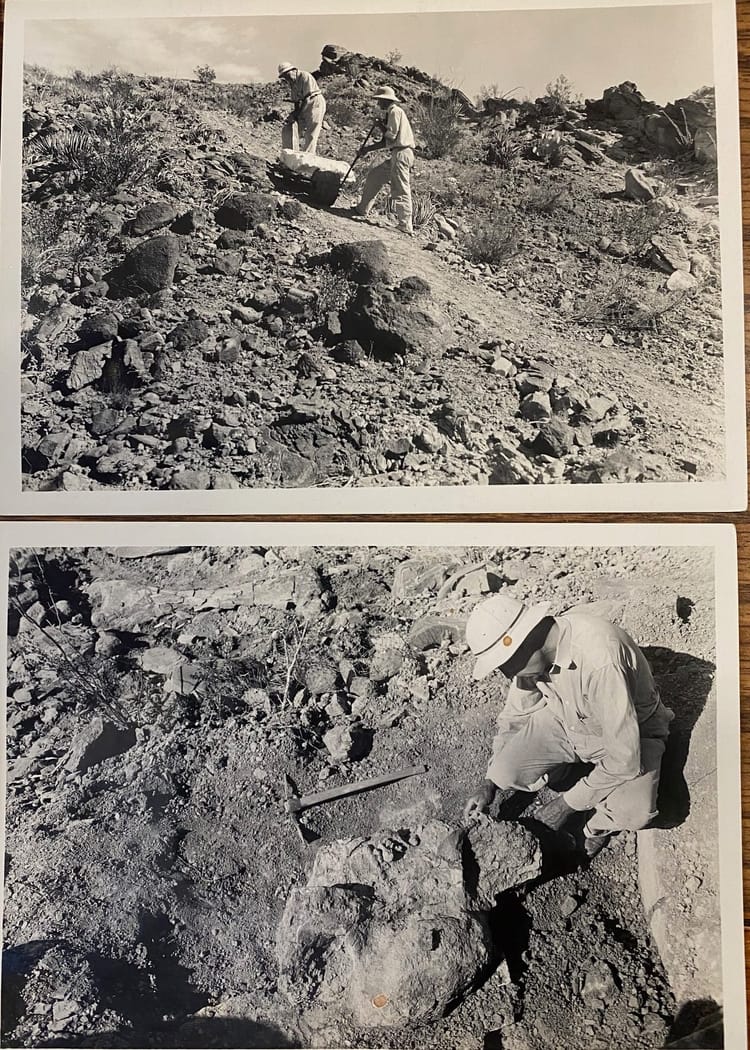

Asher is in Austin, at the edge of the great heat dome cooking the West, wrestling with a book project about the dinosaurs of Big Bend, a foreboding desert that was once the bed of a great tropical shallow sea. Before that sea retreated, it was filled with enormous marine lizards. The swamps and floodplains it left behind hosted a bestiary of dinosaurs; and then, after the end, a host of mammal families struggling to pick up the pieces in a cooler, drier and more volcanic world. (One more chapter to go. Wish him luck.)

Saul is settling in to Equilibrium, the newsletter he is co-running at The Hill. (We have a signup link at bottom.) One of the great challenges of this project, he is finding, is the inherent contradiction in writing about sustainability policy in a world whose underpinnings are so clearly unsustainable. If God themselves had tapped on our forehead with a great invisible index finger and said, “Shape up buddy, or the fire is coming,” our situation would not be more obvious.

It’s easy to get carried away with allusions, to say: We are Sodom, facing fire from the sky in payment for our past actions. Or: We the antediluvian world, watching that crazy neighbor build a boat for a catastrophe that we can still tell ourselves, in the back of our minds, won't be coming. And the notion of prophecy — of disaster foretold long before it strikes — has a disquieting resemblance to our actual situation, where with every flip of the light switch or crank of a window unit, we are committing to a world that is, in the absolute best case, seriously impoverished.

And at worst...

But allusions have their limits, and one such colossal limit is almost too obvious to see. The curators of the Bible, the Iliad, the Epic of Gilgamesh, all lived long after the Bronze Age Collapse that haunted them. They were, in fact, the descendants of its beneficiaries: of the wandering peoples who entered or fought their way into the decaying fortresses of Jericho, Minos, Troy, Mykonos. As in the fairy tale of Humpty Dumpty, collapse is asymmetric — as you cannot run back the tape and put him back together, so collapse swings a door closed on one age, or one civilization’s sense of itself; on its stories and the fragile DNA of its living culture. Whatever you reassemble has been reassembled, and likely by people who never saw the original assembly to begin with.

As a Haida canoe carver, struggling to recreate the lost art of the ancient cedar war canoes, told Saul of their culture’s late-19th Century collapse: “First the masters died, and then the apprentices who knew all they had left to learn,” until all that was left was a great absence where even the memory of what had been forgotten was forgotten.

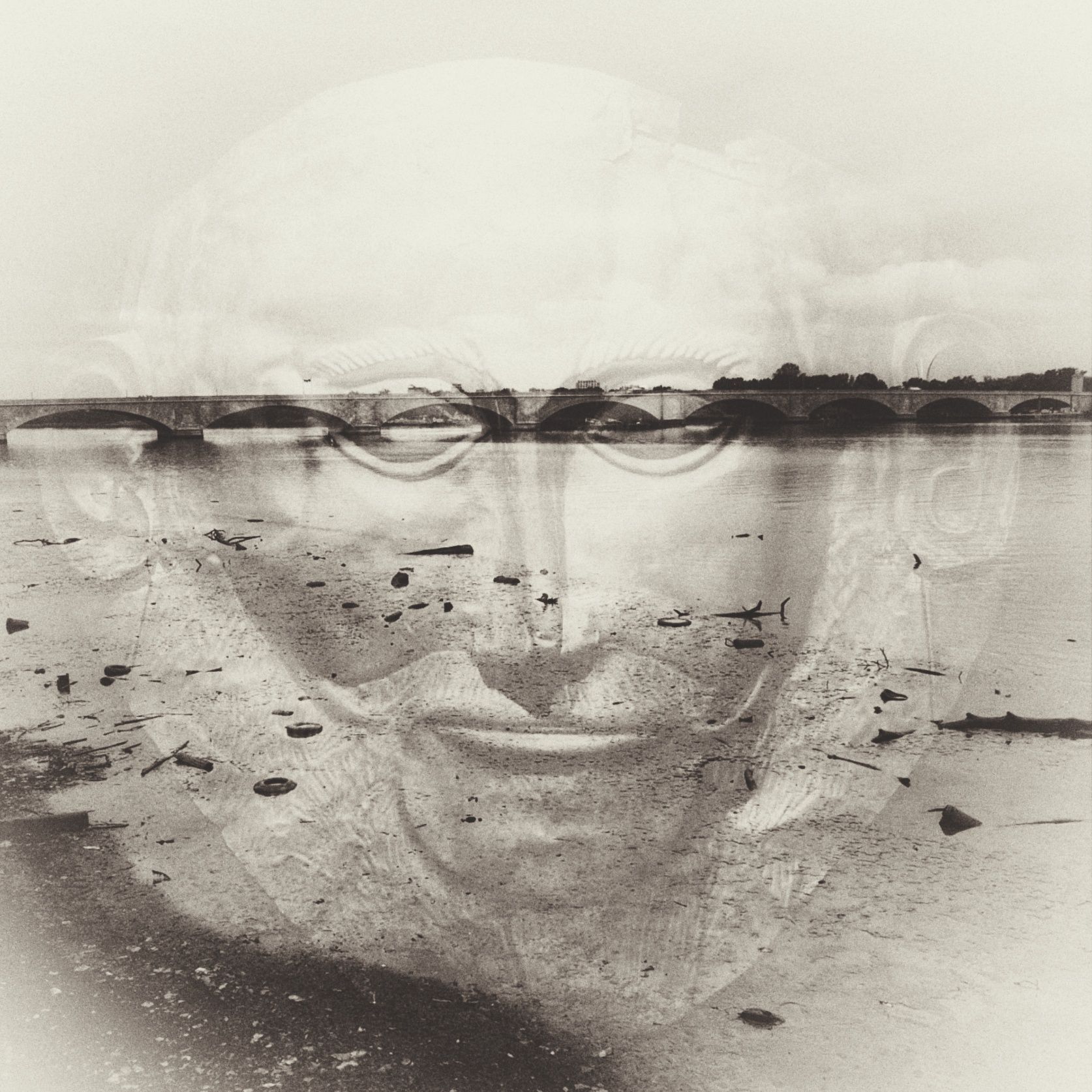

To see artifacts of the age before the Fall — specifically, as Asher will lay out, the great ancient geopolitical extinction event of the Bronze Age Collapse — is to gaze through a historic one-way glass. We can see the artistry and recognize the intent behind, say, a bit of correspondence writing in cuneiform letters on clay tablets. We can see that they were made by people much like us; who if born now would be indistinguishable from anyone else. But they are lost to us. We have only the stories, which are the tales of the shattered survivors merged and alloyed with the new migrants who came among them. Those stories are gilded remnants of a glittering age when human beings touched a kind of glory — we who came after tell ourselves — that cannot be touched again. Their artifacts are a kind of Rorschach test that reveals the dreams that haunt our own souls, in the here and now.

How will they see us, then, our descendants, those who will stand on the other side of another swinging door; who will peer back at us through other panes of cloudy one way glass? What will they say about us, we who were so like the Olympians of the Iliad: powerful and childish, awesome and squabbling? Will they see that we struggled to get the dead hand of our own civilization’s past policies off of our throats — and theirs? Or will we be the squabbling demigods who, for hubris and lack of insight, built a tower to heaven only to watch it fall?

To look at the glittering Mycenaean death mask beneath the Thames estuary above known as the “Mask of Agamemnon” is to understand that we can’t know — we are lost to them as they recede into the future before us. (Not least: we can say pretty surely that it was not, in fact, Agamemnon’s mask.) However it goes, in utopia or dystopia, this civilization — the high-carbon, fossil-fuel belching Golden Age of the post-World War II order — is winding down.

The only question is what waits on the other side.

We’ve got three items for you today. First, Asher delves into the complex nature of collapse, and specifically the Bronze Age Collapse, when — as the conventional account has it — civilization nearly died out in the Mediterranean, clearing the way for the successor civilizations that became our own. (Asher, of course, has questions.) Then, Saul considers the question of whether collapse is too depressing to responsibly write about. And finally, we turn to a future dystopia (utopia?) plagued (blessed?) with Wonderbeasts.

It’s Heat Death. Thanks for joining us.

After the collapse, the past hangs on

Asher here. I’d like you to imagine a world, if you would. A world of tall buildings and planned cities, vibrant technology, elaborate art and artifacts, of commerce and storytellers and mythmakers, fashioning wealth and words from the riches of distant lands. A world of many roads and empires that twined about one another like tree branches, modern, globalized.

And, ultimately, fragile.

Around the 12th century BCE, the great kingdoms of the Mediterranean Bronze Age collapsed. What had been a vast and interconnected tapestry of states splintered.

Before, a Canaanite might buy turmeric, soy oil and bananas from East Asia, where Minoans on the Aegean isle of Thera painted Indian monkeys and Indonesian cloves could be had in Syria. After, the great trading routes that brought Afghan tin to mix with Cypriot copper to make bronze swords in the fell apart. Anatolia, the Hittite cities of Hatusa and Troy — the first known states to use an Indo-European tongue, cousin to our own — burned. In the west, the palaces of the warlike Mycenaean Greeks were demolished. In the east, Babylon fell to successive waves of invaders. In Egypt, the center of the world, the Imperial forces of the New Kingdom rode forth from their cities of the dead to beat back invasion, and ended the war as pale shadows of their old glory.

Climate played a big part in all this calamity, as you’d expect: the Eastern Mediterranean took a steep and sudden turn toward the arid. Rainfall failed; the forests of the Mediterranean contracted; the Nile turned sluggish in its banks. Disruptive new technology spread alongside social unrest. There was a great wandering of desperate peoples, by sea and by land. The Four Horsemen of War, Famine, Pestilence and Death went riding. Things fell apart, the center could not hold, and the world ended.

Or at least, that’s the story.

But let’s check back in. A hundred years after the Bronze Age collapse, the Egyptian Empire is in disarray. The southern lands of Upper Egypt are ruled by the High Priest of Amun, while the Pharaohs hang on in the North. The empire that once held down the Levant is gone.

But that void hasn’t stayed empty. Into it has come the originators of our own civilization:peoples like the Philistines, Edomites, and rising powers like the far-trading Phoenicians, whose seacraft are soon prowling the waters from Syria to Spain, bringing the alphabet to Greece and Italy that is the ancestor of the letters you are reading now. You might say that new systems of trade and commerce are growing in the carcass of the old, like green shoots rising from the decaying humus of a fallen tree. You might also say that people still need things, and are willing to walk or sail — or pay someone else to walk or sail — in order to get them.

One clue to that recovery lies in a paper that came out last week from The Journal of Archeological Science, where archeologists describe four bronze funerary icons from 1010 BC, uncovered from Tanis, then capital of Pharaonic egypt. The icons are ushabtis, stylized little figurines of mummies meant — by processes of sympathetic magic — to act as servants in the land of the dead. (The names of their masters and mistresses are stamped on them, which also makes them extremely handy for dating tombs.)

Bronze, if you don’t recall, is an alloy made primarily of copper (the remaining 10% being that formerly Afghan-derived tin), which also tends to have naturally occurring bits of lead. By studying the lead isotopes in the figurines, researchers were able to trace where the copper came from: thriving copper mines in the Arava Valley on the modern southern border of Israel and Jordan.

Egypt did not, at this point, run these mines; it’s still not clear who did. What is clear is that Pharaonic Egypt was importing valuable metals across hundreds of kilometers of brutal desert, and doing so fairly reliably, to boot. In fact, the Pharaohs' hunger for Arava copper seems to have kicked off a renaissance of metal art in Lower Egypt.

“After believing that Egypt is isolated and sinking into its own world, we now understand there was an international exchange network and that Egypt was part of it,” one of the researchers told Haaretz. “We like to think of this ‘dark age’ as the opposite of the late Bronze Age, with its high degree of interconnectivity, but now we see that there still was interconnectivity, just on a different scale.”

This should not surprise us. The Mediterranean and European world of 1000 AD — often popularly called the Dark Ages, the time after the Western Roman Empire finally dissolved — was itself a globalized and connected one. As historian Valerie Hansen writes in her fantastically clear and entertaining The Year 1000: When Explorers Connected the World—and Globalization Began, the spiderweb threads of trade stretched from the stark lands of the Baltic to the opulent courts of the Song Chinese, where Norse ships may well have blundered into Mayan waters and the spoke of global society were the teeming emirates and empires of Muslim West Asia.

There were people in those days who remembered, vaguely, that once Rome had knitted the Mediterranean together, and that something had been lost. But endings are often artificial constructions, imposed after the fact. You have to pinpoint, among a tangled web of causality, a state change. You have to put your finger on where this becomes that, a process which reveals more about your definitions than the facts on the ground.

Every story begins in the last story, and every story suggests its own sequel, and crucially, they’re all part of the same chain. Coastlines of ancient seaways presage modern voting patterns; Plato and Aristotle’s ideas about the hierarchy of life were adopted by Christian thinkers and haunt evolutionary theory to this day. Rome falls; Babylon falls; people move on into a new world with roots in the old. Much is lost. But you'd be surprised at how much sticks around.

Interlude: Is it responsible to discuss collapse?

Saul here. I received my first piece of hate (fan?) mail early this morning, in reference to a monstrously sad item we ran Tuesday in Equilibrium, about a container ship that burned and sank off the coast of Sri Lanka a couple of weeks ago, wreaking havoc on the coastal ecosystem.

In one way, at least, we’re like the peoples of the Eastern Mediterranean Asher writes about above, on both sides of the Bronze Age Collapse: a civilization tied together by maritime trade. On any given day thousands of enormous container ships are plying the ocean, carrying cars and corn and copper but also, of course, caustic and flammable chemicals.

We don’t know yet what happened to the X-Press Pearl — at least, not in the autopsy sense. We don’t know the precise means by which the ship caught fire, broke up, and sank into the shallow, fecund waters off the shores of Sri Lanka during the height of the sea turtle migration, killing a dozen dolphins and hundreds of turtles.

But, as my letter-writer reminded me this morning, in the macro-sense the cause is obvious: “We let the oceans of the world become industrialized shipping routes and are suddenly awakened by disaster. Every one of those ships is deadly, and this cavalcade of stupidity and greed just may be the nail in humanity's coffin.”

Leaving aside that the dead are, largely, not human — therein the tragedy — there is a peculiar sort of knowing cynicism, the climate scientist Michael Mann (and others) has written, that is in fact a soft form of climate denial. It’s as though there is a binary flip, characteristically (though by no means exclusively) found in Boomers and Gen X: a kind of “well fuck it, we’re doomed” response to news of environmental tragedy or fossil fuel revanchism that passes for acceptance but is, in fact, the equivalent of a child sticking their fingers in their ears and going “La la la I can’t hear you.”

The letter writer goes on: “Will anything come of this particular incident? Nope. International trade is too important to be tampered with. Thus the sort of journalism you practice does little but frighten and depress the general public already sick to death with such terrifying news.”

To which we at Heat Death say: Look. These are scary times. An age is ending. Yesterday we ran a long item about a leaked U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report that predicts 80 million starving by midcentury and 120 million (likely including a lot of those 80, or those who don’t wish to join them) on the move, looking for anywhere safe. Rising heat will kill corn and rice across much of their range, and rising carbon levels will lard the rest with empty calories, just like the microplastics that coat the guts of ocean-bottom filter feeders, giving them bulk but no nutrients. Glaciers and freshwater aquifers that billions depend on — including, possibly, you — are falling back.

And as they do, and as the world’s civilizations face an ever-more-restricted ecumene, chaos and instability are going to rise, battering against the walls of our existing political system and likely — in places, or in whole — overwhelming it. We are facing a new age of heat and famine, war and migration. The shimmering event horizon that Asher and I refer to as The Bottleneck.

But it is irresponsible — a form, I’d go so far as to say, of desertion or treason in the face of the enemy — to see that and quail. In calling for a Green New Deal, progressives like to compare the national effort needed to face the coming storm to the great government programs of the 1930s, and the global liberal-socialist war against fascism.

In the interest of argument, then, let’s take the analogy further: To sink into despair is analogous to becoming an America Firster as Hitler knocks through the democracies of Europe. It is to look at the greed and cowardice of Munich, the ignominious fall of the Spanish Republic, and say, “Oh well, there’s no point, democracy had its day, but in the modern age …”

I am sympathetic to the line that leads to, ‘Ah well, we’re fucked, so let’s get fucked up.’ But I don’t buy it. And I think it cosplays as being serious and sober analysis while in fact being a kind of light depression — a symptom, perhaps, of the lack of clear political leadership in steering through the bottleneck, and the lack of apparent urgency in the world’s liberal states.

Despair is, in the end, a kind of “presentism:” the person who sits in an air conditioned house in a reasonably stable nation-state with ready access to resources, fantasizes morbidly about when it will all be taken away, and when God will come and judge us all for our sins — as slaveholders in the antebellum South once fantasized morbidly about the looming slave revolt that, in the quiet of the night, they must have seen as their just and inevitable deserts.

To take that analogy further, you can gas gloomily about the coming collapse — to call it the inevitable payment for America’s sins — while going about your business. Or you can be a hopeless weirdo working for abolition. In this sense, “eh, we’re fucked” is an abdication of responsibility carried out by the comfortable and inflicted on the unborn.

You have to live through the collapse you think is inevitable. Civilization will not flick off with the touch of a light switch; wherever we go from here will be a slow, agonizing transition, and the Fall, if it comes, will be protracted and painful, leavened by brief false notes of recovery and retrenchment before the slide resumes.

To the doomers we say: the day is perhaps coming when your windows will be shattered and the a.c. turns off — not in some distant future, but to you, yourself.

The question is: what do you plan to do about it? We can save ourselves only collectively; individually, we will be flooded out in our little fortresses by a figurative or literal rising tide. So are you going to join us, or are you just going to complain?

We are, as in Cormac McCarthy’s devastating apocalyptic The Road, carriers of a fire that predated us and will, we hope, outlive us. Let’s do our part to carry it into the future dark.

Don't Fear The Creature

Asher again. That's all fairly grim, so let's change tack a bit. Sometimes, a piece of media comes along that is so bizarre, so singular that you can’t help but stare at it. On Wednesday — the day that an IPCC draft report suggested that the world may be locked in for three degrees of warming, and a weather forecast predicted a brutal triple digit heat wave in the Pacific Northwest — Netflix dropped this trailer.

The show is Sexy Beasts, a dating show where conventionally attractive people are — by dint of the magic of prosthetics and makeup — transformed into inhuman creatures, with the ostensible goal of seeing whether personality can matter more than looks. (“Ass first, personality second,” a beaver remarks.)

It is an arrestingly strange document: there is perhaps no other time in American culture that could have produced such a thing. Amid a time of great revelation, the show piles on more elaborate masks and spectacle, a dance of veils around a central promise—that at the end, the masks can be pulled off to reveal a conventionally attractive human. It’s an invitation not just to fuck around, but to find out. It is — in the literal sense of the dropping of veils — apocalyptic.

But blending the human and animal in times of crisis is a grand tradition. Take, for example, another Netflix show that wrapped up last year.

It begins in a striking smash-cut transition: there is a city of skyscrapers, and then they are rubble and forest, huge and twisting trunks shouldering aside all the works of man. Water thunders out of a pipe and deposits a 12 year old girl from some underground community into a broad drainage ditch. She doesn't regard this new surface as normal (the vegetation is huge! The bees dubstep! The wildlife is massive and multi-limbed!) She almost immediately connects with other roving human scavengers and mutated animals. As it transpires, she's not totally normal, either.

Netflix's Kipo and the Age of Wonderbeasts is, in broad strokes, a story that can be traced back to the atomic fears of the 1970s, when the novel (and a massively popular film adaptation) Planet of the Apes dropped a modern astronaut onto a world of "lower" primates.

The apes of that titular planet live in a species-based caste system, with Gorilla Warriors, Chimp scientists, and Orangutan priest-kings, all of whom regard humanity as pets at best and livestock at worst. Yet humanity's own foibles and sins are refracted through them into new patterns, as unsettling for their familiarity as their strangeness. And, of course, the kicker is that this alien world isn't so alien after all. Mankind authored its own destruction, and what followed was unable to rise above the legacy we left behind.

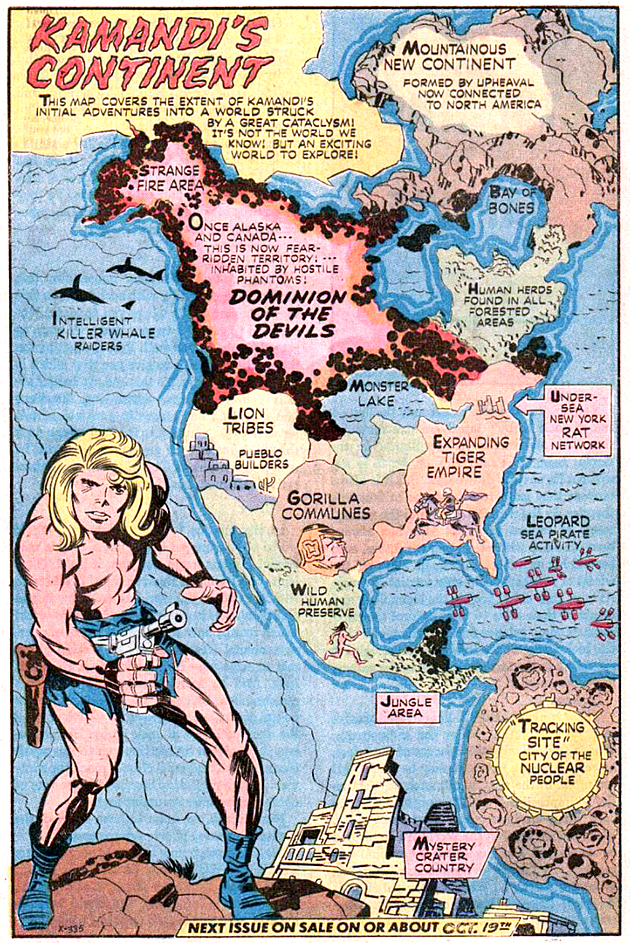

Planet of the Apes was influential enough to directly inspire not only a sprawling franchise (and a Hollywood fad for atrocious knockoffs) but also the DC comic Kamandi, a creation of the great Jack "King" Kirby. Kamandi followed the adventures of the "Last Boy on Earth" as he left his underground bunker and ventured into a world of warring animal nations, made up largely of intelligent wolves, tigers, leopards and dogs.

As Elle Collins notes in their great piece on the comic, "Kamandi, to borrow a phrase, is the last of us. He's not technically the last human, but he's the last human who looks at the world he's awakened into and sees it as bizarre and wrong. Even if his knowledge comes only from history books pored over in an underground bunker, he expects the world to look like ours, and reacts with the same surprise we would to what it's become."

If the genre must be called something, call it the Post-Apocalyptic Animal: a world where some great disaster has flipped the relationship between man and beast, tearing away the masks of civilized, Enlightenment humanity and leaving animals with the upper hand. In this genre, nonhumans become satiric stand-ins for many of our worst or weirdest impulses. The apes of Planet of the Apes are superstitious, religious zealots with a restrictive caste system and a society struggling to rise above its own civil rights abuses. The animal nations of Kamandi are largely warlike: kingdoms and pirates and bandits and empires, forever at each other's throats. All of them wear the costumes of a dead era, endlessly re-litigating the old human ways: more intelligence, these stories suggest, more problems. There's rarely any sense that whatever comes after us might be able to forge a different society, much less a better one.

In Kipo, the animal peoples — while nominally dangerous — operate more along the lines of random American subcultures. There are lumberjack cats, head-banging rock snakes, Top Gun-style hummingbirds, 80s exercise raccoons. All of this is played more or less for absurdity. Yet the idea of animals representing human foibles remains: the main villain is Scarlamagne, a well-dressed mandrill (an ape, naturally!) who refers to humans as “lower primates," and who dreams of conquest while dressing himself and his human slaves in the decadent fashions of a French court.

All the animals in Kipo are playing dress-up to some degree, but only Scarlamagne seems to be doing so deliberately, reaching for some sort of deeper legitimacy. It's all a bit self-conscious as villainy goes, which perhaps is the point. In a different story, the villainous ape yearning to set himself above mankind might be a commentary on the essential difference between man and animals, a subtext often deployed in racialized ways. (“I wanna be like you-u-u.”) But Scarlamagne is people, for all intents and purposes. Everyone in the show is.

Let's keep our eye on that, for a moment: everyone in the show is people. Animals wear human clothes: humans like the taciturn and tough Wolf wear animal skins; there is less of a divide than a blending, a mixture of categories. It is a view familiar from Indigenous cosmologies, with humans as one people among a multi-species confederacy of animal peoples — what the philosopher Sue Donaldson, in another context, called the Zoopolis — where animals can shed their skins and marry us, and we can don their furs and lose ourselves in them. While Kipo doesn't suggest that the animals have built a better world than humanity did — this genre never seems to be able to make that conceptual leap — it does suggest that if animals are people, then people are just another sort of animal, and maybe we should all just try to get along as best we can.

If anything, Sexy Beasts embodies the reverse. For all that the premise seems to orbit the question of whether you can love that which isn’t immediately attractive — which isn’t precisely human — the point of the exercise is to take the masks off, and set the world right once more. See? They were really a sexy human person all along. The lady is not a panda; the man is not a minotaur; the lawyer is not a cat. . "If you think I come hither as a lion, it were pity of my life," cries the hapless thespian in Midsummer Night's Dream. "No, I am no such thing. I am a man as other men are.”*

The Post-Apocalyptic animal story doesn't hold with that nonsense. It's about what happens when the masks come off, and we discover that what lies beneath is just as — forgive me — furry. It’s not always a happy genre: Planet of the Apes looked at a world seemingly on the brink of nuclear war and issued a bitter warning. But Kipo greets the idea of a reordered world with an enthusiastic bounce, and the suggestion that revelation’s a poor substitute for empathy. Like the Blue Oyster Cult (almost) said: Baby, don't fear the creature.

ELBEINS ABOUT TOWN

Asher wrote about some good news, for a change: a piece for Audubon following up on the fate of the Attwater’s Prairie Chicken, a deeply silly and desperately threatened bird of the Texas Coastal Prairie. After a succession of climate disasters devastated the reintroduced population, the birds have caught a break and are beginning to get their numbers up from “basically extinct” to “severely endangered,” which is no mean feat. You can read more about that here.

After two weeks of practice runs, Saul’s newsletter Equilibrium went live on Monday; you can read a sample issue here, and (if it doesn’t prompt you when you click) subscribe here.

This has been Heat Death. See you all next week.

Member discussion