Consuming Across Categories

About 200 years before Columbus landed at Hispaniola, another set of seafaring settlers arrived at a pair of long, jutting volcanic islands that their descendants called Aotearoa. An even later set of shipborne settlers would call it New Zealand.

It must have seemed like a true New World. For unlike the English — who imagined a blank slate atop the rich and densely peopled histories of both Australia and North America — these ancestors of today's Māori people landed their outrigger canoes on the shores of a miniature continent utterly devoid of humans.

Instead they found a rich ecosphere of enormous ancient forests patrolled by a complex bestiary of birds, including enormous eagles and moas, among the largest dinosaurs to have coexisted with humans.

Armed with a battle-tested kit of sophisticated weaponry and the full gathered power of the Polynesian crop complex, the colonists took to this new world — and began to devour it.

Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that knows what kinds of exciting culinary possibilities exist once you muscle past the gag reflex. Mid October finds the larger Elbein clan in the midst of a complicated triangular movement.

Asher is in Atlanta, at the start of a series of writing retreats that he hopes will soon spit out a working draft of a new Anna O’Brien novel — while also holding down the house for their parents, who are visiting Saul and Anush at the DC Soviet, who are themselves preparing to complete this complicated balancing act by a move back to Austin, Texas early this winter.

It’s all a bit messy. So today we’re looking at two different myths that keep our understanding of the world tidy — and at the places where those neat categories spill over the borderlines, giving us a glimpse into the dizzying chaos beneath.

The first myth, which we began building up to in the intro, is the persistent idea that ecological history can be divided neatly between a Edenic pre-industrial past in which humans lived relatively lightly on the landscape and left minimal traces — and the disrupted era of the past 200 years, when fossil fuels began an entirely different period, often called the Anthropocene.

The second myth is one we all learned in grade school: that all animal life divides neatly into either herbivores, carnivores, with the large mushy borderlands of omnivores in between.

As an organizing framework for looking at the world, both of these myths work pretty well: they are good heuristics, or rules of thumb, for understanding an underlying world — the human/ecological record, the panoply of species behavior — of otherwise mind-bending complexity.

And yet myths they both are. And as in so many places, if we look at the frontiers where these categories come together, we find a disputed and unsettling borderland that can teach us a great deal about how the world actually works.

The theme for today's newsletter is omnomnivory: a word we just made up for that which eats — with gusto — across the categories that are supposed to contain it.

It's Heat Death. Stay with us.

The Pristine Pre-industrial Age Is A Myth

Saul here. Our first story starts with a minor mystery. A few years ago, a multinational team of Antarctic scientists found something unexpected in the ice cores they were studying from James Ross Island: an increased presence of soot which started around 1300, peaked in the 1600s, and continued until the present.

To refresh your memory: an ice core is a long vertical column of ice. They’re the product of centuries of snow, which itself has crystallized out of and fallen from the atmosphere — making ice cores excellent chronological records of the state of the atmosphere at any given time. Soot, meanwhile, is the powdery byproduct of combustion: “black carbon”, the heat death of wood or fossil fuels, carried aloft on the thermals rising from fires and smokestacks to coat the insides of chimney flues or the outsides of Victorian cities.

So what, the scientists wondered, was it doing in the ice off the coast of Antarctica, a continent utterly devoid of human presence and thousands of miles from the nearest inhabited islands?

The scientists worked backwards like detectives. Soot meant fires, which in the 14th Century could only mean burning trees; by atmospheric modeling, they determined that prevailing weather patterns could only have carried the soot there from Patagonia, Tasmania and New Zealand.

And when they cross-referenced this against the paleofire record in those places — a record of ancient burns laid down as layers of charcoal — they found that only one location had a massive uptick in burning: New Zealand, which in 1300 had, by no coincidence, just been yanked into the larger global network of human settlements by the arrival of the Māori.

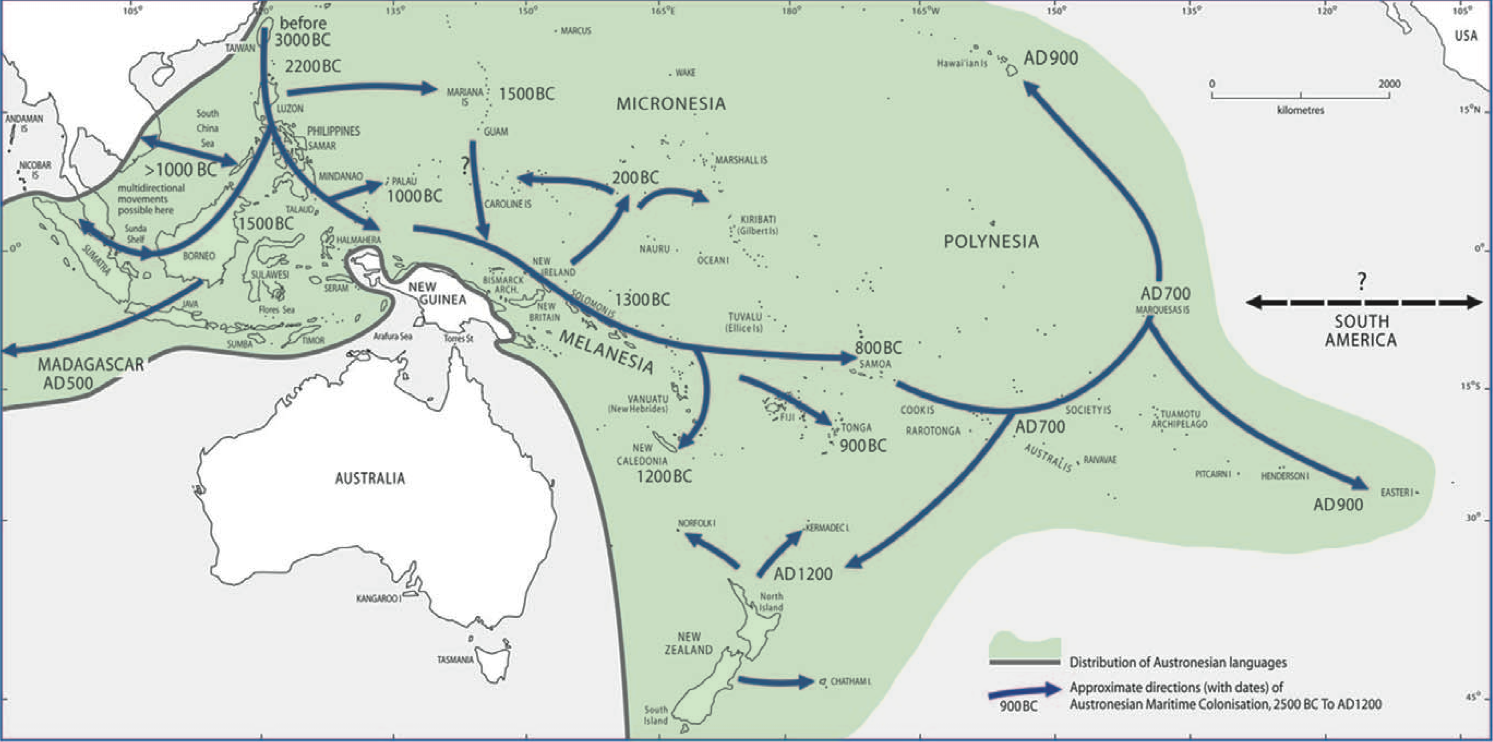

The Māori arrival on Aotearoa was the end-point of a breathtaking, millenia-long island hopping expansion by the Polynesian peoples — an apparently planned multi-wave settlement effort, carried out in great double-hulled voyaging canoes, or waka hourua, largely between 1320 and 1350.

There’s a reconstruction of one of these canoes here — they are staggeringly impressive vessels, the culmination of a seafaring culture that had reached a level of competence, confidence and institutional knowledge that allowed for large-scale colonization across thousands of miles of open water using a Stone Age toolkit.

When the Māori got to the islands, they did what pre-modern agricultural peoples did all around the world, and what many still do: they burned like crazy. Today, in places like the Maya regions of the Yucatan, fire is commonly used in agriculture as a kind of tractor, wiping a field clean of stubble and preparing it with a layer of nourishing carbon.

It is very difficult to chop down a tree with stone tools, as the author Charles Mann has detailed in 1491 — you have to almost pulverize the trunk into pulp, rather than the precision blows of a metal axe— and in an ecosystem dominated by trees, fire helps to keep the forest from coming back once you have painstakingly removed it.

But it was the scale of that Māori fire that shocked the scientists, who wrote up their findings in Nature: a massive expansion in population and land cultivation so large that it left a record in ice cores 4,500 miles away.

Joseph R. McConnell, the study lead, laid out why that was surprising. "We used to think that if you went back a few hundred years you'd be looking at a pristine, pre-industrial world,” he said. “But it's clear from this study that humans have been impacting the environment over the Southern Ocean and the Antarctica Peninsula for at least the last 700 years."

What’s dramatic about this example is how unlikely it was that we would even find out about it. Prevailing winds had to carry the soot to that precise area to be deposited in snow. Scientists had to find the ice cores and notice the soot. They had to devote the time and resources to studying it, had to get funding and avoid the blind alleys and the personnel disputes by which research projects often break down, leaving potential intellectual treasures to remain hidden.

All of which is to say: if I was going to bet, I’d wager this case is more the exception than the rule. That human manipulation of the landscapes by means of fire is an ancient and pervasive technology, one that goes back far further than any historical record we have. That perhaps to be human is to be a creature who—like beavers on methamphetamine—are distinguished by the need to deliberately reshape our environment.

It also suggests that the division McConnell suggests, and that we set up in the introduction—between the “pristine, pre-industrial” world and the coal-driven machine age we now live in—is far blurrier than we commonly think.

The word “industrial” has become a shorthand for factories, engines and fossil fuels. But you can have large scale, systematized mass production without any of those things: you can do it all with fire. In a Tides of History podcast on the emergence of cities in the Bronze-Age steppe, Patrick Wyman suggests that they began as the descendants of herding peoples began to cluster in forge-towns clustered near the copper deposits necessary to make bronze alloys: centers of mass-produced weapons and tools.

These towns would have been tiny by modern standards; the weapons made by families or groups of artisans working by hand, not in great factories driven by one enormous motor. But their skies would have hung heavy with a fug of smoke and aerosolized metal, in an environment far more reminiscent of some 19th Century satanic mill town than the pre-industrial harmony we tend to expect.

An even clearer example: the same team who did the Antarctic study also found that the concentration of particles of lead in the Greenland ice sheet — on the other side of the globe — served as a clear proxy for late-Roman economic activity, since aerosolized lead is a key indicator that people have been smelting silver on a large scale. In times of economic expansion, lead concentrations in the ice go up; in times of plague and collapse, they go down.

In the heart of Europe, ice cores from the deepest crevasses of Mont Blanc, in the Alps, show stark spikes in atmospheric lead and antimony pollution in 200 B.C. and 200 A.D. Both accompany the expansion of Roman factory towns that produced the lead piping undergirding the empire's urban plumbing, as well as the increased production of silver and gold.

Recall that Rome itself was also home to cities of tens of thousands of people, all constantly burning wood and charcoal — and that Rome was just one of many large, complex pre-modern states — and we end up with a picture of a “pre-industrial” Europe riven by enough industrial and environmental pollution to approach that of the Industrial Revolution: a vision of a past unsettlingly close to the present. “What happens is far beyond the work of giants,” Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder remarked of the ruined, fractured landscape of the Las Médulas mines in Spain, with its polluted air and eroded hulks of slope. “How dangerous we have made the Earth!”

What do we do with this? At Heat Death, we take it as a warning against romanticizing the past. The vision of the “pristine pre-industrial world” is a seductive one, but it’s also dangerous. It covers up the fact that the greatest engine of change to the biosphere has not, historically, been the Machine Age but the slow, low-tech, often-valorized expansion of land-clearing small farmers — or the uncomfortable fact that the largest contributor to the global expansion of forests over the last century has been a fossil fuel boom that pulled smallholders from the land. This division between good past and bad present leaves open the possibility that if only we could return to some lost Eden, we could live again in balance with nature.

But there is no going back. In the myth of Prometheus, the titan is punished for gifting humanity the god-fire — the ability to create and reshape that the Olympion Gods had claimed for themselves. Along with that gift, it seems, came a cost: that humanity would be continually forced to reckon with the destruction that comes alongside our greatness, forever forced to mitigate or reduce it.

However the fossil fuel age may have raised the stakes, this paradox isn’t inherently modern. It t goes to the roots of being human. Balance is an equilibrium to be sought in our future — to find our way into, fall out of, and find our way back to — rather than a blessed state we left behind in our prelapsarian past.

I don’t know if that’s comforting or disturbing. I do know, however, that whatever there may be to learn from traditional cultures past and present, the way out of our current predicament won’t be found in longing for an imagined better world that has in any case vanished. From here, the only way out is through.

Heat Death continues after the jump, with a truly shocking revelation about the culinary habits of tortoises. Stay with us.