I Met A Traveler From An Online Land

The city had been dead for over a thousand years when we arrived. Humid air washed over us as we climbed from the rental car, the dead-leaf smell of the Guatemalan rainforest thick against our noses. It was December 2015, and we were at the tail end of a family vacation to Guatemala, one that had seen us travel from the mountain stronghold of Xelajú to the Caribbean coastal port of Livingston. We decided to finish the trip with a visit to Guatemala’s most famous landscape: the city-swallowing jungles of the Petén, where the bones of Classical Mayan civilization had been carefully exhumed from beneath centuries of forest.

There are places—Rome, Istanbul, Baghdad—that have been continuously inhabited for thousands of years. These are cities defined by a constant, living churn: their occupants busily building and rebuilding and scavenging and stealing, until the history of the place bulges and ripples beneath the skin of the present.

But there are also cities who have been abandoned, sometimes so thoroughly that their very location has been lost from memory. We call these “lost cities,” but a better term might be “rejected cities” — the places where people decided, for whatever reason, to abandon the whole urban experiment.

The rejected city we had come to see was called Yaxha. Once it had been the capital of a powerful state that alternatively traded and warred with the great (and similarly rejected) metropolises of Tikal and Calakmul.

Unlike those tourist-beloved cities, we had the trails largely to ourselves. We walked along broad, straight canyons that had once been city streets; through forest groves that sprouted over plazas and reservoirs; past lumps of hillside that concealed the half-digested ruins of stone houses. The only sounds were the birds, and the grunting roar of howler monkeys foraging through the tree-tops.

What happened to this place, where traders once swapped goods from the Pueblo lands of the desert Southwest and the Mexican peoples, and priest-lords sat above ceremonial ball pits, glorying in the roar of the crowd? Why was it rejected?

We don’t precisely know. We do know that sometime in the 9th century CE, after years of prosperity and growth, some mixture of ecological, climatic and cultural troubles led to the states’ collapse. The centrifugal power of the cities over the outlying villages waned beyond repair. Their centralizing gravitational pull faded, then failed. And the people who lived there made a practical decision and went off to do other things, somewhere else.

Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that refuses to forget the glory that was Geocities, the triumph that was Tumblr.

But to catch you up: the Brothers Elbein have been busy walking their assigned beats. Saul has been nose-to-the-grindstone at The Hill, where his Equilibrium newsletter remains a daily shadow-history of our collective struggle to stay afloat on this warming, worsening world. He’s written recently about how Hurricane Ian helped Ron DeSantis’ win; why Brazil’s presidential election should give us cautious new hope for the Amazon rainforest; and how fire and flood are working together to threaten the water supplies of Western cities. (And as a bonus: why Hurricane Ian led to a rash of spontaneously exploding Teslas.)

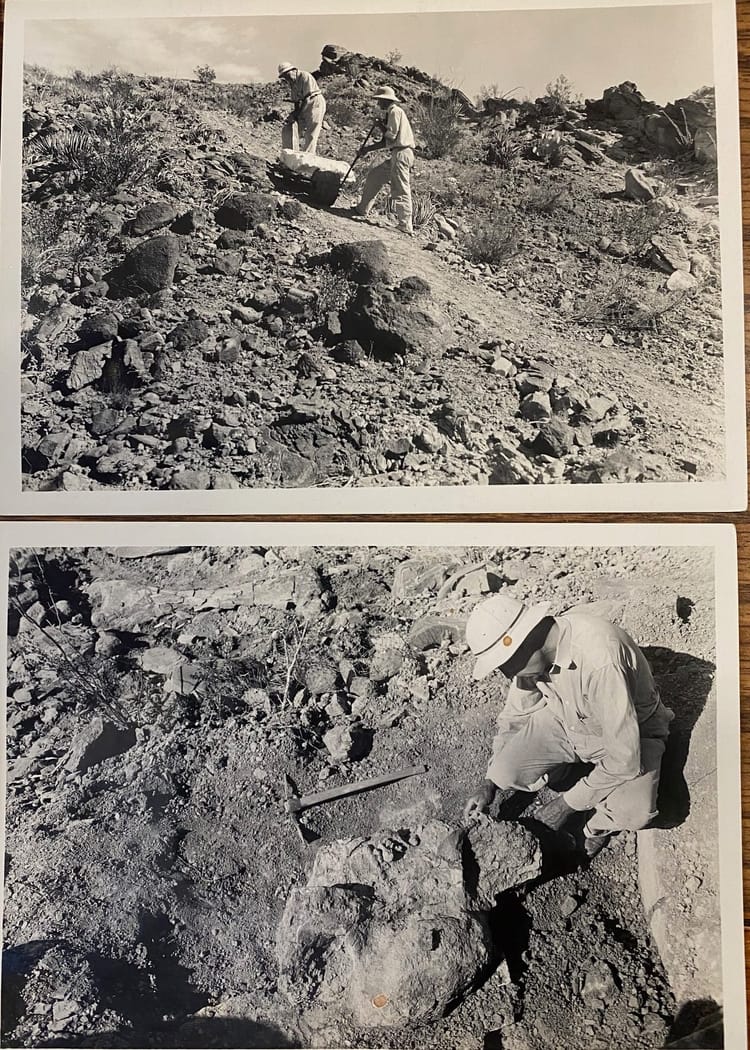

Meanwhile, Asher has been cleaning up his long-term assignments. (Much of his recent work is months away from being published — magazines work on long time tables — but you’ll hear about it here as soon as it’s done.) He’s also in negotiations with a publisher about a new book project, which will cover the vast, wonderful world of Texas paleontology. That, combined with the in-progress Anna O’Brien novel 16 Tons, means that 2023 is shaping up to be an exceedingly busy year.

Today on Heat Death, we're thinking about abandoned places, including ones that can be just as vibrant, alive, and ultimately just as ephemeral as Yaxha or Tikal. We speak of the ghost cities that remain where once-vital internet communities once hummed. The echoing wasteland where people once strutted, courted and explored new possibilities — now gone, gone, gone, their digital corridors left without even the echo of an explorer's footfalls.

This is Heat Death. Stay with us.

Look on My Posts, Ye Mighty, and Despair

Asher here. If you’re on Twitter—and realistically, even if you aren’t—you probably heard that billionaire and human-shaped meme Elon Musk bought the website a week or so ago.

It was the kind of purchase that was nearly indistinguishable from a scam, albeit one perpetrated on one of the world's easiest marks: a staggeringly ill-conceived $44 billion-dollar deal that went through only after Musk spent several months trying to wiggle out of it. (As well he might have: Twitter was massively overvalued, and he bought it by means of a loan with an annual interest rate 50% higher than the sites’ annual profit.)

The events have unfolded like a soap opera set on fast-forward, but there is a pleasure in recounting them even if you know the steps. Musk came in with extravagant promises about free speech, and then rapidly began banning people who made fun of him. He announced that verification—previously restricted to notable people, i.e celebrities, authors, journalists, etc—was now available only to people willing to pay 8$ a month, before changing his mind several times and settling on an option that was, somehow, worse. He fired a huge swath of Twitter’s staff, triggering an immediate lawsuit in federal court. And then — as it became clear that the staff he had filed willy-nilly actually kept the site online — began asking some fired staff to come back. The site’s infrastructure is corroding with impressive speed, and worse is likely to come. Perhaps as many as a million users have fled.

It now seems likely that Twitter’s role as a genuine town square of news and conversation—however toxic—is in serious danger of being ruined by one of the tech industry’s most genuinely idiotic men. (A man, let us recall, whose entire status as the world's wealthiest man relies on his supposed business acumen at the head of his three other companies.)

As innumerable commentators have pointed out, what happened to Twitter is the sort of thing that can only happen in the current social media landscape — a relatively recent phenomenon which pulled together the ragtag, distributed internet into a handful of centralized platforms, as dominated by a few massive companies. This is a fair point, and points out a genuine problem. But let’s not forget: those giant companies are also having a bad time. As internet journalist Ryan Brodrick notes in his newsletter Garbage Day, Facebook has been steadily losing users. The site’s parent company, Meta, has been absolutely hemorrhaging money in its attempt to build a VR framework that people are staying away from in droves: yesterday, the company fired 11,000 employees, around 13% of their staff. YouTube’s ad revenues are is slowing down considerably. And Instagram has seemingly dedicated itself to infuriating longtime posters via a procession of algorithm changes, largely in a (failing) effort to keep up with Tiktok. The latter is pretty much the only centralized social media platform currently seeing any success, Brodrick writes, “and it’s closer to Netflix than it is Facebook.”

But then, when was the last time you got on Facebook? There are definite limits to nostalgia here—the website was always a privacy-destroying, data-mining trap—but there was a time (not so very long ago!) that the lure sparkled and the hinges were well-oiled enough that you barely heard the teeth snap shut. There was a time when it was indispensable because it was truly a community; deftly woven into the social and sexual lives of virtually all Millennials in a way that nothing else has ever been, before or since.

Facebook lured you there (lest we forget) with the presence of something real. Real friends, real people you wanted to keep in touch with, converse with, argue with, flirt with. It kept you there with the regular dopamine-drip of notifications—a nearly-concrete distillation of the sense being seen, being noticed. An addictive blend of genuine and simulated interactions.

But with the passage of time and relentless growth, Facebook — the website — basically no longer works. It's not precisely defunct, but to walk its digital corridors today feels like visiting any of America's many decaying suburban malls: a place hanging on to just enough life to be depressing.

The site also serves as an object lesson in how the walled-garden and town-square aspects of the modern social network combine to create a hybrid that accomplishes neither goal. Facebook is terrible for both discussion and self-promotion, because its algorithm buries outside links — the main thing that makes online so different from reading offline —in a desperate attempt to keep you from leaving the actual website. (Which, for me at least, means that there’s less and less reason to actually visit it.) Events—one of the most useful aspects of Facebook—have also been massively de-prioritized after Covid, with the result that people don’t see invitations to them, which makes them basically useless. Navigating to new comments is similarly difficult. Somehow, despite the fact that I barely use the site, my notifications tab is always full of messages that have nothing to do with me—missives informing me in various ways that someone is interacting, somewhere, and warning me that I might miss it.

In other words: the mechanism for keeping me engaged has rusted so badly that the snare has become obvious. The usefulness is gone, and only the vestigial hook remains — seductive only to those too old or internet-unsavvy not to see that there is no cherry on the other side of the red dot.

Part of this may have to do with Facebook’s continual pursuit of growth, its desire to make itself both a self-contained world and the central hub of the internet. (It turns out it’s very difficult to be both, especially when you realize who you’re actually walled into that garden with, as the past four years have made painfully clear.) But another aspect of the decline lies in the creeping sense that Facebook—and other social media sites—has begun to lose contact with reality itself.

Over the course of the 2010s, the hegemony of Facebook induced many digital media operations to reorient themselves around the site: it was, after all, where the audience was. In 2016, Facebook executives—including Mark Zuckerberg—began actively cajoling media publishers into creating videos for their Facebook pages. Their data showed that such videos performed like gangbusters, bringing in more eyes and more advertising money for everyone concerned. Digital publishers like Mic, Vice, and Mashable bit, and began laying off journalists in a now-notorious“pivot to video.” These layoffs, which occurred with metronomic regularity throughout 2017, were accompanied by statements like the one delivered by MTV News, which announced a shift toward “short-form video content more in line with young people’s media consumption habits.”

Except, it turns out, this bold new paradigm was based on a lie. In 2018, a group of small advertisers sued the site, accusing it of massively overstating video’s reach. (In the site's defense, Facebook's lawyers claimed overstatements of just 60 to 80 percent; the plaintiffs claimed it was an eye-watering 150 to 900 percent.) Facebook kept this data to itself for over a year, but the social media giant ultimately admitted to “misreporting” reach of posts on Facebook pages, the amounts of referral traffic from Facebook to external websites, and the number of views videos received on the mobile site. Facebook settled the lawsuit for $40 million — while refusing to admit any actual wrongdoing.

But the damage was done. The news came too late for the various publishers who’d relied on Facebook’s stated metrics, either making huge cuts or eating shit—or both—when it turned out nobody actually watched the videos they had spent so much effort and capital in pivoting to produce. Indeed, the flood of videos had the opposite of its intended effect — even for Facebook. A Wall Street Journal investigation of Facebook’s internal documents found that people had begun leaving the site in 2017, for reasons the site’s engineers had trouble pinning down, until they ultimately concluded “that the prevalence of video and other professionally produced content, rather than organic posts from individuals, was likely part of the problem.”

Authenticity, in other words — contact with real people — turns out to have been the key all along: a golden goose slaughtered in the name of making something bigger, flashier, and ultimately costlier.

Contact with real people is also key to the appeal of a city. Cities aren’t defined only by the people who visit them: they function in part through the vast web of interactions their residents create. It’s those webs of relationships, commerce, and discourse that make people want to stay. (In online terms, we call that engagement.) Without them, blight sets in. The city falls into disrepair and decrepitude, as more and more of its essential functions rust into nothing.

The compelling thing about dying cities isn’t just their decline, however: it’s the sense of unearthly activity in the ruins. As the old social media sites constrict around us, their fraying reality—like the weed-choked promenades and overgrown buildings of a doom-haunted metropolis—is overrun by things uncanny, unalive, and inhuman.

What are these ghosts that stalk our declining digital cities? And who precisely let them in?

For all the wires, tubes and servers that make up its physical components, the internet’s infrastructure is, in a sense, magical: a vast, ramshackle network of semi-thinking entities, given shape, instructions and purpose by coded workings as arcane (and tricky) as any spell. Many online workings particularly rely on bots, software applications that run automated tasks as surely and brainlessly as any homunculus or lesser djinn.

These servitors — while a necessary part of digital cities’ infrastructure — are not, themselves, the city. Or, at least, they shouldn’t be. Yet the internet security firm Imperva, which purports to measure bot traffic online, reported in 2016, some 52% of internet traffic was driven by bots rather than humans. This year, that number’s down to 42%. But the company notes that malicious bots — malignant, unconscious things that sometimes pretend to be people — accounted for 27.7% of all global website traffic in 2021, a new record. Step out into the digital city and you appear to be surrounded by crowds — but at the moment, only a narrow majority of those apparent throngs are human; a significant chunk of the inhuman are actively malevolent.

The web is built on the notion that traffic—the size and movement of the city’s crowd—is a good model for engagement. Yet such assumptions have led to a disconnect between the size of the crowd and its makeup. What happens when the teeming populations of our digital cities are barely human? Who are they for? As early as 2013 — fully a decade ago — half of YouTube traffic was “bots masquerading as people,” spurring employee fears of “the inversion,” a coming threshold where the site’s automated systems for catching fake traffic would start considering bot traffic as real, and human traffic as fake.

Let’s talk a bit about those automated systems, which we call algorithms. These are the specifically programmed instructions that determine how programs work and what we see online. They take in information, these unthinking things, and spit out data. They, too, serve a necessary purpose in the internet’s infrastructure.

But the urge to set algorithms to greater and greater tasks — to the shaping of the space itself— has been too much for online rulers to resist. Increasingly, the corporate algorithm can hire you, and the algorithm can fire you. The dating algorithm can determine who you match with online. The crime algorithm can take all the thought out of who’s likely to be innocent, and who’s likely to be guilty. The machine-learning algorithms can chew up real people’s art and spit out something smooth and uncanny, unthinking as a ghost. The algorithm may not be able to directly determine what you think, but it can determine what you see, feeding you a steady drip of madness.

Algorithms are as dangerous in their own way as any djinn or demon. They do not work according to human logic, with its complicated blend of intuition, empathy, and reason. They move instead according to our hidden fault-lines, oversights and cruelties. Summon them through code and set them to a task, and they will give you precisely what you asked for, whether or not that’s what you wanted.

Crucially for our purposes, they also do not inherently distinguish between the human and the unalive. And in so doing, they make it easier for little inversions to occur.

Here’s an example of what that looks like. In November of 2018—the same year that Facebook was sued over its (to give it the most charitable read possible) ‘misrepresented’ advertising metrics—the Justice Department indicted eight people for swindling advertisers out of a combined $36 million. The scheme allegedly involved creating fake people to look at ads, and fake websites to host them.

Writing in New York Magazine later that year, Max Read laid out the scheme: The criminals infected 1.7 million computers with malware—malicious bots—that remotely steered traffic to spoofed websites, designed to trick advertisers into believing their ad was being seen on sites like Vogue or The Economist. The bot-possessed computers faked social network logins, clicks and mouse-movements. Algorithms read them and, in effect, signed off on them. The result? “Fake people with fake cookies and fake social-media accounts, fake-moving their fake cursors, fake-clicking on fake websites,” Read wrote. “The fraudsters had essentially created a simulacrum of the internet, where the only real things were the ads.”

But even the “real ads” are far less solid than you’d think. Digital advertising is absolutely foundational to the modern internet economy: global spending on it was $325 billion in 2019, and could hit $525 billion by 2024. It dictates the economies of sites like Facebook and Twitter — to say nothing of search giant Google and commercial titans like Amazon. Human connection and internet infrastructure was always the bait in the trap: the real business was selling advertisers “highly targeted” ads based on their close study of our demographics, interests and behavior.

The problem is that ads don’t actually work. The “targeted” ads are remarkably inaccurate. Humans people barely click on them, regardless of how much you spend; advertising fraud of the sort mentioned above is ubiquitous. Companies have canceled huge ad-buys—for which they spent more money than you or anyone you know will ever see—and nobody noticed.

And yet spending continues, in part, because humans are now barely involved in the advertising process at all. Where once an advertiser might strike a deal with a website to host a paid banner, Gilad Edelman wrote in Wired, now every click you make online is accompanied by hundreds of thousands of companies competing to show you their ad, in automated cascades of auctions that occur over the space of milliseconds, billions of times a day. Advertisers often don’t know where such ads will load, on what site. And as we’ve noted, a large chunk of the traffic those ads receive isn’t human.

It’s a digital real estate bubble rather like the one that crashed the American housing industry—and by extension, a large chunk of the global economy—in 2008, Edelman notes. And in order to keep it going, everybody involved has to keep whistling past the graveyard, chumming their ads out into a digital city, for an audience of unalive people, a vast and churning machine that generates money as long as nobody looks directly at it.

The creeping unreality of this demon-haunted landscape has not gone unnoticed. Some forum-goers now push the Empty Internet theory, which argues that the internet actually ended in 2017, and that it’s now “empty and devoid of people,” as well as “entirely sterile,” with its “supposedly human-produced content” generated via a mixture of AI and bot traffic. The masters of this dead internet, the theory’s originator claims, are a group of corporate-paid “influencers” working with the government to get us to buy stuff.

In some ways, this is materially wrong. There are still real people in our digital cities, joking, arguing, shitposting, sharing pictures of pets and children. Deciding otherwise is a highway to madness. (Are you a bot? Am I? What is real? Who is reading this?) Moreover, social media companies and advertisers have every incentive to try and get bot fraud under control, if only to keep the online attention economy from completely collapsing.

Yet as Kaitlyn Tiffany notes in The Atlantic, the Empty Internet Theory captures something essential about the strangely repetitive and fake nature of life on social media. (It is, in fact, less a theory than a myth: materially false and yet full of deep explanatory power.) “The big platforms do encourage their users to make the same conversations and arcs of feeling and cycles of outrage happen over and over, so much so that people may find themselves acting like bots," Tiffany writes.

And as such, humans — life conditioned to imitate unlife — are "responding on impulse in predictable ways to things that were created, in all likelihood, to elicit that very response.”

The inversion that Youtube’s engineers feared — the idea that bot traffic would be seen as real, and human activity as fake — has already happened, albeit in stranger and subtler ways than they anticipated. The city is no longer for people, and somehow that doesn’t matter. Algorithms trawl digital networks, competing to show advertisements to unseeing clouds of bots. Bots click ads and boosting follower counts. Made-up engagement numbers turn into made-up money, which itself turns—through some strange alchemical process—into “real” monetary value, for someone, somewhere. Maybe.

Leading one to grapple with the persistent and unanswerable question: Am I even necessary in this process? Who or what am I really talking to? What are we fucking doing here?

Thinking of the slow collapse of the centralized online ecosystem, I remember old Yaxha, lost and buried beneath the jungles of the Peten, and the folklore around lost cities and shunned places. As Annalee Newitz writes in their excellent book Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age, most such sites aren’t lost so much as abandoned. Places like the great Mississipian mound city of Cahokia and the monumental temple complexes of Angkor Wat attracted people at first. Then they were beset by political trials and strife, as well as slow, cascading failures of infrastructure or ecology. At first, issues got fixed. Eventually, they didn’t. And in the fullness of time, people got fed up and left.

What drives these cycles of centralization and dispersion? Newitz argues that the cities which last are those which draw people in—and keep them around—in a dynamic circuit through “resilient infrastructure, accessible public plazas, domestic spaces for everyone, social mobility, and leaders who treat workers with dignity." Support for such public features helps cities continue. Losing them leads to a lessening of a city’s gravitational pull, and people choosing to leave. Sometimes, a city is reborn, pulling people back in — the many iterations of Rome, Jerusalem, Alexandria, Mexico City. Other times — perhaps, like Babylon or Troy, after an unfathomably long life — it simply dies.

Decentralization isn’t inherently a bad thing, of course. For all the grandeur of the place, for all its attractions, people were generally healthier outside of Rome than in it, less prone to epidemics and ill-hygiene and the heavy hand of autocratic law. (Cities, as friend of the newsletter Patrick Wyman likes to say, have historically been net consumers of people.) In The Dawn of Everything, David Graeber and David Wengrow’s lively account of how states formed, the authors consistently reiterate that people throughout history have not been trapped on some march of progress, whereby centralization is the only possible destination. Instead, people have instead made choices about how and where they wanted to live. Throughout history, people have looked at cities or societies and decided that they look like far more trouble than they’re worth.

If Facebook, Twitter and YouTube are cities—online cities, dreamt cities, cities fashioned out of words and carried on the backs of unalive things—then it seems that many people are increasingly running the same calculus that drove past people to abandon concrete ones. Writing in Garbage Day, Brodrick suggests that an “unbundling” is coming, and that the centrifugal force of the major social media sites is failing, sending people spinning out into the new villages and outposts of the internet: places like Discord, Mastodon, Pillowfort, blogs, and (ahem) newsletters.

For some, this exodus is driven in part by the slow rot in digital infrastructure, and the increasing prevalence of the unalive, which is now spreading into the far-more-personal world of calls and texts: spam and porn-bots, mad and maddening algorithms. For others, specific decisions by the city’s lords — a ban on pornography on Tumblr, a refusal to ban fascists on Twitter — have sent them scurrying. Still more look at an incoming administration, like Musk’s Twitter purchase, and decide it’s time to go.

What remains when people leave? Dwindled settlements, ruins, lore and ghost stories. Some sites hold on to a handful of people, diminished but still active amid the remains of the past. Such places remain worth a careful visit, from time to time: there’s useful material to be had there. Others (like Facebook) are increasingly shunned, as former users fear who — or what — lurks inside them.

But most common are the places that have simply outlived their usefulness. Sometimes their bones still stand, built of frozen emotions and forgotten contexts, links and posts rotting like ceiling timbers in an old house. Sometimes you look up and they are simply — gone.

You’ll miss some aspects of them: the agora, the fountains, the ability to run across unusual and interesting people and learn unusual and interesting things. They were nice enough to have for a while. But not, in the end, necessary. The autocrat might sit on his throne in the far away city, issuing mad decrees amid the rubble and the spirits: let him. He cannot stop you from leaving if you want to. Heaven is high, and the emperor is very far away.

You've been reading Heat Death. We — or something that looks very much like us — will see you soon. If you'd like to support the newsletter or leave a comment, you can grab a paid membership for just 5$ a month. Or just keep enjoying our free offerings by signing up right here.

Member discussion