Decline And Fall: Phantom Menaces

Lights up. A spaceship streaks through the void toward the great form of a battleship, hovering over a seemingly idyllic world.

Inside, a pair of warrior-monks turned diplomats are prepared to try and defuse a crisis that never should have occurred: the private military blockade of a sovereign state.

Before this crisis has ended, one of those monks will be dead. The other will be responsible for the care of a young boy with a very important future. A senator from that lovely little planet will have ascended to a position of considerable power. A drone army will have been deployed in a lethal field test. And the tectonic processes driving the decline and fall of the Galactic Republic will have lurched fully into life…

Welcome to Decline and Fall, a Heat Death series about history, America, and Star Wars. As always, we’re Asher and Saul Elbein, your humble guides. Last time, we talked to historian Patrick Wyman about the processes of history in Star Wars. This time, we're going to ask a simple question with a somewhat complex answer: Where do we begin? How did we get to this place of collapse, a republic and an empire crumbling around us?

Which is to say: Did it start in 2000, when President George Bush had an election stolen for him by Republican operatives and a willing Supreme Court? In 1999, when President Bill Clinton was impeached by some of those same operatives? Or in 1995, when a racist, right-wing terrorist Timothy McVeigh set off a bomb in Oklahoma City, prompting the passage of an anti-terrorism law that ignored the homegrown threat in favor of laying legal groundwork for decades of war?

Star Wars is in many ways the Aeneid of American decline, an epic riff on the unraveling of societies — glacially slow and then horribly fast. In many ways, the historical circumstances around the birth of The Phantom Menace track the major motions of its plot as the curtain comes up: a period of apparent peace concealing, barely, the potential for horrific violence.

We have to start somewhere, so let’s start there. As reporter Spencer Ackerman writes in his book Reign of Terror, the McVeigh bombing presaged a series of events with which we have now all become drearily familiar.

A former infantryman who served in Desert Storm, McVeigh had strong connections to the Christian white supremacist movement, and he shared their grievances: a seething contempt for other races and the belief that secret cabals of Jews ran the U.S. government. The bomb he set killed 168 people, nineteen of them children — then the worst terrorist attack in American history, recalling the car bombings of the Lebanese Civil War.

This was, it is important to remember, before mass shootings and other forms of mass death had become such common features of the American news cycle. Many journalists and their law-enforcement sources immediately blamed Muslims. (“Shoot them now,” one tabloid writer wrote of foreign diplomats and students, “before they get us.”)

Eventually, of course, McVeigh was caught by an Oklahoma State Trooper — reportedly wearing, in an uninventable touch, a t-shirt with a picture of President Abraham Lincoln and the words Sic semper tyrannis. These, of course, being the words supposedly shouted by assassin John Wilkes Booth after he shot the president at the end of another period of American crisis.

With his capture, another set of wheels spun into motion: a press that treated him as simply a survivalist, a misguided patriot, whose racism had to be explained away in order to fully understand him. Political actors like talk show host Rush Limbaugh and Republican firebrand Newt Gingrich on the right howled furiously at the notion McVeigh represented any resemblance to — or outgrowth of — their own reactionary politics. A centrist government spoke platitudes against generic “hatred,” but stopped short of further enforcement. An anti-terror bill that was rapidly stripped of any provisions allowing for closer inspections of white supremacist violence, while increasing prosecutorial power to go after “foreign” sources of terror.

From this side of history — after countless car bombings of mosques and markets in Iraq following an American invasion; after countless concerts, classrooms and churches were torn apart by high-powered rifles in the hands of young men right here — these read as flickers against the night; explosions that in their flashes give light to a vast negative space looming over us, like, well, a phantom menace: a dark and violent tension struggling to emerge from a political system that struggles, itself, to do much of anything.

But from that side — on the front side of the door — it doesn’t look that way at all.

Just another little dustup in this great and stable republic of ours, in other words, albeit with a higher-than-usual body count attached to it. Or, if you like, a foreshock. A sign where things were heading.

But we’re here to talk about Star Wars, aren’t we? In 1994, as McVeigh began concocting his plan to attack the federal government, George Lucas started work on his grand return to Star Wars.

The franchise had spent well over sixteen years in the wilderness, kept aloft by a procession of licensed books, comics and video-games, as well as a wildly successful re-release on video. But this was, fundamentally, a niche market. Generally speaking, Star Wars had been away, with no real sign that new films were on the horizon. Now, Lucas conceived an ambitious new trilogy, built around the tragic fall of the heroic Anakin Skywalker into the masked villain Darth Vader.

We’ll talk about the earlier movies, which made his name, later on — we’re ordering this story by the chronology of the world Lucas and his colleagues invented, not the one which, you might say, invented him, or imbued his schlocky space movie with the power to make and unmake worlds.

For now, let’s just say that they were a big deal: an achievement that both made George Lucas and that must have hung about his neck like a collar, robbing him of the ability to be anything but the man who created Star Wars — the reluctant and resented king of an empire of fans who had grown up in the shadow of his movies, as well as his vision of American empire subverted by the spirit of revolutionary American freedom. And also, obviously, X-Wings and lightsabers.

The announcement that Star Wars was coming back and subsequent publicity push unlocked a tremendous groundswell of enthusiasm. (We can see here shades of the Joseph Campbell faux-mythic patterns Lucas loved: The king had been in exile, and now the king had returned.) According to Secrets Of The Force, an oral history of the Star Wars films, theater owners in 1998 found to their shock that showings for now-forgotten films like The Waterboy were selling out from people eager to catch a trailer for the first film in the trilogy: The Phantom Menace. Before that film’s release, die-hards were camping out in front of theaters. By the time it closed, it had grossed a little over a billion dollars — which, adjusted for inflation, puts it comfortably in the neighborhood of Disney’s 2018 mega-blockbuster Avengers: Infinity War.

(Disney, of course, now owns Star Wars as well, and it’s a curious note that in 2015, The Force Awakens, which we’ll cover later — and which also brought back Star Wars after a long period in the cultural wilderness — made almost exactly the same amount of money as Phantom Menace, again adjusted for inflation.)

The Phantom Menace also signaled something else: a self-conscious and reactionary turn in fandom that has continued, with gathering heat and venom, to this day — presaging and to some extent contributing a similar turn in the culture.

While plenty of people liked The Phantom Menace well enough at the time, including us here at Heat Death — it’s hard to hit a billion in sales, after all, on a project the majority of viewers hate — many adult fans who had grown up with the original Star Wars were not well pleased to return and find that Lucas had made an adventure serial for children with a light political seasoning and an (admittedly grating) comedy sidekick. (A formula, as cultural critic Chuck Klosterman has pointed out, that is disturbingly similar to the original Star Wars films.)

A critical mass of these, influenced by the tendencies toward group-think and reactionary polarization fostered by then-new internet fandom—decided that they hated it, and more than that, that it was the film that ruined Star Wars. A belief which became a kind of dogma, helping to drive Lucas himself into retirement and preparing the field for Disney’s later, 2015 pledge to Make Star Wars Great Again.

Watching the movie now, it’s easy to see why people were frustrated. The Phantom Menace is a genuinely odd film to hang the grand return of a franchise on, and an unusual way to kick off an epic trilogy about the rise and fall of dynasties against the backdrop of democratic collapse. Its stakes are seemingly low; its performances wooden; its intrigues appearing to go nowhere in particular. In the supervillain-and-exploding asteroid filled Hollywood cosmos of the 1990s — its principal bad guys are called the Trade Federation, for God’s sake. The ponderous mythos of the dark sorcerer Darth Vader may as well belong to another universe.

But give Lucas credit: he gets us there, and in many ways he gets the last laugh.

Seen from the distance of a generation — seeing how the story turned out — the movie seems to be much more significant and prescient than it seemed at the time: a genuinely odd cultural artifact, permeated with the energy of the time, that hangs like a bridge between the age of kooky 90s blockbusters and the brutal noir of the War on Terror. Taken on its own terms, then, The Phantom Menace is a useful beginning —not in spite of its oddness, but because of it. This, Lucas says, is where the story starts, and where ideas central to his narrative are introduced. Let’s take him at his word, and see what kind of story he’s now trying to tell.

Strange Doings In The Galactic Republic

“Turmoil has engulfed the Galactic Republic,” runs the opening crawl to The Phantom Menace. “The taxation of trade routes to outlying star systems is in dispute. Hoping to resolve the matter with a blockade of deadly battleships, the greedy Trade Federation has stopped all shipping to the small planet of Naboo. While the Congress of the Republic endlessly debates this alarming chain of events, the Supreme Chancellor has secretly dispatched two Jedi Knights, the guardians of peace and justice in the galaxy, to settle the conflict…”

And we’re off. The film begins at a point when the Galactic Republic—that grand, prelapsarian vision of civic unity, liberty and order that everybody in the Star Wars universe will subsequently strive toward or react against — is as close to peace as we’ll ever see it. There are no vast wars being waged, no superweapons under construction. By the standards of the Star Wars franchise, things are positively quiet.

Yet the first thing we’re told in the film — a point that will be hammered home for the next 136 minutes — is that all is not well. The Galactic Senate, which seems at first glance to be a supranational governing body akin to our own EU or United Nations, has become largely ineffectual. The processes of government are gummed up by bureaucratic maneuvering and procedural gridlock, endless debate and little action. Issues that require urgent attention are constantly getting bogged down in committees, and while there’s apparently a judicial system, their rulings only seem to come down after events have made those rulings moot.

Nature abhors a vacuum, we’re told, but politics abhors it more. With the Republic paralyzed, organizations like the Trade Federation — a kind of interstellar shipping and trade cartel — have begun seriously throwing their weight around, to the point of unilaterally blockading the lovely green Republic planet of Naboo, ostensibly as part of a trade dispute.

This is an unusually bold move for the Trade Federation, we are told — but not an unimaginable one. And it seems at first like the system is flexing, perhaps, but not breaking. The notion of business interests as their own powerful quasi-state force would have been close at hand in 1998, after agencies like the International Monetary Fund essentially blockaded “debtor” countries like Argentina.

Under the rules of the liberal order, this is acceptable. Directly killing people. however , is a no-no. Yet when our leads, the unorthodox Jedi master Qui-Gon Jinn (Liam Neeson, craggy) and his apprentice Obi-Wan Kenobi (Ewan McGregor, urbane) secretly arrive to try and smooth things over, their appearance provokes an unusual response. The Trade Federation leadership, acting under orders from a shadowy figure in a hologram, tries to assassinate them.

Then — again under their patron’s orders — they lay an interdict over all communications and begin a military invasion of Naboo, with the end goal a treaty legitimizing their occupation of the planet. (“Is that legal?” the leader of the Trade Federation wonders. “I will make it legal,” their shadowy patron growls right back — suggesting his possible connections in the center of the Republic’s government.)

With that, the crisis — and thus, the plot — is off and rolling. Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan make their way down to the planet, collecting froggy native Jar Jar Binks (Ahmed Best, innocent) and the brave, teenage queen of the Naboo, Padme Amidala (Natalie Portman, beatific) along with her retinue of identical handmaidens. After a certain amount of running and gunning, they blast their way off the now-occupied planet with the aim of making it to Coruscant, the core of galactic governance, to plead for government intervention.

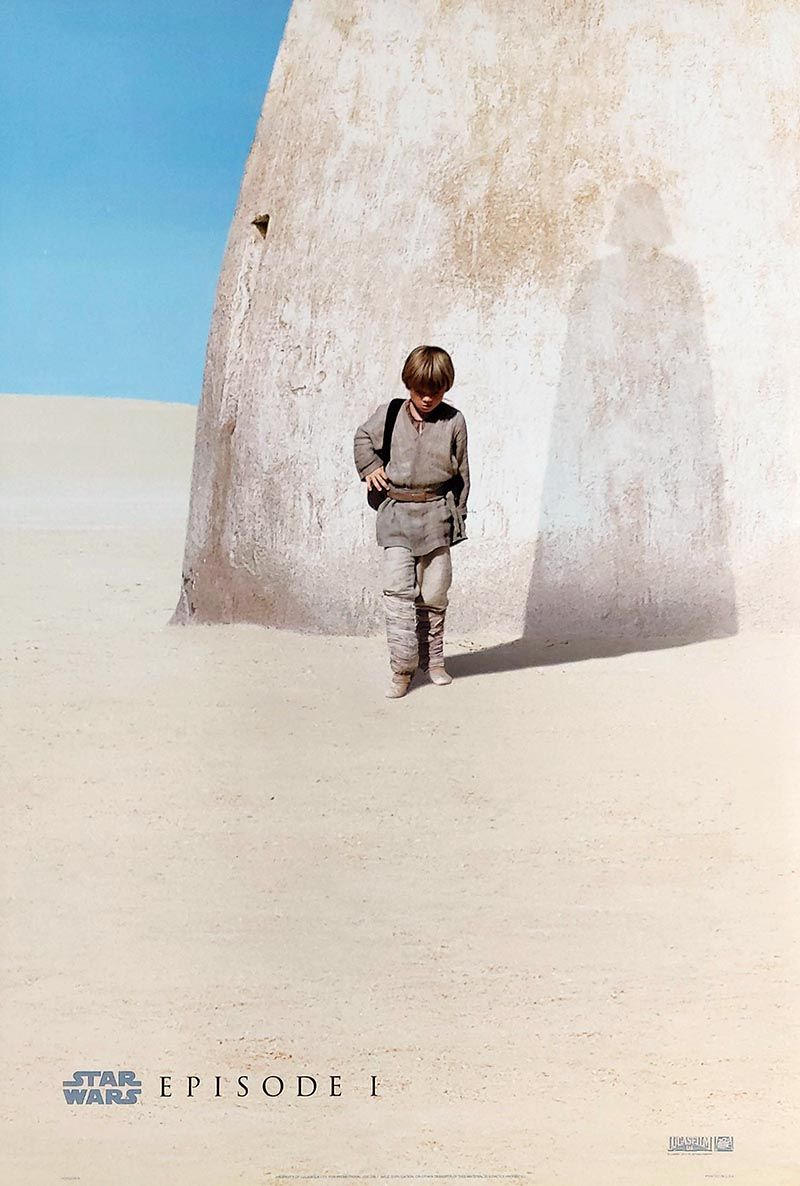

Their ship, however, was damaged in the escape. And so rather than heading directly to the center, our plucky heroes are forced to make an unscheduled trip in the opposite direction—to the wild periphery of the Republic — represented here by the barren, searing sands of Tatooine.

It’ll turn out to be a pretty momentous trip. In Star Wars, visits to the frontier always are.

Frontiers and Centers

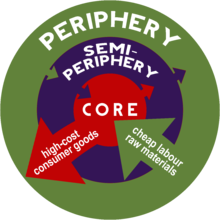

Let’s go ahead and introduce a lens that’ll prove useful to understanding the shifting tides of both Star Wars and America as a narrative project. We’re drawing here on world systems theory, an approach to imperial history that eschews looking solely at the doings of nation states in favor of considering them in a global context. (We talked about this with historian Patrick Wyman in the last installment of this series.)

Without going too deeply into the theory, hegemonic powers exist in a tension between the imperial core (the center of an empire) and the periphery (the source of raw materials and cheap labor.) Both poles exert their own gravitational pulls in relationship to each other: fine imperial goods and decrees going out, people and resources along the periphery being continually pulled in, and zones in between acting as places of interchange.

Peripheries often lie along the frontier, landscapes at the border of an empire, where aggressive war is waged when the empire is strong, but where the grip of the central state is otherwise relatively weak. With its shifting sands, desert climate and dusty sets, Tatooine recalls America’s own frontier throughout the 19th century: the imaginary lands we now call the Old West, a shifting zone of influence across the continent nebulously claimed by Washington, the site where Americans fought imperial wars against rival nations from the nomadic confederacies of the Comanche and Lakota to the settler republic of Mexico.

Many of the freewheeling, violent features of that frontier might have been familiar to, say, a Goth near a Roman garrison town in the 5th Century, or a 13th Century Mongol in the shadow of China’s Great Wall — a zone where destruction and opportunity were two sides of the same coin. A coin, to stretch the analogy a bit further, which was spent for mercenary service and raw materials and paid for the pleasures of civilization, bought cheap in the imperial center and now sold dear.

The frontier can be thought of, a bit fancifully, of as a perpetual zone in the human, or pre-human, imaginary; a place our species moved constantly toward on our way out of Africa, as it receded beyond the horizon. A place where new dangers and new opportunities arose, and also where cultures— human, plant, animal, bacterial and viral — met and melded.

In imperial terms, the frontier is like the permeable membrane at the edge of a great cell: an entry point for a continual stream of resources and labor, and a periphery for the restless, criminal, or ambitious to escape to — and a place where, from time to time, new ideas emerge to reconquer the center. As cracks between continents burp out the lava that makes the land, so too does the frontier push out culture.

While that dynamic isn’t unique to any time or place — it can hold as well for maritime frontiers as terrestrial — in America, that entire dynamic is indelibly wound up with a specific time and, above all, a specific landscape. As a result of the relatively late conquest by Europeans of this portion of the continent, the idea of a frontier and the many varied forms of the dryland continental ecosystem—whether that’s open prairie or desert—are inextricably linked in the American mind. The desert/frontier is a hard land but an individualist paradise; the desert/frontier is where you go to vanish; the desert/frontier is where legends are born.

Here, then, is Tatooine: Star Wars’ prototypical desert planet, source of two of the franchise’s most important characters, and the most consistently visited (and iterated upon) location in the films. The film labels it as in the “Outer Rim territories,” language that necessarily evokes the American West; Qui-Gon describes its society as “moisture farmers for the most part, some indigenous tribes and scavengers...the spaceports are havens for those who don’t wish to be found.”

When our heroes land on the outskirts of Tatooine’s Mos Espa settlement, their goal is to pick up the necessary supplies to get them off the planet as soon as possible. Threading their way through the bustling markets—full of every imaginable sort of alien, busted droids, and strange pack animals—Qui-Gon and Amidala find at every turn that Tatooine’s relationship with the Republic is essentially nonexistent. The Republic may reign, but the planet is ruled by powerful gangster clans, who legitimize their power by performing important civic functions (overseeing wildly dangerous sports like pod-racing, much as East Roman emperors presided over chariot races) and settling disputes. When the two try and buy spare parts off of junk dealer Watto, he dismisses their attempt to pay in Republic money, demanding something “more real.” Qui-Gon’s Jedi mind tricks—one of the primary ways that Jedi seem to finesse their way through difficult situations—don’t work on him, either.

A flying, tapir-snouted little wheeler-dealer, Watto is important in two particular ways. First, he’s the primary non-human character we meet on Tatooine, and in a sense, he is Tatooine in this first film: outside the grasp of Republic law, economics, social customs, or even mind control. More crucially, it’s in his junk shop that we meet the boy who will grow up to deliver the coup de grace to the Galactic Republic.

The boy’s name is Anakin Skywalker (Jake Lloyd, adorable but not much else), a last name that would resonate with any viewer who had camped outside a 1998 megaplex like a struck chord, directly to the hindbrain. Skywalker. To Qui-Gon and Amidala, though, he’s just a good kid— friendly and generous, a whizz with machines. We’ll soon learn that he’s more even than that: a person of extraordinary magical potential, whose life will end up being a nasty indictment of every system—the Jedi, the Republic, the Empire—that he directly interacts with.

That starts very early, with the fact that he was born into slavery. Slavery, a horrified Amidala points out, is illegal under Republic law — at least, when slavery is inflicted on organic beings. (As we’ll see, the whole Republic is built on the socially-acceptable enslavement of sentient machines.) Thus, when Anakin meets Qui-Gon, he quite naturally assumes that the powerful Jedi Knight has come to overthrow the system that keeps him and his mother imprisoned.

Qui-Gon is, of course, there for no such reason—the petty systemic evils on the Republic frontier are not at the top of his priority list, given the Serious Political Crisis he’s been tasked with solving. But he recognizes real power in the kid, gambles with Watto for him, and helps win his freedom. That freedom, however, comes with a price: his leaving the only home and family he’s ever known — his mother is left behind — in order to join an ossified, sclerotic order of warrior monks. (Who, it transpires, aren’t that pleased to have him.)

But to make that disappointing discovery, however, our characters have to blast out of the frontier and into the very center of galactic politics: the urban planet of Coruscant. For Anakin and Amidala, it’s an overwhelming sight: a planet covered in towering skyscrapers, lines of shimmering, flying cars stretched in three-dimensional traffic jams, monumental buildings of staggering, unimaginable size.

It’s exactly what you’d expect the self-styled core of the known universe to look like, in fact: no fields, no farms, no forests, just towers and traffic and hustle and bustle, the final destination for resources and trade, a great greedy mouth swallowing up everything the periphery can provide and shitting out trash as its towers grow higher and higher; a glittering planet-scale New York or Shanghai by way of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.

This is also where, for a lot of fans, The Phantom Menace suddenly slams into a wall. There’s a sudden tonal shift, as the movie judders unevenly from capering space opera to that other mode that so annoys people about the Star Wars prequel trilogy: a staid, high-costumed political drama. (That, after all, is what often happens in imperial centers: Very Important People intriguing against one another and not doing, it seems, very much.)

Upon their arrival, Qui-Gon and plucky Queen Amidala both receive somewhat nasty shocks. For the Jedi Master, it’s that the council isn’t greatly interested in backing him in training Anakin Skywalker as a Jedi. For Amidala, it’s the revelation that the gridlocked Senate cannot—or more properly, will not—act to end the unprecedented private occupation of her home planet and bring the Trade Federation to heel.

She is guided to this realization, of course, by the kindly, avuncular senator from Naboo: Palpatine (Ian McDermid, oleaginous). Under his suggestion, Amidala instigates a parliamentary coup, undercutting the paralyzed regime that had dispatched the Jedi to her aid, and giving Palpatine an opening to get himself voted into the executive seat, setting him on the path to consolidating power.

Because while the film never directly reveals it, Palpatine is, of course, the titular phantom menace, the orchestrator of the crisis, and a man intent on reshaping the ailing Republic in his own dark image.

Let Us Beware Great Men

Fantasy fiction — which is generally the genre Star Wars belongs to—tends to move according to the theory that Great Men (and it is unfortunately, in most of these epics, men) shape history, generally by enforcing their will upon it. By this point, The Phantom Menace has established that the Republic is rotten, but it also has gone out of its way to position Senator Palpatine as central to that sickness, and in some ways the prime mover in it.

So let’s talk, then, about Palpatine. In Secrets of the Force, the oral history about the making of Star Wars, Lucas calls Palpatine “the devil,” which is to say, a tempter and corruptor. Fair enough. Palpatine is introduced as the mastermind of the Naboo crisis, appearing as a snarling, hooded hologram. (That is to say, an insubstantial body. A phantom.) This flickering example of caped foreshadowing is Palpatine in his aspect as a secret commander of the Sith — an outlawed faction of magic users, hiding themselves from the Jedi Order and plotting a nebulous, eternal revenge.

The precise details of who and what the Sith are genuinely doesn’t matter, regardless of how much ancillary material digs into it: the important point The Phantom Menace establishes is that the Jedi Order believe the Sith to be their eternal enemies, forces of entropy and erosion, destruction and death. They are basically correct about this. They also believe that they've long since consigned the Sith to the dustbin of history. In this, they're dead wrong — and thus are missing the reactionary enemy scheming under their noses.

But though Palpatine is the senior in the Sith secret society — his nom de guerre is Sidious, as in “in-sidious” — most of his screen time comes in his daytime role as Naboo’s senator. (Here he’s also introduced, initially, as a hologram, whose words are vague and garbled, before appearing physically later in the movie. Star Wars, as we’ll see, loves to tease us with an image first displayed, diegetically, on screen.)

As senator, he’s a smiling, friendly cipher. Whether striding through plushily-carpeted halls of the Galactic Senate, or sitting in his hovering debating box in the great debating floor of worlds, he’s forever pulling Amidala aside and whispering about how bad things have gotten in the political center. He may not be an entirely trustworthy source, and is certainly partially responsible for the current crisis, but it’s often the case that fascists — as recently seen by Putin’s fulminations against NATO — have a fairly clear-eyed view about the weaknesses of the system they’re attempting to infect.

And yet seeing him as the Devil is unsatisfying — it takes the Jedi a bit too much at their word, given what we’re learning about the flaws in their order. So let’s turn our attention to Naboo, his planet of origin and the central flashpoint of this entire manufactured crisis. What sort of place could produce a man like Palpatine?

Naboo is, at first glance, an idyll. It’s verdant and lovely, a mixture of rolling fields and misty rainforests. (This sets it immediately against the barren frontier of Tatooine, or the megalopolis of Coruscant). Its cities are clean, a mixture of art-deco and classical marble, full of waterfalls and sleekly designed metallic ships. Its society is run as a vaguely elective monarchy, with its young queen, Amidala, decked out in ostentatious ceremonial attire. It’s a courtly, peaceful place, not quite at the center of things, but certainly not the frontier, either.

But let’s look a little bit closer. Somewhat unusually for Star Wars, and in stark contrast to both its diverse frontier (Tatooine) and cosmopolitan center (Coruscant), Naboo’s society — at least the part with a voice in Republic affairs — is largely made up of humans. The planet’s indigenous species, the Gungans—represented by the much-maligned, rabbit-eared, frog-skinned Jar Jar Binks—live apart, in hidden underwater cities, and have absolutely no presence in surface society, and no apparent voice in its politics. Prior to the events of the film, Queen Amidala, the ostensible ruler of the planet, has seemingly never met one. And while the film presents Gungans as essentially isolationist, viewed through the lens of our own history, it’s hard not to assume that their secrecy, mistrust and disdain for human society on Naboo is well earned.

Is it overstating things to call Naboo an apartheid or settler colonialist society? Maybe — though the humans presumably are the newcomers. But it’s certainly not in any sense integrated, and one wonders whether massacre sites lie beneath the opulent marble public buildings; if the Gungans live underwater because they prefer to, or because they were pushed there. It’s certainly not ridiculous to suggest that such a thing might have influenced a man like Palpatine — whose imperial structure will later be shown to be entirely dominated by humans.

The racial undertones here are a bit ironic, considering the film’s most lasting and widely-discussed problem: the fact that its primary aliens — i.e, Jar Jar Binks, Watto, and the Trade Federation — easily read as ugly racial caricatures. In interviews, Lucas flatly denies that this is intentional. But it doesn’t really need to be. The pulp serials that Lucas drew for Star Wars relied heavily on the trope of the Foreign Other—the “alien,” if you will—as an antagonist or comic relief, in ways that sprang directly from the racial assumptions of the white American imagination. Flash Gordon’s Ming the Merciless, Palpatine’s direct narrative forebear, is an alien in multiple senses of the word: of a different planet, of a different assumed race: a Yellow Peril caricature for the good and true American quarterback to fight. (Simply replicating that model is how you end up with something like The Trade Federation: cowardly schemers, played by white actors who speak in Japanese accents and wear squint-eyed prosthetics.)

But Palpatine, notably, is not an alien in any sense of the word. He is, if anything, familiar: an older white man, apparently perfectly average, a political operative from a minor world. Whether this is a deliberate or accidental point by Lucas doesn’t matter much. In The Phantom Menace, the actual threat comes from inside. It comes from a prosperous but not particularly wealthy planet, a place of unspoken inter-species tension, whose courtliness rings a little hollow, with the sort of political culture that could give one of its native sons a boost into the big time.

The suburbs, if you want to be glib. (A place like Kentucky, if you want to be even glibber.) These are not the only sorts of places that can breed ambitious, amoral strivers prepared to wreck things in pursuit of power. But in America, at least, they have a good track record of doing so.

For all the time we spend with Qui-Gon and Amidala, then, the two important figures to Star Wars’ broader story are Palpatine and Anakin: two figures from varying points on the periphery, who have come into the center—and whose arrival, with hindsight, marks the beginning of the end.

The Tools of War

But there’s business to take care of first. Amidala, her Jedi companions, and Anakin head back to Naboo in order to attempt to overthrow the Trade Federation by themselves, through a complicated plan that involves recruiting the Gungans to their rebellion’s aid.

This is a bit bumpy: Qui-Gon’s speech that two societies are symbiotically and spiritually connected understandably cuts little ice with the frog-like Gungan leadership, given that the planet’s human society has clearly been happy enough ignoring them. But — in customary adventure serial fashion — Queen Amidala effects a relatively easy reconciliation by prostrating herself before them and begging their help. From there, the Gungans agree to march out in force against Trade Federation occupation.

There’s a lot of incident that follows, very little of which particularly matters. There’s a reveal that Amidala has been secretly posing as her own handmaiden, a bit of narrative trickery that doesn’t actually amount to much and is simpler to just ignore. Over the course of the final battle, Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan end up in a duel with Palpatine’s apprentice, a largely silent, nonhuman lieutenant who manages to kill the older Jedi before being hacked apart by the younger. (This, of course, leaves Anakin without his patron and father figure, and Obi-Wan’s vow to honor his dead master’s wishes by taking the kid on as an apprentice is a responsibility the younger man clearly isn’t prepared for.)

But let’s return to the nature of the army that everybody is setting out to go fight, which is one of the more chilling aspects of Lucas' vision, in hindsight: automated battle droids. These arrive as infantry, unloaded in assembly lines from mechanized troop carriers, an entire army controlled by a single Trade Federation battleship tucked safely in orbit. That battleship is the crux of things: knock it and its operators out, and the pre-packaged army turns off, leaving the Trade Federation empty-handed.

Narratively, that ship exists so that little Anakin will have something important to contribute to the film’s plot, aside from the mere fact of his introduction into the larger saga. And of course he does—more by accident than anything—succeed in blowing it up, right at the moment when everything seems most dire. By that point, the droid army has successfully captured Queen Amidala, and routed the Gungan army with heavy casualties, and their sudden deactivation is the only thing that saves the day.

It’s interesting to note that pre-packaged droid armies are a defining feature of the prequel trilogy, and entirely absent from subsequent ones. For all that Lucas wrings a few comedic bumbles out of their apparent stupidity, the film continually returns to them as a genuinely threatening force: soldiers unfolding themselves from boxes, commanded from afar, marching cold and unfeeling upon the heavenly green pastures of Naboo. Not the sort of thing you’d expect a well-run Republican government to allow in private hands.

Yet the Trade Federation’s droid army is described as “battle-hardened,” an unnerving thing for a trading company’s security force to be. It suggests the questions: What battles have they been fighting, and against who? For all that the droid invasion is an escalation, the tools to carry it out have clearly been lying around for a while.

But then, consider the droids themselves. Though the word “robot” is seldom actually used in the franchise, its origin is instructive: it was coined in the 1920s, from the Czech robota, meaning ‘forced laborer’ or “slave,” as part of a literary protest against the horrors that industrialization wrought upon the working class. (Interestingly, the Phantom Menace draws as much from the art-deco movement of the 1920s for its ships and architecture as anything else, which is perhaps why Coruscant so directly resembles Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.)

Robots have generally carried that poetic suggestion of the underclass ever since. This, rather inevitably, has led to the general narrative thread of “robot uprisings,” coded in postmodern America as “Skynet.” After all, uprisings are precisely the sort of thing you’d fear a servile underclass might be plotting.

But Star Wars under Lucas — which is to say, for most of its history — completely eschews any such story. The films are largely interested in them as a kind of world-building texture: extras, comic relief, pets. Or, as here, as a directed military threat: the embodiment of a ready-made, unthinking, and directed army, without the capacity for pity. Of course, that’s the sort of enemy you don’t have to pity, either: the sort you can chop up with a lightsaber without it feeling too gruesome. It’s not like they’re people, after all.

But aren’t they? The Phantom Menace also introduces the franchises’ two most famous droid characters: R2-D2 (the little chirping astromech droid, in service to Naboo's aristocracy) and C-3PO (the prissy protocol droid Anakin has assembled from scraps in the desert.) Admittedly, neither plays much of a role here: R2D2 gets his first tour of duty flying co-pilot for a Skywalker, and C-3PO is a glorified cameo. But going forward, they'll occupy the role that comic servants might in a Shakespeare play, or that of the farmers in Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress: lower class rustics and bumblers, who comment on the action and occasionally manage to save the day themselves.

That role only works if R2-D2 and C-3PO are sentient enough to be characters in their own right. And they are: they bicker and react to things, keep secrets, lie, and are called brave. For that matter, the battle droids are characters as well: a bit dim, admittedly, but they do talk and address each other, a choice that’s intended to be comedic but undercuts Lucas’ usage of them as unfeeling. This fact doesn’t seem to particularly bother anybody. For all that Republic characters shake their heads and cluck about organic slavery, in fact, nobody — not even Anakin Skywalker! — will ever raises the obvious point: that the Republic is a slave society, too, one that runs wholly on disposable servants, soldiers, mechanics. And unlike the vast majority of American science fiction containing artificial intelligence, it’s something Star Wars resolutely refuses to engage with.

Of course, a society’s refusal to engage with uncomfortable implications is the lingering takeaway of the film. The Phantom Menace concludes with the droid army is defeated, the Trade Federation humiliated, and everything concludes with a joint street parade down the promenades of Naboo’s capital, with Amidala re-enthroned and formally recognizing the Gungans as allies. We also get a very smug Senator Palpatine revealing that he’s been elected the new Supreme Chancellor of the Republic—and casting a appraising eye over the promising frontier kid who fired the lucky shot. (In a clever musical touch, the score for the parade is a triumphal, airy rendition of the Emperor’s theme from later movies.)

In fact, the last word of the film, bellowed by the Gungan leader, is pointedly ironic, given all that’s coming: “peace.” The word is a period, putting a close to the whole nasty business. The Naboo crisis is over, everybody. Nothing more to worry about. Let’s all return to our previous norms, and just hope it doesn’t happen again.

The Looming Crackup

But the entire point of The Phantom Menace, of course, is that it will: that the prelapsarian world is riven by cracks, just waiting to be prized apart. In 1999, when the film came out, the American empire stood at the apogee of its international power and economic strength, with an unchallengeable military and a prosperous consumer society, a center drawing all things into itself, to the point where some American pundits felt comfortable forecasting an end to the whole business of history.

And yet that society was rocked by the first ugly outbreaks of mass killings. Not only the McVeigh bombing, either: a month before The Phantom Menace was released, two teenagers walked into Columbine high school and murdered 13 people, with the goal of exceeding McVeigh’s death count. This massacre, like McVeighs, was a simple thing rapidly obfuscated as complex: it was rapidly metabolized by the American political press, spun out into moral panics about youth subculture — rap music and Marilyn Manson, violent video games — and calls for higher school security and “zero-tolerance” laws, shoveling yet more children into the hungry, inescapable maw of the legal system.

But even these flare ups, so grim in light of future events, now seem like little flickers of lightning that underscore the size of the looming thunderhead. American society was sicker than anybody wanted to admit, hollowed out by the churning engines of “Reaganomics,” a nice word for a merciless process of financialization, outsourcing, and austerity. The country’s apparent economic growth was fed by continual privatization of the public sphere — an expansion into the frontier within.

Cracks everywhere, in other words, just waiting for the wedge and the hammer blow. The most famous of those would come in 2001, of course, with the Al-Qaeda terrorist attack on the World Trade Center, the epochal event that kicks off the “War on Terror,” which would be refracted in Star Wars in the mechanism of the Clone Wars.

But the other, rarely noted epochal change happened even sooner: the theft of the presidential seat due to the “Brooks Brothers riot” (of which people like several of our current supreme court, like recently appointed justice Amy Coney Barrett participated, and the then-supreme court — including current justice Clarence Thomas — allowed). Norms prevailed, in that a flagrantly illegal thing was allowed to pass in the name of civic unity. Peace, over justice.

What that showed the people responsible wasn’t that it wouldn’t happen again, of course. It made it clear that they had a potent weapon in their hands. It showed that they could get away with it.

Star Wars didn’t predict this, and Lucas is not a prophet — at least, not precisely. But the saga he created has always mirrored America in fractured ways, some intentional, others bubbling up from the culture he was creating in. He begins the chronological Star Wars saga by asking how a seemingly minor little dustup over taxation presaged the decline. Which is another way of saying: how everything went wrong.

That’s our story, too, as it happens. Sometimes, Star Wars seems out of touch. But it’s nearly always ahead of the curve.

This has been Decline and Fall, a Heat Death series on Star Wars and America. We'll be back in March, when we're headed into 2002 and the spin-up into the War on Terror. Till then, may the Force be with you.

Member discussion