Decline and Fall Free: Let Us Beware Great Men

Hey, folks! Over the past several months on Heat Death, we've been cooking up a special project: a series that discusses the decline of American empire through the lens of Star Wars, our foremost national epic. We've discussed the long arc of the Star Wars Saga. We've talked about drone warfare. And we've batted some of the broader themes around with historian Patrick Wyman.

Now, however, it's time to get cracking. Today, our feature length, 6,000 word rundown of the The Phantom Menace is available for paid subscribers. Rather than litigating the film's quality or plotting — exceedingly well-trodden ground, and frankly not that interesting — we instead put the film in its historical context, perform a close reading of the society it depicts, and try to get to grips with the political story that Lucas is trying to tell.

Here's a free excerpt, which discusses the character of Senator Palpatine, and considers the planet he came from.

Let Us Beware Great Men

Fantasy fiction—which is generally the genre Star Wars belongs to—tends to move according to the theory that Great Men shape history, generally by enforcing their will upon it. By this point, The Phantom Menace has established that the Republic is rotten, but it also has gone out of its way to position Senator Palpatine as central to that sickness, and in some ways the prime mover in it.

Let’s talk, then, about Palpatine. In Secrets of the Force, the oral history about the making of Star Wars, Lucas calls Palpatine “the Devil,” which is to say, a tempter and corruptor. Fair enough. Palpatine is introduced as the mastermind of the Naboo crisis, appearing as a snarling, hooded hologram. (That is to say, an insubstantial body. A phantom.) This flickering example of caped foreshadowing is Palpatine in his aspect as a secret commander of the Sith — an outlawed faction of magic users, hiding themselves from the Jedi Order and plotting a nebulous, eternal revenge.

The precise details of who and what the Sith are genuinely doesn’t matter, regardless of how much ancillary material digs into it: the important point The Phantom Menace establishes is that the Jedi Order believe the Sith to be their eternal enemies, forces of entropy and erosion, destruction and death. They are basically correct about this. They also believe that they've long since consigned the Sith to the dustbin of history. In this, they're dead wrong — and thus are missing the reactionary enemy scheming under their noses.

But though Palpatine is the senior in the Sith secret society — his nom de guerre is Sidious, as in “in-sidious” — most of his screen time comes in his daytime role as Naboo’s senator. (Here he’s also introduced, initially, as a hologram, whose words are vague and garbled, before appearing physically later in the movie. Star Wars, as we’ll see, loves to tease us with an image first displayed, diegetically, on screen.)

As senator, Palpatine a smiling, friendly cipher. Whether striding through plushly-carpeted halls of the Galactic Senate, or sitting in his hovering debating box in the great debating floor of worlds, he’s forever pulling Amidala aside and whispering about how bad things have gotten in the political center. He may not be an entirely trustworthy source, and is certainly partially responsible for the current crisis, but it’s often the case that fascists — as recently seen by Putin’s fulminations against NATO — have a fairly clear-eyed view about the weaknesses of the system they’re attempting to infect.

And yet seeing him as the Devil is unsatisfying — it takes the Jedi a bit too much at their word, given what we’re learning about the flaws in their order. So let’s turn our attention to Naboo, his planet of origin and the central flashpoint of this entire manufactured crisis. What sort of place could produce a man like Palpatine?

Naboo is, at first glance, an idyll. It’s verdant, lovely, and very green—a mixture of rolling fields and misty rainforests. (This sets it immediately against the barren frontier of Tatooine, or the megalopolis of Coruscant). Its cities are clean, a mixture of art-deco and classical marble, full of waterfalls and sleekly designed metallic ships. Its society is run as a vaguely elective monarchy, with its young queen, Amidala, decked out in ostentatious ceremonial attire. It’s a courtly, peaceful place, not quite at the center of things, but certainly not the frontier, either.

But let’s look a little bit closer. Somewhat unusually for Star Wars, and in stark contrast to both its diverse frontier (Tatooine) and cosmopolitan center (Coruscant), Naboo’s society — at least the part with a voice in Republic affairs — is largely made up of humans. The planet’s indigenous species, the Gungans—represented by the much-maligned, rabbit-eared, frog-skinned Jar Jar Binks—live apart, in hidden underwater cities, and have absolutely no presence in surface society, and no apparent voice in its politics. Prior to the events of the film, Queen Amidala, the ostensible ruler of the planet, has seemingly never met one. And while the film presents Gungans as essentially isolationist, viewed through the lens of our own history, it’s hard not to assume that their secrecy, mistrust and disdain for human society on Naboo is well earned.

Is it overstating things to call Naboo an apartheid or settler colonialist society? Maybe — though the humans presumably are the newcomers. But it’s certainly not in any sense integrated, and one wonders whether massacre sites lie beneath the opulent marble public buildings; if the Gungans live underwater because they prefer to, or because they were pushed there. It’s certainly not ridiculous to suggest that such a thing might have influenced a man like Palpatine—whose imperial structure will later be shown to be entirely dominated by humans.

The racial undertones here are a bit ironic, considering the film’s most lasting and widely-discussed problem: the fact that its primary aliens—i.e, Jar Jar Binks, Watto, and the Trade Federation—easily read as ugly racial caricatures. In interviews, Lucas flatly denies that this is intentional. But it doesn’t really need to be. The pulp serials that Lucas drew for Star Wars relied heavily on the trope of the Foreign Other—the “alien,” if you will—as an antagonist or comic relief, in ways that sprang directly from the racial assumptions of the white American imagination. Flash Gordon’s Ming the Merciless, Palpatine’s direct narrative forebear, embodies this: a Yellow Peril caricature from a different planet for the good and true American quarterback to fight. (Simply replicating that model is how you end up with something like The Trade Federation: cowardly schemers, played by white actors who speak in Japanese accents and wear squint-eyed prosthetics.)

But Palpatine, notably, is not an alien in any sense of the word. He is, if anything familiar: an older white man, apparently perfectly average, a political operative from a minor world. Whether this is a deliberate or accidental point by Lucas doesn’t matter much. In The Phantom Menace, the actual threat comes from inside. It comes from a prosperous but not particularly wealthy planet, a place of unspoken inter-species tension, whose courtliness rings a little hollow, with the sort of political culture that could give one of its native sons a boost into the big time.

The suburbs, if you want to be glib. (A place like Kentucky, if you want to be even glibber.) These are not the only sorts of places that can breed ambitious, amoral strivers prepared to wreck things in pursuit of power. But in America, at least, they have a good track record of doing so.

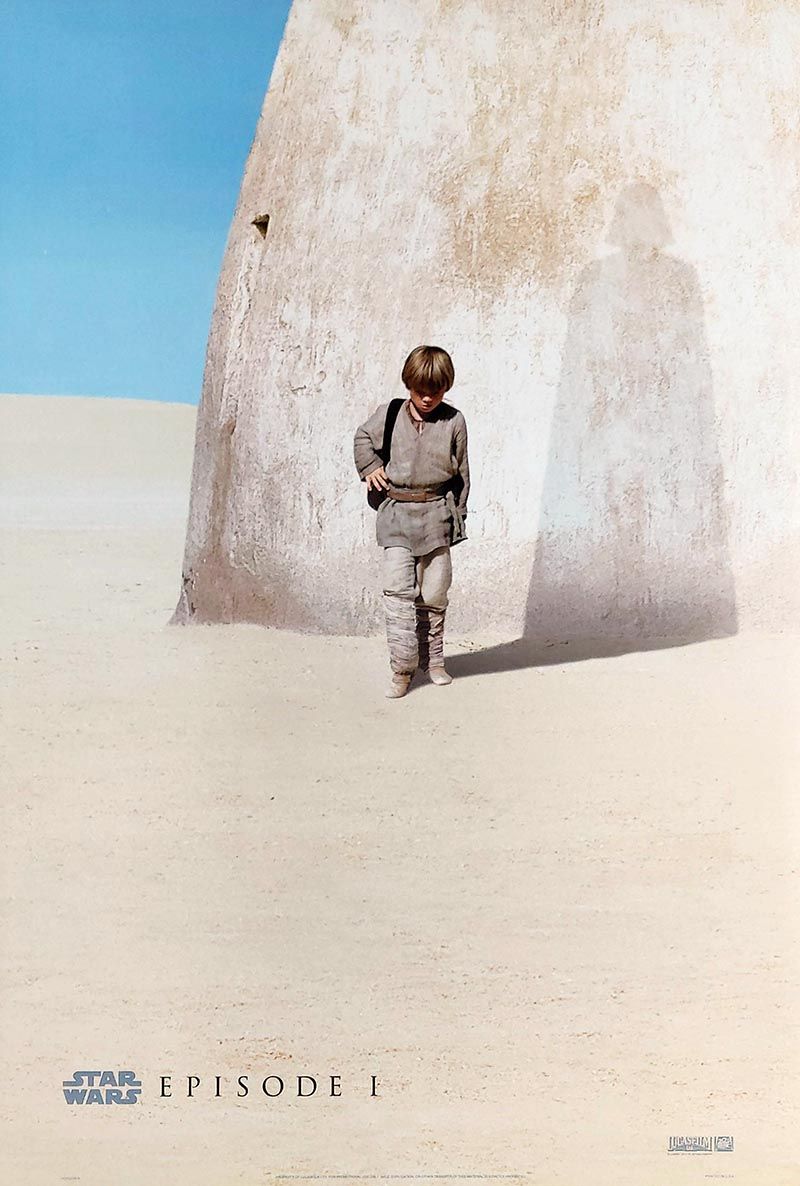

For all the time we spend with Qui-Gon and Amidala, then, the two important figures to Star Wars’ broader story are Palpatine and Anakin: two figures from varying points on the periphery, who have come into the center—and whose arrival, with hindsight, marks the beginning of the end.

To read the rest of the feature, you can upgrade to a paid subscription for just $5 a month, which will give you access to all paywalled material, as well as the ability to leave comments on articles. See you there!

Member discussion