Everything's Riverdale

Somewhere in America—probably upstate New York, but let’s keep it vague—there is a little town called Riverdale. It cannot be found on any map, but doors to it exist all over the country: in comics shops, grocery store checkout shelves, streaming television and out-of-context panels passed around on social media. Not precisely suburban, not exactly a small town, in no way a city, Riverdale exists as the narrative home-territory of Archie Comics, one of the longest continuously-published American comics of all time.

Archie (ginger, gap-toothed, girl-crazy) and his friends Betty (blond, tomboyish, Archie-crazy) and Jughead (whoopy-capped, wise, burger-crazy) debuted in 1941, in the pages of Pep Comics #22. Veronica (brunette, rich, confident) came along just a year later to complete the set. 1942 set the seemingly eternal dynamic in motion. Archie is eternally torn between Betty and Veronica, both of whom compete with one another to win the dubious honor of dating America’s Typical Teen.

Around and around and around they’ve gone, for almost 80 years, across a sprawling network of spinoff comics, digests, radio, videogames, movies and television shows, including the discount-David Lynch show Riverdale. It’s a simple setup and they are simple characters, by and large. But after 80 years and innumerable creative hands, even simple things tend to acquire weight and mass and idiosyncrasies of their own.

Archie Comics is like a koan. One must peer past the simple surface to glimpse the more occluded depths. One must be initiated into the deeper mysteries. Drink deep and descend. In the words of comics critic Richard Jones: everything’s Riverdale.

There’s a whole world between the city and between the farm, a world of margins inhabited by wilderness, liminality, and—alas—hormonal adolescents. (They’re like ants, these kids: they get everywhere.) Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that’s your teenage dream tonight.

Early June finds the Brothers Elbein back in their places and buckling down for the long summer ahead. Asher is in work mode, finishing up edits to a book project and juggling multiple pieces around the conservation of threatened Texas organisms. The first of those projects — a piece for Texas Monthly on the saga of the Red Wolf — came out yesterday, and came out rather well. Here’s an excerpt:

Part of the problem was that scientists couldn’t agree on the red wolf’s nature: was the animal a coyote-wolf hybrid, or a distinct species? If the former, anti-wolf activists argued, then it didn’t merit any protection under the Endangered Species Act. The idea of distinct species is scientifically a bit of a red herring: many populations described as separate species often happily interbreed along the frontiers of their range. As red wolves were hunted into near-extinction, remnant wolves mated with the coyotes moving into their former territory, giving rise to handsome hybrid populations like the one found on Galveston Island in 2008. Despite their wolf “ghost genetics,” hybrids receive no official protection; red wolf conservation efforts remain focused on animals that are genetically distinct from coyotes. For those canids, a 2019 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine came down heavily in the distinct species column.

Saul, meanwhile, is settling in to his first week at his new job: the Hill’s new sustainability newsletter, Equilibrium. (The newsletter launches officially on 6/21; it’s an exciting chance to try and bring environment and ecology content to the sorts of people who never would have thought they wanted it.) After being a lifelong freelancer, it’s also his first time holding down a desk job. To his surprise, he finds that there appears to be a time, at the end of most working people’s days, when they are “done” with their work and then can go home and do other things.

This is not, in ten years of journalism, a feeling he has ever experienced. Doneness, for freelancers, is more like what it is for a steak: a measure of how cooked you are, rather than of how few tasks you have left, which is probably an infinity. If you finished today’s work, tomorrow’s is waiting; if you didn’t finish today’s work, it will loom over you, taunting.

And yet yesterday afternoon, he filed the newsletter for the day, and was left with a strange sense of emptiness, the afternoon and evening stretching seemingly endless before him. Is this how the rest of you have been spending your time?

This morning, we promise to fill at least 20 minutes of those empty hours. We’ve got two pieces for you this week, both pulled from the margins of the city and civilization. Saul’s up first, with a meditation on foxes, forest, and development. Then Asher’s coming back to go deep into the psychosexual undercurrents of Archie Comics.

It's Heat Death. Stay with us.

In The Fox, The Forest; In the Forest, The Fox

Saul Here. When we go on long family road trips, Anush and I have worked out a tacit arrangement with our cats that goes like this.

- If it be daytime, then all feline parties will snooze uncomplaining in whatever spot they can find. (The sunny spot under the back window is usually favorite.)

- If it be nighttime, then enough is damn well enough, and a great ruckus will commence.

Last week, Anush and I were coming back from Atlanta to DC when we hit this particular deadline. Leo was perched on the dashboard, slowly oozing toward the driver’s side windshield which is, I believe he is aware, the worst possible spot in the car for him to be.

By the time we passed Charlotte, North Carolina, Lynx was beginning to meow in protest, an impressive and arresting sound from such a small cat. We pulled off the highway in Lake Norman, a little bit of sprawl a little ways north of Charlotte stretched out between the I-77 and a flooded canyon on the Catawba River, its shores festooned with vacation homes and speedboat docks, that now forms the eponymous lake.

Behind a Quality Inn, we corralled the cats into their harnesses and extension leashes. They jumped down onto the worn asphalt, tentatively at first, then with more confidence, their gaits straightening into the saucy, rolling stroll of a cat on the prowl; their tails sticking up and slightly curled like a shepherd's crook.

We followed them – Anush walking behind me with Lynx – through the tall grass behind an abandoned steakhouse, up along a tall hedge and into an open lawn behind a trailer. A derelict truck sat on a gravel drive; I realized we were probably in someone's backyard, and turned to go. And then Leo pointed.

To have an animal as companion is of course to borrow or share in its particular powers – the TSA agent with a German Shepherd who looks you over in line at an airport can be thought of as a "humandog," a hybrid creature that can scent like a dog but arrest you like a human. Walking with the Bengal cats is similar: watching them watch the world has given us a kind of useless but interesting second-sight for hidden sparrows, approaching dogs, etc.

But this was different. Leo's whole demeanor suddenly changed. He dropped into a hunting crouch; elbows flexed tight to his body; a ridge of fur barely perceptible, in the dark, between his shoulder blades; ears pivoting forward and flattening for maximum 4D vision. Deep in the gathering gloom, pressed against the hedge surrounding the yard we were trespassing in, something moved, like a cutout of darkness laid against another, deeper darkness. A shape like a medium-sized dog that moved with a feline grace.

Asher is of the opinion that between the canids and felines are a number of hybrid forms that – thanks to convergent evolution – combine aspects of both. There is, for example, the hyena – the "dogcat," or a feliform which has evolved to fill a niche similar too, and basically act like, a wolf. And then, he argues, there is its American analog: the "catdog," a canid with the delicate sensibility of a cat.

Known to most of us, of course, as a fox.

Leo, still in his crouch, was advancing to confront the fox, which – it was fully dark now – had now revealed itself to be two foxes, perhaps a mating pair. I scooped him up. "They're bigger than you, idiot," I said. Leo, who has repeatedly stalked deer in Rock Creek Park, warbled a low meow of annoyance and clambered up onto my shoulders. The foxes barked, a surprisingly deep and harsh sound from such a delicate animal; we left them to their evening.

I was smiling as I walked away. There is something magical about foxes, about the way that despite their cuteness and how often they're reproduced in our culture; how they've fit themselves into the niches left by our society, they still feel unassailable wild.

But the other reason why I was smiling had to do with those niches. One of the great unsung qualities of the Southeast in particular is the fast spider web of forest and creek that hides behind the freeways and parking lots and big box stores, casual and unassuming and almost entirely on private land.

In the southeast, as a NC State tree scientist once told me, trees are our default land cover, which means that if you leave a piece of ground alone for long enough it will sprout a forest. And that forest, even in the midst of the Sprawl, as long as it's still connected to the larger breathing mega organism of the greenway, will be the home to staggering degrees of biodiversity, the so-called American Amazon of the Eastern coastal plain.

Particularly in North Carolina, these sorts of creek networks, which Asher and I grew up playing in, have been under threat for some time – for example, I wrote last year about how the biomass industry clearcuts bottom land forest to sell as renewable energy to Europe. When I discussed this with them, industry representatives made two points. First, that they were providing a market for trees that otherwise had none, and therefore, by the peculiar logic with which the American timber industry justifies itself, were creating a financial incentive to keep that land as forest, rather than paving it.

What I always found fascinating about this argument is that it was a perfect example of contextual contagion, wherein a value set used in one register is applied to another one with discomfiting results.

For example, the fact that swamp Cypress trees fetches minimal value at a sawmill when cut down and chipped – a question of how much one is willing to pay for a chopped up old Cypress – somehow translates into a statement about an absolute, actual or moral value for that tree, if it had been left alone on whatever private stand of trees it was on before it got cut down.

Of course there really is no market in living trees or healthy ecosystems – there is only barely a market in carbon, and it's still a very much contested question whether that is the same at all. Asko Lohmus, an Estonian forest scientist I interviewed for National Geographic, was of the opinion that if we treated the question of how we cared for the forests on our property — be it public or private — as an economic question rather than a moral one, then we were going to lose them, because (he said) there quite simply wasn't enough time to create some sort of ecosystem-service based economy in the 10 years or so needed to meaningfully address the climate and biodiversity crises. To arrive at the sets of shared agreements and implicit norms and understandings that make modern capitalism work, he pointed out, took hundreds of years. And we don't have hundreds of years.

And yet meanwhile, the forests are going. And as the timber industry also likes to point out, with rather more grounds, it mostly isn't going to logging but to development, as the sprawl spreads both outwards and inwards from both cities like Atlanta and Raleigh and Charlotte and their countless suburbs and exurbs. The new strip malls and office parks laid out along newly expanded roadways to serve the residents of newly constructed low-density pod-neighborhoods of brand new subdivisions.

It's a process that somehow feels both small and piecemeal and rapid and catastrophic, because for my entire adult life it is meant the gradual filling in, or blotting out, of patches of those quiet forested left alone spaces so characteristic of Atlanta and East Austin, and their replacement with condos and parking lots and office parks. There was the Greenway behind my house in Southeast Austin, a refuge for coyotes and deer and snakes. And then, one day, I came back from an extended absence to find it simply gone, and a shiny new apartment complex in its place. A few acres of forest across the street from the subdivision where Anush's parents live, which was gone one day and over the past couple of years has slowly birthed a gleaming new hospital.

I am not saying that the hospital is a worse use of that land than the few acres of pine forest that had grown over the ruins of whatever prior use the people of Buckhead had put it to. What I'm saying is that I am certain the question was never asked, because our land use discourse offers no real way for the question to be asked. Because as Lohmus suggested, The question of what to do with forests on private property is not really a public question at all.

To a commercial developer, the only fact that matters about a piece of land is what the market will do with it; to a private forest owner, it will be what can raise the income that helps pay the property taxes. And in both cases, virtually the only way to realize any income from that land, or even to avoid paying taxes on it, involves clearing that forest and putting something else there.

And so, as Leo and lynx and Anush and I walked out of that yard, away from the pair of foxes and the screen of trees that hid the forgotten greenway along Caldwell Station Creek; a place unused by humans, where property lines tangled and became irrelevant, and wildlife could eke out its narrow living between the niches claimed by humans. And as we walked up another gravel path, thick secondary forest on our right and tall grass grown up over what had once been truck tracks, I saw what I guess I had always known I would: the mark of that area’s doom. In the last light of day stood a sign declaring the lot was commercial real estate, and it was for sale.

I stood there for a second, and thought of those foxes, and felt like I couldn’t breathe. It felt like two worlds were struggling to occupy the same space. It was, of course, not commercial real estate at all: it was a forest. And yet that forest had no legal existence: on the maps that would determine its fate, it was only a blank polygon zoned for another restaurant.

When that forest is claimed, if it is, the city of Huntersville will get another Chili’s, or a Days Inn. There is no reason why it should not; no hitch in our system as we have constructed to stop that process, which expands in every major metropolis in this country every day. When it does, the foxes will slide back into the surviving greenway, where they doubtless roam now, to face the steady constriction and impoverishment of their world, which is also, of course, our own.

More Heat Death after the jump.

Slow Time at Riverdale High

Asher here. Let’s return, my friends, to Riverdale, and to the question of what, precisely, is up with Archie Comics. To do so, we have to consider the beginning of the development process that Saul describes, and how that gave rise to a narrative engine that keeps on chugging, no matter what color you paint that car.

When the world of Riverdale really got underway in the 1940s, it coincided to some degree with the invention of the “teen-ager,” the carving out of a space between the child and the full adult. By the time the last vestiges of the age of reform died away in America in the 1920s, child labor practices were on the wane, and many children stayed in school for longer. Courtship, practiced under the eye of the family gave way to dating, away from it. The growth of car culture created the sort of consolidated high schools we now take for granted, as well as expanded options for romance and privacy. And, of course, kids could buy their own disposable mass-media entertainment, like—say—Pep Comics #22, starring a certain red-head.

Archie and his friends were not just newly invented characters, but part of a newly-emerging archetype. He was America’s Typical Teenager, cried the ad copy. But what were teenagers, precisely? Who were these people, not yet adults and no longer children, lurching into early adulthood? What were they doing out there, in their high schools built on old farmland, in their cars up on makeout point? And crucially, who were they doing it with? Archie wants Betty, or Veronica, and they want him; but what do they want him for?

Let us begin by remembering that while sexual mores change—and rather more frequently than people like to admit—sexuality has always been complex and multifaceted, especially in adolescence. People start figuring things out. People start wanting things, even if they don’t quite know what it is that they want. Emotions can get messy and misdirected. To be a teenager is to have society open up a space for all of this stum-and-drang, and give you very little guidance in getting through it. Psychosexual dramas, in other words, abound.

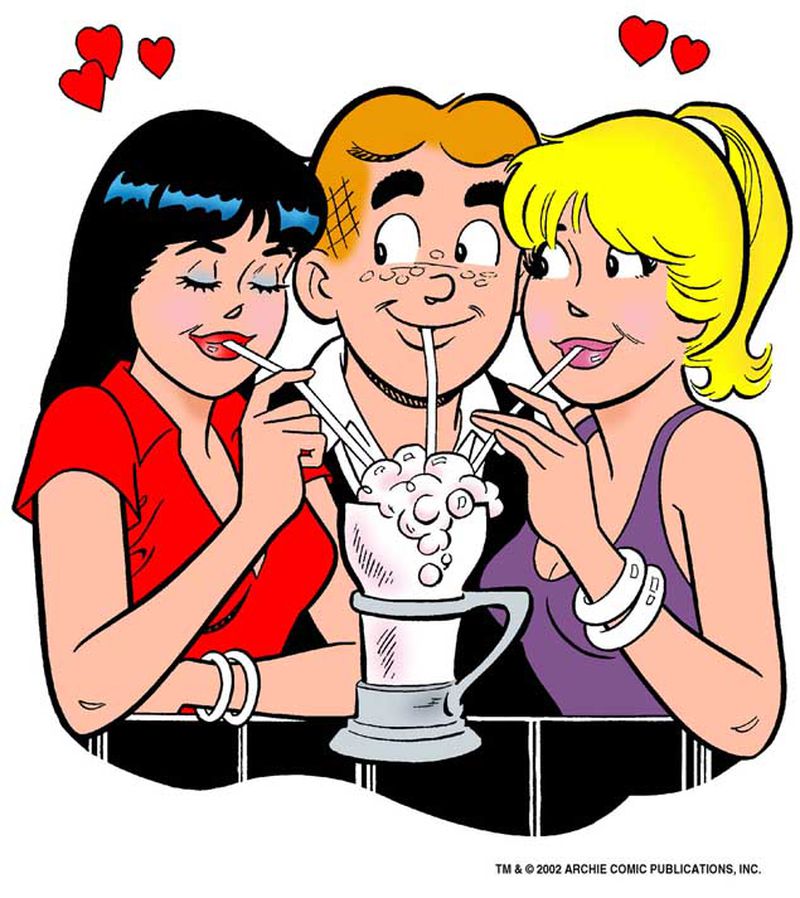

Several such dramas lie at the foundation of Archie, particularly the one between the three leads. Remember: Betty pines after Archie but cannot have him, because he’s usually chasing the wealthy and lovely Veronica. But while the two began as rivals in the 1940s, their relationship rapidly changed into a genuine friendship, albeit one that has a particular ginger-haired friction point. For all that they fight, at this point Betty and Veronica are friends, bosom buddies, gal pals, inseparable and thick as thieves.

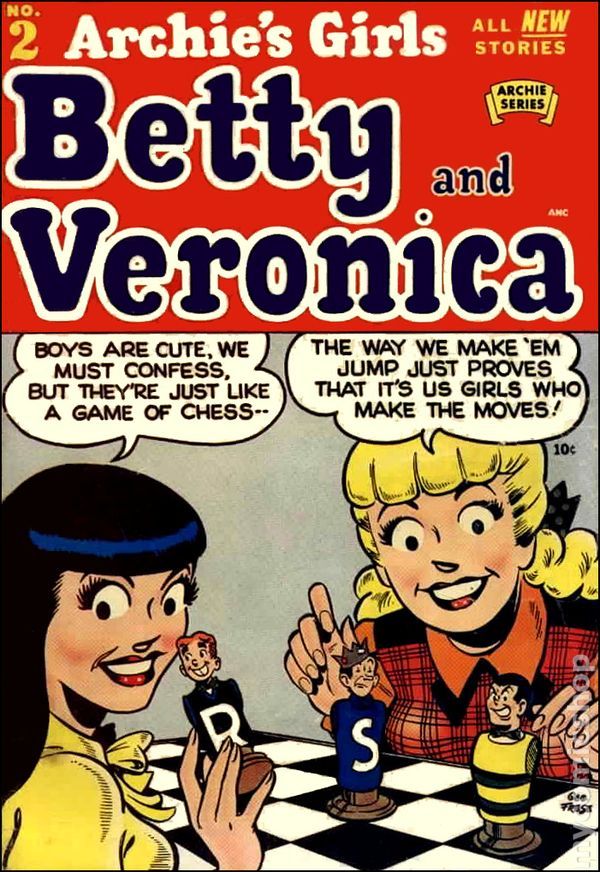

But there’s a fundamental imbalance between the two. Veronica sets the beat in most of her relationships, knows it, and enjoys it: her interest in boys is generally in their role as status symbols, and dating Archie is therefore mostly an excuse to keep him away from Betty. Archie's nearly always going to come running when Veronica calls. Therefore, Betty’s pursuit of him means continually and willingly putting herself in Veronica’s power. (As friend, Heat Death reader and Archie scholar Eden Chubb notes, “If Betty didn't enjoy Veronica winning, it would be odd for her to keep hanging out with her.”)

In fact: there’s reason to believe that if Betty genuinely quit the field of battle, Veronica likely wouldn’t linger either. “What do you find most attractive about Archie?” Betty asks Veronica in 1971’s Laugh #1. Veronica’s response is immediate: “You!”

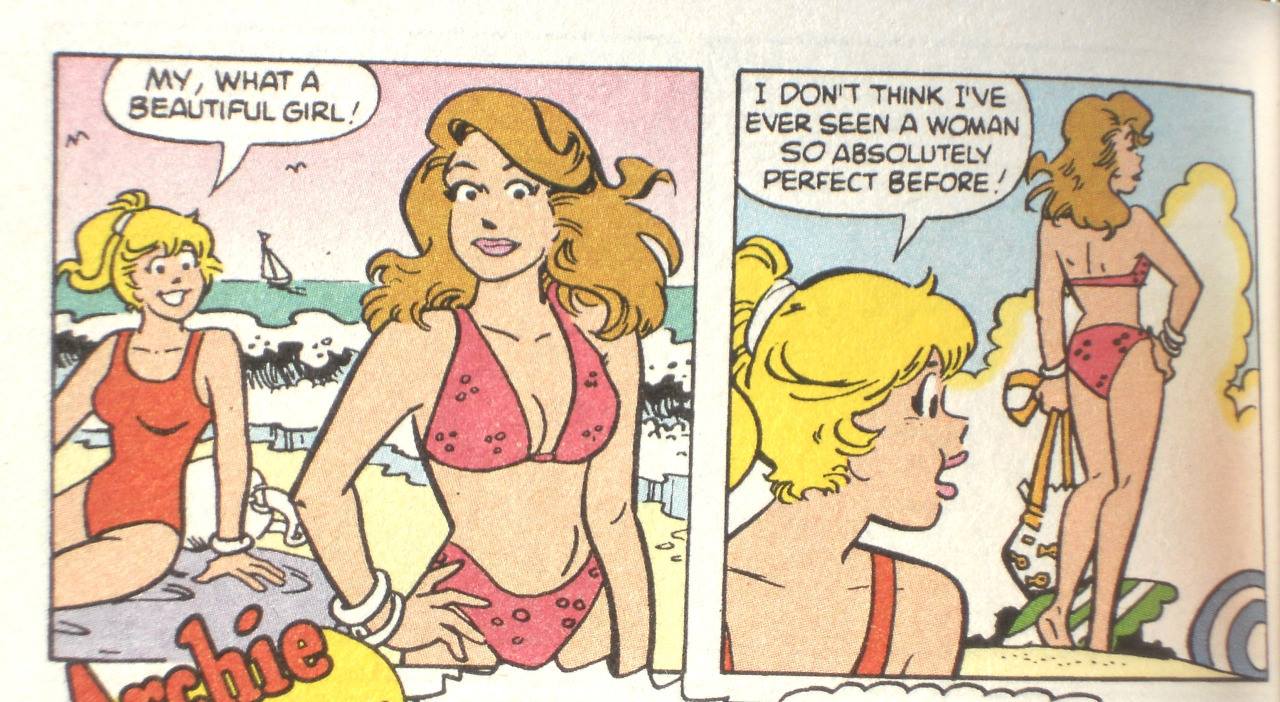

Let’s go ahead and make this explicit. Archie really is not the primary motivator here: what we have instead are two queer girls who are working some shit out over his head. For Betty, Archie is handsome, athletic, absolutely uninterested, and—perhaps!—therefore safe. Betty dates men but rarely oggles them, except when Veronica is around: women are another story. “Look, Archie! Isn’t that a pretty girl?” she cries out on a beach trip in Archie's Digest 79, 1986. “Doesn’t she have a gorgeous body?” Nor is this the only time this happens.

Veronica, meanwhile, favors a more direct approach.

She’s right, is the thing. Archie himself is more a tool of the narrative than a character in his own right. He's a stand-in for a normal teenage boy of a certain era. He plays football. He’s in a band. He’s clumsy, good-hearted (if not always, or even often, actually kind or considerate) and more importantly, he’s there, the utility player passed back and forth and up and down the pitch, anchoring the multiverse of a spinning and constantly changing cast. He is, in all senses, Riverdale’s straight man. That’s the central joke of his relationship with Betty and Veronica: that he thinks any of this is up to him. He's a chewtoy who thinks he gets to pick which dog picks him up.

Of course, all of the characters inhabiting Riverdale are stock characters—the All-American Boy, the tomboy next door, the rich girl from out of town, the comic relief, etc—means that they’re all somewhat mutable and open to multiple readings, which is itself a fancy way of saying that anyone could probably fall into bed with anyone else at any time. (The only exception being Jughead, Who Can Recall His Past Lives, has transcended Desire, broken free of Time, and thus exists in a perpetual state of quiet enlightenment. Nonetheless, there’s plenty of subtext there, too.) The kids are simultaneously chaste and deeply, deeply horny, is what I'm saying; everyone seems to be continually teetering on the verge of a fundamental discovery that never quite arrives.

This recursiveness is actually fairly fundamental to how Riverdale works as a narrative setting. The uninitiated often describe Archie as unchanging. But in fact the world of Riverdale is in constant flux. New characters— gimmicks like Crystal the New Age Girl, supporting cast members like gay-and-elligible Kevin Keller—are continually introduced, even as others fall away. The kids’ fashions change with the times. The art style drifts in subtle ways. There are full-on narrative and stylistic reboots, such as the one occurring in 2015. It’s actually closer to the truth to say that Riverdale is a ship of Theseus adrift on the swells of time, a continually re-built palimpsest of a certain vision of America. Anything and everything can and will change, save this: there are kids. They are in high school and date, in every conceivable permutation— except for the ones that might actually resolve the whole business.

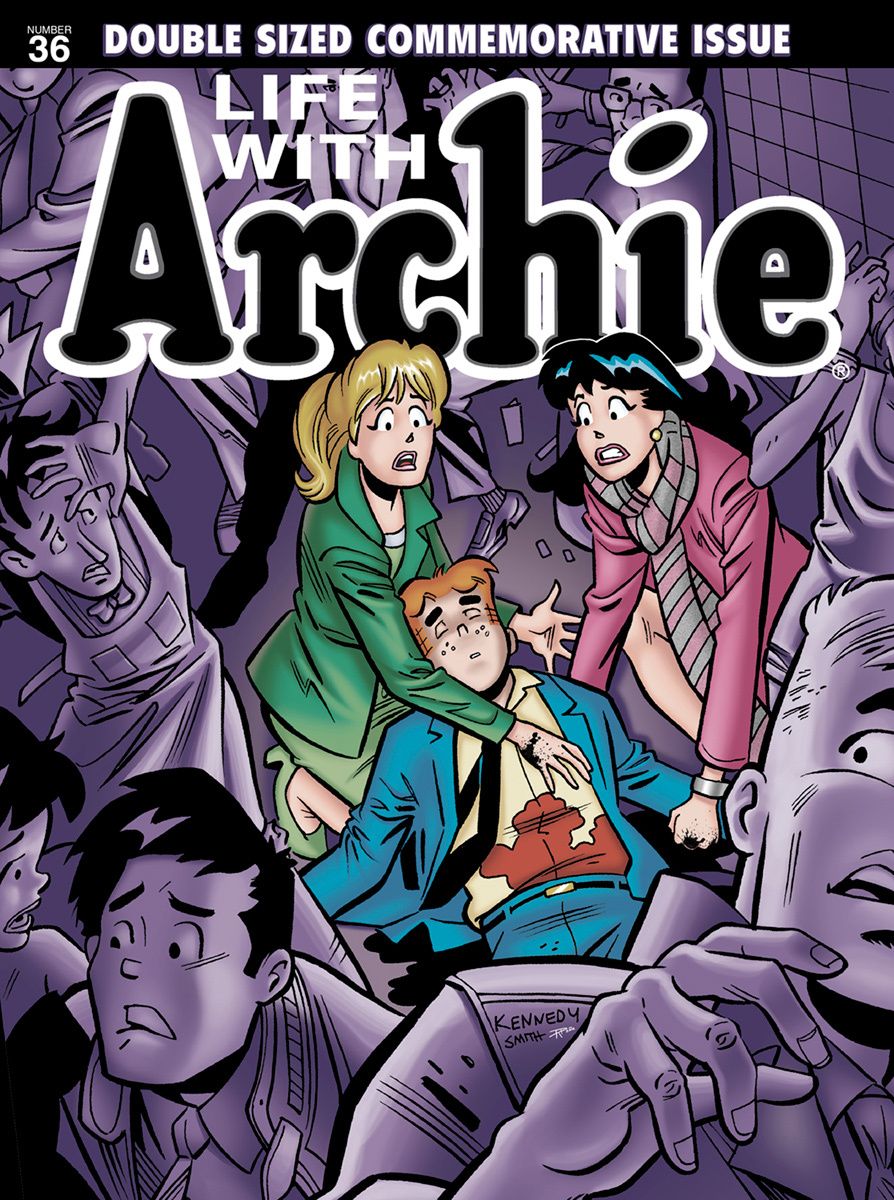

Is this high school as purgatory? Certainly I remember the long and structured days of 10th grade, when it seemed my whole life was contained inside brick walls and bells, and that I would never be getting out. Everything around me—inside me, too—was changing, and yet there I was, in the same place, day after day. And yet there were four summers, and four proms, and I was gone. What awaited beyond was past the scope of the space we call “teenager,” and the world began to move much faster beyond the threshold. In the 2010 volume of Life With Archie, the narrative split into two timelines: one where Archie and Veronica married, and another that saw him with Betty. Nobody seemed particularly happy or fulfilled. In 2014, both strands ended in the same place: Archie bleeding out on the floor of the malt shop, dying in Betty and Veronica’s arms. The next year, the comics rebooted. The wheel of reincarnations spun. Riverdale persists.

There’s a darkness here if you choose to look for it. Once the teenager had been invented, the role had to keep being reinvented, through high school comedies and sex farces and horror films, through Dawson’s Creek and Pretty Little Liars, Buffy The Vampire Slayer and Veronica Mars. Somewhere along the line teenagers became older, sexier, played by people in their twenties or (hilariously) thirties. The Teenager was now a person adrift on the world, correctly suspicious of authority, honored and punished for revolt, old before their time, staring down the barrel of calamity. The kids aren’t alright. Nobody is.

Thus, when Archie came back to television, it came back in the form of CW’s Riverdale, which begins with a body washing up on the overcast, pebbled shore of the Riverdale Reservoir and the arrival of rich girl Veronica Lodge. Soon Archie and his friends are enmeshed in a bubbling pit of drama, cheating, heartbreak, dysfunction and—gasp!—murder. What are America’s typical teenagers up to this week? Dispensing vigilante justice. Fighting bears. Going to prison. (Betty and Veronica share a kiss, because it’s that sort of show, but nothing ever comes of it, because it’s that sort of show.)

And yet for all the madness on screen, the whole thing is rather an empty exercise. There’s simply nothing radical about peeling back the skin of wholesome America and pointing at the maggots underneath. Nathaniel Hawthorne was puncturing the religious hypocrisy of the Puritans in 1850. Sinclair Lewis’ 1920 novel Main Street skewered the much-hallowed American small-town as bleak, ugly and smugly conservative. In 1972, Ira Levin’s horror novel The Stepford Wives delivered a definitive depiction of suburban, white-flight America as a viciously reactionary and patriarchal project.

In 2010, Arcade Fire released The Suburbs, an achingly sad rock album about the void stretching between farm and city, an inescapable, empty place full of empty people. Riding across the country on a Greyhound Bus in 2011, 19 years old and lost, I listened to The Suburbs on repeat, tears stinging my eyes. It brought me back to my own childhood in Plano, Texas, and the days I spent running the wild fringe of creeks between the parallel ranks of McMansion Hell. It was a world of marching sprawl, built on dreams of easy credit, and already teetering on the edge of collapse. Cruelty in the middle schools, drugs and entitlement and suicide in the high schools, death and penury and addiction beyond...

The darkness in this country was never under the surface. It's only that there are those who have chosen not to look at it. Those who have chosen to wrap themselves in innocence, in bright colors and simple lines and wide, wide eyes. To imagine, you might say, that they live in Riverdale. Because for them, everything’s Riverdale: high school will never end, they will never have to choose, they will never have to step out into the world that’s coming, and they will never have to die.

But the Riverdale of Archie Comics is a subtler and stranger place than that. Leave aside the comics’ dedication to introducing people from all walks of life, as part of a vision of a polite and cosmopolitan America. It is also a place of wanting, of trading of power and erotic gazes, of a constant push and pull, as wrapped in repeated and formalized ritual as any BDSM club. There is, as Eden pointed out to me, a radical safety in it: a place where complicated and fraught dynamics can be explored without particularly high drama or great heartbreak. A place designed for teenagers back when that was a new thing, a place that does not grow in the sprawl, a place where you can lock lazy eyes with your best girl over the rim of a soda malt, the guy you both want betwixt you, but never really between you. And one day you’ll both go off to college and have a serious talk and an even more serious makeout, and discover the whole rest of your life.

It’s going to end someday. Everything does. That’s fine. In Riverdale, you can take as long as you need.

That's the bell. This has been HEAT DEATH: If you like what we're doing, please feel free to drop us a line at brothers@heatdeath.xyz (And if you've got friends you think would like this, why not invite them to sign up?

Member discussion