Festival of Fires

The officers should have been expecting trouble.

It is about 2200 years ago, in the province of Judah, a hilly backwater passed between a long succession of greater West Asian empires. A large group of farmers and townspeople gathers — curiously, fearfully — in the central plaza of the market town of Modi'in, a few days' journey west of Jerusalem.

These peasants and artisans have come down from their homes and fields to see a detachment of officials from the pagan king, Antiochus IV, who rules in faraway, glittering Damascus. Antiochus, latest son of the Seleucid Dynasty, is a reformer and empire builder — one of several feuding kings engaged in a great game for control of the shattered empire of Alexander the Great. Now, in a troublesome backwater of the empire, he is laying down the law — engaged in a bloody attempt to quell subversion in Judah. And, perhaps, to drag the religious fanatics there into the modern world.

This detachment is here to deliver that change. The officer leads an animal which is to be offered on the town altar in the name of the king. The text recording this moment doesn't tell us what the animal is, but tradition — and what came next — suggests that it was a pig. To many in the crowd, that meant unclean meat: abominable in the sight of the Lord of Hosts.

But to King Antiochus and the Jewish reformers who support him — or whom he supports — it is a sign of a new ecumenicism, in which all throughout the empire may offer sacrifice to any god at any altar, local prejudices be damned.

The townspeople now face a wrenching choice. Refuse to sacrifice and offend one mortal king — or agree, and offend the other. The Lord Almighty is theologically all-encompassing but frustratingly incorporeal. The soldiers of the mortal king have swords.

The crowd grows restive, then angry. Before long, the situation explodes. Unclean blood splashes the altar, though it does not belong to any pig.

The act of killing — and the many that come after — still live on in Jewish memory, celebrated every winter with candles, chocolate coins and fried potatoes. But it also serves as an early stroke in a long war, one that would ultimately tear down the ancient, cosmopolitan Mediterranean cultures of blood sacrifice and pagan worship — including traditional Judaism.

In its place, something else would rise: hot and flickering as firelight, slippery as oil, and unbending as hammered bronze.

Saul here, wishing you all a Happy Hanukkah from Heat Death, the newsletter that knows the reason for the season.

The winter solstice finds the Brothers Elbein huddled in their respective corners of Austin, bearing the onslaught of a continent-spanning winter storm that’s come howling out of the Arctic. It’s damn cold, in other words. But the storm also serves as a sort of seasonal-climatological conspiracy: pushed by a vast and uncaring mass of hot air, the winds bear down on us at almost precisely the night of the solstice — an icy front hammering our homes on the longest, darkest nights of the year.

On these nights, Jews around the world gather to celebrate Hanukkah, the Festival of Lights.

Hanukkah is a confounding holiday: hard to define, easy to dismiss. Gentiles tend to treat it as an adjunct to Christmas. Some Jews agree, deriding it as a consumerist imitation of that all-consuming holiday. Others treat it as a winter fortress raised against the prospect of assimilation, or an up-jumped minor holiday promoted so Jewish kids could hold their heads up in front of the Gentiles. Liberal and lefty Jews often half-jokingly refer to it as a celebration of fundamentalism triumphing over cosmopolitanism. "Were we alive at the time of Hanukkah," the riff goes, "the rebels would have killed us."

And yet. Recently the three year-old daughter of a close friend announced that she "didn't like Hanukkah, only Christmas."

This came as a surprising blow. My friend is secular; she hadn’t thought that she cared.

This year, we’ve spent every night of the holiday lighting candles and giving gifts with that little girl and the other children of our little, growing tribe. On the third night of Hanukkah, the Austin Soviet was full of adults and children eating stuffed smoked salmon latkes (recipe to follow), drinking cider and engaging in what in other circumstances might be called "holiday cheer."

And our cheery party that night — just like any other holiday party you might have gone to — sits at the far end of a long strand going back to that plaza in Modi'in. A knife flashes in the Classical age. And in the metal we can almost see, reflected across ages, the face of a little Jewish girl in a Gentile country, reaching up to light the menorah.

Today we're going to take a deep dive into the story of Hanukkah: of how a fundamentalist insurgency largely fought between Jews became the official holiday of secular Judaism — and how it helped to birth the modern world.

Let's return to that plaza in Modi'in, where the Seleucid officer stands ready to bring the community into the king's new Commonwealth. In practical terms, that means ensuring that these commoners understand the new rules: that any altar is to be available to any worshiper, and any sacrifice — even those the Jews consider unclean.

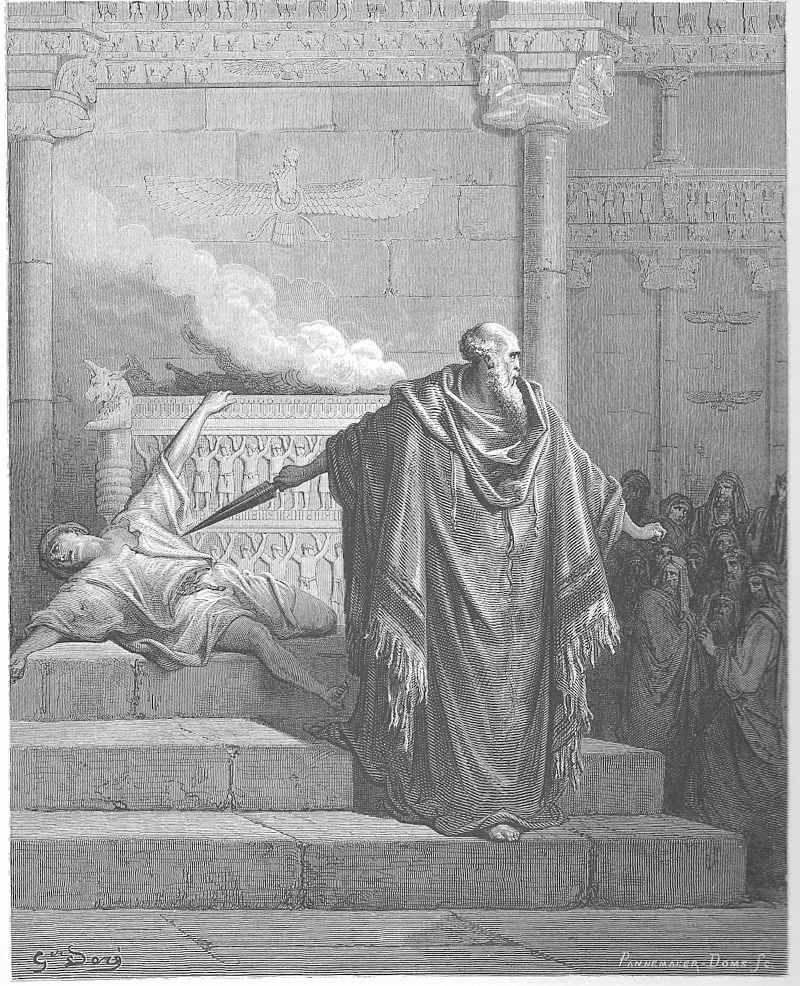

Surveying the crowd, the Seleucid officer picks out a local big man: Mattathias, a well known, prosperous local priest, who stands in the crowd surrounded by his large adult sons. In the familiar mode of an empire suborning a local leader, he offers the old man respect and riches if he'll carry out the sacrifice.

"You are a leader, honored and great in this town, and supported by sons and brothers," the officer says. (We’re drawing here from First Maccabees, one of several contemporary literary accounts). "Now be the first to come and do what the king commands, as all the nations and the people of Judah and those who are left in Jerusalem have done."

The crowd tenses: They know Mattathias and his sons. The family are hardline religious conservatives in the growing intellectual civil war between Jews over how much to embrace Greek culture — and over who will control its spoils. The old man fled his prestigious job at the Temple in Jerusalem, amid the bloodshed that had accompanied the religious reforms. Perhaps old Mattathias thought he could retire to the countryside. Perhaps he came to foment revolt. In any case, now Antiochus' modernizing campaign has followed him here, to the provincial town that’s the base of his power.

Facing down the officer, Mattathias spits defiance. Antiochus' other Judean subjects can forsake their own religion to worship Zeus if they like, he tells the officer. But his family? No. "I and my sons and my brothers will continue to live by the covenant of our ancestors,” he said.

Mattathias isn’t the only one in danger here. For years, the books of Maccabees tell us, people living in Seleucid-controlled Judah have been killed for far less — intransigent Jews murdered as potential traitors on the orders of the paranoid king. People in the crowd know that if nobody makes the sacrifice, the swords on the officer’s hips are likely to come out.

So as the community holds its breath, a local man steps forward.

We know nothing about this man: not his name nor patronymic; not his profession, faith or politics. He might have been a Hellenist, genuinely committed to the King’s campaign of dragging Judaism into the modern era. Or perhaps he simply saw the danger facing the community if someone didn't pick up that knife. Perhaps he chose to sacrifice his own morals, as it were, on the altar of collective survival. An altar, after all, can be torn down or reconsecrated. Human life, once taken, can never be repaired.

Either way, it was a fatal decision. As he took the knife, Mattathias pushed through the throngs. As a priest, he was by definition a professional killer — a man whose job description rested in large measure on his ability to dispatch and dismember large animals, quickly and efficiently. Before the stunned soldiers and the frozen crowd, he stabbed the Jew to death — and then turned and killed the official who led the delegation.

This was a stunning provocation. The province of Judea was no stranger to political bloodshed among Jews. But killing a colonial officer — that was a bridge that could not be uncrossed.

"Those for God, to me!" Mattathias called, and he and his sons fled the bloodstained plaza for the caves and defiles of the high country. There they began a long, grinding rural insurgency — a dirty war of murdered officials and plundered storehouses, ambushed patrols and brutal reprisals. Mattathias's son Judah, called Macabee — the Hammer — soon emerged as a gifted war-leader, a master of the forced march and surprise strike. After his father died in the hills, Judah took over the rebellion.

Within the first year of their campaign, the Hammer surprised a force led by the Seleucid governor of the neighboring province, killed him, and took his sword. In the second, his men struck an even larger army — one strung out along a narrow pass into the hill country — and routed them. In the third, he made a nighttime raid on a Seleucid camp, sending them fleeing in disarray back down to the coastal plain.

In the fourth year, Judah and his brothers took Jerusalem. They captured the Temple, and reconsecrated it to the one God in the old way. Later, their family would reign over it as priests and kings: a new Jewish monarchy to govern a free and independent Judea for the first time in five hundred years.

The victory of the Judean rebels over the Greeks was a miracle, later consensus agreed: the triumph of the few over the many, the righteous over the profane, et cetera.

But it isn’t the miracle we celebrate today. That one was noted much later. According to a legend written down in the academies of faraway Babylon, hundreds of years after the war, Judah's men entered the Temple and found it dark. The eternal flame at the center of the great gold menorah was out. All that could be found to light it was a tiny vessel of oil — just enough (the story goes) to burn for a single day, when it would take eight to produce fresh oil of sufficient ritual purity to be used in the Holy of Holies.

The men lit it. And rather than gutter out after a day, it kept burning, on through the second day. And into the third. Fourth. Fifth. Sixth — yes, it's still going, can you believe it — seventh. And finally the eighth, when fresh oil could be brought and the laws of thermodynamics restored.

And so every year, on the lunar anniversary of the triumphant entrance to the Temple, across the world, Jews light their menorahs, and eat foods fried in olive oil, and give little gifts. Night after night, for eight days.

What I've just laid out above is the myth of Hanukkah, as I learned it growing up thousands of years later and half the world away, in a modern Orthodox Jewish community in Atlanta, Georgia.

By myth, I don't mean it isn't true — though there are plenty of reasons to question the story above. I mean it's a story where the historic truth is irrelevant, because it serves as a structural element in a larger culture.

For Jewish kids growing up in the Southern Baptist South, the Maccabee story served as it had for centuries — a piece of rebar hammered through the concrete walls of American Judaism, a fortress from which we could look down upon a world that was reflexively unlike us. More generally, Hanukkah served as a primary holiday of a particular American secular nationalism, a direct statement of religious independence. You might call it an (ahem) leading light in the low-key civil rights campaign that transformed December from “Christmas” to the more secular “the holidays.”

Or did it? By the time I was growing up, Hanukkah had become just as plasticky and consumerist as Christmas, a vector by which Mall America — the country’s actual religion — infiltrated Jewish culture. (Not that I minded the video games.) We could celebrate Hanukkah if we liked: it was just another holiday brand, and no business minds having a diverse range of brands on offer.

Nor do the old myths themselves now seem so useful. At some point — years after I had left the Atlanta shtetl, when I had been living and working and sleeping among the people I had known as Christians — the sheen began to wear off the triumphant Hanukkah story.

I have to blame the first phase of this on our dad, Brad Elbein, an attorney with a skeptical take on the miracle of the oil. Wasn't it interesting, Papa Elbein liked to ask, that no one recorded the oil miracle for centuries after it allegedly happened? Almost as if it was just a handy political myth cooked up by the surviving Maccabee brothers — once they became kings and priests in Jerusalem — as an official miracle to justify their usurpation of the throne.

Or consider the relative values of the Maccabees and their enemies. The "Hellenized Jews" of the story — like the would-be sacrificer that Mattathias killed — were described as the ones who wanted to betray the faith of their fathers. But in the backwash of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the idea of hilltop religious reactionaries fighting a liberalizing Western empire took on rather different resonances than it had when I was a kid. The Maccabees felt like, say, the Afghan Taliban — heroic in battle and committed to their faith, perhaps, but not the architects of any society I would ever want to live in.

Hanukkah thus stands at the intersection of some strange cultural crosscurrents. In November 2001, months after the 9/11 attacks, as U.S. soldiers fought in Afghanistan, George W. Bush recited a speech at the lighting of the official U.S. menorah.

Asked about the latest video from cave-dwelling insurgent leader Osama bin Laden, Bush gives a long-suffering shake of the head, and ad libs the perfect Gentile perspective (at 5:23) on the holiday: "I couldn't imagine somebody like Osama bin Laden understanding the joy of Hanukkah, or the joy of Christmas, or celebrating peace and hope."

Which raises three immediate objections:

- Hanukkah = Christmas, eh? Who's setting the agenda in that relationship, pray tell?

- Are we to believe that Judah “The Hammer” Maccabee thought he was inaugurating a season of peace?

- You're telling me Osama bin Laden, the man leading the fundamentalist revolt in the name of an uncompromising and anti-cosmopolitan vision of the One God — a pampered child of the modern and alienated West, embracing fantasies of a pure macho swords-and-sandals past to wipe away the compromises of a comparatively limp and degraded present — you think that this man doesn't understand the meaning of Hanukkah?

You wouldn’t know it from the American Jewish Hanukkah myth, but the Maccabee revolt did not end with the Hammer’s capture of Jerusalem. Instead it dragged on another twenty-odd confusing, bloody years. Judah pillaged pagan cities and destroyed pagan shrines along the coastal plain, and fought the peoples of the pagan provinces around Judea. He abandoned and recaptured Jerusalem; signed a pact with Romans that proved, in hindsight, a bad move; he died in battle. Eventually his brother Simon, the Wise, reached de facto independence — the Seleucids maintained the face-saving fiction that he was military governor — before declaring, with Roman support, the beginning of his own dynasty, the Hasmoneans.

Almost immediately, the Hasmoneans began playing the game of thrones with the same zeal as their neighboring dynasts. Simon the Wise died when his son-in-law Pompey bar Abobi murdered him and his two sons at a banquet. Under Simon’s descendants — who would eventually style themselves kings from the line of David — Judea rose to become its own petty imperial state.

The Hasmoneans went to war against their neighbors, settling old scores and bringing God's law (as they saw it) by force to their neighbors in Edom, and among their stay-behind cousins in the north. Eventually, they were just another form of the oppressive terror that old Mattathias had risen against. The dynasty’s last real king, Yonatan Hyrcanus, burned the competing temple of the Samaritans — Israelite cousins of the elite who resettled Judea — on Mount Gerizim, near what is now Nablus. He doused their flames to the One God, and told them at sword-point that any further sacrifices would be made in Jerusalem, on Southern territory. He also led a campaign that forced the people of nearby Edom to convert to Judaism, complete with forced circumcisions.

He forced them, as his great great grandfather was said to have spat at the king's officer so long before, to abandon the faith of their fathers.

By the end, Mattathias’s descendants were yet another squabbling, incestuous and murderous Mediterranean dynasty. And like most of those dynasties, they ended up getting swallowed back up by a larger, meaner imperial power. At the end of the family’s long decline, they mortgaged the kingdom their family had fought so hard to take and retain. A pair of Hasmonean brothers whose names don't bear remembering fell out over the succession. The loser invited in the Romans, who installed him as puppet-king in his brother's place. They would not leave again for more than 600 years.

Over the course of that long Roman occupation, the legacy of the Maccabees bore repeated, deadly fruit. Jewish patriots and zealots led three separate wars against the empire — attempted reboots of the Maccabee uprisings known as the Jewish Wars, aimed at restoring Jewish monarchy on Jewish land.

All were complete and unmitigated failures — a succession of apocalypses, generations apart.

The first attempt came in 63 C.E. Jewish rebels rose up and enjoyed a brief, deadly success. They paid for it as totally as can be imagined: Roman armies under Titus burned the Temple during the sack of Jerusalem; crucified tens of thousands; killed and enslaved hundreds of thousands more.

Then, in 115, rebels in the Jewish communities of Libya and Egypt rose in a war of religious extermination toward the Greek communities against whom they had struggled in the streets for generations. They smashed temples, overwhelmed Roman garrisons and unleashed a spasm of conflict that depopulated wide swaths of the Mediterranean coast.

Finally, in 136, a charismatic revolutionary named Shimon Bar-Kosiva, who styled himself Bar-Kokhba — Simon Star-Son — led a final grab for the throne of the Maccabees. Recent evidence suggests that his revolt also began for the most Maccabean of reasons: the Roman decision to rebuild the sacked Jerusalem as a modern imperial city. At the heart of this new city rose a pagan temple; an edifice erected to Jupiter/Zeus, the most high of the Roman pantheon.

Like the Maccabees, Bar-Kokhba routed the empire’s armies from Jerusalem, and then threw them out of Judea. He gathered in idealistic Jews from across the Diaspora, who joined his new independent Jewish state. He minted coins. One of the era’s great sages declared him the Messiah.

Then the legions returned in force, and the land paid in blood. “50 of [Judea’s] most important outposts and 985 of their most famous villages were razed to the ground,” the Roman historian Dio Cassius later wrote. “580,000 men were slain in the various raids and battles, and the number of those that perished by famine, disease and fire was past finding out.”

Thus, he concludes, “nearly the whole of Judaea was made desolate.”

When I say that the Maccabees make bad heroes, this is what I mean: their vision of pure worship and self-righteous military supremacy, backed up by a vengeful God, provided a disastrous inspiration for later rebels. The rebellions that followed the model of Maccabee glory led to the total destruction of everything Mattathias had fought for: every facet of the Judean pretense of monarchy and glory was ground into dust. The people of Judea lost as they never had under Antiochus.

The ripples of that loss were greater than the question of who held the throne, however. The last rebellion cut short millennia of the Judean martial traditions, which had put Judean mercenaries in armies and pirate ships around the world. Worse, the victorious Roman empire — eager to decisively settle the Judean issue — made Jerusalem a fully pagan city. The people we can now truly call Jews were banned from entering it.

That was a terrible insult, a blasphemy. But the devastation was worse even than that. The Temple was gone. The high priest and his acolytes; the lords of the meat, who oversaw our offerings to the divine; they were wiped away. The Romans had ripped the heart out of a major strand of Jewish tradition. It is hard to describe the immensity of the resulting psychic wound: we bundle it into a capricious word. Exile.

From one perspective, then, the Maccabees who rekindled the sacred fire also lit an accidental fuse — one that blew up the Temple and form of religion they were so attached to.

From another, they lit the forge that made the form of religion that replaced it. In the academies of Palestine and Babylon, long after the Macabee rebellion and the fall of Jerusalem, the burgeoning Rabbinic movement codified the laws. Alongside them, they worked out a mythic structure: one that the decentralized communities of the Jewish diaspora would rely on to survive as a single, self-conscious nation.

About five centuries before the Maccabee uprising, in the days of Babylon and bloody-handed Assyria, the Jews had been split between two rival kingdoms. Each was ruled by a different monarchy, and each claimed that theirs was the sole legitimate shrine at which animals could be sacrificed to God. There were other religious conflicts as well: the stories of the Prophetic books record endless conflicts between regional shrines, traditional Canaanite and household deities, and the priests of the centralized Temple in Jerusalem.

The Temple priests of Jerusalem conclusively won that war, at least for a while. Over four hundred years, under independent Jewish monarchies and supportive foreign rulers, the Jerusalem priests established their role as sole intermediaries between God and human — the only ones who could kill and burn the animals required by Biblical injunction in a way that God would accept. The Hasmoneans carried that war even further.

By the time of the first Judean revolt against the Romans, therefore, there were no other sanctified altars, no other places to carry out official sacrifices. There was only the Temple. And when the Temple burned, the Jews — already scattered across the Mediterranean and near East — went from being a people with one legal shrine to one with none.

This, as we’ve noted, tore a hole in the center of the faith: a great absence that recalls the empty room that once stood at the absolute center of the Temple itself— the Holy of Holies, a space believed to contain the infinite presence of God.

As the Temple was built around this hole in the world, the religion we now call Judaism was rebuilt around the hole left by the loss of the Temple.

The result was a quietly stupendous remaking of the practice of Judaism. Under the guise of extreme conservatism, the religion changed radically from one built around animal sacrifice, agricultural tithes and the obsessive maintenance of spiritual purity — to what we now call Rabbinic Judaism, a model built around prayer, textual study and communal gathering. Jews mourned the loss of the Temple, and this mourning helped bind the dispersed communities together as the actual temple (state-controlled, corrupt, and constantly subject to disputes over proper ritual) never could.

Early Christianity performed the opposite trick: maintaining a religious structure remarkably similar to Rabbinic Judaism, and every bit as far from the Temple worship — while pretending to throw out the Biblical commandments. For centuries, Christians also gathered communally for prayer, kept their Sabbath, and studied both the Bible and a collection of newer theological and historical texts. The fire that both movements threw at each other was in part an attempt at deliberate speciation: enforcing the boundaries between two faiths and communities that were initially at constant risk of collapsing back together.

This paradigm — the skillful use of apparent similarity to mask dramatic shifts — is a key ingredient in modern Judaism: a kind of necessary kayfabe that allows almost infinite change so long as certain forms are observed. The "Hebrew" calendar I had grown up with was the ancient calendar of pagan Babylon, with names drawn from the pantheon of Tammuz and Ishtar. The serif-heavy Hebrew block lettering of the Torah scroll was, in fact, the Imperial Aramaic script, which adorned official documents in the sequential empires of Babylonia, Assyria and Persia. The word for synagogue is Greek, and the Jewish practices of diligent text study — divination through criticism — bear striking resemblance to the obsessive study of old texts in dead languages by the pagan scribes in Damascus and Babylon.

And where did those Babylonian influences come from? Well, half a millennium before the Maccabee saga, Judaea launched an ill-advised rebellion against the King of that Empire. In return, Babylon burned down Solomon's Temple and deported the elite of Jerusalem to their capitol, then perhaps the greatest city on Earth. There in the metropole, or in outposts of the empire, through dynasty after dynasty, the majority of Jews would remain, metabolizing foreign ideas and reworking them into Jewish clothes — while announcing straight-facedly that nothing had ever been different.

To put that another way: The Maccabees presented themselves as restorers of an eternal Torah and sanctifiers of an eternal Temple. Their God was intolerant and obsessed with policing the lines between his and other cultures — perhaps because there was so much foreign that the Jews had adopted in their generations of Exile, and likely long, long before.

The flame itself is a particularly ironic example. One influence the Jewish communities would have experienced in the East in the centuries before the Macabbean revolt was the faith of the Magi, the monotheistic Persian state religion in which a light-bearing Creator strove in constant struggle against darkness and the forces of the Lie. In the fire temples of the Magi, an eternal flame burned — an endlessly stoked, vigilant protection against a swallowing dark.

This has obvious Jewish resonances. When I was told the Hanukkah story as a child, I alway imagined that the lamp they were lighting was a menorah — but it wasn’t, exactly. Instead, it was the Ner Tamid, the Eternal Flame prescribed by Leviticus, that burns today forever in the heart of every Jewish synagogue, as it once burned in that long-gone Temple in Jerusalem that those rebels fought their way into.

To the Maccabees, the eternal flame burned in the name of the one god. But it was similar to other flames burning at the same time, across the world. In the temple of Rome at Vesta, the temples of the Greek gods, or the fire-temples of the Magi of Persia. Even as they sought to slam the doors on other cultures entering Judaism, they were carrying forward another tradition, at once esoteric and universal. Another branching on the great menorah of culture and life.

There is a paradox here, of course. Hanukkah as the holiday of proud revolt, and Hanukkah as the holiday of the Jewish dispersal, which was caused in a large measure by that inspirational image of those revolts.

The paradox bears important structural weight. Like the absent Temple at the heart of modern Judaism, the stories contain two important and opposed ideas: that darkness will come, and that fire will burn it away.

It is also a paradox that — however destructive its example might have been — was too powerful for the rabbis ultimately to suppress. So they did their best to tame it, and in the Hanukkah miracle they encoded a subtle and powerful parable of greater long-term use than any history of nationalist rebellion. The story is thus no longer about the war: it is about a specific moment in time, a story of light in the dark.

It goes like this.

The Maccabee rebels fight their way into the darkened Temple. Before them lies the darkened husk of the Eternal Flame, without enough oil to keep it going. Further down the road lies tenuous, temporary victory — which will only be a brief punctuation along the history of grinding defeat, and the daily compromises of survival.

In that holy room — as the rabbis recorded — they face a wrenching choice. Before the darkened lamp, there is the practical option: leave the lamp unlit. Permit the sanctuary to remain dark and unsanctified until supplies were secure. Or light the flame, using what oil they have, and stand and watch while it gutters out.

Knowing their efforts must fail, they take the first step. They light the flame. The oil catches. We can imagine fire dancing through the oil without consuming it, like the burning bush that greeted Moses in the desert, the glorious transgression of light shining forth without accompanying death. The candle reveals itself as something more than simply biomass oxidized and consumed in the presence of destructive decomposition of aerosolized oils but as a slit in the fabric of the world through which the great light shines, as it shines still through the flames of every menorah across time and space.

Until, eventually, the proper oil can be brought, and a safer and more secular divinity can be returned to the sanctuary. The terrible light of God recedes, so that human power and agency might, again, replace it.

Leaving, baked into the walls of Holy of Holies, the memory of that Eternal light: a reflection of which burns on windowsills across the world tonight.

Every fire, one fire. A shimmering reflection of that burning in the center of every temple, every hearth, every cell. A line of candles handed to that generation as they would hand it to their children, as one flame to flame was passed in a line from that first fire that lit the land, so long ago, as life emerged from water at the beginning of time.

Though darkness growls outside, we kindle ourselves a flame.

Happy Hanukkah, everybody. If you'd like to give us a gift, why not grab a paid subscription and help keep us going?

Member discussion