Halloween Heat Death Spooktacular

Look. Over there, in distant lands, in places that slouch between between the real and the imagined, between here and there: crossroads, shorelines, derelict houses, lost cities, back alleys.

Something is stirring out there. Out in the swamp, black water stirs and bubbles, and huge forms shift among the shivering trees. Out on the high crags, weird wings unfurl. Out among the graves, dirt buckles and writhes, disturbed by a knocking underground. Out in the vast depths of the starlit ocean, undreamt terrors sail over infinite emptiness.

There’s a darkness outside of town. There’s a shape at the corner of your eye. You can feel it, can’t you? The boundary lines are being crossed; the unknown is bleeding in. These are monstrum: portents, warnings, deviations from natural law. But nature is vast, and laws are a human dream.

What is a monster? It is an invitation. Come and see.

Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that's proficient in both the Monster Mash and the Transylvania Twist. (Like so many things in life, it's all in the knees.) A slight nip has finally entered the air here in Austin, and the leaves are beginning to tumble from the tree branches. After a thoroughly brutal summer, the arrival of autumn is a breath of cool, fresh air, and both of us are feeling refreshed.

Being raised as Jews of the Orthodox persuasion, we didn't grow up celebrating Halloween. But it's hard not to feel some affection for it. Halloween is the one American holiday unburdened by shmaltz, smarm, or tedious obligation. It's not really an occasion for sanctimony; indeed, sanctimonious people tend to dislike it. But as far as we're concerned, any occasion that combines 12 foot skeletons, sexy or esoteric costumes, and the disembowelments of decorative gourds has much to recommend it.

Of course, there's another reason to like Halloween: it's an occasion to celebrate monsters, occult occurrences, and the lingering uncanny. We're big fans of a good spooky story. And being working writers, we've told a few over the course of our careers. So c0nsider this edition of Heat Death a grab-bag of Halloween tricks and treats. Inside you'll find hand-picked stories from Asher and Saul's archives of work, including cryptids, ghosts, killer doctors, and mass graves. Asher is also republishing some musings on monstrosity, and — as a special treat — a gallery of some of his spookier illustrations.

It's Heat Death. Join us. We hope you have a... bloody good time.

Torn from the Elbein Archives

Bobby Mackey's Music World is the most haunted honkey-tonk in America, full of nasty legends, reported specters, and a genuinely grim history. Everyone's fascinated by the place's reputation as the only music joint with a hellmouth in its basement. Everyone, that is, but Bobby Mackey. — Asher

The skeletons of Latin America's past loom over its future, and the evil done to them does not sleep. Under an army base in Guatemala, a gruesome discovery leads to a modern-day ghost story. And like most ghost stories, it hinges on a question: can the dead help hold the living accountable? —Saul

The weeping ghost has many names and many faces, but the most famous is La Llorona. Her history may run deep into the past, and the horror she represents is more personal than many give her credit for. But one thing is always the same: don't let her catch you by the river alone. — Asher

A blood-soaked spree across Dallas reveals the horror at the center of Texas's system of medicine: a man whose patients died under the knife, and a medical board that continually stood by and allowed it to happen. — Saul

Jefferson claims to be the most haunted town in The Lone Star State —while being quite vague about a certain subset of the people who died there. It's a haunted place, alright. But not quite for the reasons its tour guides think. — Asher

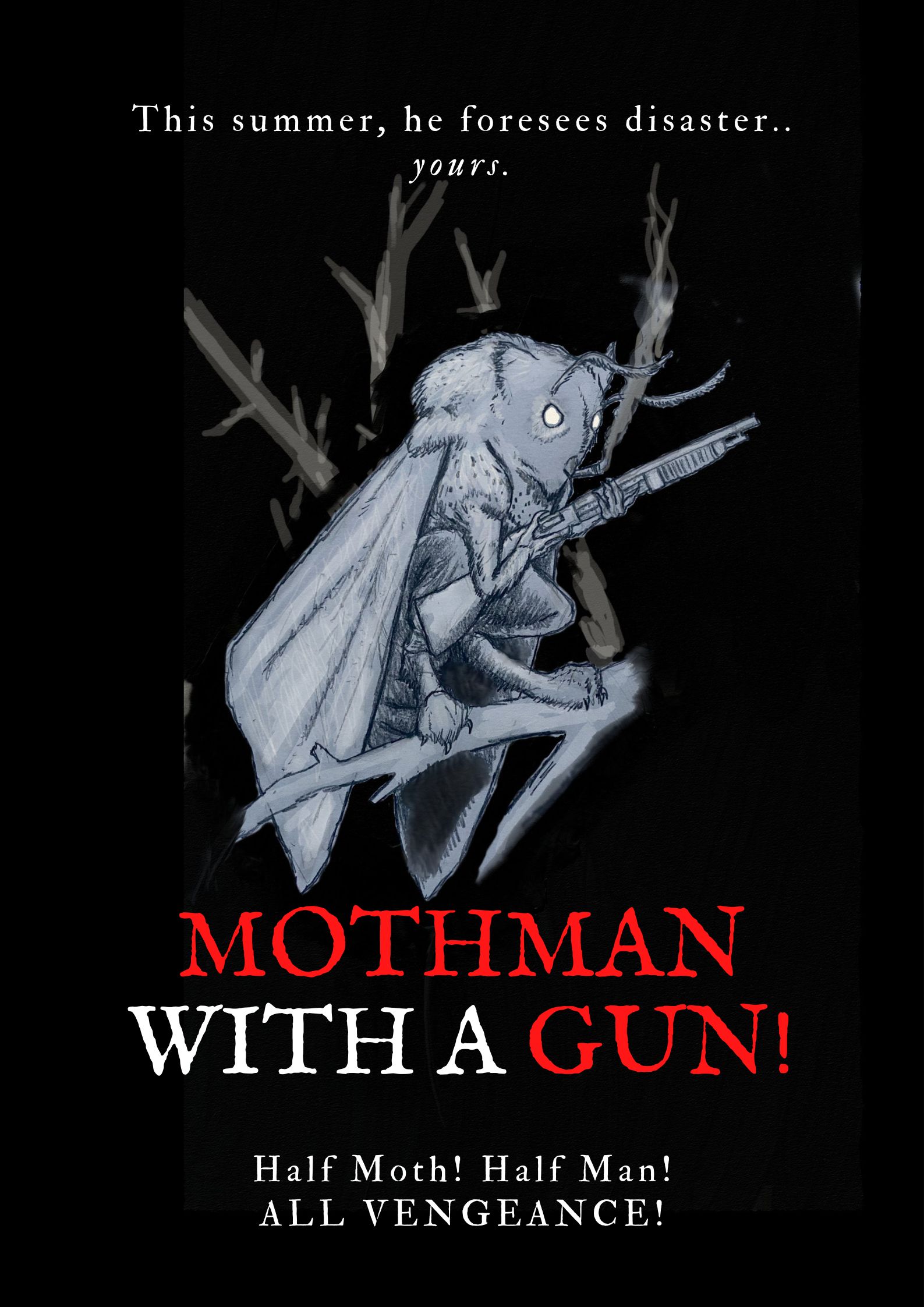

Mothman has haunted Point Pleasant for decades. But what is the mysterious cryptid? Or perhaps it's better to ask... whooo is it? — Asher

The Monster Mash

Asher here. A while back, I was moved by strange inspiration (i.e a theme month on Twitter) to write on the nature of monsters. I concluded several such entries in a fugue state before sanity returned, making fulfillment of the rest of the prompts quite impossible. I am left only these few tattered missives. Make sense of them...if you dare.

Monstrous Geography

A monster isn’t a monster if you see it every day. For much of history, traditional peoples living on the landscape have seen big cats and crocodiles as facts to be worked around: inconvenient, dangerous, and imbued with spiritual meaning. But big predators, for all their myriad fascinations, are not deviations from any natural order. For us to encounter a monster, it must either have left its natural home—Grendel rising from the mire to execute world’s bloodiest noise complaint, Dracula leaving his castle in search of new and excitingly British bosoms—or we must, ourselves, go somewhere we are not meant to be, like a black lagoon or the depths of space. Someone, in other words, has to go somewhere. Some has to step across—to literally (and latinly) transgress.

Monsters, therefore, dwell beyond veils and depths. Where the forest or jungle swallow the light, scattering sightlines in layers of leaf and shadow. At sea, months from sight of land, or 20,000 fathoms down. In bleakest desert or the highest mountaintop, or in black caves plummeting to the roots of the world, where unseen things lurk. In the creaking silence of an abandoned building or castle, where the halls are a maze that draw you ever further, ever deeper, and history weighs on your every step. In Transylvania, the land beyond forests, and Skull Island, a jungle behind a wall behind a thousand miles of crashing, murderous sea. In back of beyond, and behind the thrice nine kingdoms.

Far enough to be hidden. Close enough that someone…or something...can step through.

The Monster Arrives

Some believe are only two types of stories: a person goes on a journey, or a stranger comes to town. Generally, this is nonsense: there are no monomyths, only multiple reflections of common human experiences. But it’s true with monster tales. Monsters are — as we have seen — symbols of transgression and boundary-crossing, and thus they require somebody to go somewhere. Sometimes, that means a monster appears in a story genre that does not typically have them: historical fiction, family drama, crime thriller, romantic comedy. Their appearance can be a shock, or they can be woven into the fabric of the story from the beginning. But the appearance of a monster transforms the story utterly. From Dusk Till Dawn is defined by the sudden appearance its vampires, after all, and it’s hard to care that much about the marital infidelity in Peter Benchley’s novel Jaws considering the fact of the shark.

Monsters are therefore a narrative threshold that cannot be uncrossed. You thought you were in a world of of frock coats and familial obligations, where the strictures of life bind us but seldom surprise us. (What’s that prowling on the moor?) You thought the heist was dangerous, trip-wire-taut logistics all that stood between you and prison or a bullet. (What’s that scratching at the vault?) You thought it was summer, and graduation was a year away, and the ocean looked so cool, so inviting...

Once a monster arrives in the story, the world has broken and remade itself. Once a monster arrives in a story, it is a monster story. Always.

Speaking With Monsters

We speak to communicate information: ideas, emotional realities, the complex or simple thoughts that swim inside our skulls. There are linguistic differences, of course, and words and cultural concepts that are difficult to translate. But when you speak to another human, even divided by a chasm of language, you are speaking to someone who has the capacity to understand you because they are you. There is some common reality—a shared humanity, if you like—upon which the two of you can land.

At the end of Predator, a bloodied and muddied Dutch stands above the broken body of a hunter from beyond the stars, a crab-faced reptile whose green blood stains the forest leaves. “What are you?” he asks. The guttural reply comes back: what are you? The words are there, but the intent is orthogonal, alien: is it mimicry? Is it a genuine attempt at connection from something uncanny? Dutch will never know, and neither can we.

With apologies to another Austrian philosopher, who spoke originally of lions: If a monster could speak, we would not understand them. And perhaps, if you can understand them, they aren’t a monster at all.

Monstrous Attire

In urban fantasy and its associated genres, the monster — or, more often, the creature that sometimes behaves monstrously, as all people have the capacity to do— often appears in a t-shirt and jeans. Vampires might go in for a suit and tie (or clubwear) and werewolves generally wear flannel, but by and large, the nonhuman dress with studied casualness, like a tech billionaire in busted sneakers. Narratively, they might be trying to pass as human, or maybe they just like how it feels. But the subtext is generally clear. Things that dress like us resemble us in all the ways that matter: can be befriended, romanced, argued with, folded into the social framework. The clothing is a humanizing element. It’s not so much that things of a terrible and eldritch nature can’t wear a TeeFury t-shirt. But however little we might understand the person in the fabric, the fabric itself is knowable, and imparts some knowability, or the illusion of knowability, to its wearer.

Clothing is not, in and of itself, the sign of personhood. But we often correlate the two in uncomfortable ways: there can be a hideous vulnerability in nakedness, and to be dressed in rags, or barely dressed at all, jibes with cultural narratives of the worthy and refined. The poor and unhoused are monsters to the rich, inhuman things identifiable by their rags, their patches, their worn and dirty clothes. The monster becomes a person when they dress as people—the right sort of people—dress. Clothes can make a monster into something like a human. They can do the opposite just as easily.

Domestication of the Monstrous

Imagine a dragon bred from wild stock over generations, its flames dulled but not stilled. Imagine the ornamental fish-men, selected for flowing fins and more extravagant color, swirling like overgrown koi in a pond. Consider the cockatrice, the effect of its stare reduced by time and careful engineering to a pleasant soporific, pecking in the yard. Domestication takes the unknown and smothers it in the human bosom: we might imagine that if it’s domesticated, it isn’t a monster.

But of course this isn’t so. If domestication is a state, than it must have boundary land, and if it has a boundary, than a monster can cross it. My parents adopted a dog once—big and shaggy and sleepy-eyed—who, upon being brought to a dog park, fixed her eyes on a toy poodle and changed as surely as a werewolf feeling the full moon’s touch. I dragged her away before she could hunt that poodle down and kill it. Her teeth snapped the air. Her spittle flew in ropes. In that moment she wasn’t a dog but a predator of no little size, and the more terrifying for the transformation. (She later trapped my father in the kitchen, teeth bared and murder in her gaze; when she calmed, they took her back to the no-kill shelter. To this day they refer to her as "Cujo.")

“Domesticated” doesn’t mean “not dangerous.” It merely refers to that which we have brought into our homes. Sometimes, the danger lies where we’ve forgotten to look.

Vampire

The coffin lid opens. The villagers shrink back. Some of them have been plagued with dreams of the dead, a terrible shape standing over them, pressing against them, bloated hands and genitals on their frozen bodies. A flash of teeth or a sharp tongue in the dark. Now their fears are confirmed: the body lies contorted in its winding sheet, bloated and ruddy, teeth and hair and nails extended, black blood streaming from its lips. The dead should be still. The dead should be quiet. The dead should be dead. Yet this body has been overtaken by life, an orgy of consumption in the dark: a mindless, churning drive to consume and breed. A vampire.

Later, vampires come to inhabit castles, high society, posh nightclubs, sanitized wet dreams. Their uncanny preservation becomes a thing of cold, marbled muscle and perfect, chilled breasts. Their perfection is gained and kept at terrible cost. They are personifications of excess, of corruption, of a greed so insatiable that even centuries of predation cannot quench it. Capitalists and feudal lords, producing nothing, feeding on blood and stolen life. What do they have in common with that rotting peasant, wrapped in their winding sheet, gasping out a graveyard stink as the stake goes in?

Just this: The life in them is not our life. They are human shaped, but no longer human. Their preservation is a lie. They are all, fundamentally, dead.

Lycanthrope

The iconography is very good, which is what you’d expect out of something that’s essentially a Hollywood creation. Full moon hanging ominous and bright in the sky, silver bullets shining like captured moonlight, a body wracked and convulsed by grotesque change. It’s visually very neat: there are a ton of ways to get from human to wolf-thing, and special effects artists have tackled all of them with gusto and enthusiasm.

Conceptually? The folkloric idea of werebeasts—were-hyenas, were-tigers, etc—places its emphasis on dangerous, man-eating predators hiding among us in human form. As our industrialized culture has grown more abstracted from the wild, however, the modern conception seems largely predicated on the notion that bestial passions are just waiting to overtake the delicate rationality of the human mind: the urge to fight and fuck, to engage fully in an unleashed carnality. Homo homini lupus, and all that. It projects human neurosis onto wolves, which—while certainly dangerous animals, and not to be trifled with—are rather retiring creatures at heart. But then, a wolf with a wolf’s mind is a threat. A wolf with a human mind is a nightmare.

Gillman

He’s a craggy thing, that Gillman, made of ridges, bones plates and nobbily scales. The mermaid is a being of chimerical desire, sinuous and sleek, and while her tail is finned, her face is a human’s face. The Gillman is not so easily bisected: his inhumanity is painted evenly on a bipedal canvas. He is not half this or half that. He is wholly himself, whoever that is.

His true fishiness dwells in his flat, cold eyes. The glassy stare of the goldfish and the grouper suggests a being devoid of inner workings: aquatic automatons, free-swimming vegetables. But what scans as emptiness is only mutual incomprehension. It has been 375 million years since our tetrapod tribe forsook the waterways and struck it out on foreign shores. (To a fish, all shores are foreign.) There is a divide between our most distant aquatic cousins and us—they inhabit a world unlike ours, with rules unlike ours. It’s human arrogance to say that the Gillman somehow bridges the gap. He is the gap.

Maybe, if the woman swimming through the still waters of the Black Lagoon understood the way that fish speak—the delicate and courtly turn of a fin, the shimmer of a scale—she would look down and truly see the thing sculling beneath her, an old thing entranced by this most removed relation: a fish that has lost everything fishlike in itself.

But fish are invisible to us. And so, blithely, she swims on.

Alien

Outer space is fantasy of colonization. We will leave the crowded old world in imperfect ships, make dangerous voyages in search of new planets, new lands on which to build and reshape to our will. These lands will be empty, terra nullius, to do with as we see fit. We will change their atmosphere, strip them of their resources, and use them to fuel our way out to the next world, and the next. What is the frontier there for, if not to be tamed? What is emptiness for, if not to be filled? We call it space because that’s what it offers: endless room for us to roam, and for our children to roam. It is mankind’s destiny to go among the stars.

And yet there are stories of what happens when the stars come to us. Of vast ships appearing out of nowhere in our skies, bearing technology we cannot match, opening us to their designs like a knife blade opens an oyster. Of metal leviathans sliding through the soundless void between creation, each a predator nation consuming everything in its path. Of cold-eyed things that look at us and see nothing sapient, nothing alive, who perform horrors upon us and call it science, who take our men or our women, who use us like beasts, who kill us in pursuit of their own relentless expansion. Of things we meet during our own wanderings in the outer black, on planets we have claimed but hold no claim on; things that see our bodies as nothing more than meat if we’re lucky, and nests if we’re not…

The final frontier is endless. The final frontier is hungry. Perhaps it’s better for everyone if, for once in our lives, we stayed put.

Angel

Be not afraid. The sky splits in thunder; the doors of heaven’s vault crash open; blinding light rains like spears across the ground. Be not afraid. Something is coming through, a rocket dropping through layers of reality, a celestial body burning through re-entry. Be not afraid. Those who have been visited describe it as a ball of eyes, rotating around and through one another, lashed by whips of flame. Or as lion-headed, eagle-winged, a tangle of limbs tipped with slender, expressive hands, the forms superimposed on one another, limned with ultraviolet so vivid it burns the eye. Be not afraid. It is not, without great effort, shaped as we are shaped; even walking among us, its skin sparkles as the physical molecules of the air cascade and react to its flesh, exploding like microscopic suns. Be not afraid. It is lovely in the way a volcanic eruption is lovely. Be not afraid. Lovely like a mushroom cloud, like the radiance of a supernova, like the colors of the setting sun setting the polluted horizon aflame. You are small; you are kneeling, shielding your eyes, hot tears burning your cheeks. This is right. Be not afraid.

It does not speak to you in words, but it comes bearing a message. The message begins: Be not afraid. As if, upon being visited by an angel, you could ever be anything else.

Flowers

Consider the carnivore plant. The sweet sap smell that leads to unwary to an inescapable pit, where the water stings, burns, digests. The leaves that snap shut in a cage, salivating pulp pressing soft and spongy against your liquifying body. A perversion of what we consider the natural order, one that gives birth to tales of man-eating trees, toothed flowers, sweet-talking space seeds crooning for a nibble of blood. Pretty straightforward, really: a fear that the life which surrounds us, omnipresent and foundational enough to define whole biomes, is just waiting for its opportunity to take a bite. (Plant-blind as most people are, it’s not like we’d ever see it coming.)

But most plants—save those desperate species that live in impoverished soils or difficult situations, the sort that force you to grab your nutrients directly from passing bodies — have no need to act so precipitously. We live animal lives, fast and direct and frantic. Plants can afford to await the nutrient pulse, the flow of fertilizer that runs from dropped dung and decaying carcasses, passed along through hidden roots and secret bargains. Death feeds plants as much as sunlight. Die in the forest, and the trees will eat you. Die in the meadow, and the wildflowers will bloom that much brighter. Sooner or later, everyone feeds the plants.

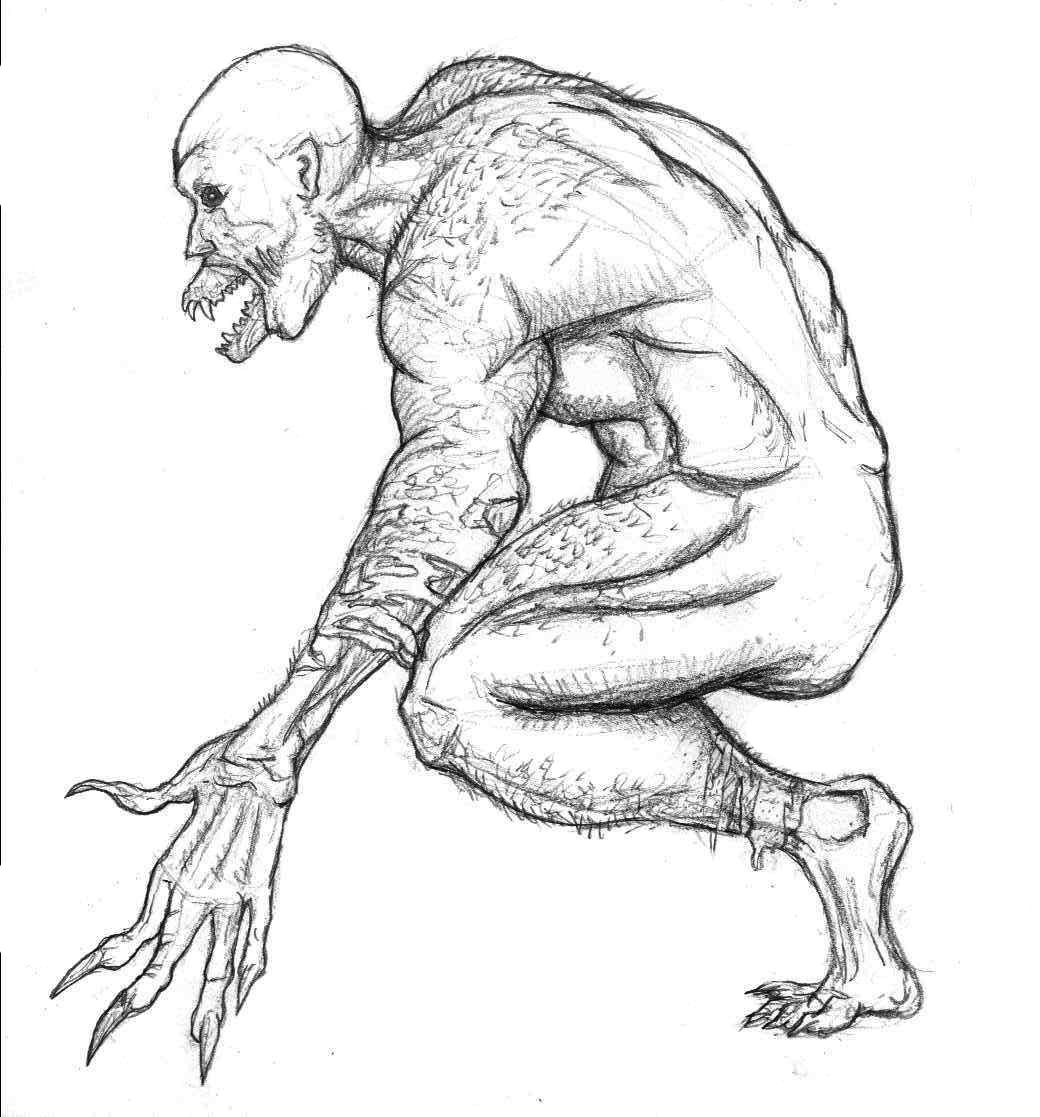

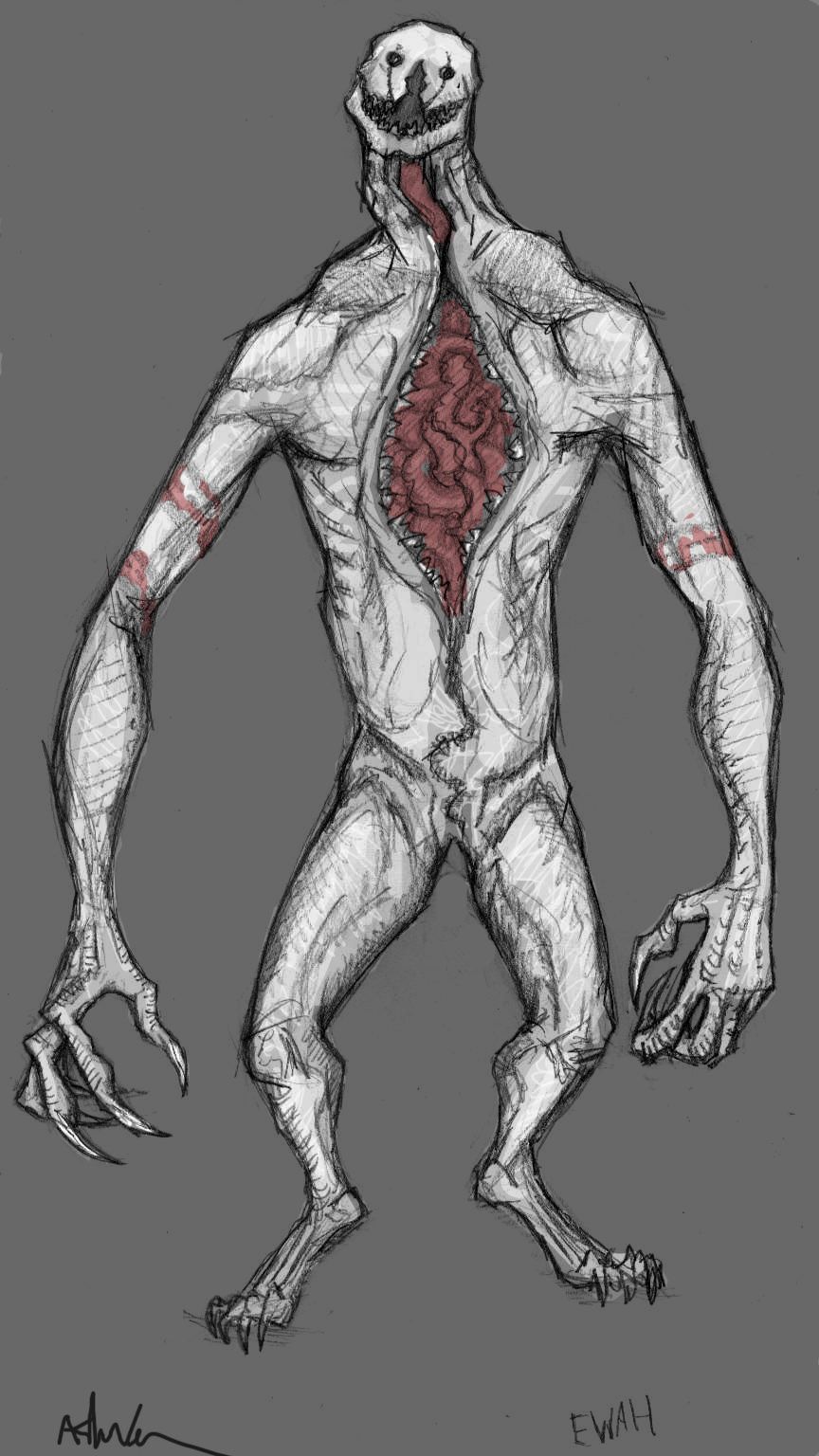

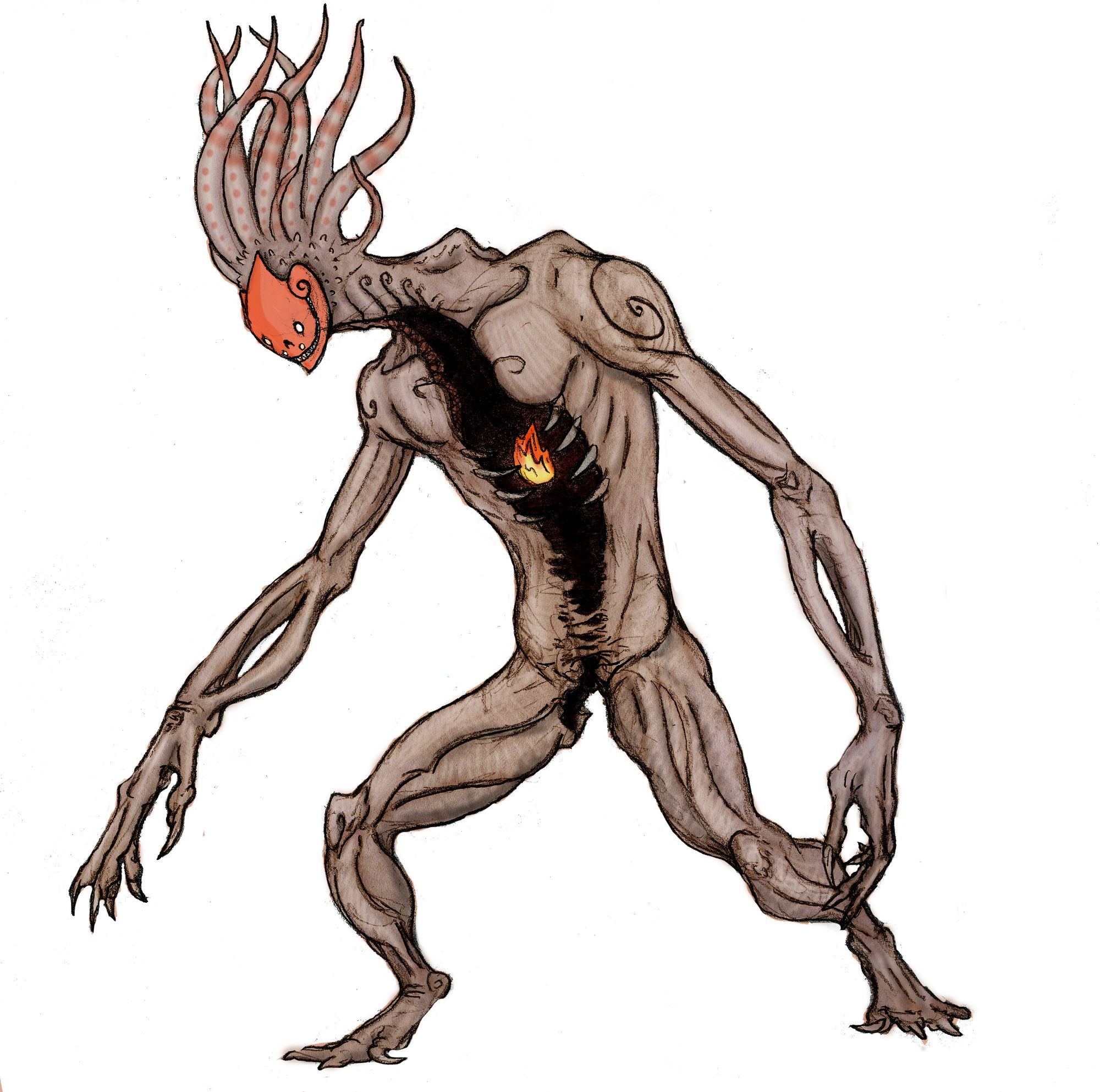

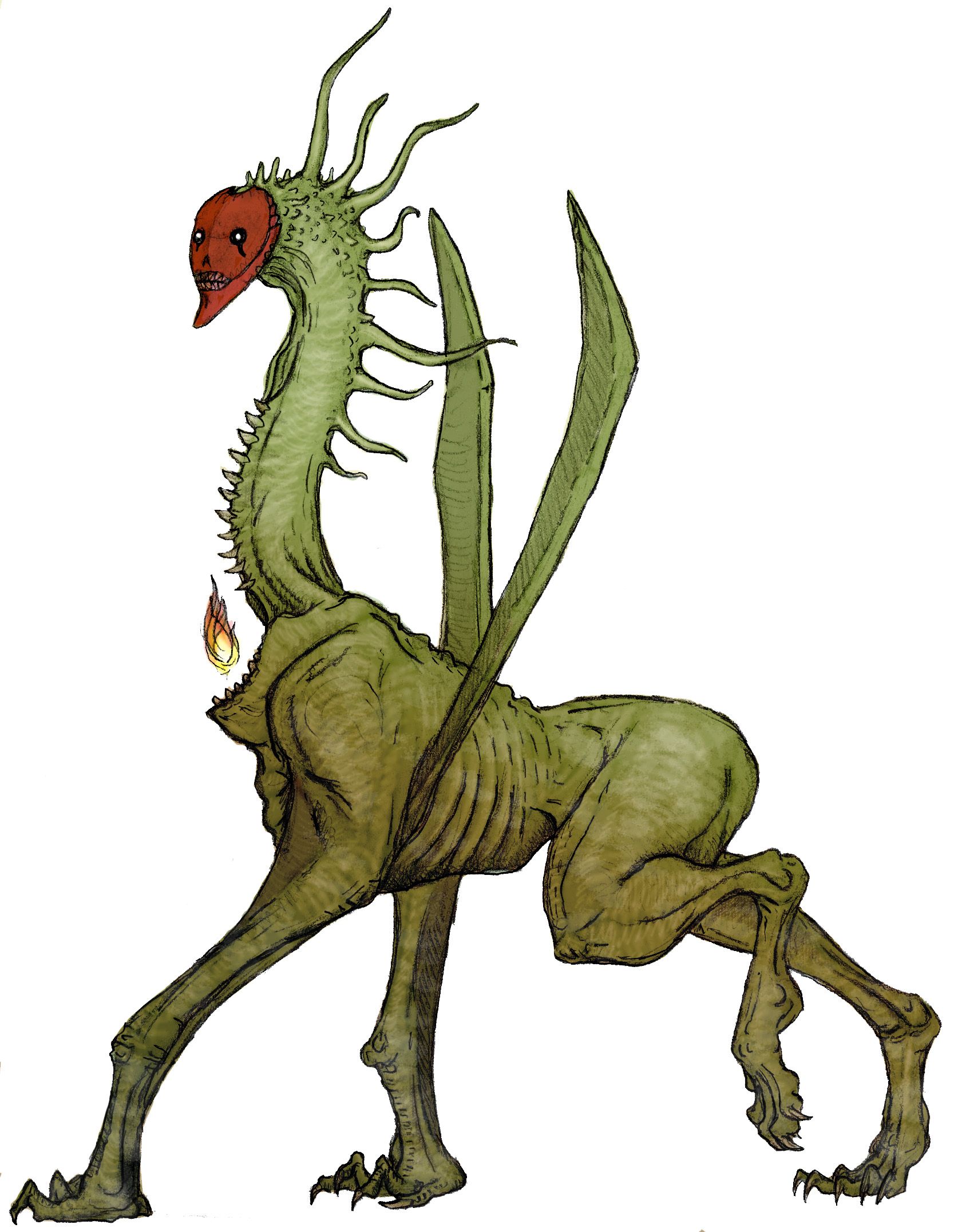

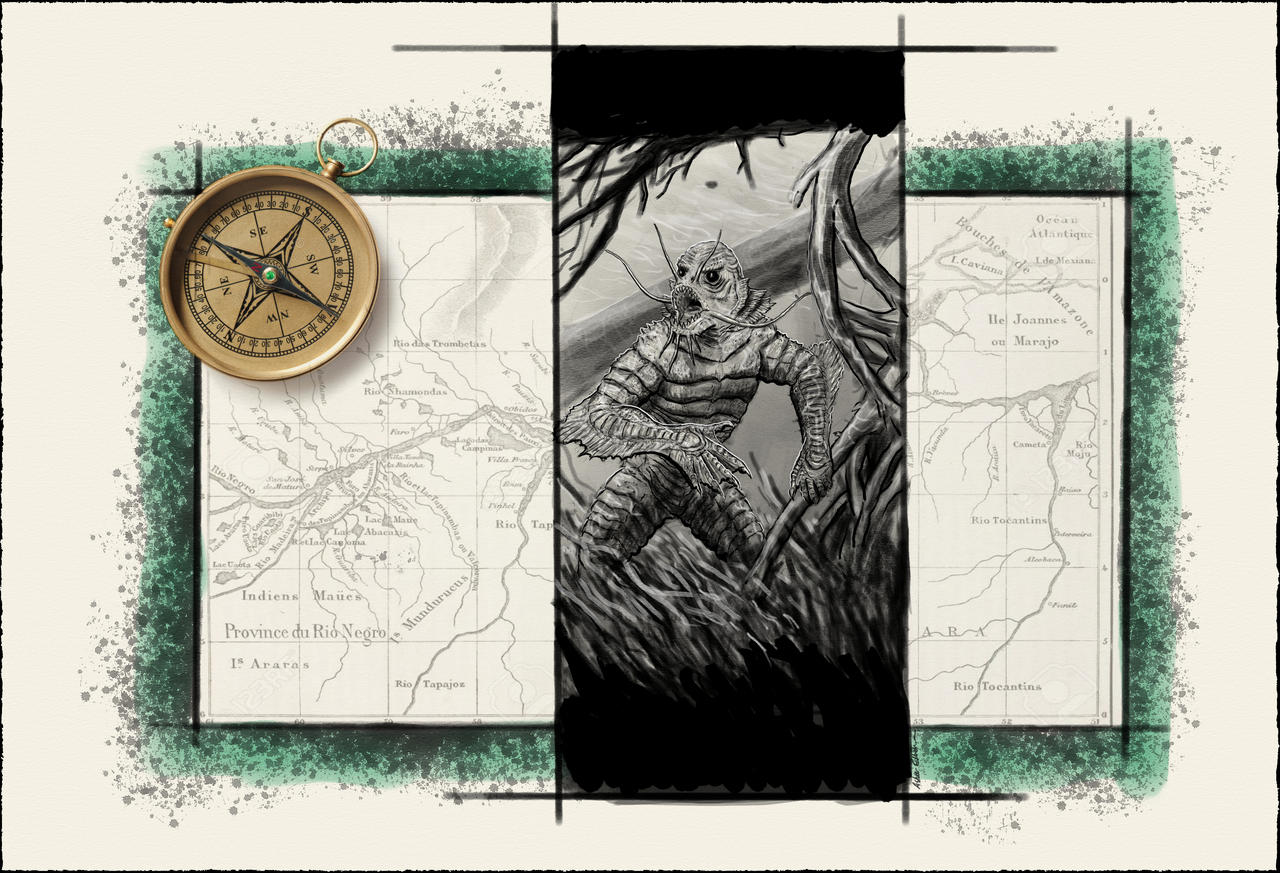

Visions of the Monstrous

Asher here. Again. Over the past two decades, I've often turned my hand to more graphic pursuits — albeit mostly as a hobby. And as a hobbyist, one of my favorite things to do is draw monsters. They're a good way to practice anatomy, while also being rather more forgiving then depicting the strictly mundane. (Nobody minds if a monster looks a little bit wrong, after all!)

Here, then, is a collection of some of my favorite critter images. Some are scary, and some are a little silly. But that, after all, is part of the fun. To see more of my art, check my Deviant Art site here.

That's this week's Heat Death, everybody. If you want to support us, don't forget to sign up at the link below. Free or paid memberships are available, and either is greatly appreciated.

Happy Halloween!

Member discussion