Inaugurating the Cabinet of Curiosity

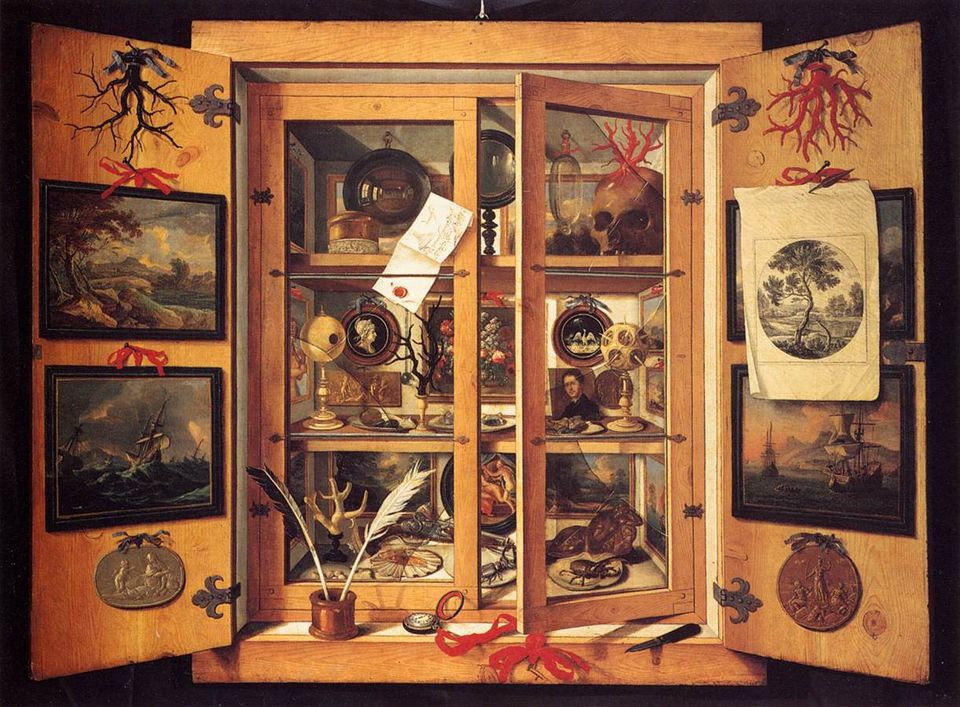

The Heat Death Cabinet of Curiosity is a handsome piece of furniture: tall, made of rich brown wood, each drawer and door capped with a polished silver handle.

It’s an elegant old thing. Perhaps it once stood in an old-fashioned library, or the salon of a rich and eccentric collector. Unlike the complex, careful educational arrangements of modern natural history museums — its natural descendents — it is a ramshackle confusion of strange odds and ends. Open one drawer and you might find a fossil; another, a few jars of preserved animals; still another, a collection of potshards. Anything, in fact, that might conceivably fit in a wood frame.

Many such cabinets have existed in our world. But this is not one of them. This piece you’re picturing is a conceptual cabinet. And that’s good: as a conceptual construction, it is capable of containing anything, so long as it is — or provokes — a curiosity.

Asher here. Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that never needs an excuse to show you something cool. First, some updates and announcements. I’ve been extremely busy finishing up an accidental novella, as well as the usual gamut of work for hire stuff, including a fun story about Texas cave paleontology that you’ll see more of in due course.

Saul, meanwhile, has been juggling some changes in his job and the purchase of an entirely new house. He’s had a busy time at The Hill recently, covering some of the basic questions around the massive East Palestine train chemical spill and the drama around Austin’s recent ice storm and power outages caused by falling tree branches. (One wag dubbed the event — which led to many people in the city losing power for days on end — ‘Arbor-geddon.’) Urban canopies are an important part of climate change adaptation for both ecological and heat-management reasons, but there are trade-offs to consider, as Saul notes.

One of the impacts of Arbor-geddon, incidentally, is that it proved the final nail in the coffin for now-ex city manager Spencer Cronk, who was unceremoniously fired by city council. (After, it must be noted, of what must have been a wonder of a group venting session in closed chambers.)

But now to our main business. Saul and I both write about science and natural history stories as part of our day jobs — he for The Hill, I for whoever will have me — and as part of that, we’re hooked into the wire of paper press releases that most people who aren’t science journalists don’t see. A lot of those papers are quite interesting! But there are far, far too many of them for any one outlet to cover.

One of the things Saul and I have talked about doing for a while, therefore, is a science digest of whatever studies came out in the last few weeks that we thought were neat. We could just list them, but honestly, where’s the fun in that? Hence, the Cabinet of Curiosity: each month, we’ll pull open a couple of drawers and see what’s inside.

It’s Heat Death. Stay with us.

THREE DRAWERS FROM THE CABINET OF CURIOSITY

DRAWER ONE: AN APE’S HAND, GESTURING WILDLY, BUT WITH INTENTION

The drawer slides open. The long hand of a chimpanzee reaches up out of the wood, moving as it rises out of idea space. Unlike the famous Koko, it is not signing via American sign language. Nonetheless, some part of you detects a sort of meaning in the gesture. A beckoning, perhaps, or a dismissal.

Great ape gestures served as some of the earliest scientifically-accepted evidence for intentional communication systems outside of human languages, and has consistently been a popular area of work. Around 80 hand signals have been identified from non-human apes. 52 of them, interestingly enough, seem to be present in very young human infants, which suggests that some of our own gestural language and sign repertoire goes back quite a considerable way. About a month ago, researchers publishing in PLOS ONE decided to try and test this, and found that humans still have some understanding of the gestures made by other great apes, even though we no longer actually use them ourselves.

The scientists in question — a team from the University of Saint Andrews in Scotland — asked participants to play an online game, where they washed 20 short videos of ape gestures, and were asked to pick from four possible meanings for each. The players performed quite a bit better than simple chance, correctly interpreting the meaning of chimpanzee and bonobo gestures over 50% of the time. Not fluent, in other words, but pretty good! About like listening to another indo-european language and being able to pick out a few similar sounds and cognates. (Did you know, incidentally, that the words suffer, ferret, euphoria and ferrous all come from the same proto- Indo-European root, bher, as in “bear” — that is “to carry?”)

The upshot is that while we don’t use these gestures anymore, we seem to have retained at least some understanding of the old communication system. Though, as the authors point out, it’s possible that humans and great apes are just able to piece together meaningful signals because we’re both smart, live in similar social contexts, and use the same equipment.

If you want to try your hand — as it were—at the game yourself, you can do so right here.

The ape’s hand gestures at you to close the drawer.

DRAWER TWO: VIRUS EATERS

A vial of pond water lies on the velvet bottom of the drawer, alongside a powerful conceptual microscope. You pick it up and slide it beneath the lens, toggling back and forth until the image comes into focus, showing you a swimming world of squirmy, single-celled organisms pursuing their mindless goals in their miniature world. Dial the magnification up — so high that the microfauna seem like a macrofauna by comparison —and you’ll find the floating bundles of reproducing unlife that we call viruses.

Small single-celled organisms living in pond water tend to consume virus particles while foraging for prey. Researchers had generally assumed that was largely by accident: protists, after all, don’t seem like the most discriminating or careful eaters. And surely, surely, those viruses weren’t providing any real nutrition. But surprise! In a study that came out last month in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, a research team from the University of Nebraska put protists in water samples with only chloroviruses to eat. Instead of dying off, the protists in the pond water — Halteria and Paramecium bursaria, if we’re formal — quite happily devoured them, growing and reproducing as they did so.

This is interesting for a couple of reasons. First, there’s the pure novelty of single-celled critters actively devouring viruses. But viruses also play an interesting ecological role in a given environment, often by killing things, which sends pulses of nutrients back out into the wider ecosystem as the dead rot and are reprocessed. This study suggests that energy from viruses themselves is probably moving up through aquatic food webs, and likely in a very substantial way: protists make up a considerable amount of earth’s biomass, and viral particles are absolutely everywhere in most aquatic environments.

The discovery suggests that there’s been a huge gap in our understanding of how watery ecosystems work. And it points at another intriguing possibility: have the actions of hunting microbes been exerting some evolutionary pressure on the viruses themselves?

Let’s leave the miniature hunters to their grisly work. You put the vial and the microscope back in the drawer, and shove it closed.

DRAWER THREE: AN URBAN ANOLE

He springs out of the drawer as soon as you pull it open, stunting on you as he paced back and forth across the wood, his red dewlap flicking out in insolent challenge. As you step back in alarm, he takes that opportunity to scurry out of the cabinet and out the window. He’s gone, buddy. He’s in the wind. He’s out there on the mean streets of the city — an environment that he and his cousins are specifically evolving to fit.

We don’t always think about them this way, but cities are a particular variety of tricky habitat. All the concrete and asphalt creates “heat islands” of higher ambient temperature, there’s generally less vegetation around, and available habitat is generally splintered by roads, cars, and housing. But there are also oases and new sorts of habitat opportunities, ones that enterprising critters can take advantage of. (Consider: house and tokay geckos are ubiquitous on many buildings in Indonesian cities, as the human invention of the lightbulb draws in an endless buffet of tasty night insects. Live any place for long enough, and you start changing to fit it: Researchers studying evolutionary changes in urban species have found that some populations, for example, shift their metabolisms toward new diets or develop increased tolerance of heat.

A recent PNAS study found that Anolis cristatellus lizards in Puerto Rico are no exception. The ones living in cities like San Juan, Arecibo, and Mayagüez have all independently evolved a set of urban traits: larger toe pads with more specialized scales, allowing them to cling to smooth surfaces like walls and glass, and longer limbs that help them sprint across open urban areas. The team also found genetic changes relating to the lizards’ immune systems and metabolism, which is a bit tougher to parse, but may have something to do with the fact that urban lizards tend to get injured more often and carry a higher load of parasites, as well as occasionally eating human food.

“Understanding how animals adapt to urban environments can help us focus our conservation efforts on the species that need it the most, and even build urban environments in ways that maintain all species,” said lead study author Kristin Winchell. In the meantime, anoles are going to keep hacking it out there on their own.

A SET OF VERY SMALL DRAWERS, EACH CONTAINING AN INTERESTING LINK

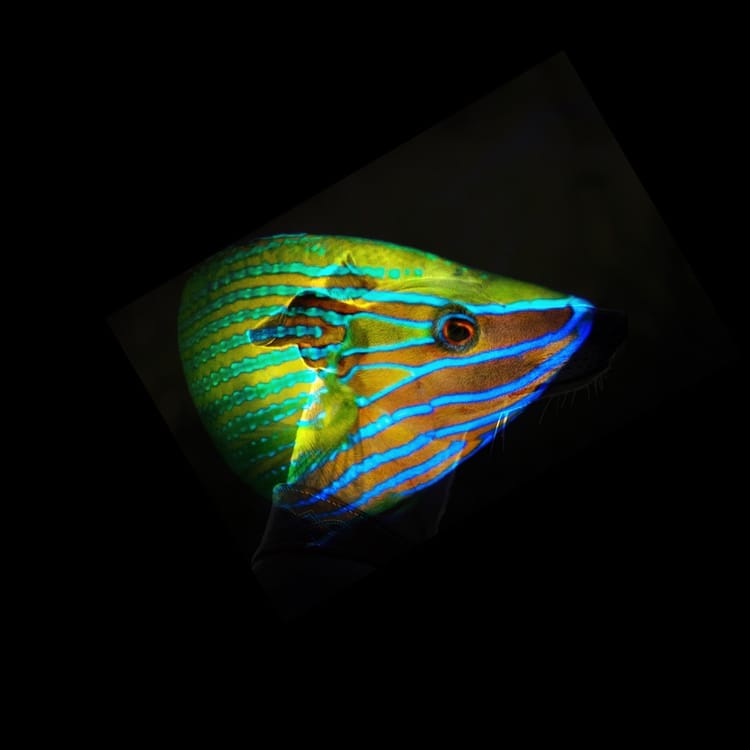

— A good tweet about why wild beta fish species look a lot more handsome than domesticated ones

— A cat passport from the mid-20th century

— An interesting reconstruction of the famed mongolian wolf-eagle

— A book review about how we’ve all gotten too enlightened

That’s all for Heat Death today, everybody. If you’d like to send ideas for the Cabinet of Curiosity — or general feedback — you can always reach us at elbeinbrothers@gmail.com.

If you like our work, why not grab a paid subscription and help keep us going? Doing so will get you access to our growing Discord server, which is a bit like a perpetual Cabinet of Curiosities, if you really think about it.

Member discussion