Return of the Cabinet of Curiosity

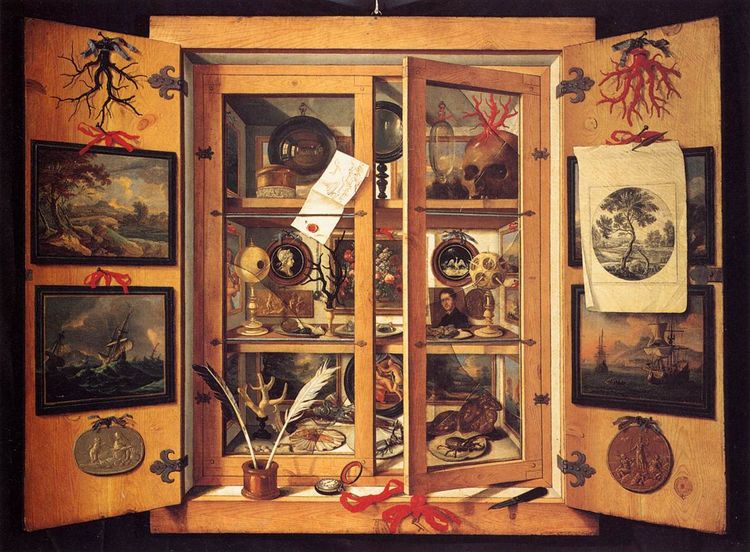

In a long forgotten room in a rarely visited mansion, which lies a shadowy street in a once magnificent part of town, you will find the Cabinet.

It is tall and handsome, made of hardwood carved from the kinds of trees now under international protection; the silver handles that promise entry to it's cupboards a defiant contrast to the dust and gloom.

The Cabinet is not a museum, and if it could talk — perhaps it can — it would tell you so. It is innocent of any curator's guiding hand, spared any authoritative marginalia to help make larger sense out of what is inside. Many such cabinets have existed in our world. But this is not one of them. This piece you’re picturing is a conceptual cabinet. And that’s good: as a conceptual construction, it is capable of containing anything, so long as it is — or provokes — a curiosity.

Look within, that winking silver seems to say. Draw what inferences you like. But they will be nothing but that: bits of supposition, cast before an uncaring world too big and strange to be whelmed by any comforting theory.

Instead, then, what the Cabinet offers is something odder, and in some ways more gratifying: concentrated bits of uncomfort — like piquant bits of hot pepper or horseradish for the gray expanse of life. Bits of the uncanny assembled by a collector far more idiosyncratic than any highly-credentialed museum curator.

And now, wouldn't you know it — your hand, of its own will, is reaching for those handles.

But wait! First, some news.

WHAT HAVE THOSE ELBEIN BOYS BEEN DOING?

Saul had a busy January, much of it devoted to science writing. He covered the surprising evolutionary benefits of bisexuality.

But much of the month was devoted to more somber fair, and in particular the state of American drinking water. He covered the grim trajectory of American groundwater (and the states where it’s going fastest), as well as why bottled water is a potentially dangerous substitute: it’s contaminated with plastics the size of viruses. That story inspired a for-the-record response from the bottled water industry’s main trade group, which argued that the study picks on them unfairly, because (as we covered) nanoplastics are simply everywhere — including virtually all American meat and vegetable proteins. Also, plastic pollution may cost the country a quarter trillion dollars in added healthcare costs per year — which scientists argued was probably a low estimate.

Then there were the Big Stories that have locked down our political discourse: the gas export pause and Texas’ continued series of provocations over the so-called border crisis. On the first, he wrote about the ‘revolt’ of Democrats pushing Biden to cut gas exports, and how Biden’s decision to ultimately do so meant standing up to the pro-gas legacy of his former boss, President Obama.

And on the border, he went deep on how the federal government created the immigration crisis that now bedevils it — and did a close read of the punitive new border policy that Republican hardliners have threatened for months to shut down the government over.

In lighter fare, there was, as always, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, who on the day he was set to be forced to testify in court — an outcome he was only saved from by Trump’s intervention — made the head-scratching announcement he was going after five Texas cities that had decriminalized weed. And finally, so you don’t have to: he read the gripping, stomach-churning report of what went wrong during the 2022 school shooting debacle in Uvalde, Texas.

Asher likewise began the year with a series of science pieces, including three back-to-back pieces about his favorite subject: dinosaurs.

January saw two salvos in the ongoing Tyrannosaurus wars, fought over the question of whether every fossil named T.rex is, in fact, T.rex. The first centers on the bedeviling Nanotyrannus, an animal that is either a pygmy tyrant or (more likely) teenaged Tyrannosaurus, but that a certain faction of researchers absolutely refuses to let go of. The second centers on the first attempt to name a new Tyrannosaurus species not to be immediately laughed out of the room: meet Tyrannosaurus mcraeensis, which is quite possibly the direct ancestor of T.rex.

He also covered a fun study where some researchers scared the bejeezus out of wild grasshoppers with a robotic dinosaur, as part of an interesting but probably unprovable argument that insect-flushing behaviors were vital to the development of wings, and thus flight.

Finally, he wrote about a study that investigated how plants “see” with their whole bodies, in an absolutely gorgeously-produced piece for Quanta Magazine, and tackled the question of why birds have such skinny little legs for Scientific American.

It’s a bounty of interesting coverage — and we have more for you now, as we dive back into the Cabinet of Curiosities. It’s Heat Death, everybody. Stay with us.

DRAWER ONE: A MINIATURE ECOSYSTEM ENGINEER

The drawer slides open. Inside, you find a small test tube, complete with a big-headed ant in the act of dismembering a smaller acacia ant. Its antennae wave, mandibles clacking as it goes about is grisly work. It’s not big, or particularly terrifying — certainly nothing as dramatic as the irradiated ants of pulp fiction, or the flying columns of army ants found in equatorial jungles.

But as Ray Bradbury could tell you, small actions can ripple out in big ways. The big-headed ants are invasive in East Africa, and — like most of their kind — don’t play well with other ant species. As a result, they’re in a constant state of war with the native acacia ants. The native ants, in turn, protect thorny acacia trees from grazing herbivores in exchange for housing: elephants, giraffes and other herbivores that try it tend to end up stung as well as hungry. But while they can stand up to mammals many times their size, the big-headed ants represent a more formidable threat: where they go, acacia ants are often pushed out.

According to an innovative new study, that shift has major implications for the shape of the ecosystem, down to reshaping the diets of its primary predators. It goes like this: when the acacia ants are pushed out by their big-headed rivals, their trees are left vulnerable to overgrazing by elephants, whose browsing — and associated wear and tear — went up as much as seven times in big-head ant territory. That meant more dead acacia trees and a much more open landscape.

And that meant less cover for lions, who use acacia trees as blinds to stalk their preferred prey, zebra. In order to get by, the lions therefore had to start targeting a significantly more dangerous prey item: the african buffalo. It’s a fairly dramatic shift in diet: over a 17 year period, zebra kills by lions went from 67% to 42%, while buffalo hunts went from zero to 42%. All of which can be directly traced to the war between two specific ants.

The big-headed ant finishes dismembering the acacia ant and begins casting about the test tube, as if in search of more worlds — and ecosystems — to conquer. Hurriedly, you put the test tube down and close the drawer.

DRAWER TWO: AN UNEXPECTED YOUTH

A large drawer near the bottom of the cabinet is made of glass: it is almost the length of a human being, and almost unshiftably heavy with greenish liquid. When you pull it out, it smells like the sea, so you dip your finger in to taste for salt — and feel sudden, stinging pain. Your top knuckle is gone, and your blood streams into the water, visibly exciting the drawer-tank’s occupant: a five foot long pure white fish with a characteristic pointed dorsal fin.

In your shock, you realize that it is a baby shark — or, specifically, a newborn white shark, a creature first seen in the wild by scientists in January, when wildlife filmmaker Philip Gaunt videotaped a new kind of shark pup swimming near Santa Barbara, California.

“We enlarged the images, put them in slow motion, and realized the white layer was being shed from the body as it was swimming,” doctoral student Philip Sternes said later. “I believe it was a newborn white shark shedding its embryonic layer.”

If so, it helps shed light on a dark corner of marine biology.

“Where white sharks give birth is one of the holy grails of shark science. No one has ever been able to pinpoint where they are born, nor has anyone seen a newborn baby shark alive,” Gauna said. “There have been dead white sharks found inside deceased pregnant mothers. But nothing like this.”

White sharks give birth to live young, which snack on their mothers’ unfertilized eggs while growing inside them — as well as nutrient-rich fluids secreted by the uterus. This “milk” was part of what the baby shark was shedding, Sternes contended.

With a knuckle gone from your finger, you might find it hard to care about this. But this is a conceptual Cabinet. After you shoulder the drawer closed, you look down to find your finger whole — the wound is gone, as though it was never there at all. But as it’s not a real wound, it also may not have been a real baby shark. Sternes and Gauna think that the shark — who they say was just a day old — might have been a shark with a skin condition.

But “if that is what we saw, then that too is monumental because no such condition has ever been reported for these sharks,” Gauna said.

DRAWER THREE: A SIDENECK TURTLE AND THE SHELL OF A VANISHED GIANT

The drawer pulls out, and out, and out. Inside, a snake-necked turtle sits atop a turtle shell over seven feet long and almost as wide. The turtle blinks wetly at you, peering up coyly from the rim of its shell. Unlike most North American turtles, which pull their necks back entirely inside their armored casing, side-necks use an older method: folding their neck sideways. It’s only the size of a pond-slider. But as you can see, some of its ancestors got considerably larger.

This is a bit of a puzzle, because a long-standing “rule” of biology — or at least a guideline — is that animal lineages tend to evolve larger body-sizes over time. The 19-century paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope pointed out variations on the pattern: horses moving from dog-sized animals to large grazers, dinosaurs growing from small hunters and browsers to enormous sizes, and mammals writ large expanding after the Cretaceous.

It’s a nice theory. But it doesn’t fit the facts. Fossil evidence suggests that while size does increase in some groups, others have shrunk over time, from island lizards to the horses of Ice-Age Alaska. And new research suggests that those growth and shrinking spells occur alongside changes on the landscape, said scientist Shovonlal Roy: “Changes in ecological factors help explain why fossil records shows such confusing mixes of size evolution patterns, with some lineages shrinking over time and others growing.”

Roy and his colleagues ran models that helped clarify the processes at play. In some cases — when species competition was centered around relative body size rather than specific niches, as in some marine invertebrates — lineages gradually got larger.

In other cases, size increase was cyclical: the largest animals in a given family would evolve, reign, and go extinct, to be replaced by other species that evolved even larger bodies. That’s the process that produced multiple lineages of giant dinosaurs, a relay race of families that carried on right up to the modern day: birds have continually evolved enormous size — as enormous as birds can get, anyway — up to a few thousand years ago. (The flying theropod body plan has its limits.)

But sometimes — in times and places with extreme competition between different species for food and shelter, animal sizes tended to get smaller, as species spread out and adapted to scarcer resources and more competitors. It’s happened in those Alaskan horses, in some bony fish, and island-stranded mammals.

It’s also happened for side-necked turtles. The giant shell in the cabinet belongs to Stupendemys: a 5 million year old south American side-neck that’s possibly the largest freshwater turtle to have ever exist. No turtle in the family — no turtle period — gets that big today.

The snake-necked turtle’s claws scratch on the shell as it backs away from you, letting out a warning hiss. You shoulder the drawer closed in search of something smaller — something that’s stayed small.

DRAWER FOUR: A REPRODUCTIVE INFECTION (NOT THAT KIND)

A small pigeonhole at the top of the Cabinet opens to reveal clear liquid in a glass vial, which — because this is a conceptual cabinet — suddenly magnifies the nano-scale material within: a string of the letters A, T, C and G. The strings are bits of DNA, and not just any DNA: viral DNA, pulled from the genomes of a human very much like yourself. (Or perhaps yours. Yes, yours. This is a spooky cabinet.)

These fragments are ancient hitchhikers — injected and integrated into the genes of the early animals at the core of the Cambrian explosion, the vast radiation of new life half a billion years ago, in the aftermath of the Great Dying.

They are surprisingly numerous, these hitchhikers: they make up 8 - 10 percent of your DNA, and they had long been thought to be “junk:” bits of repeating code blindly passed on for eons despite a lack of use or function.

But a team of Spanish scientists discovered this month that these bits of viral DNA are far from junk: in fact, they are essential to human development, and may have helped drive the Cambrian explosion itself.

In the hours after an egg is fertilized, the scientists discovered, these viruses are essential in helping the early embryo divide from two cells to four — allowing it to begin the process of differentiation that leads to, well, you.

"Intuitively, it was thought that having viruses in the genome could not be good,” researcher Sergio de la Rosa said.

“However, in recent years we are starting to realize that these retroviruses, which have co-evolved with us over millions of years, have important functions, such as regulating other genes.”

A SET OF VERY SMALL DRAWERS, EACH CONTAINING AN INTERESTING LINK

— A smattering of cryptid-related ephemera

— A folk-horror murder victim from 5000 years ago

— A pair of gay anteaters

That’s all for Heat Death today, everybody. If you’d like to send ideas for the Cabinet of Curiosity — or general feedback — you can always reach us at elbeinbrothers@gmail.com.

If you'd like to support the newsletter, you can grab a paid membership for just 5$ a month. Or just keep enjoying our free offerings by signing up right here.

Member discussion