Orc is Man To Orc

The orcs are on the march. Up they come from mine and dungeon, the sunlight glinting on their crude blades. They come hideous and deformed, bent of limb and snarling of mouth, their skin scurvy-yellow, corpse-gray or bright rot-green. They come singing deep-throated, piratic and (let’s be honest) eminently hummable songs.

They are warlike. They are cruel. But more than anything, they’re familiar. You know an orc when you see one, and you know what it signifies: at best, the noble, misguided savages. At worst, evil things made to fight and die in the service of darkness.

These are the Bad Guys — as pure and easy a distillation of evil as Western literature has given us. They are craven, cowardly and (probably) cannibalistic sponges made to soak up all the righteous violence our heroes are shortly to mete out in the name of saving the world. Watching an orc walk on screen is something like the appearance of American Indians in Golden Age westerns, or a Nazi in a modern war movie — a readymade package of associations that tells you who they are, what they stand for and what can fairly be done with them.

Needless to say, all of this rings a bit uncomfortably in this year of our lord 2022. There’s little in the above description of an orc that you could not have read, with minor variations but little irony, being offered in British and American newspapers at any point between 1600 and 1940, to justify campaigns against the inhabitants of Africa, Asia and the Americas that were often frankly genocidal.

"These are the vilest miscreants of the savage race, and must ever remain the pirates of the Missouri,” William Clark of the Lewis and Clark expedition wrote back home of the Teton Sioux.

This group — who call themselves the Thítȟuŋwaŋ or Lakota — dominated the rich bottomlands and trade routes of the upper Missouri River as part of a loose tribal republic called the Council of the Seven Fires. Over the near-century of grueling warfare that followed, American soldiers and militia broke apart the Council’s eastern peoples and seized its heartland in the Dakotas in a wave of broken treaties.

As they did so, many Americans turned to such supposedly orcish tendencies to justify their country’s strangulation and digestion of another sovereign republic

But this leads to a less obvious point: that apparent ‘orcishness’ is both in the eye of the beholder and — often — a response conditioned by the past. Reading Clark’s diary, it is hard to shake the thought that the Lakota were “pirates” of the Missouri to Clark simply because they did not bow to European authority. They were proud, boastful and above all independent — willing to demand or take gifts from Europeans who crossed their territory.

And so Clark offered a frankly imperial solution: the Lakota would remain pirates and miscreants “until such measures are pursued, by our government, as will make them feel a dependence on its will for their supply of merchandise."

In other words, until their independence was broken — as it would be, through precisely such tactics of siege, over the next century — orcs they would remain.

Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter read from Mount Gundabad to the Mines of Moria, or wherever you can find a human able to translate from Common. (We tried a Quenya edition, but the Elves can’t keep up with periodicals any more frequent than once a decade.)

Saul has been reporting for The Hill on the many faces of the American West's water crisis — with a particular focus on why Texas' independent cattle raisers are worrying about extinction, and why the state's cities are concerned about running out of water.

Asher has been busy driving the backroads of Texas after snakes, as part of a forthcoming Texas Highways story on field herpetology, and writing in The Daily Beast about the nationalist (and fully deranged) Marvel superhero Sabra.

Today we’re going to take a deep dive into the darker corners of the legendarium that inspired both The Rings of Power — Amazon Prime’s recent $1 billion attempt to bring mass culture back to the small screen — as well as much of the set of structures and conventions that we generally refer to as fantasy.

In doing so, we’re going to ask a question with some unsettling resonances for Anglo-American history and culture: not “what is an orc,” but why is an orc? What does it take—narratively and materially—to create an entire race of enemies?

This is Heat Death. Stay with us.

On The Problem of Orcs

Asher here. Let us return to the question of orcs, and how they came to be.

In 1954, the first edition of Lord of the Rings— an epic fantasy novel by Oxford scholar, committed Catholic and Great War veteran J.R.R Tolkien—debuted to middling reviews and reasonable commercial success. The work was a darker sequel to his successful children’s novel The Hobbit, and an expression of a more deeply esoteric project: an attempt to fashion a distinctly Old English mythology, complete with its own invented languages, histories, and peoples.

This project was not the sort of thing you’d think would take the world by storm. But over the next few decades, Tolkien’s works set in Middle Earth—particularly Lord of the Rings—achieved tremendous commercial success and became a touchstone in 1960s counterculture. By the 1980s, they had utterly reshaped modern fantasy, spawning waves of imitators from Robert Jordan's Wheel of Time to Dungeons and Dragons. They became more popular still in the early 2000s, after an early-career director named Peter Jackson sweet-talked Warner Brothers into letting him adapt the saga into a blockbuster trilogy of films, which spawned its own wave of video games and other ancillary materials. Today, Lord of the Rings remains a tower on the landscape of modern fantasy. You don’t have to walk toward it, but it’s always there on the horizon, and its shadow is long.

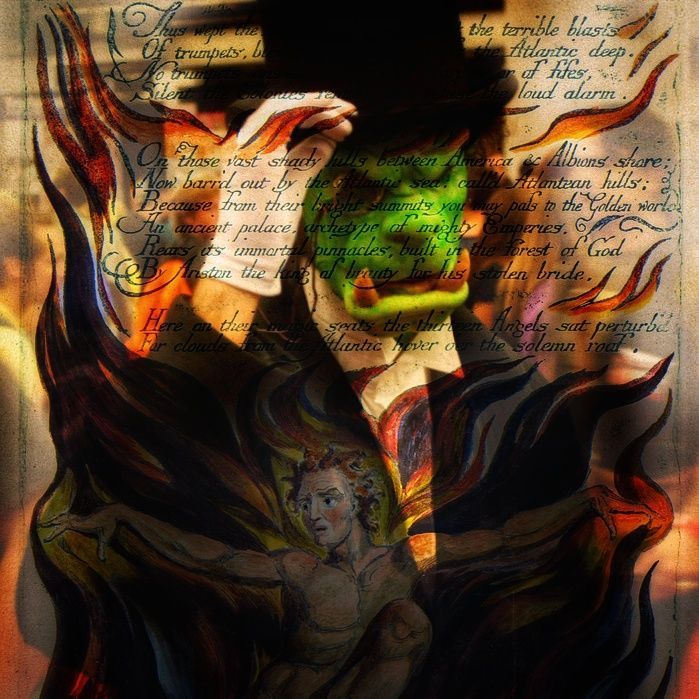

And what dwells in that shadow? Against his humble hobbits, wise elves and flawed-yet-noble men and dwarves—and crucially, against their intricately constructed languages—Tolkien needed to create an enemy people. Being a scholar of old English, he plucked a rather obscure word out of the epic poem Beowulf: ‘orc.’

Orc has deep but rather amorphous roots in English, seemingly derived from the latin Orcus (a synonym for Hades). A 10th century dictionary glosses it as “goblin, specter, or hell-devil;” the word orcneas turns up in the epic Beowulf amid a list of the evil peoples born from Cain’s blood, and means something in the key of “evil spirits” or “devil corpse.” (You might also broadly translate it as adversary, which, of course, was precisely what Tolkien was looking for.)

Tolkien’s orcs—which he also sometimes called goblins—are fanged, bow-legged and long-armed humanoids, queasily described in a private letter to a potential film producer as “squat, broad, flat-nosed, sallow-skinned, with wide mouths and slant eyes: in fact degraded and repulsive versions of the (to Europeans) least lovely Mongol-types." In their appearances throughout The Hobbit, Lord of the Rings, and posthumously published works like The Silmarillion, they are a cruel, shambling and predatory people, fearful of the sunlight, existing primarily as foot-soldiers of the vast and evil powers that created them.

From this literary birthing pit, the orc went forth. Novelists like Robert Jordan adapted Tolkien’s orcs as stock characters, changing the name ("Trollocs," in Jordan's case) but keeping the origin and narrative function. Gary Gygax, who never met a Tolkien idea he wouldn’t steal, shoved dark-skinned Tolkienian orcs directly into his 1974 table-top game Dungeons and Dragons. (D&D’s player handbook describes them thusly: “savage humanoids with stooped postures, piggish faces, and prominent teeth that resemble tusks. They gather in tribes that satisfy their bloodlust by slaying any humanoids that stand against them.”) Orcs—now green-skinned, boar-tusked and enormous—appeared in the high-camp fantasy wargame Warhammer, which was, in turn, lifted by the videogame studio Blizzard to make the hit strategy and RPG gaming franchise Warcraft.

Some writers pushed back on all this, of course. Others—reacting to a growing sense that having an entire species of innately evil, often dark-skinned humanoids might have some ugly racial overtones—sought to refashion them as noble savages. But even in such attempts to evoke sympathy for the orc, the notion of them as inherently adversarial entities has largely stuck. “In most fantasy settings in which I’ve seen orcs appear, they are fit only for one thing: to be mowed down, usually on sight and sans negotiation, by Our Heroes,” fantasy novelist N.K Jemisin wrote in a post describing her distaste for orcs. “Orcs are human beings who can be slaughtered without conscience or apology…Creatures that look like people, but aren’t really. Kinda-sorta-people, who aren’t worthy of even the most basic moral considerations, like the right to exist.” Such a creation is inherently poisonous, Jemisin points out, no matter how you try to revise it.

Someone who might have agreed with her: Tolkien himself. Because as it turns out, the Oxford don was well aware of the problems with the orcs he’d fashioned—a people who, for all their status as disposable enemies, are rather more complicated then later writers tend to give him credit for.

The most important thing about orcs in Tolkien's legendarium is that they aren't primarily portrayed as sentient beings, even evil ones. They are portrayed as weapons.

In the Silmarilllion—a posthumously collected work of Middle Earth mythology and history—orcs are fashioned by an entity of primal evil, the rebel angel Morgoth, in mockery of God’s creation of elves and men. Quite how this spiteful spirit made them is textually a mystery, although Tolkien offers a possible explanation: that the devil captured early elves and warped them through torture and dark magic into a slave race of monsters. (The later Peter Jackson films treat this as a fact: Tolkien’s writing is far more equivocal, and he changed his mind about it quite a few times without arriving at an answer that satisfied him.)

For hundreds of thousands of years (per Tolkien), Morgoth and his successor Sauron sent armies of orcs against elvish and human societies. When beaten, the scattered orcs retreated to underground strongholds, licked their wounds, and bred their numbers back up until the next time a powerful warlord came along to pressgang them into service. By the time of Lord of the Rings, therefore, the free peoples of Middle Earth regard orcs as agents of the enemy, inherently wicked and deserving of no consideration whatsoever. To them, orcs simply have no meaning outside of the context of war. They are never at peace, and are always a source of either active or potential destruction. They are a perfectly dehumanized enemy.

But Tolkien’s orcs do have their own stuff going on. In both The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, they speak and think—if often in obscene or crude language—are cunning inventors of weapons, and hold a bone-deep hatred of elves, men, and the dark spirits that compel them into service. As Tolkien scholar Robert Talley Jr. notes in an excellent paper, orcs maintain different communities and societies of their own, with different motives and allegiances; are motivated by vengeance rather than innate malice in their feuds with dwarves and elves; and are capable of great personal bravery in avenging fallen captains.

They also bitch and moan about the obnoxiousness of military life as much as any human soldier. Consider the following exchange between two Mordor orc soldiers in The Two Towers, as they quietly wonder whether their superiors are competent and how any fuckups are likely to rebound onto them.

“Those Nazgûl give me the creeps. And they skin the body off you as soon as look at you, and leave you all cold in the dark on the other side. But [Sauron] likes 'em; they're His favorites nowadays, so it's no use grumbling. I tell you, it's no game serving down in the city.'

'You should try being up here with Shelob for company,' said Shagrat.

'I'd like to try somewhere where there's none of 'em. But the war's on now, and when that's over things may be easier.'

'It's going well, they say.'

'They would.' grunted Gorbag. 'We'll see. But anyway, if it does go well, there should be a lot more room. What d'you say? - if we get a chance, you and me'll slip off and set up somewhere on our own with a few trusty lads, somewhere where there's good loot nice and handy, and no big bosses.'

'Ah!' said Shagrat. 'Like old times.'

Letters reveal that Tolkien’s conception of Orcs is fundamentally human, albeit humans that represent the worst sort of infantryman. In one 1954 letter, in fact, Tolkien goes so far as to describe orcs as fundamentally “‘rational incarnate' creatures, though horribly corrupted, if no more so than many Men to be met today.” In another, he remarks that in real life, orcs would be present on both sides of any conflict. But Lord of the Rings, after all, is intended to be romantic fantasy in the classical sense, akin to Arthurian sagas or mythology, and in such stories “good is on one side and various modes of badness on the other. In real (exterior) life men are on both sides: which means a motley alliance of orcs, beasts, demons, plain naturally honest men, and angels.”

Yet if orcs are essentially people, then that opens up a serious can of worms. Tolkien was a devout Catholic, and while he professed himself allergic to the sorts of didactic Christian allegories produced by his friend C.S Lewis, he was deeply interested in the moral dimensions of his work. And as a Catholic, the notion of an entirely irredeemable species bothered him.

Tolkien’s dilemma was this: The world of Middle Earth, though full of various minor gods and spirits, is organized along roughly monotheistic—and thus, for Tolkien, Christian—lines, with an Creator God, angels both ethereal and fallen, and a devil. This devil could not have created orcs evil out of whole cloth, Tolkien decided, because according to his understanding of Catholicism, evil can’t truly create anything of its own: it can only pervert and ruin existing materials. Similarly, by being of the world created by God and with the tacit permission of God, orcs therefore are his children as much as anyone else’s — meaning that salvation is as possible for them as anyone else.

And if that’s true, the fact that his heroes kill them without a thought raises deeply uncomfortable questions about those heroes' own morality.

Awareness of this problem seems to have dawned on Tolkien over the course of writing Lord of the Rings. It isn’t much of an issue in The Hobbit, wherein orcs are hostile to Thorin’s dwarven band, but not a great deal more so than the fey and unpredictable wood elves or the greedy men of Laketown. Throughout Lord of the Rings, as we’ve noted, orcs are characterized as unquestionably thinking beings, having factional arguments and dreaming of the day when they can bugger off organized soldiering.

Yet Sauron’s fall at the end of Return of the King leaves the surviving orcs of his army practically witless. The implication—that they were somehow being puppeted by Sauron’s power, and without it are barely sentient—fails to square with anything that came before. It smacks of Tolkein attempting to sidestep a question that was starting to bother him.

It’s bothered plenty of other people, too. The traditional literary move in tackling the conundrum of the innately evil orc has been either to willfully ignore it—the D&D method—or to pursue a revisionary approach that treats orcs as ill-used losers demonized by the elves and hobbits who wrote the history books. (This is the tack taken by the 1999 Russian fanfiction novel The Last Ringbearer, which casts the Orcs of Mordor as participants in peaceful constitutional monarchy of science and industry, one overthrown by the aggressive and undying bigotry of the elves.)

But there’s a thornier option: to stop viewing the question of orcs as a flaw in the text, and instead to consider what their depiction might suggest about Middle Earth. To do that, you don’t need to make anything up, or change any details. You just need to start asking questions.

In the introduction of Charles Mann’s excellent 1491, he writes of the researcher Holmberg, who in the 1940s studied the Sirionó people of Bolivia. Holmberg called them “among the most culturally backward peoples of the world,” and the “quintessence” of “man in the raw state of nature.” He drew this conclusion because the Sirionó had no clothes, art, musical instruments, or sense of religion.

Later researchers discovered that Holmberg had missed a crucial point: that 95% of the Sirionó had been wiped out by smallpox epidemics, amid ongoing suppression by the Bolivian government and cattle ranchers. Far from being people in the raw state of nature, the Sirionó were refugees of a shattered people. They were a product of past circumstances; they had a history. Holmberg’s Mistake, as Mann terms it in 1491, was to assume that they did not. He took them as they were, and did not ask why they were.

That's bad enough for a researcher, but it stemmed from a deeper failure: Holmberg did not imagine that there could be a why.

Let us, then, look at Tolkien’s orc and ask why.

Question: What damage was caused by elves’ apparent belief that orcs are simply a twisted mockery of themselves, rather than (potentially) a sibling people enslaved by a power of endless and potent malice? The word “orc” in Tolkien’s Elvish literally means monster, and elves, dwarves and humans have all proceeded in the assumption that orcs cannot be treated any other way. (Certainly, if any elves made an effort to reach out diplomatically to orcs after the wars to try and normalize relations—much less integrate them into their societies—Tolkien doesn’t record it.)

Question: How much of the nature of orc society was determined by its history? In Tolkien’s legendarium, recall, enslaved orcs have been infantry in multiple ruinous conflicts, wars both cold and hot that raged continuously for hundreds of years. These wars have generally not been of the orcs’ choosing: they have acted as the exploited slave army of various dark lords.

And in the aftermath of these wars, Middle Earth’s other societies have tended to pursue policies of absolute extermination against any orcs they find: they are, after all, weapons of the great enemy. Every time orcs start emerging as a serious power, someone wades in to break them up. (One of these wars, a series of battles between dwarves and a series of underground orc settlements around the contested Mines of Moria, is described in Lord of the Rings’ appendices as a campaign of extermination so grim and pitiless that dwarf veterans afterward won’t talk about it.)

Notably, Sauron’s human vassals are integrated into peacetime at the end of Lord of the Rings: the orcs are not.

Question: How much of orc society’s tendency toward banditry and cruelty, then, is based around the fact that they have tended to live their entire lives—to spend whole generations, in fact—either under the harsh hand of military slavery, or else as hunted nomads under the constant threat of extermination? Tolkien’s orcs only live in their own lands and strongholds, and are hostile to outsiders. They speak occasionally—and bitterly—of elvish and dwarven bloodthirstiness and trickery. (Interestingly, the encounter with the Goblins in The Hobbit starts off tense but only turns markedly hostile when the dwarves are revealed to be carrying elven weaponry. “Murderers!" rages the orc chieftain. "Elf friends!”)

In fact, we never see one of the free peoples of Middle Earth take an orc alive, while orcs do regularly take prisoners and often treat them reasonably well, even if only for practical reasons. Consider also that orcs who aren’t closely affiliated with either Mordor or the wizard Saruman, such as those of Moria and the Misty Mountains, are often described as being motivated primarily by revenge over past blood feuds, generally those with dwarves. In The Two Towers, amid a custody dispute between Saruman's Uruk-Hai and Sauron’s orcs over a pair of hobbits, a northern band of orcs from the Mines of Moria expresses an utter lack of interest in the politicking: “We have come all the way from the Mines to kill, and avenge our folk. I wish to kill, and then go back north.”

This is a subtle but revealing character note: it suggests less of an innate inner malice than a long memory. The orcs, at least the free ones, see themselves — and each other — as people worthy of avenging; the orcs are at least partially motivated by an understanding of the world carved between us and them.

All of which leads to the crucial question: does it have to be this way? To what degree is Elvish—and to some extent, human and dwarven—society’s view of orcs as the eternal enemy a self-fulfilling prophecy, born of endless years of warfare, mistrust, and an inability to forget or forgive? Is it even possible for orcs to move forward when dealing with elves — who are, recall, immortal beings that have lived through multiple wars with their ancestors, and find the wartime atrocities committed by them impossible to forget? Or with enemies like dwarves, who are famously intractable when it comes to holding a grudge?

You don’t need to cast elves and dwarves as the real villains here, a la The Last Ringbearer. Rather, I think it’s possible to read this as a sign of how foundational—how deeply, terribly fundamental—these ancient hatreds are on both sides.

These questions actually fit nicely with Tolkien’s larger themes. Contrary to the popular imagination, which tends to flatten his work into simple stories of light and dark, Tolkien’s stories are about the problem of evil, and about the ways that warfare and conflict—even necessary wars waged against primal evil—inevitably change and diminish societies that enter into them.

Far from good inevitably triumphing, the entire arc of Tolkien’s legends are a litany of failure, destruction, and encroaching twilight. By the time of Lord of the Rings, Middle Earth is a setting that has seen millennia upon millennia of conflict, sometimes on a scale that beggars belief. Those struggles have left their scars: whole civilizations and lineages passed into dust and shadow, the spectral byproducts of their conflicts littering old battlefields like so much unexploded ordnance, the grandeur of the past a hazily remembered myth. The survivors—particularly the few semi-immortal souls kicking around who remember the fleeting glory days—live amid the ruins, and a deep sense of rotting, ossified history that hangs inescapably over everything. And everyone is, in their own way, imperfectly navigating the spreading, lingering cracks that fundamental evil left in creation.

The peoples of Middle Earth treating orc-kind as the adversary is thus another lingering tragedy among many. This is the brutal irony in Tolkien’s text, whether he intended it or not. Morgoth fashioned himself a race of enslaved beings to mock the elves, supposedly the wisest of all peoples. In this, he succeeded: the proof is in what happened next. He set these slaves against the other peoples of the world, and none of them—not the elves, wise and fair and unchanging; not the brave, vengeful dwarves who might have shared the dark; not even corruptible, fallible men—ever bothered to ask if those souls could be saved.

Instead they all accepted a poisoned and seductive gift: an eternal enemy, to be killed without compunction or mercy. An unpeople they could fight forever — one that could inspire acts of evil so vast that wise men stroke their chins and call them “good.”

Or, to put it another way—

The elves remember. They are timeless people, and so time has not stolen it from them—those who were there at the sack of Gondolin and Beleriand, who can still recall the bitter taste of blood in their mouths, the shouts and screams in the black speech. The lines shattering, the melee, the muck of the last assault upon Mordor, where Gil-Galad fell at the enemy’s hand. The unimaginable horror of watching eternal life cut short. Every moment is etched into them, crystalline and sharp. Not dulled but the passage of years, but honed.

And so no elf will suffer an orc to live. This is not vengeance, as humans understand it—not anymore. It is not vengeance to live for millennia in the memory of horror, fear, and hate, to feel it anew every time they spy the twisted forms, which—their learned ones say—were bred in mockery of them by the devil. It is all still too fresh, even now, thousands of years later, amid the wreckage of the past, in a world that might have been a paradise. For elves, this is simply fact: the only good orc is a dead orc.

The dwarves remember. The details of past ages are lost to them: they do not live as long as elves. But they remember how the orcs came creeping like vermin into their lost halls, after the dread thing in the depths drove them out. They remember the insult Azog the orc chieftain paid their exile king when he tried to return—decapitation and a pouch of old coins thrown to his companion, as if to a beggar. An unbearable insult to a proud and grieving people. They remember the war that followed, inch by bloody inch through cave and mine amid the Misty Mountains, a war so terrible that no veteran ever spoke of what he saw, and young dwarf-men grew up amid elders made hard and cruel as stone.

And so no dwarf will suffer an orc to live. The dwarves pursue the vendetta as relentlessly as they moil for iron and gold in the depths. Nothing else to be said about it. The only good orc is a dead orc.

But the orcs remember, too. They don’t live as long as elves, dwarves, or even as long as men. The wars of past ages are distant myth; no living orc stood before the terror Gal-adriel at the height of her ferocity and rage, saw the blood of their compatriots dripping from her sword.

Yet they grow up knowing that the she-elf waits in her redwood halls, her hawk face serene, thirsting for the blood of orc-folk; that she and her forever people will forever hate them, will catch and kill them if they can. They grow up hearing of the horrific wars with the longbeards, fought in shafts and black galleries beneath the Misty Mountains, and how the dwarves high-handedly sought to push orc-kind from halls they themselves—weak! cowardly!—abandoned to flame and shadow. The horselord brigands hunt them for sport; the men of the White-Tree-City for glory. Assassins and thieves come into their strongholds and kill their chiefs, and those who ride out to avenge them die.

They do not know where they come from; they do not care. The world hunts and hates them; they hunt and hate right back. Anything they want must be taken by the sword. To survive, be fucking tough and fucking quick. If you aren’t the meanest cunt around, find yourself a meaner one to stand behind: war-captain, wayward wizard, black lord of fathomless hate.

What else is there for Morgoth’s people? What else can there ever be, before the memory of the elves?

You've been reading Heat Death. If you'd like to support the newsletter, you can grab a paid membership for just 5$ a month, or keep enjoying our free offerings by signing up right here.

That's all for this week. Take us out, lads.

Member discussion