The Paleontologist's Scrapbook

To be interested in extinct animals is to be interested – almost inevitably – in popular culture.

As European and American natural historians started describing the bones of vanished mammals, strange reptiles, and other antidiluvian oddities, many of those discoveries were processed by the great and gnashing jaws of that other – now sadly endangered – predator: the press. It was a symbiotic relationship. Researchers craved recognition of their work, in part to advance the new scientific ideas, and in part with an eye on fundraising and status; journalists hungry for sensational stories and good copy knew that tales of vanished monsters went down well with the reading public. (They still do.)

But as awareness of prehistoric beasts filtered out, they began popping up in other places. There were popular novels and animated projects, of course. But the beasts of distant epochs also began showing up in other places: poems published in magazines or circulated among scientists, humor columns, and – always and inevitably – newspaper cartoons. Many of which lasted only as long as the individual paper or issue, and found their way inevitably into the trash, never to be seen again.

Unless, of course, someone were to save such things from the scrapheap of history. Perhaps by cutting them out and sticking them in a book.

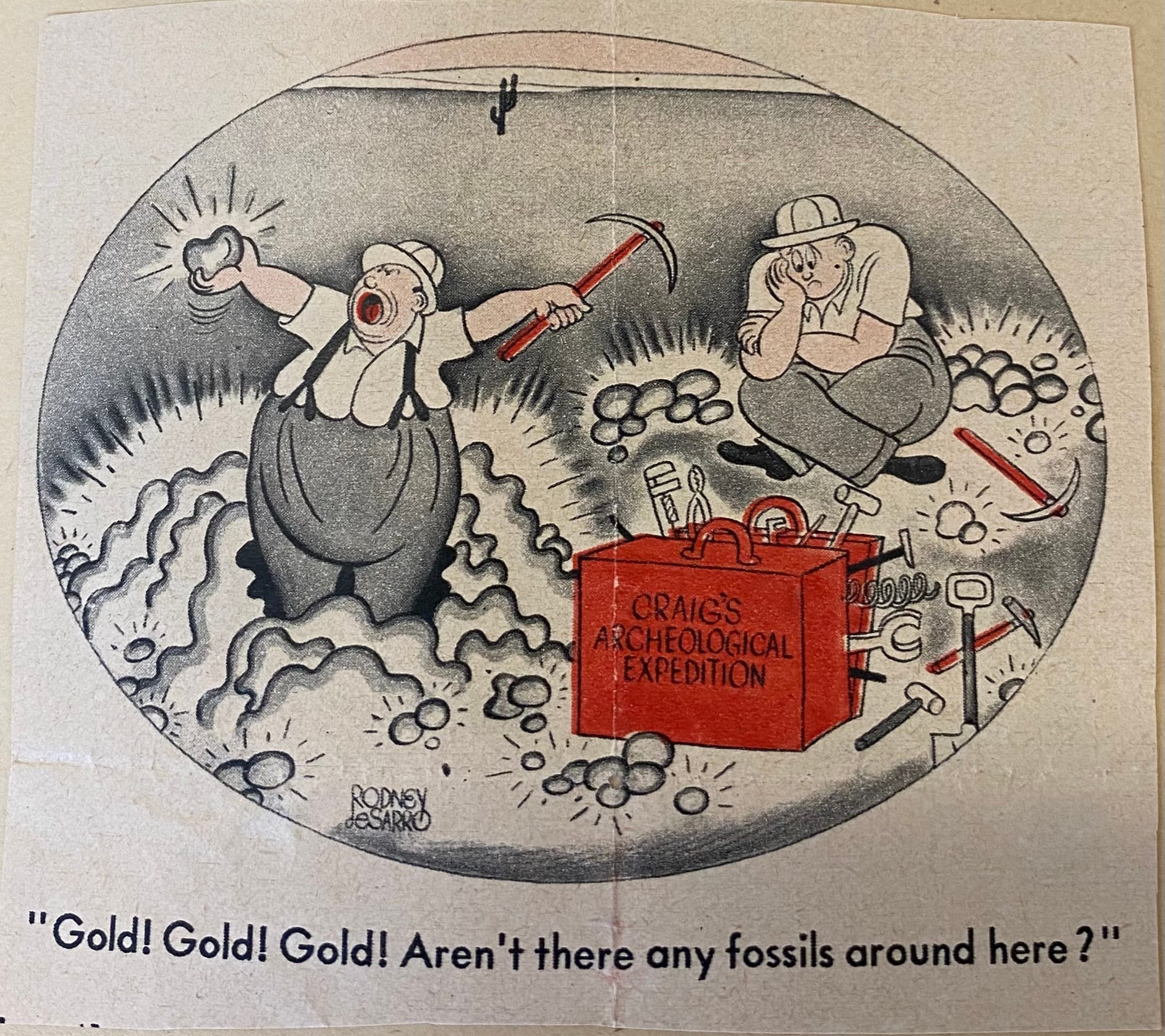

Asher here. Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that knows how to recycle the vestiges of the past. Before we get on with things, a bit of news: I just had a big paleontology feature make the cover of Scientific American, and I'm quite proud of it: it's the story of a scientist who argues that 2.1 billion-year-old African specimens show complex life appearing 500 million years ahead of schedule. His critics say they are — literally — fool's gold. At stake? The question of when and how complex life arose at all. You can read it right here:

Otherwise, things have been very busy. I'm shifting slowly but inexorably into book writing for the UT Press history of paleontology, and as part of that, I've been doing the last bits of archival research and travel necessary to prepare for the major push on the manuscript. And it was in some of that archival research at UT's Vertebrate Paleontology Lab that I stumbled across something fun: a large, handsome, leather-bound scrapbook, belonging to one Ermine Cowles Case.

E.C. Case was one of the workhorses of the second generation of American paleontologists, a sharp-eyed researcher who tasked himself with cleaning up the scientific messes his predecessors had created amid their wild feuds, and then struck out into other areas of interest, particularly the early Permian beasts – like Dimetrodon – of the Texas redbeds. "Dr. Case had the gentlemanliness modified by a certain individuality one finds so often in the west," one obituary writer observed. "He was at home in a drawing-room but the sack of Bull Durham [loose leaf tobacco] went with him.” He was a good writer with a solid grasp of ecological principles, and an astute observer of his own field: when a student of his inquired about pursuing a career in academic paleontology, Case fixed him with a gimlet eye and asked if he was a damn fool.

That said student, Jack Wilson, ended up being a major figure in Texas paleontology himself does not disprove the aptness of the question: it was, and remains, a very difficult business to make a living in. But Case and Wilson had a close enough relationship that Case's scrapbook of paleo-ephemera – clippings of cartoons and poems he'd clipped out or squirreled away after people sent to him – ended up in Wilson's papers, and thus at the University of Texas.

While it wasn't particularly germaine to my research, it so delighted me that I found myself going through it page by page, photographing the bits that delighted me the most.

So today, dear readers, I offer you a selection of my favorite bits and pieces of E.C. Case's collection of early 20th century paleo-pop culture. Some are thought-provoking and lovely. Some are absolutely hackneyed, the product of people clearly working on tight deadlines and reaching for the first available jokes. (A few appear to date from before they invented punchlines.) And some made me genuinely laugh.

It's Heat Death. Stay with us.

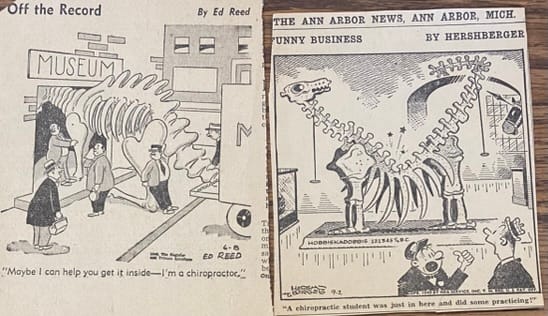

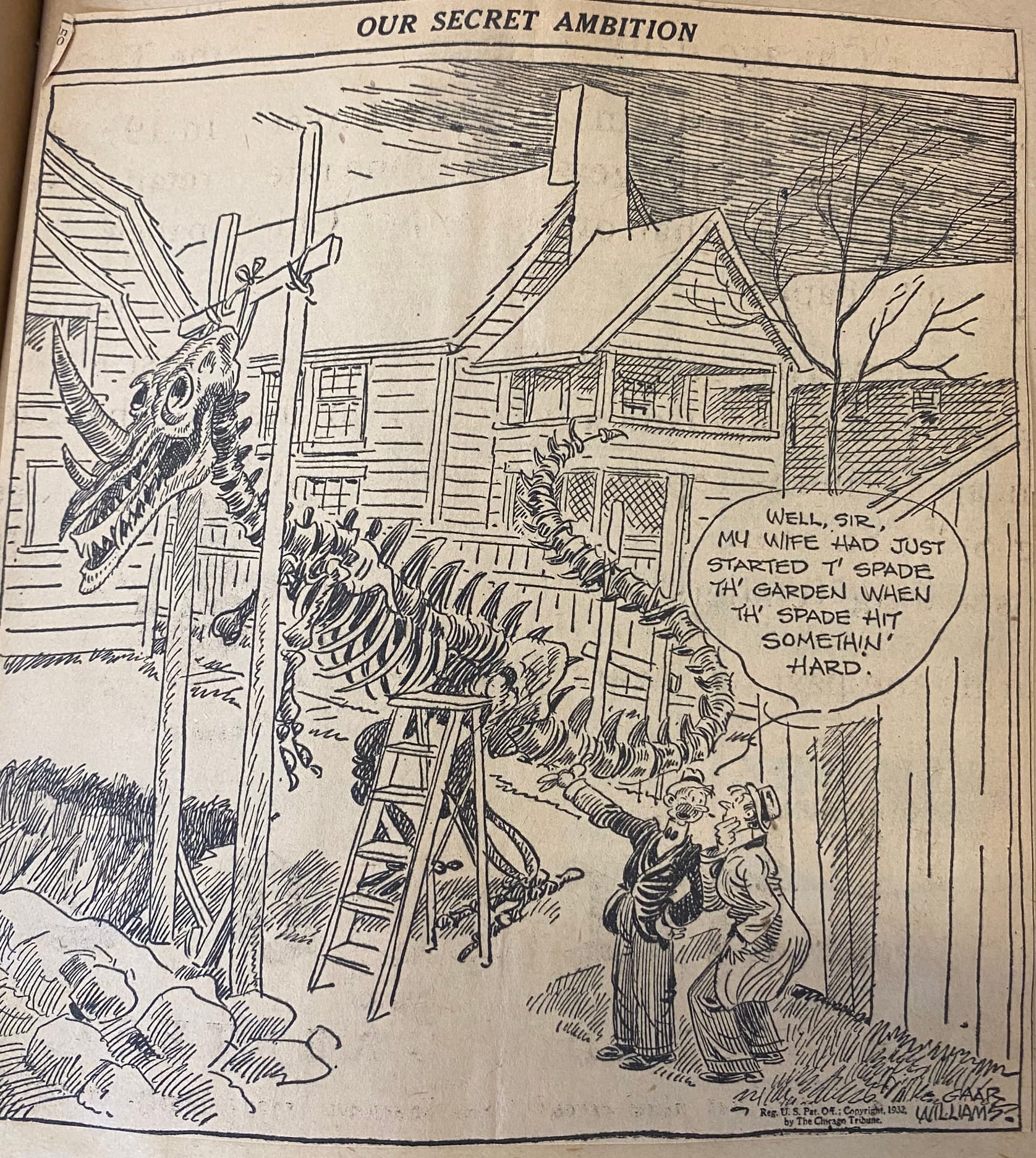

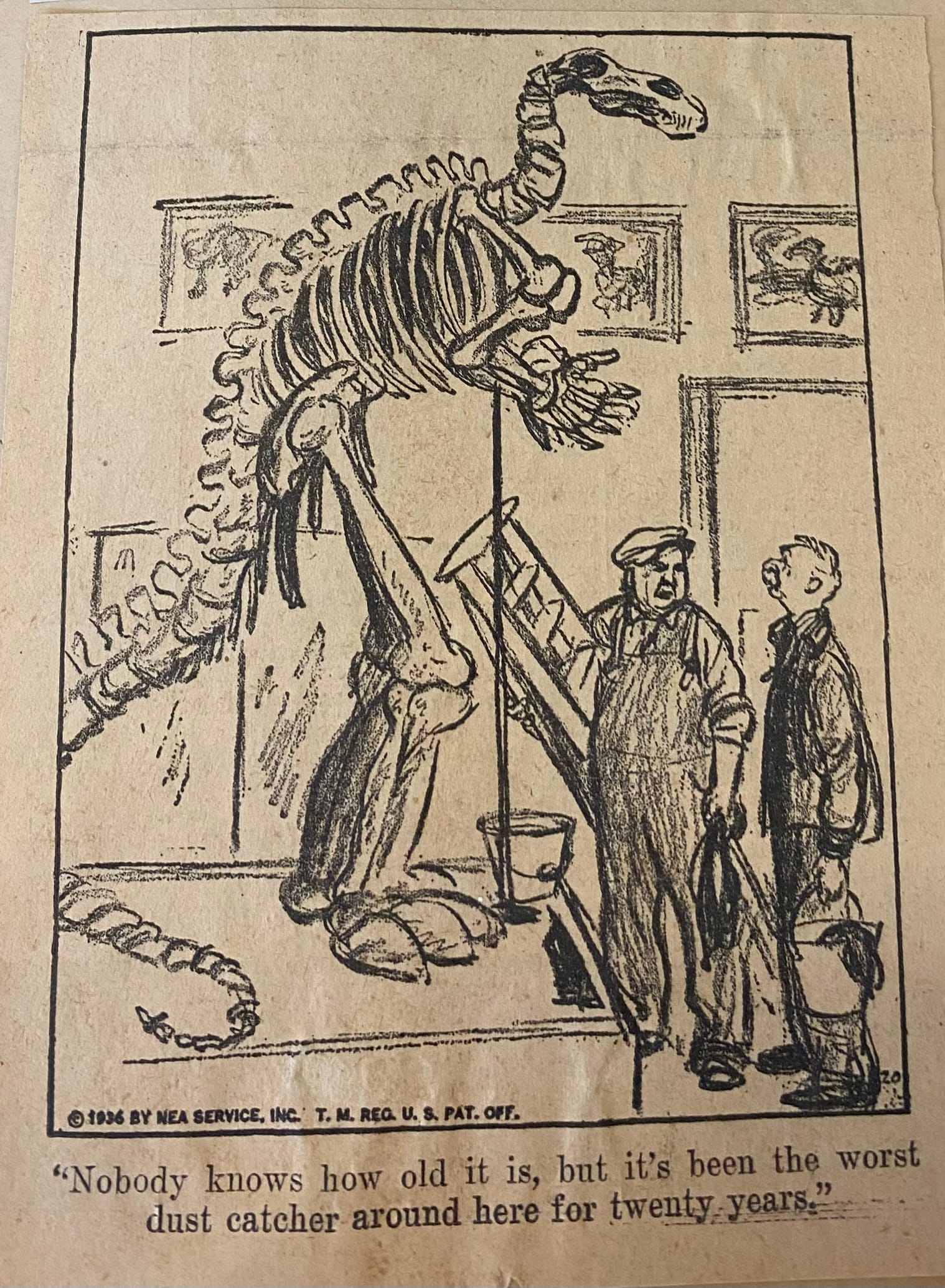

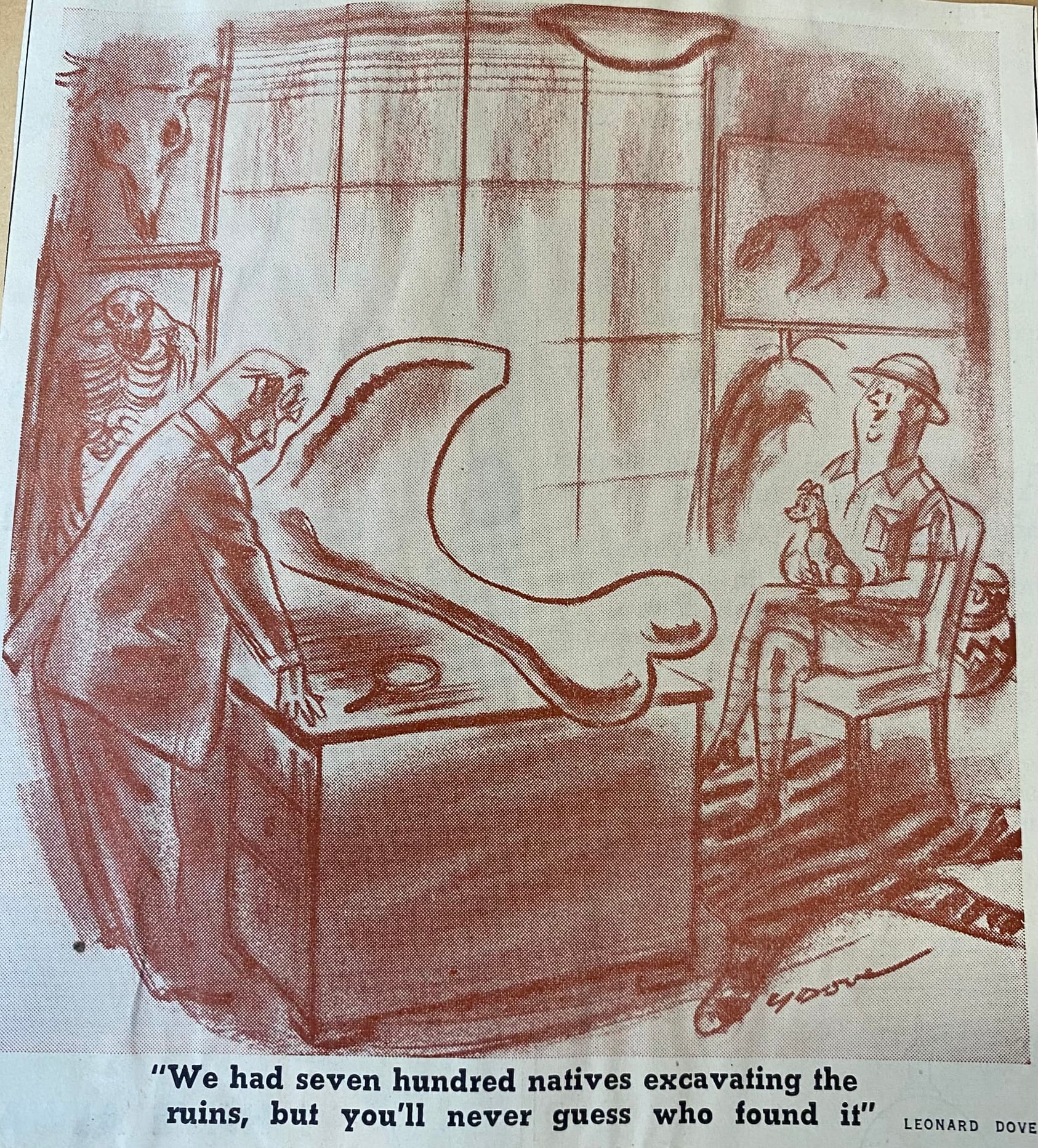

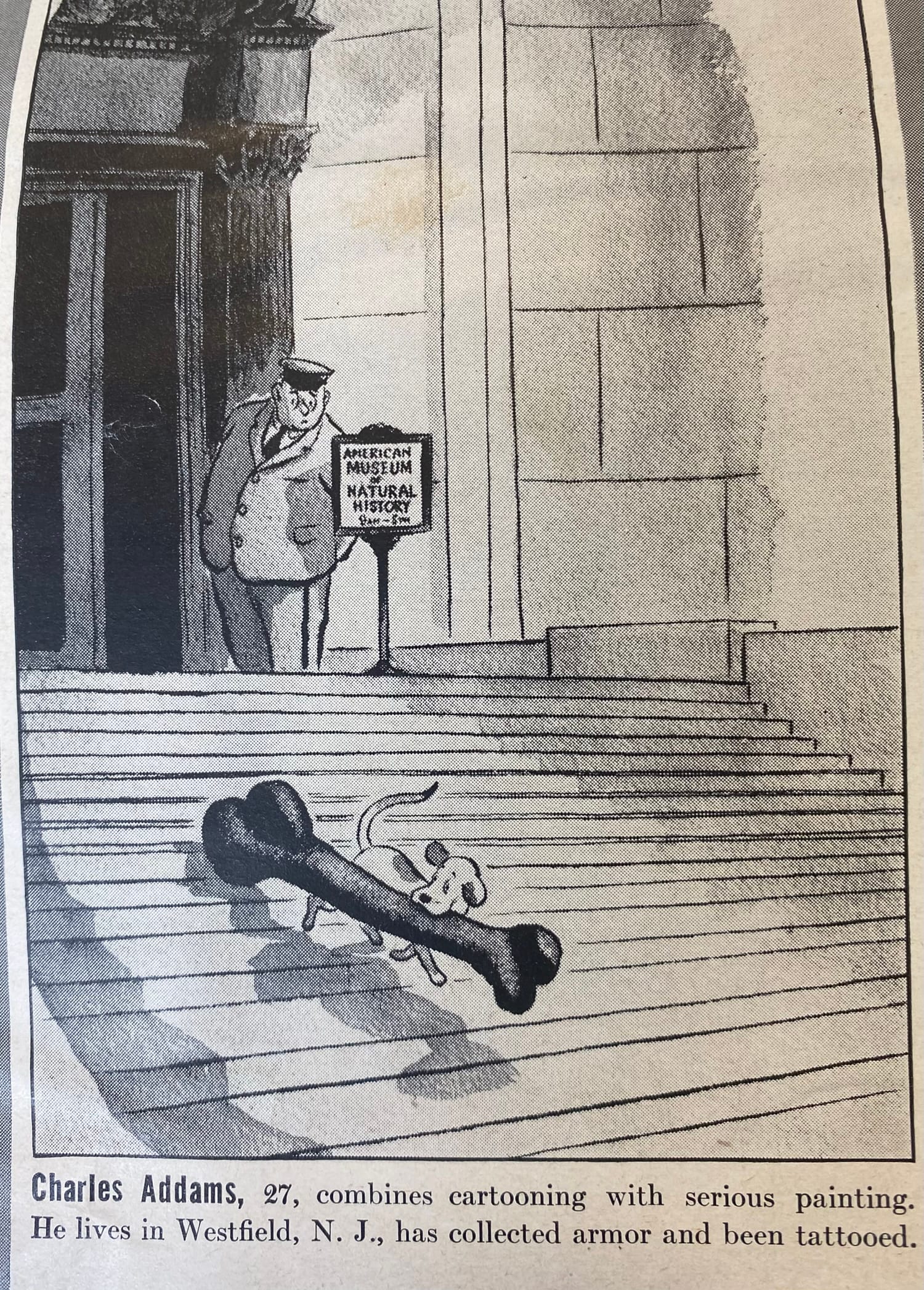

The development of mounted fossil displays is too big of a topic to get into here. But such exhibitions at the American Museum of Natural History and other institutions – part science, part circus-act, part multi-media art – made a big impression on audiences, including cartoonists, who found the topic of giant skeletons lent itself to certain obvious jokes.

The pseudomedical field of chiropractics – the resetting of out-of-alignment bones – was developed, by the way, in 1895 by a man who claimed to have been taught it by a ghost.

Quite a few of the cartoons also have fun with the idea of the working-class schmo – janitor or security guard – forced to deal with such outré things as reconstructed skeletons.

Langdon Smith (1858-1908) is generally forgotten today. As a young man he served in the American army during its wars against the Comanche and Apache peoples, became a war correspondent covering the campaign against the Sioux, and then went on reporting through the Spanish American war for Hearst's New York Journal before transitioning mostly to sports writing. But he also found time in 1895 to pen a few stanzas of a lushly romantic poem, published in full in the New York Journal sometime before 1906. After his early death, "Evolution" was published in an illustrated and annotated book form as Evolution: A Fantasy.

Evolution

By Langdon Smith

When you were a tadpole and I was a fish

In the Paleozoic time,

And side by side on the ebbing tide

We sprawled through the ooze and slime,

Or skittered with many a caudal flip

Through the depths of the Cambrian fen,

My heart was rife with the joy of life,

For I loved you even then.

Mindless we lived and mindless we loved

And mindless at last we died;

And deep in the rift of the Caradoc drift

We slumbered side by side.

The world turned on in the lathe of time,

The hot lands heaved amain,

Till we caught our breath from the womb of death

And crept into life again.

We were amphibians, scaled and tailed,

And drab as a dead man's hand;

We coiled at ease 'neath the dripping trees

Or trailed through the mud and sand.

Croaking and blind, with our three-clawed feet

Writing a language dumb,

With never a spark in the empty dark

To hint at a life to come.

Yet happy we lived and happy we loved,

And happy we died once more;

Our forms were rolled in the clinging mold

Of a Neocomian shore.

The eons came and the eons fled

And the sleep that wrapped us fast

Was riven away in a newer day

And the night of death was passed.

Then light and swift through the jungle trees

We swung in our airy flights,

Or breathed in the balms of the fronded palms

In the hush of the moonless nights;

And oh! what beautiful years were there

When our hearts clung each to each;

When life was filled and our senses thrilled

In the first faint dawn of speech.

Thus life by life and love by love

We passed through the cycles strange,

And breath by breath and death by death

We followed the chain of change.

Till there came a time in the law of life

When over the nursing sod

The shadows broke and the soul awoke

In a strange, dim dream of God.

I was thewed like an Auroch bull

And tusked like the great cave bear;

And you, my sweet, from head to feet

Were gowned in your glorious hair.

Deep in the gloom of a fireless cave,

When the night fell o'er the plain

And the moon hung red o'er the river bed

We mumbled the bones of the slain.

I flaked a flint to a cutting edge

And shaped it with brutish craft;

I broke a shank from the woodland lank

And fitted it, head and haft;

Than I hid me close to the reedy tarn,

Where the mammoth came to drink;

Through the brawn and bone I drove the stone

And slew him upon the brink.

Loud I howled through the moonlit wastes,

Loud answered our kith and kin;

From west to east to the crimson feast

The clan came tramping in.

O'er joint and gristle and padded hoof

We fought and clawed and tore,

And cheek by jowl with many a growl

We talked the marvel o'er.

I carved that fight on a reindeer bone

With rude and hairy hand;

I pictured his fall on the cavern wall

That men might understand.

For we lived by blood and the right of might

Ere human laws were drawn,

And the age of sin did not begin

Til our brutal tusks were gone.

And that was a million years ago

In a time that no man knows;

Yet here tonight in the mellow light

We sit at Delmonico's.

Your eyes are deep as the Devon springs,

Your hair is dark as jet,

Your years are few, your life is new,

Your soul untried, and yet --

Our trail is on the Kimmeridge clay

And the scarp of the Purbeck flags;

We have left our bones in the Bagshot stones

And deep in the Coralline crags;

Our love is old, our lives are old,

And death shall come amain;

Should it come today, what man may say

We shall not live again?

God wrought our souls from the Tremadoc beds

And furnish’d them wings to fly;

He sowed our spawn in the world's dim dawn,

And I know that it shall not die,

Though cities have sprung above the graves

Where the crook-bone men made war

And the ox-wain creaks o'er the buried caves

Where the mummied mammoths are.

Then as we linger at luncheon here

O'er many a dainty dish,

Let us drink anew to the time when you

Were a tadpole and I was a fish.

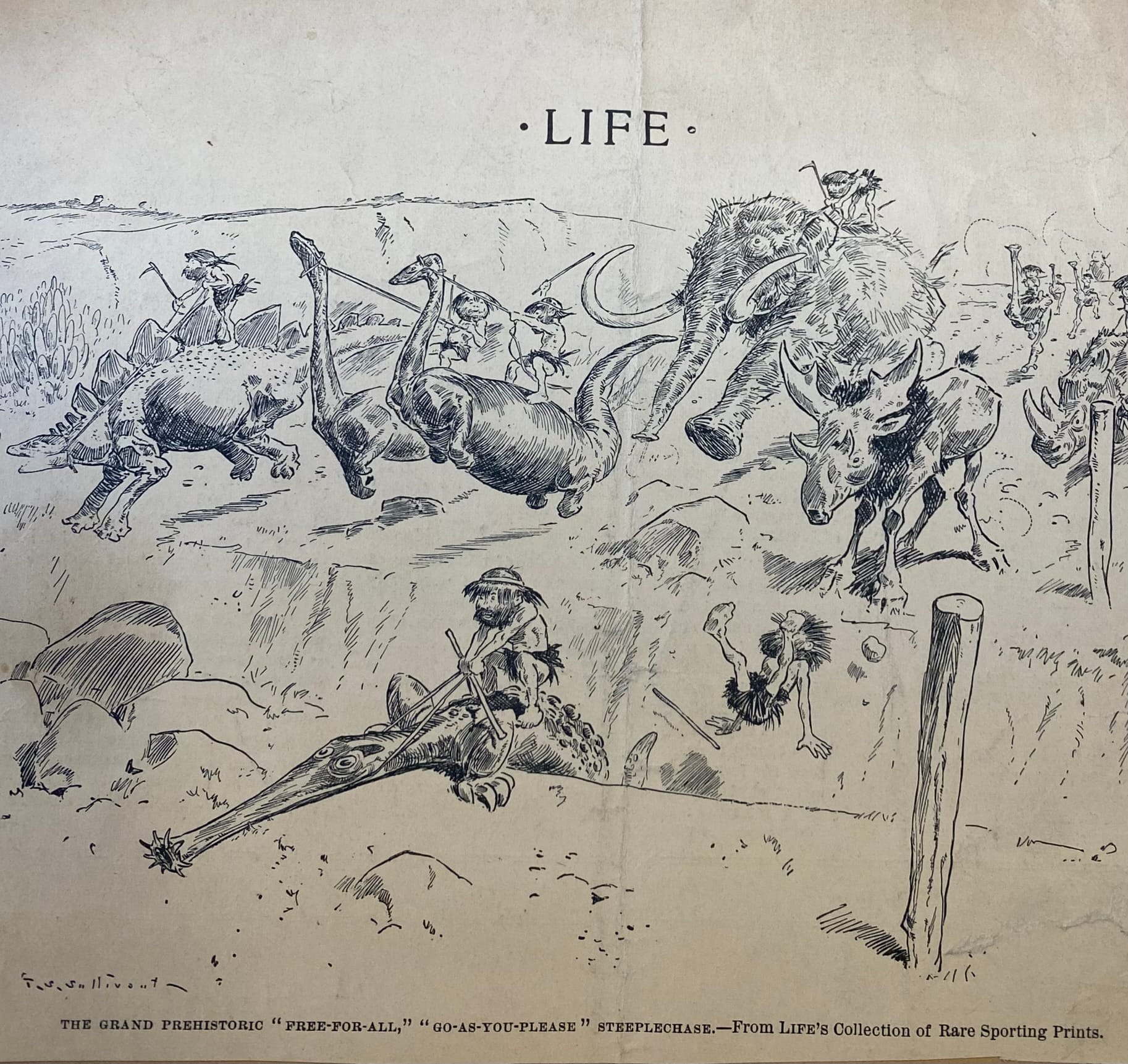

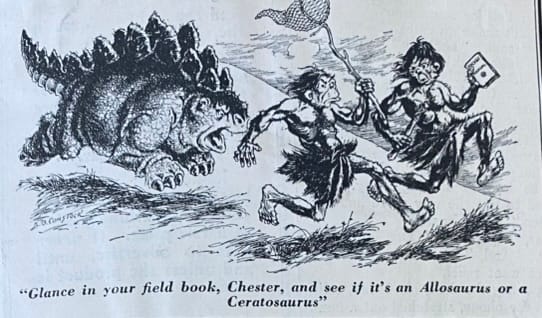

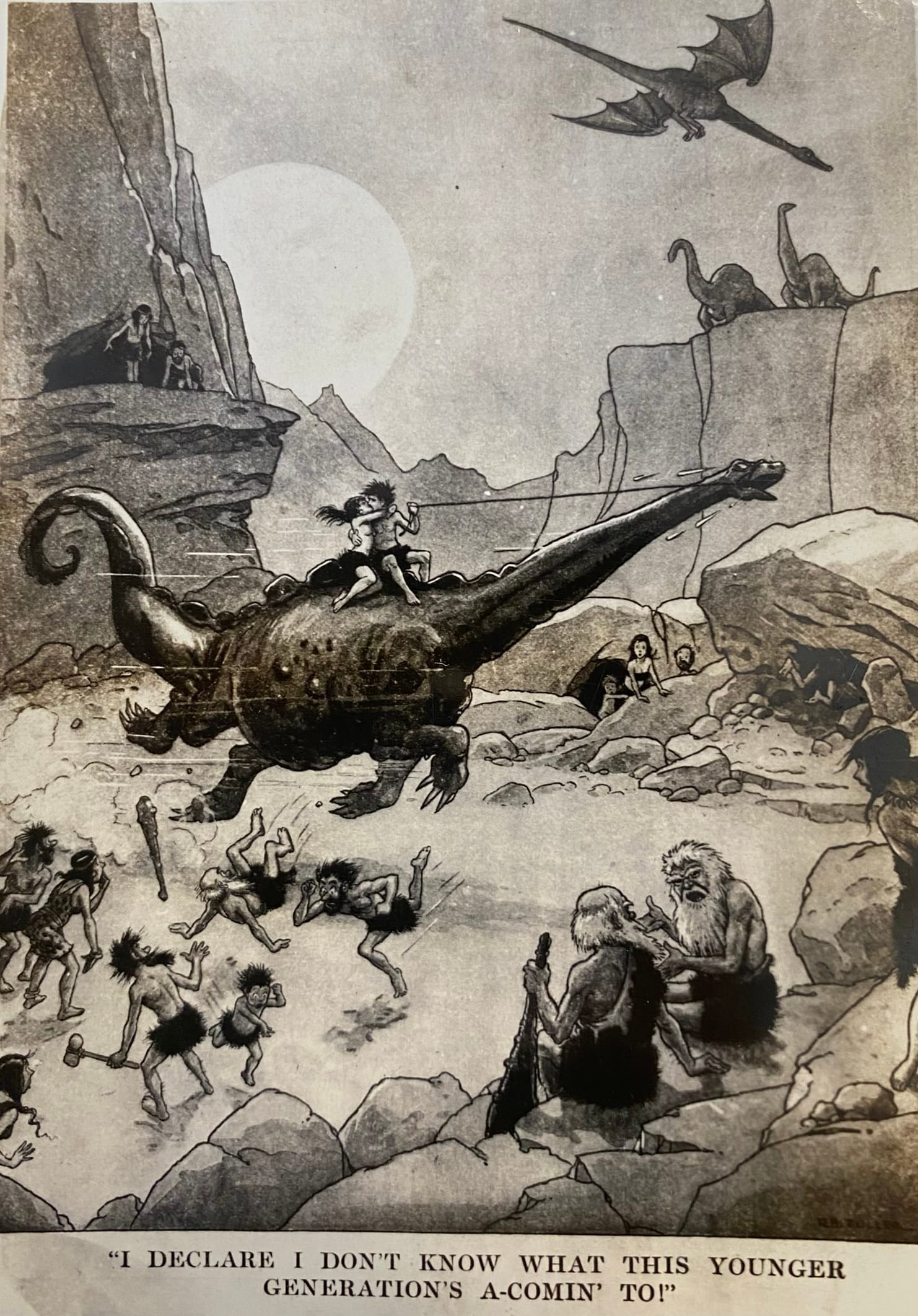

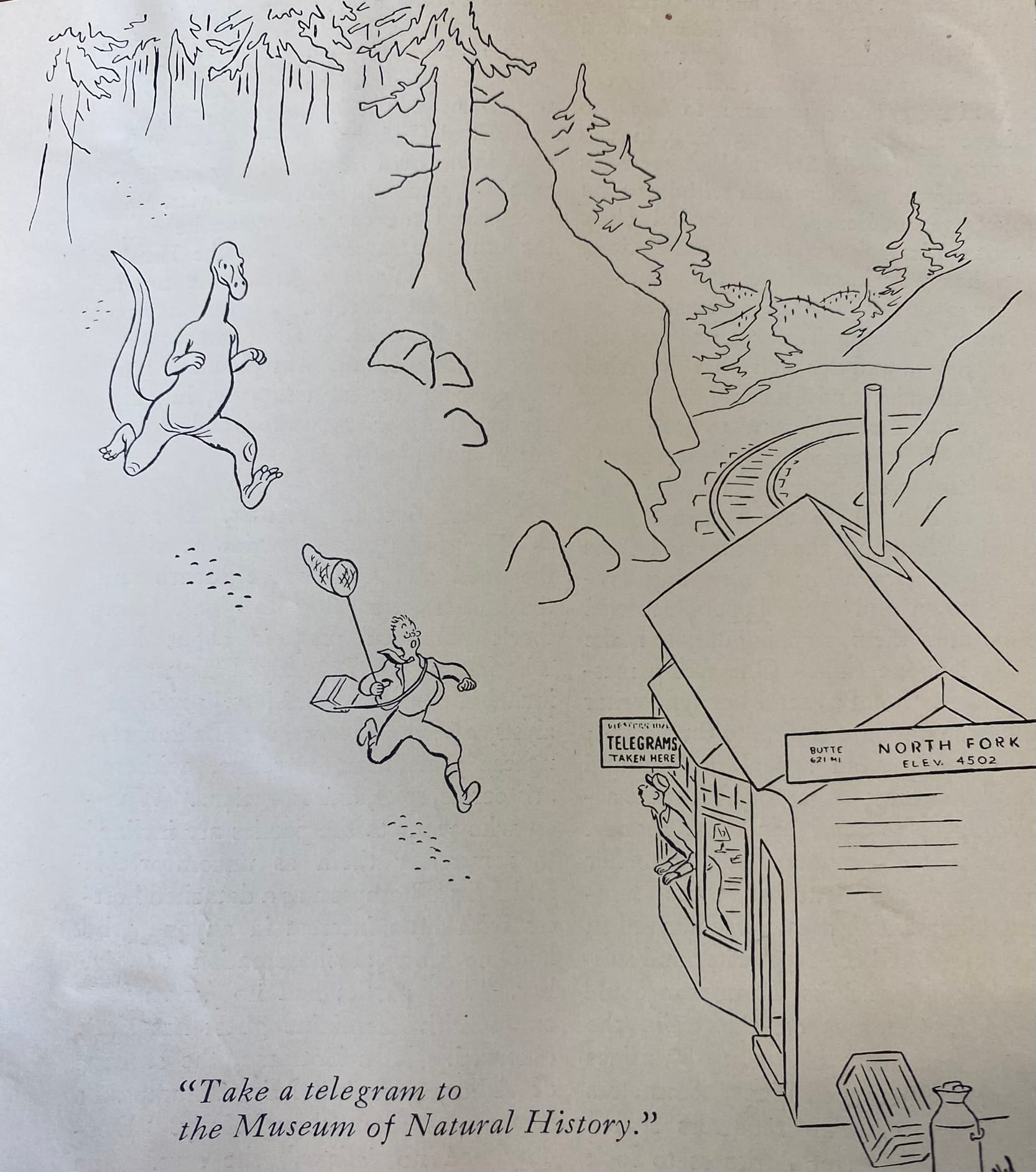

As any reader of Heat Death knows, non-bird dinosaurs and people never mixed while alive. But the combination of dinosaurs and cavefolk into a sort of mythic prehistory has been an extremely durable one, in part because it makes for such a compelling package (it's fun to imagine dinosaurs and humans interacting) and in part because cartoonists just can't resist using it to comment on modernity. This tendency would find its apex, of course, in the 1960s Hanna-Barbera cartoon The Flinstones: a sitcom where the central joke was that, dinosaurs and furs aside, it was a straight-down-the-middle American domestic comedy.

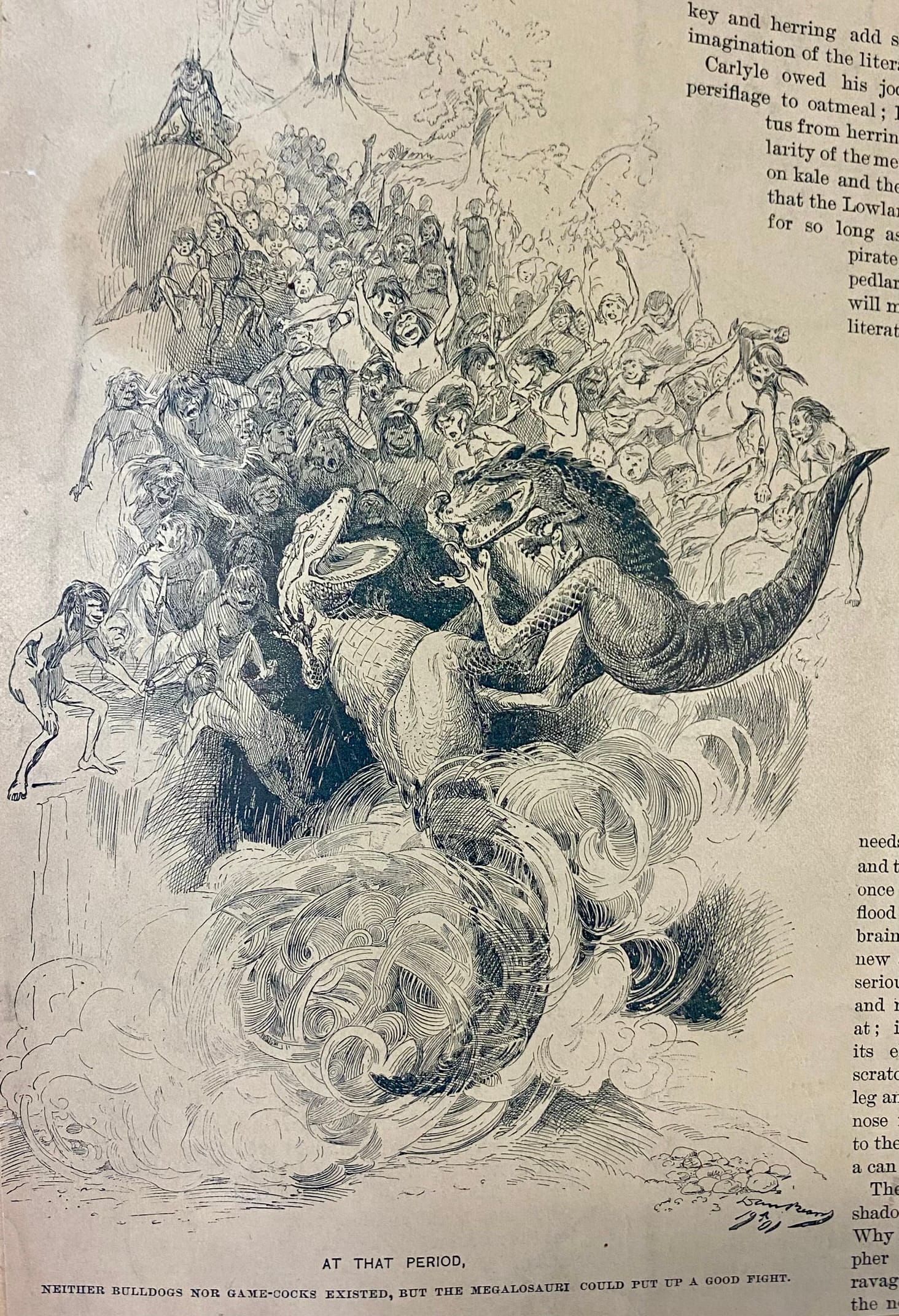

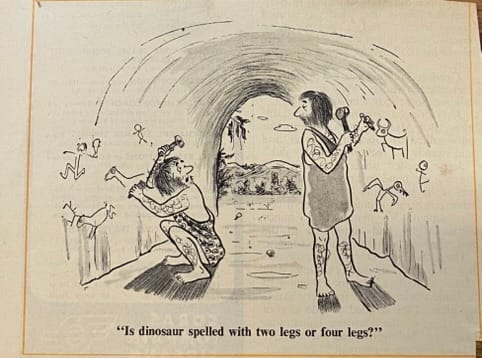

Here, as collected by Case, are some protypical examples. First off, two examples from LIFE Magazine, from the era where cartoons tended to be droll or absurdist but not – as such – funny.

A somewhat ironic note about the above is that – in equating big theropods with roosters to make the joke work – it ends up looking rather modern. (But is likely a riff on this rather famous Charles Knight painting.)

It is, of course, neither. It's not clear to me whether the cartoonist knew this and was adding another layer to the joke, or was just picking names out of a hat.

SIT UT EST, AUT NON SIT

Mary E. Gooley

July 1948

Many thousand years ago,

Remains of hardened mudflats show,

A dinosaur sat down.

What had he done that he should be

Preserved into Eternity?

Was he the noblest of his kind?

Did he excell in form or mind?

We cannot tell, we only say

He sat down in the mud one day.

And was he thinking as he sat

Of what this silly world was at?

Or why he was not born with wings?

Or other interesting things?

We cannot tell, we only say

He sat down in the mud one day.

Beware, oh man, you never know

What traces to the future go.

Beware where you sit down.

Dinosaur skeletons in museums also tended to summon up another very obvious joke.

Here are two examples from The New Yorker, including an appearance by the great Charles Addams, creator (of course) of the Addams Family.

The story of horse evolution is a pivotal one in American paleontology, in large part because the cold, patrician researcher Othniel Charles Marsh (1831-1899) devoted considerable time to piecing together a sequence of fossil remains charting a line of descent from the rodent-like dawn horses of the Eocene to the modern, single-toed giants of today. His displays of such collections to visiting researchers made him the toast of European paleontology – and eventually, in roundabout ways, inspired the following poem.

The Lay of Lost Toes

H.C. Sadler

Long, long ago, so the story goes,

The horses were little and had four toes,

And aeons before, there were doubtless alive,

High-toned Hippi possessed of five.

But after a while they began to feel

That so many tootsies were not genteel;

They didn't need such a number, so

They decided to drop the superfluous toe,

And the chief Eohippus pronounced a decree

That horses' toes be reduced to three.

All the artistic and bon-ton Hippi,

Who lived out west of the Mississippi,

Adopted the latest style in toes

And abandoned the the name Eohippus to those

Plebeian creatures who needed a grip,

And came to be known as the Mesohip.

But after a few odd millions of years,

With minor fashions in noses and ears,

There finally dawned the terrible truth

That somehow or other they'd lost a tooth.

As their teeth grew longer, though fewer in toto,

They changed their name from Meso- to Proto-.

But the grave old Elders whose teeth were worn,

And on each of whose toes was a separate corn,

Were heard to observe that their principal woes

Were due to their teeth and numerous toes.

But times soon changed, and a lower class

Of course, rude Hippi, more like the ass,

With great big bodies and longer humerus,

Became so strong and so very numerous

That they rose and demanded that once and for all

They abandon the mincing three-toed crawl.

The herd assembled and hailed as a leader

One who had gained renown as a speeder.

He whinnied: "to hell with the tribe of Hippus

And the fads in toes that they always slip us.

We'll call ourselves by the 'Equus' name

(It's something different but means the same)

And as common Equi must mainly run,

I move that our toes be reduced to one!

So this is the tale of the ancient lore

How the toes were changed from five to four.

From four to three,

He came in course

To end at last

A one-toed

Horse.

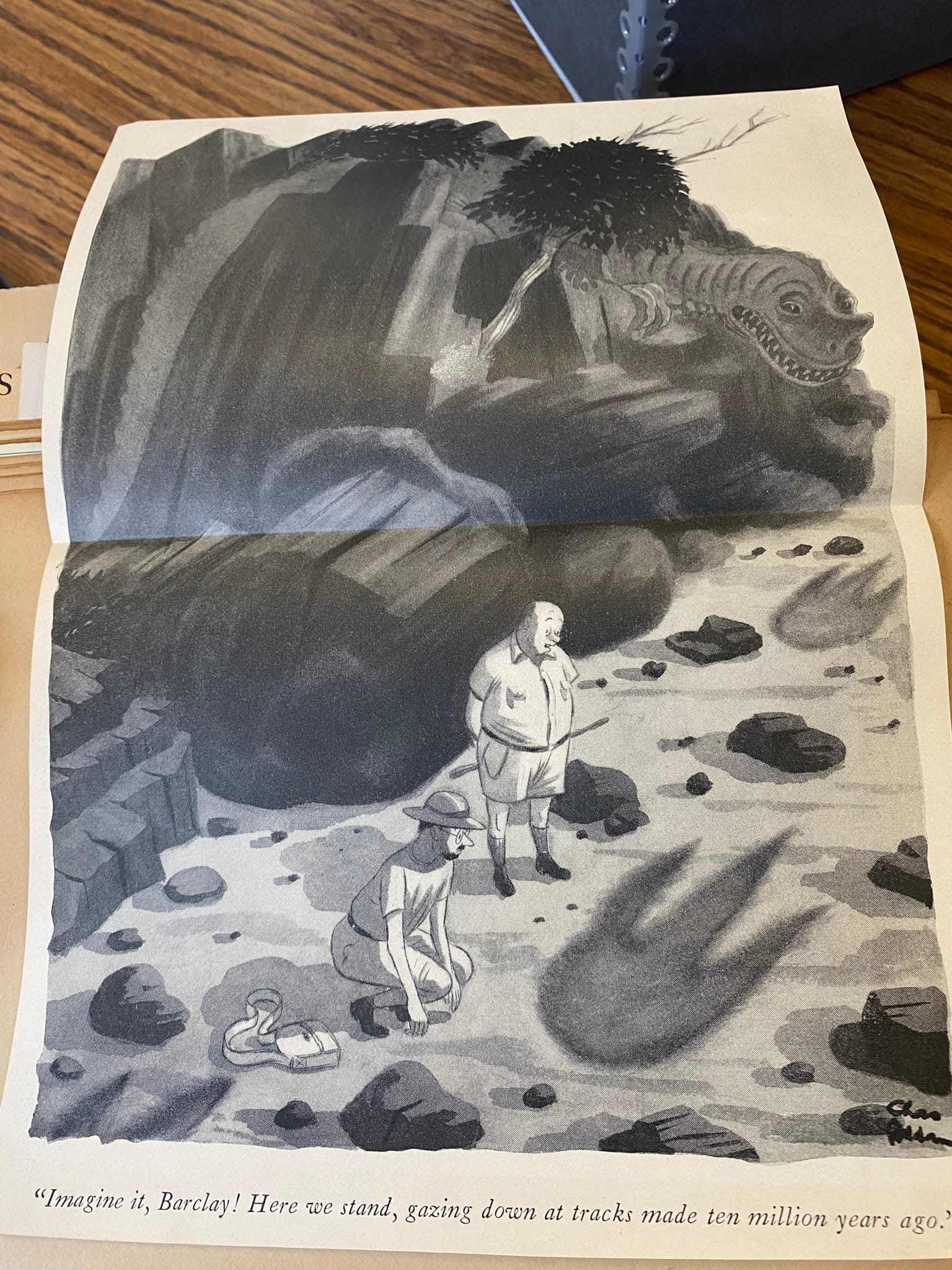

If cavefolk and dinosaurs are a natural theme to the deadline-stricken cartoonist, so is the unexpected survival of creatures assumed to be extinct. Here's Addams, again, working in his more usual style of the pleasantly macabre.

I can't look at this one without laughing.

To contemplate prehistory is, inevitably, to contemplate certain realities of life – and death.

O! as in Oblivion

David McCord

November 26, 1949

The pterodactyl ceased to fly

And man has ever wondered why;

Tyrannosaurus cooked his goose

For reasons that appeared abstruse;

Deep in the Eocemic sea

The Zeuglodon's an absentee;

The trilobites by trillions quit

Perhaps because they didn't fit,

And something slew the giant sloth

Ere Job beheld the behemoth,

But does it matter? Ye, it does;

You cant revive the is it was.

The roc and griffin ne're were–

The lucky ham, the lucky her!

And that, at least in part explains

Their lack of petrified remains.

All footed, finned and feathered things

Had better beat feet, fins and wings,

And they that wiggle, inch or crawl

Had better hump their under all.

The fossil years without a doubt

Bear witness that we're going out

Lock, stock, and barrel, hip and thigh:

And this means you, and this means I.

This has been Heat Death. We're entirely reader-supported independent media: if you like what we do here, feel free to subscribe: paid memberships are just $2 t0 $5 a month. (Or you can always leave us a tip.)

We'll be back soon with more musings on past, future, and all the crises in between. Until next time, keep your eyes on the prize.

Member discussion