Perhaps I'll Be A Bird One Day

Saul here. The line between humans and birds is not so bright as it sometimes appears. Let me give you an example, adapted from the Legends of Moyobamba.

Once in the foothills of the Andes, there lived a little boy who couldn’t keep his big, stupid mouth shut.

This little boy was famous for his natty costume — a bright yellow jacket and a pair of black, black pants — and his habit of going about telling everyone’s business. Often, he told it wrong. But not always. Not on the day he ran through town with a fateful new story.

“Everyone, everyone!” he cried. “You know Mama Licu — the old lady up the hill? Well I saw that anciana flying on Friday night above the mountains on her broom — a fairy in disguise!”

No one paid much attention to this little burlón — none, except Mama Licu herself. Because in this case, the little boy in the black pants and yellow jacket had told the truth. Mama Licu was, in fact, a powerful fairy. And when the rumor got back to her, she turned him into a little bird — gregarious, chatty, with a black, black body accented with stripes of the brightest yellow.

Was this a punishment? I’d argue it wasn’t. Perhaps, instead, it was a revelation: the false front of the little boy unmasked to reveal the chattering paucar bird beneath.

Today you’ll find his descendants — known among anglo types as the yellow-rumped cacique — on cleared fields across outer Amazonia, living a life not so different from the village he grew up in. They’re clever birds, excellent mimics, building their hanging nests from sticks and mud. They like to live on trees inhabited by colonies of aggressive wasps, who protect the paucar colonies without disturbing them. They also prefer trees that are surrounded by great moats of grass, the better to see enemies approaching.

Since tall Brazil Nut trees still dominate fields cleared for cattle, paucar are a bird of rare distinction: one that actually benefits from human deforestation of the Amazon.

Nor has the paucar abandoned the villages he was once banished from. Legend has it he arrives in villages to sing in advance of important letters and telegrams — and perhaps, while there, to twit the local roosters with an excellent imitation of their call.

Peruvian villagers, noting the paucar’s intelligence, repay it with the highest form of flattery: they deliver his head, still warm, to be eaten by their children, that they may become intelligent — and, like the paucar, quickly learn any new thing they may be taught.

Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that knows what a bird in hand is worth. The rains have finally come to Austin, coaxing out long-awaited cool temperatures and bringing a second spring flush of wildflowers to many a garden. With them has come the fall migration, a procession of songbirds trooping dutifully south to follow the warm weather. In Asher's garden alone, the seed-heads of sunflowers and other yellow blooms have provided rich snacks for traveling goldfinches, juncos, and other hyperactive little jobbies. In this, they're fulfilling part of the reason he planted them: to attract the melodic little dinosaurs that so enthrall us.

The human interest in birds is one of those things you can trace quite far back down are family tree. Before H. sapiens ever made it to Europe, the Neanderthal people caught golden eagles to harvest their feathers and talons. The folk of the ancient, 7,300 year old Çatalhöyük painted vulture spirits on the walls of their mud-brick rooms. And of course, indigenous societies the world over have looked at birds and seen — if not always a brother people — then certainly cousins, diverged and transformed from us long ago.

Indeed, the people that "Western" Europeans most often claim as our progenitors – the classical Greeks – have some folktales of their own about the relationship. Notably, when the philosopher Plato was asked to give the definition of a man, he replied sagely that it was simple: a featherless biped. To which the cynic Diogenes produced a plucked chicken and cried: "Behold! A man!" A sharp-edged joke at Plato's expense? Absolutely. But he might have been on to something.

Asher's been interested in this stuff for a while, and about two years ago, he pitched a story exploring some of these connections to a magazine of some repute. Now, we’ll let you in on a little secret of the journalism business: sometimes stories just don’t work out for one reason or another. This piece was commissioned and written, but with one thing or another, it never made it to print.

But we — like the paucar, who weaves his nests from whatever’s around — take the view that thriftiness is next to godliness, and anyway, Asher put enough work into it that he’d like people to actually see it.

So today, we have four more tales for you from the frontier where folklore meets science, about places where the cultures of birds and humans intersect. From Australia’s fire-spreading hawks to the Icelandic ducks who pay rent in eggs, these birds offer a glimpse into a fairy-tale world that is not only deadly serious, but that far predates our own understanding of humans and animals as separate.

It’s Heat Death. Stay with us.

The Human Flocks

Asher here. Humans have exploited birds for as long as the two groups have lived alongside each other. Across the globe, traditional peoples have had thousands of years to study and manage their feathered neighbors, and many have developed deeply intimate relationships with the species in their respective orbits.

Some they’ve closely studied, enfolding their knowledge in oral tradition. Some they’ve partnered with — as with Mongolian eagle falconers or the famous symbiosis between Yao people of Southern Africa and the honeyguide — or domesticated, like junglefowl, waterfowl, and doves. And many they’ve harvested for generations, gathering eggs, feathers, and meat, developing intentional and sophisticated practices around management and trade.

Today, it’s common to assume that the careful study and management of birds is a modern phenomenon, developed through post-enlightenment scientific practices. But that viewpoint overlooks the complex traditions of indigenous peoples across the globe — traditions which have often been ignored or actively suppressed over the course of European colonization.

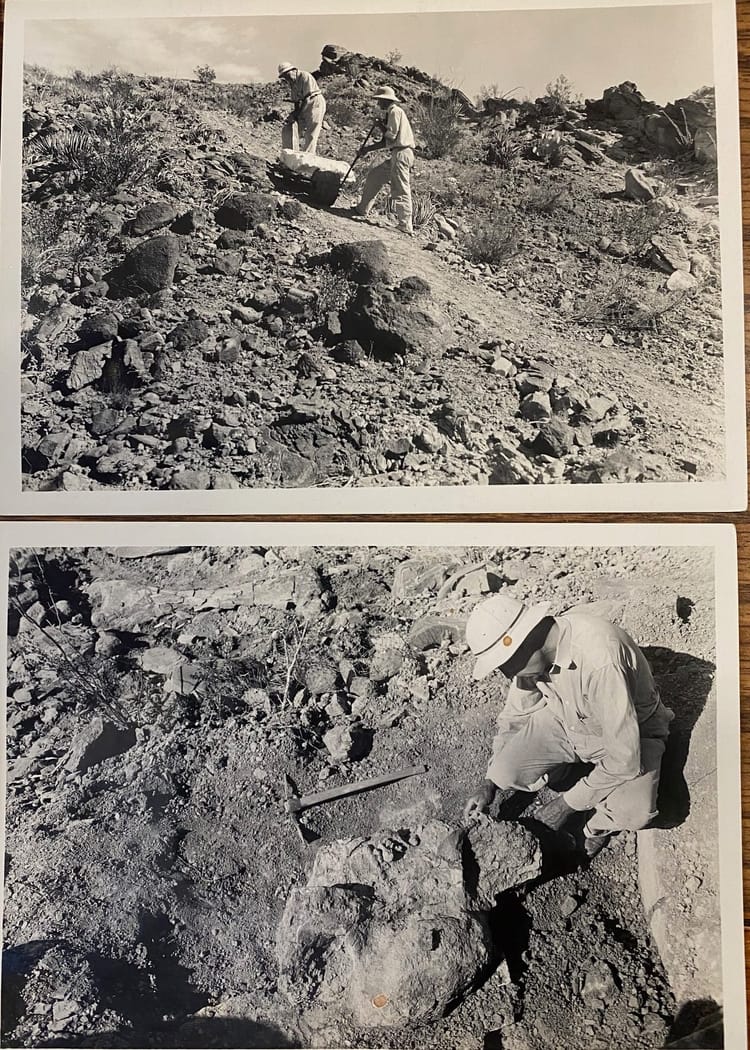

But over the past few decades, zoology-inclined archeologists and anthropologists have begun paying a lot more attention to indigenous practices. Using a combination of new archeological technologies — including digital scanning, morphometrics and improved carbon dating — researchers are increasingly recognizing the ways that traditional cultures have wrangled bird populations for hundreds, even thousands of years. Here are a few of them.

FIREHAWKS: ORAL TRADITIONS

In the dry season of Australia’s Arnhem Land, many fire fronts on the savannah are accompanied by the spiraling, diving forms of black kites and the keen-eyed little brown falcon. Both species are keen to feast on the small marsupials and reptiles flushed out by the flames — and according to Robert Redford, a member of the Rembarrnga people and a senior ranger with Mimal Land Management, they sometimes take matters into their own beaks.

Like many land managers in Australia, MLM’s work involves using traditional controlled burning regimes to prevent conflagrations during the dry season. Sometimes when they finish a fire, Redford says, they’ll see a bird swoop down, grab a burning stick, and “take it to another place. You’ll look up and see that another fire’s coming. It’s a lot of humbug for us.”

The oral tradition of the Rembarrnga — as well as other northern Aboriginal groups — is full of stories of the brown falcon, whom Rembarrnga call garrkan, acting as a fire spreader. The birds play a central role in Rembarrnga funerary ceremonies like the hollow log ritual Lorrkon, in which initiates embody by picking up lit sticks from the fire and carrying them to unburned grass.

For hundreds of years after Australia’s colonization, most European researchers dismissed such stories outright, or attributed them to occasional accidents. Yet when ornithologist Mark Gosford began looking into the practice, he collected multiple reports from non-aboriginal ranchers about black kites moving fire fronts up hillsides and across rivers, occasionally causing previously contained burns to get out of control — as well as over 20 detailed interviews with aboriginal witnesses about the brown falcon’s activities.

“When I talk to non-aboriginal people and or land managers — apart from those we’ve recorded — it’s along the lines of ‘its an accident’ or ‘it just doesn’t happen’ or birds just aren’t like that,” says Bob Gosford, an ornithologist who’s worked to record ethnographic accounts and first-hand sightings of the behavior. “But for the aboriginal people we talk to, it’s wholly unremarkable.”

Why? Controlled burns — and an accumulated millennia of observation of local, fire-following birds — are a key aspect of traditional land management in Arnhem Land. These fire practices, which are used to encourage healthy savannahs and forestall deadly wildfires later in the season, were largely suppressed throughout most of Australia’s colonial history — just like similar practices in the Western United States.

But in 1976, major legal decisions delivered swaths of the Northern Territories back to Aboriginal ownership, allowing for the return of traditional burns — and making the recognition of indigenous knowledge crucial in an increasingly fire-prone landscape.

As it happens, Redford says, Rembarrnga lore holds that they learned to use flame to shape landscapes by watching the brown falcon, who in turn comes to their fires to scope them out for potential prey. “We used to copy that bird, spreading that fire,” Redford said. “To make the grass come up green. So animals can come back.”

And for as much of a headache as bush’s firebirds can be, rangers largely accept that the firebirds — whether brown falcons or black kites — have an agenda of their own, which doesn’t always take people’s into account. It’s the sort of thing you just have to live with.

“He’s really boss, that bird,” Redford said. “He’s really the land manager.”

CASSOWARIES: KNOWING THE FOREST

Many of the world’s flightless birds vanished after contact with humans. But in the misty jungle valleys and highlands of Papua New Guinea, dagger-toed cassowaries still prowl the forests, eating fruit and dispersing seeds through their dung. These modern dinosaurs are formidable, secretive, and not to be trifled with — which hasn’t stopped the island’s peoples from collecting their eggs and raising their chicks.

The bodies of cassowaries have plenty of traditional uses, says Papuan conservationist Mariam Supema. Their shaggy feathers can be used to make skirts and headdresses; their bones can be carved into knives for hunting and cooking. (They’re a good source of protein, too.)

“It can be traded, it can be used as a wedding gift,” Supema said. “If you’re sharing cassowary meat, it’s seen as symbolic of uniting people and strengthening relationships.”

The simplest way to keep these valuable animals on hand is to hatch and rear the young birds in captivity, where they can imprint on humans. But simple isn’t the same thing as easy — cassowary nests are hard to find, and guarded by protective, heavily armed males. Collecting them requires intimate knowledge of the forest, Supema said — including the numbers and movements of the birds within it.

“The hunters’ knowledge is very extensive and impressive,” Supema said — an expertise born of long experience, cultural tradition and careful study of the surrounding jungle. “They can tell when certain species like cassowary are breeding, just by looking at the trees or fruits that are in season during that time — which means they know the right time to go hunting.”

Cassowary themselves play a role in this. “In communities right in the heart of the forest, there are those who refer to the cassowary as ‘the gardener,’ and to their droppings as cassowary gardens,” Supema said. “It shows the forest is healthy.”

This kind of careful observation and harvesting has incredibly deep roots. A recent study of 11,000-9,000 year old fragments of cassowary egg shells — collected from ancient rock shelters in the island’s eastern highlands — showed that most of the eggs had been only a few days away from hatching. That’s a sign of what archeologists call “preferential harvesting,” says Kristina Douglas, an archeologist at Penn State University, which means ancient Papuans knew exactly when to go and fetch the eggs.

“It suggests knowledge of the reproductive ecology of these birds, knowledge of the environments in which resources can be found, potentially people watching or monitoring nests, and the possibility that people are doing this in order to hatch or rear cassowary chicks,” Douglas said.

It’s quite impressive that at least some people living so many thousands of years ago accumulated that knowledge, Supema said — but there’s nothing innate or primordial about in it. It comes from practice and experience — and it’s quite likely that some people died in the process of trying to take cassowary eggs. But eventually, the island’s indigenous peoples arrived at a deep, intergenerational understanding of how to manage and track their large and irascible neighbors.

Papuan communities “know the role the cassowary plays,” Supema said. “Especially those who are hunting and who use the forest a lot for their daily needs and survival."

SCARLET MACAWS: THE FEATHER TRADE

The wildlife trade is nothing new. As long as humans have lived around birds, they’ve prized the feathers of those from distant lands — and have tried their best to set up domestic supplies. In Mesoamerica, Mexica emperors (commonly, if erroneously, called “Aztec”) imported iridescent grackles to beautify their cities. (Here in Austin, we are their unintended beneficiaries.)

In the great pueblos of the American Southwest — as early as 990 AD in Chaco Canyon — people sent out for resplendent scarlet macaws, importing the birds over a thousand miles to raise them for feathers.

Today, scarlet macaws are native to the wet tropical forests of Central and South America. But skeletal remains of over 400 macaws have been recovered from the American Southwest, with the greatest concentration of them — 38 birds — found in Chaco Canyon. Of those, 30 were found at the Pueblo Bonito building complex, says Steven Plog, an archeologist at the University of Virginia. The remains indicate that macaws “were being traded north into southwest, likely in exchange for turquoise that was being moved into Mexico.”

Plog and other archeologists have worked to analyze and accurately date the macaw remains, and turned up a wealth of information. The earliest known birds at Chaco are from the period between 885 and 990 C.E. , he says, suggesting the macaw trade was under way earlier than expected, while the final birds date from between 1015 to 1155 C.E., during the height of the Chaco Pueblos’ architectural growth.

And while a few of the skeletons represent older birds, Plog says, most seem to have died at around 10-14 months. (That brief lifespan does not reflect a want of trying on the part of the Pueblo people: some of the birds show signs of healed injuries, suggesting that those in charge of the birds did their best to nurse them back to health.)

Isotopes in the macaw bones hint at the reason why many of the macaws didn’t last, Plog said — the captives were subsisting on a long term diet of local corn, not the healthiest thing for parrots. The isotopic evidence also suggests that the birds were raised on corn, which suggests that they were brought to Chaco and other southwestern sites as extremely young birds, likely ones that had already been imprinted on people for ease of transport. Once they arrived at Chaco, some were sacrificed, while others were likely kept as a source of feathers. (One room in Pueblo Bonito seems to have been a dedicated aviary.)

But where were the macaws coming from? At the time of the Chacoan great houses, some scarlet macaw populations lived as far north as Tamaulipas, Mexico — about 1,119 miles from Chaco Canyon. Indeed, one piece of genetic research found that 14 of the birds at Chaco hailed from a rare lineage of macaws from southern Mexico — and that 10 of those birds were likely closely related on their mother’s side. That suggests that the birds were likely bred from the same genetic stock — and indicates that Pueblo Bonito got its birds from a dedicated breeding center.

We know that such things existed — in 1250 A.D, a massive macaw breeding facility was established at Paquimé, in the northern Mexico state of Chihuahua. But that location emerged long after the last birds at Chaco had died, suggesting earlier, as-yet undiscovered breeding operations that supplied the desert Southwest with their macaws.

“The macaw has been really important here with indigenous folks since time immemorial,” says Arden Kucate, a Zuni traditional practitioner. The Zuni — who trace their descent back to the peoples of the Chaco pueblos, and hold their ancient villages an religious sites as sacred — macaws are connected to their understanding of their origins, and the bright red feathers are still commonly used in ceremonial regalia and ornamentation for dance costumes. Some of these are heirloom items, passed down through families. Other feathers arrive through our own modern networks of global trade, such as online purchasing, Kucate said.

Unfortunately, the modern wildlife trade has rendered scarlet macaws seriously endangered: commercial usage is limited to protect surviving populations. Today, projects like Feathers for Native Americans gather molted feathers from captive birds and make them freely available for ceremonial purposes, undercutting smugglers.

WATERFOWL: A SUSTAINABLE HARVEST

In spring, the rich, shallow waters of Iceland’s Lake Myvatn absolutely teem with birds. Terns and whimbrel swoop low over the water, and the reeds and shallows throng with a huge variety of North American and Eurasian ducks — at least 10,000 breeding pairs every year.

The people of Iceland aren’t usually what you’d think of when you hear the term “indigenous.” But prior to the Norse arrival in the ninth century, the island was that rarest of historical places: a landmass that was truly empty of humans, home only to a single species of fox and teeming with birds.

The settlers rapidly recognized the lake’s bounty. Today, custom in the lakeshore farms governs the harvesting of eggs from the migrating waterfowl, allowing residents to load up on eggs during the breeding season. By studying the microscopic structure of eggshells at sites like Skútustaðir — a prominent historic farm on the lake with a 1000 year old archeological record — a team of archeologists has traced the practice back a thousand years, making it an example of how cultures can sustainably manage and harvest birds over centuries.

The research began in 2013, when archeologists Megan Hicks and Árni Einarsson began examining eggshells and other bird remains at Skútustaðir, particularly those from the 10th century, middle ages and 17th and 18th centuries. “The egg fragments were minuscule and impossible to identify with the bare eye,” said Einarsson, a biologist with the University of Iceland. But using a scanning electron microscope, they identified characteristic microstructures in each type of egg, allowing them to assign them to specific species. “We can confirm if a certain species was living in the region at the time, and if it was common enough to support harvesting of its eggs.”

The remains of medieval hearths showed that generally, people didn’t hunt grown waterfowl, instead preying mostly on ground birds like ptarmigan. According to Hicks, an archeologist at City of New York College, they preferred the eggs, which became much more important during the nesting season. “It was a very marked aspect of people’s lives in Myvatn. They were just eating so many eggs.”

But how to make sure they didn’t eat too many? That’s where the harvest rules come in — a set of customs practiced today and attested from century-old mentions in law codes, diaries and oral tradition.

Hicks listed them out. First, hunt foxes to keep predation of waterbirds down. Second, during the breeding season, collect no more than half the eggs from any waterbird nesting on your stretch of lakeshore. (Ducks won’t notice the loss of a couple of eggs, but it’s extremely easy to permanently scare waterfowl away from a nesting site, Hicks said.)

Icelandic farmers also tended to create infrastructure for hole-nesting ducks like the barrows goldeneye — ”locally abundant, but extremely rare in other places,” Einarsson said — which happily made use of stone walls or nesting hutches, and learned to live with losing a few eggs a season to the farmers.

How far back do these rules stretch? It’s hard to say for sure, but the team suggests that the presence of ancient eggshells — along with the general absence of waterfowl in the cooking pot and Myvatn’s continued diversity of waterfowl — may link these customs back to the first settlement at Skútustaðir, around 900 years ago.

“Finding only an occasional duck bone, but a lot of domestic animal bones, tells you that the people were only going for the eggs and not hunting the birds,” Einarsson said. “This is just like today, and supports the notion that the present day egg harvest is based on a very, very long tradition.”

“Basically, people were preventing waterfowl from abandoning their micro-landscape as a breeding area — but the landscape effect is that waterfowl never abandoned the region,” Hicks said. “So what we have is still a really healthy and biodiverse ecosystem.”

There is a notion you sometimes see floating around that any human usage of animals is ultimately damaging. It's understandable why people used to a particular exploitative capitalist mode would think this way: it's a mindset that encourages us to think of ourselves as divorced from nature, and as the natural world simply a set of resources to be extracted. And it's certainly true that unrestricted hunting, an unfettered commercial trade, and our modern buzz-saw of a built environment can have nasty effects on the creatures around us.

But these are ultimately expressions of a broader fact: that we have long-standing relationships with our animal neighbors. Some of those relationships are incredibly deep and intimate, as with domesticated animals like chickens and ducks. Some, as with the birds hunted for feathers, are overtly predatory. Some are difficult to put a name to — the strange recognition between us and the crows, grackles, jays, and other songbirds that flit at the margins of our societies.

As the above stories show, there are many ways to use, manage and cooperate with birds. Many of them have been practiced quite comfortably for far longer than our current societal setup would suggest. Which means that unthinking, relentless domination of our avian neighbors is not an innate aspect of human biology. We take from them, and can give back to them. We shape them, and are shaped by them. It's a millennia-old dance, recorded in stories: tales of when birds were people, and people were birds, and the line between them seemed as soft and yielding as a feather.

Or, as songwriter Laura Marling once put it:

Perhaps I'll be a bird one day

If I'm good enough

And I'll spread out and fly away

And give up all this stuff...

That's Heat Death, everybody. We'll be back soon with more interviews, essays and musings on past, future, and all the crises in between. If you enjoy our work, don't forget to subscribe!

Member discussion