The Soul In The Machine

Picture an artificial person. It does the drudge work that no living person wishes to do, or the dangerous work that no living person can do. It has no great will of its own, moving only as commanded, setting about its tasks without fuss, without complaint, without inconvenient requests for "better treatment," or "time off," or even – perish the thought! – "wages."

It can be as human-shaped as you desire, as inhuman as wished. It can walk your dog for you. It can make your vehicle, or be your vehicle. You can take it to bed, if that's your fancy, or break it, or mistreat it, or simply set it to a task and never think of it again. Why not? It's artificial. Isn't it?

There have been states – many of them – that ran largely on the backs of this sort of labor. The vast plantations and public works of Republican Rome were tilled and turned and built by the hands of such not-people, enslaved in wars of conquest and set to work. The slave-lords of the American South – who fancied themselves a new Roman Aristocracy – recreated that brutal system in the Southeastern United States, slapping on ever more restrictions, ever more layers of not-humanity, until they could not conceive of those workers as anything but animate tools.

This is, of course, a dream of slavery. But look into the eyes of these not-people, fashioned in chrome, in electrodes, in lab-grown meat and synthetic organics. Stare long enough, and you might recall that there is no fantasy of ownership that does not carry with it – like a long shadow, like a cold wake, like the burn of acid in the throat after too rich a meal – the terror of a reckoning at its end.

Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that knows that humanity is as humanity does. Despite our mutual affection for science fiction in general and stories of robot consciousness in particular, we're pretty AI skeptical over here at headquarters, and have been contemplating the grandiose claims of the industry – and its ever-increasing attempts to outsource ever-more human tasks – with mounting displeasure.

We were delighted, therefore, to hear from J.D Harlock, an American writer and academic who works – appropriately enough – at Android Press as an editor. His writing has been featured in Strange Horizons, New York University’s Library of Arabic Literature, and the British Council’s Voices Magazine.

He's come on to poke at the whole question of robots and automation from a different angle than you usually see. To strip away decades of accumulated storytelling, and see what thematic gears are turning underneath, and to ask a deceptively simple question: what is a robot, really?

It's Heat Death. Stay with us.

The Forgotten Origin of the Word "Robot"

J.D here. Whether they’re called automatons, droids, or animatronics, robots have been a standard trope for over a century, with variations depicting them as everything from slavish sidekicks to potential lovers. But they’re most prevalent, of course, as killer machines bent on rising up, overthrowing humanity and seeking world domination.

The robotic revolt is ubiquitous in popular culture. But few realize that this idea goes back to the very roots of literary depictions of robots. As we plunge ever deeper into an age of destabilizing automation — one that anxious science fiction visionaries long foretold — it’s time to go back to the source of those ideas, and see whether they can reshape our understanding of humanity.

But first, the visionary. Karel Čapek, a Bohemian writer — and editor, playwright, critic, journalist, and philosopher — was considered one of the preeminent voices of Czech literature in the early 20th century. Internationally renowned and nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature a grand total of seven times, Čapek wrote numerous politically charged works that dealt with the social turmoil of his era. Yet today, he is mainly remembered for the play R.U.R., which introduced two major concepts that would become staples of robot literature: the word “robot” itself, and the idea of a robot rebellion.

“Robot” wasn’t Čapek’s first choice for naming the artificial beings. Čapek had first wanted to call the creatures “laboři” from the Latin “labor,” meaning workers. But — unsatisfied with the term — he consulted his brother and lifelong collaborator, writer and painter Josef Čapek. Josef suggested roboti. The word has deep resonances in the Slavic languages that aren’t immediately obvious in English — overtones which carry with them the implicit tensions of slavery or semi-slavery. In Czech, the word “robota” refers to the period a serf (corvée) had to work for his lord, and it originated from the Old Church Slavonic “rabota,” (работа) meaning “servitude.”

This reference wasn’t just a nod to robots as a tool of automation. In R.U.R., robots are artificially created beings designed to perform labor for humans, and the story explores the consequences of creating artificial life forms to serve such needs. In turn, the titular acronym “R.U.R." stands for Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti, and it translates into Rossum's Universal Robots — the in-universe name of the factory that, in the play, produces artificial workers from synthetic organic matter.

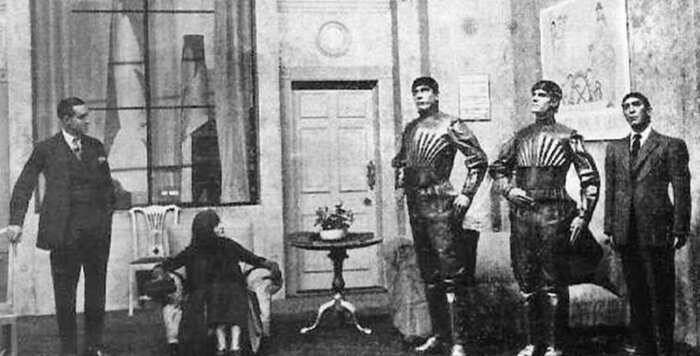

The fact that the roboti in R.U.R. are artificial workers from synthetic organic matter is an often-overlooked aspect of the play. Contrary to the inorganic constructs that we’re familiar with today — all shining chrome and metal chassis —the robots in R.U.R. are living creatures of artificial flesh and blood, like us. The founder of the factory, Old Rossum, views himself as a God-like figure, and although Čapek's roboti are biological beings, they aren’t born or nurtured, but put together — a clear reaction to Henry Ford’s contemporary popularization of the assembly line. They’re what we now call “Androids,” itself an old 1837 term for a man-shaped thing. Today, the word generally refers to something more then a mere machine, and the same is true of roboti. In the play, both the fact that they are essentially biological beings and the etymology of their name is meant to make it clear to the audience that they are, in fact, stand-ins for the 99%.

As a result, robots in R.U.R. are mistaken for humans even though they have no original thoughts, a feature of their programming which is intended to make them content in their servitude. But that feature ultimately makes them worthless as workers: because the roboti can’t feel pain, they’re prone to working even as they’re being injured — something they will do until they’re destroyed.

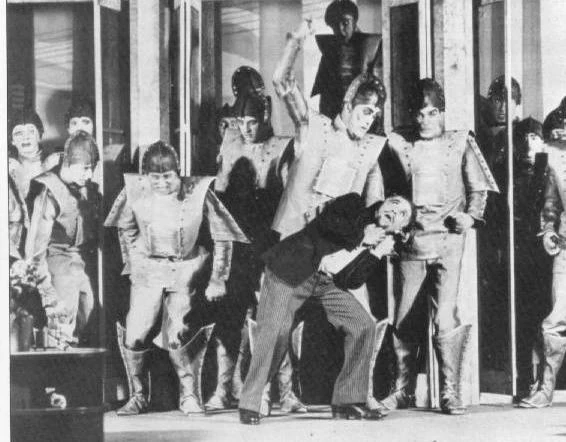

To remedy this quirk, the manufacturers introduce irritability into the roboti, which leads to them attaining consciousness. They come to resent their exploitation and their ultimate fate of being disposed of when their bodies break down. The resulting confrontation with their material circumstances leads solidarity pervading their ranks, and they launch a successful rebellion to wipe out their owners — with only one human, Alquist, allowed to live, because the roboti view him as a kindred spirit: he’s the only human at the factory who works with his hands.

The rebellion is an immediate success — but it doesn’t save the roboti from their fate. While they have succeeded in taking over the world, they are still doomed by design: their creators gave them a limited lifespan and made them unable to reproduce. The secret procedure to manufacture them was destroyed during their uprising, and the scientists who could recreate it have been killed. So the roboti desperately offer themselves up for dissection by Alquist so that he may learn how they are made — but Alquist is not a scientist, and his futile attempts are in vain.

Having lost hope in the future of mankind as well as the roboti, Alquist is on the brink of despair when he encounters two young roboti, Primus and Helena, whose behaviour could be construed as strange when compared to others of their kind due to their unusual devotion to each other, which neither can quite explain. Realizing that the mechanical nature of this pair has undergone a remarkable transformation, Alquist makes the religious undertones that have been lurking in the play more explicit: he invokes the biblical narrative of creation, instructing them to proceed as the new Adam and Eve, consoled that life does not end with his death.

R.U.R. was Čapek’s first dramatic work to be translated from Czech and produced abroad, and while it was well-received, Čapek was disappointed in the simplistic critical reaction. Reviewers tended to read it as a retread of the genre-defining Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. Or as an anti-capitalist satire. Or as a topical denunciation of contemporary political ideologies.

But Čapek intended R.U.R as something more: a statement of faith in human survival, even in a world where humans like himself have been driven to extinction. Despite that deep sense of optimism, and the miracle that culminates the play, it is largely remembered as pessimistic or even nihilistic. Some critics believed that flaws within the play — particularly structural pacing issues and abrupt tonal shifts that rework the premise in the process — led to a misunderstanding of R.U.R.’s thematic ambitions.

That may be true to a certain extent. But a significantly overlooked factor in the play’s interpretation in the English-speaking world is its first English translation by Paul Selver. Even though it wasn’t faithful to the original version of the play, early English productions were based on it, and it was subsequently published in the United States and the United Kingdom, and has been included in anthologies for decades.

Among its numerous substantial changes to the text, the final lines of the play were extensively cut down when it was first translated. The final scene has Alquist press the robots Primus and Helena for an explanation of what he suspects is happening between them, after they resist his attempts to dissect them. In Selver's version — the only version any English-speakers read for most of the 20th Century — he only responds with:

PRIMUS: We-we-belong to each other.

ALQUIST (almost in tears): Go, Adam. Go, Eve. The world is yours.

(Helena and Primus embrace and go off arm in arm as the curtain falls.)

It wasn’t until 1981 when Mary Anne Fox published a research article with a much more complete translation of the final lines of the play, one that reveals a much more fleshed-out ending and makes Čapek’s point in R.U.R. clearer.

After Alquist tells Primus and Helena to go, he is left alone, and begins to speak.

ALQUIST (alone now): Blessed day!

(He tiptoes to the table and pours the contents of a test tube on the floor.) Holy sixth day!

(He sits down at the writing desk, tosses the books there to the floor; then he opens a Bible, leafs through it, and reads:) "So God created man in His own image, in the image of God created He him, male and female created He them. And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth."

(He rises.) "And God saw everything that He had made, and behold, it was very good. And the evening and the morning were the sixth day."

(He goes to the center of the room.) The sixth day! Day of grace! (He falls to his knees.) Now, Lord, dismiss your servant, your most useless servant, Alquist! Rossum, Fabry, Gall, you great inventors, what great thing have you produced to compare with this first pair who have invented love, weeping, laughter, the smile, the smile of love, the love of man and woman? Nature, nature, life will not perish! God, life will not perish! Comrades, Helena's life will not perish! It will begin anew, begin from love, begin naked and small; it will take root in emptiness, and all we have done or built will be for nothing, our cities and factories for nothing, our art for nothing, our ideas for nothing, but still it will not perish!

Only we shall have died. Houses and machines will decay, our systems will fall apart, and the names of the great ones will wither like the leaves; only you, love, will blossom on the ruins and cast the seeds of life to the wind. Now, Lord, dismiss your servant in peace; I have seen with my eyes your salvation by love, and life will not perish!

(He rises.) It will not perish! (He stretches out his hands.) It will not perish!

R.U.R. cautions against our relentless pursuit of technological progress as it relates to commercialized automation — the roboti render humans superfluous except for their role as consumers, inadvertently leading to their extinction.

However, the symbolism of the roboti shifts throughout the play, for they are much more than monsters that turn upon their makers (as was perceived to be the case with Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.) They represent the common man as he exists in industrial society. In this sense, R.U.R. is about what humans have to become if they wish to liberate themselves from systems established in mindless devotion to false progress, which invariably fuel greed, authoritarianism, and national hatreds — as well as the creation of a resentful, potential violent class of laboring serfs.

Čapek hoped to use the plot device of a robot rebellion to show that humanity can survive the existential catastrophes we’ve wrought on ourselves, so long as its fundamental qualities are preserved and transmitted — even if not in its current corporeal form. To Čapek, these fundamental qualities are a feeling of joyful being, spiritual growth, and the ability to love and be loved, which have been diminished in an industrialized society for humans and roboti alike. Nowhere is this better exemplified in the play than by the factory’s overseers, practically the only humans present in the play, who have no ambitions beyond maximizing shareholder value and are unconcerned with the sociopolitical and economic impact of their work — an obsession that makes them appear even more robotic than the roboti they manufacture.

Consequently, as the play reaches its tragic conclusion, it becomes clear to the audience that this form of dehumanization – perpetuated by ourselves through our relentless automation – was the true extinction of humanity, which inevitably culminated in its physical destruction.

Today, of course, anxieties around automation have returned to the forefront of public discourse. Current trends like the widespread industrial adoption of Large Language Models like ChatGPT and Midjourney have begun to fundamentally change life as we know it. Prior to their introduction, automation served to reduce the demand for certain professions, or, at worst, render specific fields – the human calculator, the assembly line worker – obsolete. This had a terrible effect on countless lives, but it didn’t threaten to reshape our collective human experience. Now, “generative AI” is accelerating our collective, en masse transition from people who both make and consume things to people who only consume. People whose only role is to keep an eye on the relentlessly inhumane instruments usurping parts of our lives.

Many of those experiencing R.U.R may find themselves uncomfortably relating to those factory overseers — whose modern form are the knowledge workers who increasingly spend their time watching AI instruments do their job.

We must take what Čapek says to heart. We must take back control of the reins of progress from our techno-feudalist overlords in Silicon Valley — who, like Old Rossum, think of themselves as something like gods — and steer this automation in a compassionate direction. One that considers humanity above all else. One where the wealth realized with this technological advancement is redistributed through social services that help communities, and preserve the qualities essential for humanity to survive, persevere, and thrive in the future.

It is important — now more than ever — to empathize with the roboti. Their struggles is our struggle, and, though it may seem bleak at first, in their salvation is ours.

J. D. Harlock is an Eisner Award-nominated American writer, researcher, editor, and academic pursuing a doctoral degree at the University of St. Andrews, whose writing has been featured in Strange Horizons, Nightmare Magazine, The Griffith Review, Queen’s Quarterly, and New York University's Library of Arabic Literature. You can find him on Bluesky, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, & Twitter.

This has been Heat Death! This piece was supported by paid memberships to this newsletter. If you'd like to support us – and help us commission more work like this – please consider grabbing a subscription. Want to pitch us? Send ideas to aelbein@gmail.com.

We'll be back soon with more musings on past, future, and all the crises in between. Take us out, little critters.

Member discussion