The Species Problem

Here’s a question for you to ponder, dear readers: what, if anything, is a species?

Well, you might reasonably say: humans are a species. Wolves are a species. Domestic horses are a species, as are great-tailed grackles, tyrant flycatchers, oaks, Texas rat snakes, bluebonnets, and any other sort of animal you can imagine. If you remember your high school classes, you might say that a species is any population of animals that doesn’t—or can’t—interbreed with related species.

Of course, you’re one of our readers, so you’re clever enough to know that when an article leads off with a question like that, the answer’s unlikely to be anything so simple.

Asher here. Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that has its knees all scraped-up from climbing phylogenetic trees. On Tuesday, I had a feature run in the science section of The New York Times about a controversial proposal by a team of researchers: that the famed, iconic dinosaur Tyrannosaurus rex is not one, but three different species, all of which had been hiding out under the same name. Plenty of experts disagree with the finding--and say such a claim requires a lot more proof.

It’s a fun story, and you can go read it right here.

But beyond the headline grabbing claims, it raises some pretty interesting practical and philosophical questions about how we separating out different species. It draws attention, in fact, to one of my favorite issues that non-biologists are happily ignorant of: that the concept of “species” fairly arbitrary, and there’s absolutely no universal agreement for what counts.

It’s called, in some quarters, the species problem.

Let’s start simply, with a quick reminder. Under the Linnaean system, scientific names are split between genus and species. Genuses—like Panthera, or big cats—are the box that holds a number of distinct species, like lions, tigers and leopards. Species, on the other hand, are a label that taxonomists apply to a specific sort of animal. (i.e Panthera leo, or lions, are distinct from Panthera tigris, tigers.)

But how do you define that distinction? Do you do it anatomically? That seems easy enough—lions and tigers look quite different. They also live—generally speaking—in different places. But telling them apart via bones would be quite a bit tougher, given their similar anatomical traits. Well, they don’t commonly interbreed. But as it happens, they can do so, producing the fearsome liger, which is a real and occasionally fertile animal that can be crossed back into either species.

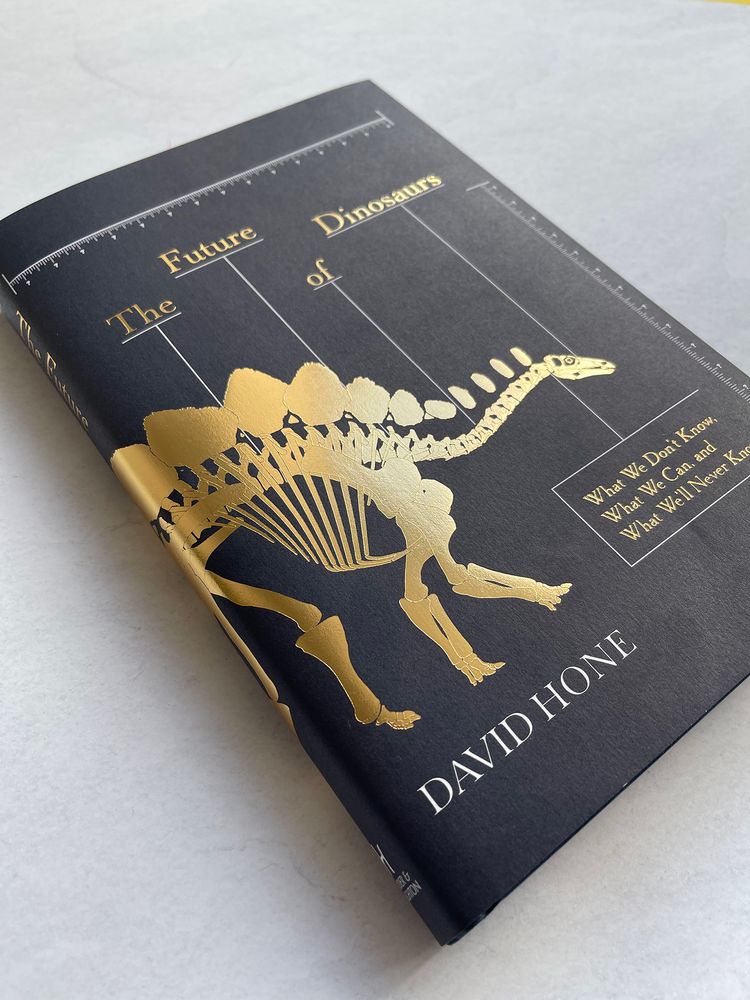

According to the biological species concept you learned in highschool, this isn’t supposed to happen. But according to Dave Hone, a a paleontologist at Queen Mary University of London, the classic high school biology definition of “species” — that it’s nothing more than a pool of organisms that can all interbreed and produce fertile offspring —is “a joke. I wish they didn't teach it in schools, because it's so hilariously inappropriate."

Why? For one thing, it leaves out organisms that reproduce asexually, of which there are quite a few. For another, it completely fails to account for the ability of many plants and fungi to hybridize and swap genes around. It also simply cannot be usefully applied to fossils, which make up 99% of all life ever to live on earth. There is absolutely no way to tell which fossil populations interbred—or didn’t—with one another.

But let’s ignore fossils for a moment. (Likewise, let’s dismiss the notoriously protean kingdoms of plant and fungi, and focus on the organisms that seem most easily categorized: living animals.) Surely the concept of biological species must have some value. What about genetics, which have revolutionized animal taxonomy? Could a species be a population of animals who are, to a certain degree, genetically distinct?

There’s something to this, as it happens: genetics are handy for parsing out animal populations and lineages that don’t generally interbreed with one another, even when they look quite remarkably similar—giraffes are a classic example, with Africa hosting four separate species, not one, or multiple “cryptic” species of killer whales that seldom mix.

But increasing genetic evidence also shows that quite a lot of animals we traditionally think of as different species can and do interbreed at the edges of their range. Rat snakes on the east coast and west coast have traditionally been considered different species, but most rat snake populations hybridize easily, and do so in a daisy chain right across the continent. Nor are they alone: hybridization can drive the development of new populations, such as polar bear/grizzly hybrids, which then either diverge or are swallowed up by neighboring ones. (And, of course, there are those pesky ligers.) Genetics work tells us that species are animals that don’t interbreed—except, of course, when they do.

That seems vague and not particularly useful. Let’s consider another possibility: that animal species are those with recognizable differences—that have different anatomical traits in terms of color, musculature, skeleton, or what have you. This is actually the old species model, and it’s still fairly useful. (Consider a bird field guide, with plate illustrations setting out the different species that come to your bird feeder, which have different coloration, sizes, and shapes.) You figure out a list of anatomical traits that broadly differ from one population to another, and boom, that’s a species.

But how many traits are required to set a species apart? What about species that all interbreed but show a lot of individual variation, like Homo sapiens—and, quite likely, archaic hominids we seem to have hybridized with? Here’s where we hit the other problem with morphological traits: every field—whether that’s lizard researchers, bird researchers, those studying fossil ammonites or those looking at bacteria—has a different standard for the kinds of differences they’re looking for, and all have jerry-rigged species concepts to match.

"There's no single definition for what a species is,” Hone says. In fact, he pointed out, there are something like 26 species concepts in the scientific literature, only half of which are regularly used, and many of which flatly do not apply to multiple groups. “Imagine trying to come up with a consistent standard for comparing T.rex to bacteria to asexually reproducing fish and domestic dogs. It can't be done.”

Nonetheless, species are useful as a way of ordering nature, so everybody basically does their best to get by, Hone says. “Defining species is always going to be somewhat subjective. Generally we have consensus within groups, but not between them. Beetle genera commonly have 50-100 species, or even a thousand species. Dinosaurs, it's usually one. And that's because different taxonomists are working to different conventions."

Now let’s go back to the question of fossil species, which is where things get both simpler and more headache inducing. Say you find a reasonably complete dinosaur skeleton—we’ll be generous and say that it’s about 70 percent intact, which is absurdly good. It’s an animal known from other, scrappier fossils from other, relatively contemporary deposits, but it shows some differences, too. Are you looking at a new species?

The question of whether or not this animal interbred with those other, scrappier individuals is closed forever. Genetic differences, likewise. Color and soft-tissue variation—i.e a lion’’s mane, a tiger’s stripes—are out, too. “Most of the things we would use in a bird identification guide are soft tissue features that we would never be able to tell,” says Tom Holtz, a paleontologist at the University of Maryland. “Color or sound pattern? These guys are totally silent now, and they're the color of whatever the fossil bone is. We don't even see if there are crests or wattles or things like that."

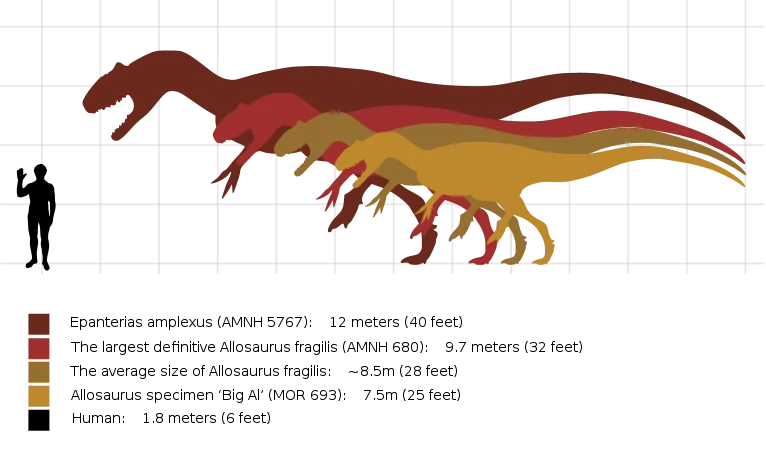

All that’s present to work with, in other words, is the anatomy of the bones themselves. This can be quite useful, but also tricky—some dinosaurs seem to have changed a good deal as they aged, and individual variation always has to be taken into account. (How do you know, for example, that what you think is an Allosaurus maximus isn’t just a particularly large Allosaurus fragilis?)

“Most dinosaur species are known from a single fossil, tooth [or] a single point on the axial skeleton,” says Leonard Finkelman, a philosopher of paleontology at the University of Oregon. As a result, species labels are generally applied as a description for a snapshot in geological time: sometimes you’re lucky enough, as with the various species of Triceratops, to be able to trace distinct changes emerging over a million years or so. Other times, you can find an animal that looks one way early in a formation, and another way a few million years later, with a handy break in the record in between.

Here’s the other useful thing to note: even within dinosaurs, the standards for what it takes to designate a new species—or genus, for that matter—are notoriously tough to pin down, and liable to fluctuate according to the level of evidence you’re working with. If you’re working with an obscure animal that has relatively scrappy remains, species distinctions based on one or two anatomical differences often stand. But if you’re working with popular and better studied animal, differentiating species gets harder. In part, that’s because more extinct animal remains can make it harder it can be to suss out species differences, because the amount of individual variation is necessarily higher. As a result, specialists generally demand higher standards of proof.

If this sounds like dinosaur species are assigned based entirely on vibes, well, that’s partially right. But it’s more accurate to say that in dinosaurs, “species” as a concept works primarily to track anatomical differences across vast sweeps of time and location. The trouble, Finkelman says, is that nobody has ever tried to set a consistent standard for the minimum number of unique anatomical traits that officially make a new species. The International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants does have such a standard for fossil taxa, as it happens. The utility of such a standard lies in admitting that for fossils, the notion of “species” is essentially a filing system for ease of research. It’s not something that closely matches any sort of biological species concept, which—you will recall—only intermittently works, anyway.

Summing up, then: How do we apply species concepts to extinct animals? Subjectively. How consistent are those concepts? Not very! How much evidence is required to split some animals, and not others? Depends!

All of which leads to perhaps the most useful species definition: the taxonomic species model, wherein a species can be summed up essentially as “whatever experts say it is.” In essence, if the vast majority of specialists agree that something is different enough to be called a species, then that’s enough, because “species” is ultimately a largely subjective and artificial distinction, anyway, and we might as well get on to the bar before it closes.

Rather than being an iron-clad bit of filing, calling something a species is essentially making an argument: this thing is different from this other thing at this point in time. But, of course, populations flow and split and remeld over thousands and millions of years. Sometimes they interbreed, and sometimes they don’t, and the importance of such differences to species themselves differs hugely across the vast diversity of life. Or, as Hone puts it: “biological reality doesn't care what taxonomists say is a different species.”

All of this is, by necessity, somewhat chaotic. But life on earth is chaotic—gloriously so. The sooner everybody gives up the notion that species are real, the more useful the concept will be.

This has been Heat Death. If you'd like to support the newsletter, you can grab a paid membership for just 5$ a month, or keep enjoying our free offerings by signing up right here.

Member discussion