The Suburbs Sprawl on a Grave of Wildfire

Saul here. When I was in high school I came home one afternoon to find an angry snapping turtle on our suburban lawn. Its jaws open in a silent bellow of saurian rage, it glared at the world — and specifically at Asher, whose fault it was.

This was less unusual than it might have sounded: Asher, then in middle school, spent his afternoons running the creek by our house in the sprawl of North Dallas, bringing home stories of unexpected animals — like the beavers he always swore were in a pond in some bit of edge forest upstream — or the animals themselves: turtles, Western fence lizards, one time a skunk.

Our parents had made their peace with this by instituting a maximum stay for these captives: three days and they had to go back to wherever Asher had found them. And it was under this accepted rule that Asher, having pulled the snapping turtle a couple of hours prior from the muck where it was minding its own business, had stashed it in his bathtub. Until, that is, our mother, hearing something rustling, opened the shower curtain and let out a scream that, I am told, broke windows three streets down.

The snapping turtle had to go. So that night — Asher having secured a stay of a few hours — we walked it down the street, me holding it while it strained its shockingly long neck back to bite at my fingers, Asher (for some reason) holding a flashlight in its eyes, until we came to the creek from which it had been so unceremoniously yanked.

This is Heat Death, the newsletter that is not afraid of a little sprawl as a treat. I bring up this bit of Brothers Elbein lore by way of introducing today's essay, from journalist Marin Scotten, which dives into the surprising roots of the American suburb in a now-failing attempt to control nature.

In it, she lays out the surprising parallel evolution of two developmental cousins: the suburb and the managed forest — which are both, in today's America and increasingly in the world, becoming the dominant forms of technocratic landscape you may encounter.

This is, in historical terms, a staggering change. Both suburb and forest come from Latin juridical words, and until about 150 years ago neither described the kind of place they now seem to. Suburb meant developments outside the city walls; forests, a contraction of the Medieval Latin forestis sylva, meant the land outside communal or private jurisdiction that was the domain of the King and, later, the state — which is to say, a juridical category that meant not a group of trees (bogs, swamps and heath were also "forest) but the land, broadly, "out there," where foraging blended into the crime of "poaching."

Which is to say, for much of the history of Western development, both suburb and forest were marked by what they weren't: regulated, intensively managed or the domain of normal people.

And then, about 150 years ago, something decisive changed — as central governments began to go to war against a particular form of danger and disorder present in the forests that lurked on the edges of farms and cities: fire. Marin tells the story of how that crusade cleared the ground for the suburbs, and for the agonies to come.

But also, it suggests a way forward — the reality hinted by that snapping turtle: that even excluded, nature finds its way in. The creek by our North Dallas house had enough fish for a snapping turtle; enough wildness, still, for a pair of young boys. Back on the grassy bank of my memory, in the darkness below where the oaks shaded the creek from the streetlights of Meandering Way, we set the snapping turtle on the bank and watched as it slipped into the black water below.

A reminder that there is no structure that, given enough time, life will not remake.

This is Heat Death. Stay with us.

Heat Death is an entirely reader-supported newsletter, and all proceeds go toward paying guest writers and maintaining our web-hosting.

If you enjoy what we do here, please leave us a tip or sign up: paid subscriptions are just $2-$5 a month.

How Fire Suppression Built the Suburbs

Marin here. Growing up, I loved suburbia — the uniformity of the houses, the backyard pools, the smell of freshly mowed grass and hotdogs cooking on the barbecue. For a terribly anxious child who could barely leave her mother’s side, the predictability of my surroundings brought me peace. I even remember feeling bad for kids who weren’t growing up in the suburbs, pondering how hard life must be in a gritty city. (I’ll add that I grew up in Canada, and the city in question is Ottawa, a quiet government city with a population just over one million and very little grit to be found.)

I don’t remember the exact moment when the glass shattered for me and the sameness of suburbia started to get under my skin. I think I was in middle school, just starting to develop critical thinking skills, when I started to ask: Why did all our houses look the same? Who decided it looked cool to plant one single tree in everyone’s front yard? Or that strip malls would be a fun place for teenagers to hang out? I declared this suffocating, car-infested place was holding me back from my dreams, and the controlled environment that once soothed my anxiety quickly became the source of it.

My tweenage revelation was nothing novel. Most kids decide they hate their hometown at some point in their lives. But everything I was feeling — isolated, bored, sheltered from the outside world — came about because that’s exactly what suburbia was designed to be: a carefully crafted refuge free from inconvenience and disorder. The suburbs were marketed to middle-class white people as a retreat from the chaos of ever-expanding urban centers (and the low-income people who lived there), with the illusion of a safe, well-maintained landscape as their backyard.

It’s an ideal sold on privacy, safety, and control over one’s surroundings. And one that stemmed from the attempt to control one of nature’s most powerful forces: fire.

In early 19th century Prussia (now part of modern-day Germany), forests were vital to peasant life. Not only were they abundant with materials for building, food, and medicine, but they were places of gathering and worship — a space central to peasant identity. But as the Prussian kingdom grew in population, it also sought to expand its infrastructure. State authorities knew the economic potential of timber, and trees quickly became economic resources to be measured, sold and replicated. As James C. Scott recounts in the book Seeing Like a State, German foresters tagged trees with color-coated nails based on size to estimate the timber value of the entire forest. The forest was reduced only to what was economically valuable, and everything else — flora, fauna, insects, wildlife — was deemed useless. Gone was anything that did not serve a commodified purpose. What remained was a narrow slice of the ecologically diverse, interdependent ecosystem that had sustained communities for generations.

Armed with a meticulous measurement system, forest managers replicated their methods across the region, altering the delicate functioning of thousand-year-old forests. They planted trees in single-line neat rows, all to be tracked, measured, and sold. They reduced the forest’s value to its revenue as timber yield, and by extension, what that timber could do for the state. Anything that jeopardized said revenue — local needs, public access, and the natural process of fire — was considered a threat. It was a utilitarian approach to forest management, and one that, as Scott points out, required totalitarian control.

Scott writes:

The German forest became the archetype for imposing on disorderly nature the neatly arranged constructs of science. Practical goals had encouraged mathematical utilitarianism, which seemed, in turn, to promote geometric perfection as the outward sign of the well-managed forest; in turn the rationally ordered arrangement of trees offered new possibilities for controlling nature.”

In ecological terms, the experiment was a disaster. Within a century, single-species forests were struggling to survive. The complex, interdependent ecosystems that previously consisted of diverse flora and fauna, fungi, insects, underbrush, all of which were essential to the soil-building process and pest-resilience, were entirely disrupted. Trees — which in the new German forest now stood alone — depend on other species, and each other, to thrive. Scientists have identified specific compounds that one tree will release when it’s under threat to warn other trees of danger. Other trees sense those compounds and know to release defensive chemicals to protect themselves. Much of this communication between trees happens underground through networks of mycorrhizae, a symbiotic connection between plant roots and soil fungi, connecting the multitude of trees in a forest and helping them share nutrients with each other. To isolate trees into a singular unit, and then build an entire forest of those individual units, is to cut them off from what they needed to thrive. What remains is not really a forest at all.

But economically, German forest management brought reliable profit, and it was solidified as a system that successfully turned “nature,” which encompasses the entire natural world (forests, oceans, animals, rain, sunlight, fire) into a “natural resource,” an individual natural element that can be extracted and utilized by people.

It’s a dynamic that would come to define the Western world’s approach to conservation for generations. Foresters from around the world went to Western Europe to study the new method, including one young Gifford Pinchot, the son of merchants and landowners from Connecticut whose family fortune came primarily from selling timber— commodifying nature was in his blood. Pinchot spent several years studying German forestry management in Europe, and returned to the United States with a novel vision for how to conserve the 800 million acres of American woodland, which up until that point were managed locally, not by a collective federal agency. In that period, forests were being logged by private companies more than ever before, and there was little to no regulation on clearcutting or replanting trees. Inspired by his studies, Pinchot was the first to advocate for the protection of forests from private logging, and to suggest they be managed by a governing body.

But his vision for conservation was not to protect forests as part of nature. It was to preserve the goldmine of timber, a natural resource essential to American prosperity.

In his book The Fight for Conservation, Pinchot writes that:

The first principle of conservation is development, the use of the natural resources now existing on this continent for the benefit of the people who live here now.

In Pinchot’s view, the primary reason for protecting forests was so people could benefit from their wood. As in Prussia, if a certain element did not have potential as a human resource, it was deemed useless. Gone was the forest’s vast array of other uses for hunting and gathering, fishing, socializing and worship, as was common in Indigenous communities across the world. This bleak and simplistic view of nature caught on quickly. In 1905, Pinchot was named the first chief of Theodore Roosevelt’s newly created U.S. Forest Service, and he, along with several other early Forest Service architects, set out to redesign American woodlands to maximize long-term timber yield and minimize loss from pests, disease and fire. Vast stretches of diverse forests were replaced with fast-growing, commercially valuable species like White Pine, Douglas Fir and Loblolly Pine. Trees became capital to be protected at all costs.

Specifically, it was to be protected from fire.

Most of us were taught in grade school that fire, no matter where, when or how it burns, is dangerous. It’s destructive, uncontrollable and serves little purpose outside cooking and heating, where it is neatly contained. But before the 20th century, fire wasn’t always seen as a bad thing. For millennia, Indigenous communities used fire as a forest management tool, it too was part of the interdependent ecosystem that kept a forest healthy. Hundreds of tribes across California, including the Yurok, Karuk, Hupa and Miwok, used small, deliberate burns to clear highly flammable brush from the forest floor, reducing the risk of destructive wildfire. The practice, known to many Indigenous tribes, as “good fire,” decreased forest density and opened the forest canopy, creating new opportunities for vegetation to grow. Good fire provided food, medicinal and cultural resources, and it is central to many tribes’ culture and identity. Bill Tripp, the Director of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy for the Karuk Tribe refers to fire as a “vital, life-giving force,” and says cultural burning is a solution rooted “in relationship, reciprocity, and resilience.”

He adds that

When we light fire on the land, we are exercising our inherent rights to manage our territories according to our laws, values, and relationships. Fire is a teacher, a relative, and a force for healing.”

But to the U.S. government and its agencies, fire was not a tool for stewardship, but a threat.

In 1850, California banned cultural burning as part of Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, an ironically named piece of legislation designed to forcibly remove Indigenous people from their ancestral land and effectively enslave them. Similar bans on cultural burning passed across the country, and was ultimately enshrined federally by the Forest Service, which adopted a strong anti-fire stance through policy and public messaging. This was bolstered by the Great Fire of 1910, a devastating wildfire that tore across Northern Idaho and Western Montana, burning through more than three million acres of land, flattened entire towns and killed 87 people. It was the country’s most disastrous wildfire to date, and it confirmed to the new managers of the nation’s public lands that fire was destructive not only to American forests, but to human life and livelihoods.

Total suppression, they deemed, was the only option.

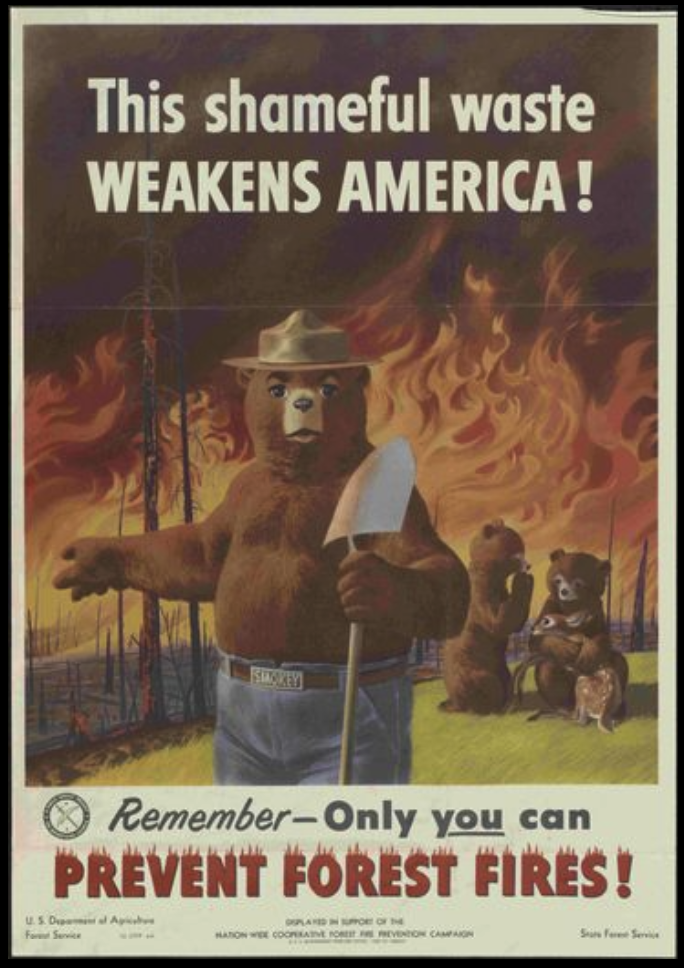

Within months after the Great Fire, the Forest Service declared that all fires could and would be prevented. All it would take is more money, more men, and more grit. By mid-century, federal law codified aggressive fire suppression through various policies: The Weeks Act of 1911 allowed the Forest Service to implement fire suppression strategies on state and private land; the ”10 a.m. policy” of 1935 sought to extinguish all fires by 10 am the next day; and the message that “only YOU can prevent wildfires,” was publicized widely by Smokey the Bear, the mascot of the U.S. Forest Service.

All of this solidified the militarized approach to fighting fire that preserved timber yields for a generation — but that has proven, over the long term, to be disastrous to the North American landscape. Without prescribed burns, landscapes were primed for more destructive wildfires. Dead plants and highly flammable brush accumulated on forest floors, and grass and shrub grew out of control. Giant sequoia, which rely on fire in their lifecycle, stopped growing — a discovery that eventually led to the re-implementation of occasional prescribed burns in 1968. Since then, a number of states have implemented prescribed burning into the forest management strategies. (And some in the Southeastern U.S. never stopped.)

This was a step in the right direction, but it was too little too late. By mid-century, fire in all its forms was already an object of fear.

In January 2025, six separate wildfires simultaneously blazed through parts of Los Angeles. Spurred by hurricane-like winds reaching almost 100 mph, the flames killed 31 people and destroyed more than 16,000 structures and homes.

But when we say that the fires burned Los Angeles, we should be more precise. The majority of the homes that burned were built on what’s known as the wildland-urban interface (WUI): a zone of transition between wilderness and land developed by human activity. From the 1950s onwards, the federal policy of fire-suppression made high-risk, flammable wildlands temporarily safe for housing development, and millions of homes sprawled into the WUI as the U.S. government simultaneously sought to shift housing from urban centers to new suburban developments post-WWII.

This expansion was ideological as well as policy driven: The campaign of fire suppression rested on and reinforced the idea that nature could be controlled, and that land managers could alter wildlands at will to serve their needs. In this model, natural landscapes, historically unpredictable and dangerous, were no longer something to be feared, but something that could be contained with will-power and determination.

This was the perfect message to sell a future built on privacy, control and ownership over one’s space. Which is to say: the suburbs.

In fact, home ownership in new housing tracts was a key part of Pinchot’s plan. In The Fight for Conservation, he wrote that:

The single object of the public land system of the United States … is the making and maintenance of prosperous homes. That object cannot be achieved unless such public lands as are suitable for settlement are conserved for the actual home-maker.”

In other words, the point of protecting land was so that people had space to live out the American dream. Controlling the forest and all its elements — fire included — was a crucial first step in instilling confidence in a free, enterprising America, and it laid a foundation for a housing system designed to do the same.

Post-war, the lack of homes was so dire that in 1946, Congress declared the housing shortage a national emergency. With millions of veterans returning home and starting families, cities couldn’t keep up with the demand. The stakes were high: not only was accessible home ownership needed to house millions of people, but it was essential to keeping the public’s trust in the American political system. America’s political leaders worried that mass homelessness, particularly of the heroic veterans who just helped their country win a war, would corrode faith in America's global dominance.

“In no sector of the national community has the erosion of mass confidence in democracy’s ability to get things done reached a more critical phase than in the home-building industry,” a 1946 Senate report reads. In other words: build more homes or risk political turmoil.

That was a risk the United States couldn’t afford as it sought to establish confidence in a capitalist system amidst a growing socialist movement worldwide. So the U.S. government made it easier for (white) people to buy homes. The Federal Housing Administration backed mortgages for suburban homes, but often refused to ensure mortgages in racially diverse, urban neighborhoods. Developers reproduced suburban neighborhoods en masse coast-to-coast, and the newly created interstate highway system connected these outer areas to city centers. Urban planners radically redesigned growing metro areas to favor sprawl over density, highways over transit, and separation over integration.

As a postwar institution, the suburbs promised privacy, space, good schools, and safety; a reserve for those who wanted a life free of perceived inconvenience, danger, or difference. The suburban family epitomized the American dream. The image of two kids, a car, and a white picket fence embedded itself in the zeitgeist as the ultimate marker of success.

And the package sold. Between 1945 and 1970, over 13 million homes were built in the suburbs. In the same time frame, America’s suburban population nearly doubled to 74 million, with 83 percent of all population growth occurring in suburban areas. With their quiet streets and fenced-in backyards, the suburbs became a sanctuary of sorts, where the messiness of the outside world ceased to exist.

But that same insulation that made me feel so protected as a child is also what makes suburbia feel empty. Just as the underbrush and fungi and pests were deemed unnecessary to forests and cleared from their grounds, suburbia is stripped of any form of connection nonessential to everyday urban life: passing strangers on the street, sitting in public space, walking to your local coffee shop or grocery store, unplanned social gatherings. Gone is the reciprocity with one's surroundings, the relationship to place and people that define both cities and small towns.

And just like the single-species forest that was its twin, isolation has led suburbia to decay over time as well. Today, more than 15 million suburban Americans live below the poverty line (about 8 percent of the suburban population), and a growing number of suburbs face aging infrastructure, higher crime rates, and increasingly unaffordable cost of living. Without any walkability or public transit, suburbanites are entirely dependent on cars, whose steel and tempered glass form another barrier to connection. They’re expensive too: keeping a car on average costs about $12,000 per year. The space suburbia advertised to its residents means everything is spread out, and low-density infrastructure requires more roads, more pipes, and more power lines to connect it all. All those spread-out utilities are expensive for local governments to maintain, particularly when so much less tax revenue comes in, given the fewer residents per square mile in comparison to a high-density, urban environment. (Not to mention the suburbs as the heart of the modern conservative revolt against property taxes).

In Disillusioned: Five Families and the Unraveling of America’s Suburbs, author Benjamin Herold argues that the vision of suburbia sold to white Americans post-war, and the “magical thinking that fueled its growth,” was doomed from the start. The heavily-subsidized construction of suburban neighborhoods that began in 1940 let people move in cheaply and quickly, with the promise of lower taxes, good public schools, and inexpensive mortgages. Concealed in that low cost was the fact that these neighborhoods were poorly planned, and the cost of maintaining and updating infrastructure was steep. In fear of racial integration, many neighborhoods refused to expand services like public transit that would have brought in revenue and benefit them economically, Herold points out.

That led to a kind of bleak analog to forest succession: by the time the neighborhoods started to crumble, most of its white residents had already moved to a bigger suburb built on newly developed land from farm or forest. And when working-class people of color eventually do move to suburbia, as they have in recent decades, the opportunities it once promised have long been drained by the people before them. It’s a never-ending cycle, and it will keep expanding until we run out of land.

It’s easy to frame the failure of suburbia as a simple opportunity for decision, the choice to collectively build a more reciprocal and resilient way of life. But most of us didn’t choose to live this way. We were influenced by forces beyond our control like policy, private profit, and cultural beliefs designed to make suburbia feel interchangeable with the American way of life. Truly redesigning how we live requires systemic change far beyond individual will.

While the policy changes needed to save both the natural environment and our homes remain largely out of our control as individuals, there is power in imagining something different despite this. On a communal level, change comes not from retreating further into isolation, it comes from connection — to people, to place, and to a collective future. By embracing the messiness that the managed forests and the suburbs were built to stifle, we may find the inspiration to build something new.

And we might remember that in a forest, when blight, changing climate and age have fatally damaged a forest’s key functions, fire clears space for new growth.

Marin is a freelance journalist who covers the intersection of climate, agriculture and politics. Her writing has appeared in The Guardian, The New Republic, Sierra Magazine, Salon, The New Lede, and more.

This has been Heat Death. We're entirely reader-supported independent media. If you like what we do here, feel free to subscribe: paid memberships are just $2 t0 $5 a month. (Or you can always leave us a tip.)

But while we're growing, the single most helpful thing you can do is send it to someone you think will like it or post it on your favorite social with a nice note. We are, above all, a word-of-mouth operation.

We'll be back soon with more musings on past, future, and all the crises in between. Until next time.

Member discussion