Seven Theses on Gehenna

There is a concept in Judaism called tikkun olam: It is the notion of "world repair," an idea that we live in a broken world, and that all things within it are thus, in their own ways, broken. Not fallen, mind, and not damned, as in various forms of Christianity—but imperfect.

In this world, there is suffering, and there is cruelty, and there are the ranks and cohorts of human weakness. These are the fractures in what might have been perfection, and was not. And it is the responsibility of those living in a world in need of repair to roll up their sleeves and clock in to help repair it.

Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that checks the plumbing of existence and offers you a quote. July 4th has come and gone; Saul made it down to the DC fireworks display, to have his nervous system pleasantly compressed by the concussions of colorful bombs going off above the reflecting pool and the cross section of Americans — young and aged, new and old — crowded below, speaking in Spanish and Portuguese and Russian and English. In Austin, grey clouds roll in ranks above the hills, dispensing much needed rain into a wildflower garden that looks much the worse for wear.

As always, the Brothers Elbein are busy about their appointed tasks. Asher has just returned from a visit to the San Antonio Zoo, where he delighted in learning about the facility's efforts to breed up bunches of Texas Horned Lizards, the charismatic and grumpy-faced little beasts that resemble nothing so much as spiky, disapproving frogs.

The species was once common throughout the state, before the marching cracks of development, invasive plants and fire-ants swallowed them up, pushing them out of the rich prairies of east and central Texas and forcing them west. The San Antonio Zoo is working with landowners to start reintroducing them on private ranches, in hopes of beginning to repair the fortunes of a much beloved species.

And in the DC Soviet, Saul is still churning out daily newsletters at The Hill — he has time, these days, for little else — that grapple, fundamentally, with the same big project that the San Antonio Zoo grapples with, which is the project of tikkun olam: the task of rebuilding what, over the course of our parents and grandparents lifetimes, has come so close to being decisively shattered.

On that note, we've got two entries for you today, and both of them are special. We've been wanting to use Heat Death as an opportunity to publish people we think are interesting, and have interesting things to say. So it is with great pleasure that we offer you the inaugural Heat Death guest essay by Annika Nilsson , anthropologist and crypto-epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis. Annika has some thoughts about trauma, and the ways that a seemingly concrete concept of physical brokenness has—without anybody quite noticing or intending it—metastasized into something omnipresent and inescapable.

And Saul , meanwhile, offers the first notes in answer to a question that has puzzled us: what would a fantasy world built of Jewish mythology look like? It would be a cosmology that embraces the fundamental fracturelines of existence, that draws from the Kabbalistic and the folkloric. And to understand it, you have to understand the place that God left empty, and what was built there, in microcosm of the creation of all things.

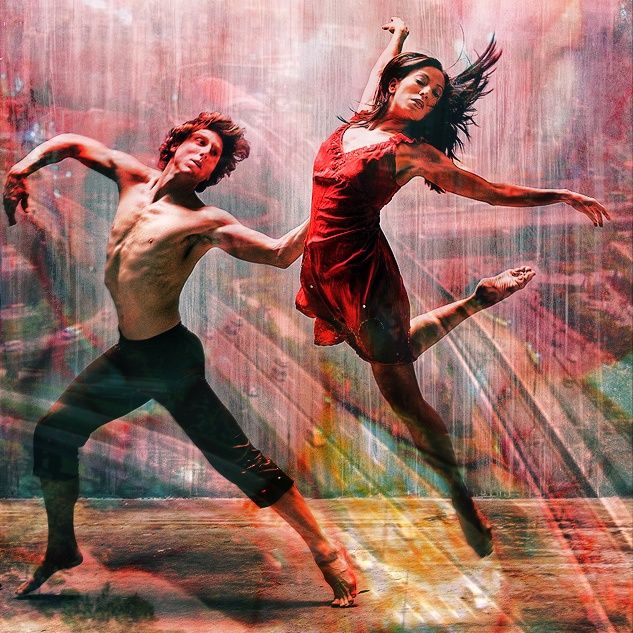

We're dancing around the question of what is broken, what is repairable, and what is left when misdiagnosing the one confuses the other.

As always, it's Heat Death. Stay with us.

Trauma Creep, or Why We All Feel Like Garbage

Annika here."Trauma" is something everyone has now. It slips seamlessly into conversation about our pasts, a grave and clinical moniker for baggage large and small. It's at home in the long lists of micro-identifiers that populate social media biographies. It neatly follows the possessive pronoun as one more thing taking up space in our lives - my keys, my phone, my trauma. It's everywhere. It's inescapable.

But where did it come from? How did trauma become the primary lens through which we make sense of the bad things that happen to us?

150 years ago, the word "trauma" - greek for wound - was used exclusively for bodily damage: broken bones, concussions and contusions, the visceral wounds of a life of physical labor. It wasn't until the turn of the 20th century that neurology and its newly emerging bastard child, psychiatry, adopted the term to refer to the lingering psychological and emotional effects of particularly awful experiences.

Early research on psychic trauma took soldiers returning from war as its paradigmatic case, although it also occasionally considered people who'd survived or witnessed terrible accidents. At the time, the nervous system itself was understood not only as the coordinator of motor function, the mechanical link between brain and body, but as a mediator between mind and physiology that imbued the body itself with emotional experience. Strong emotions, in this view, aren't psychological experiences isolated to the brain; they travel throughout the body by way of the nervous system, manifesting as aches, pains, tics, or appetite disturbances.

Thus, the French physician Jean-Martin Charcot—a pioneer in neurology and mentor of Freud—conceptualized psychiatric trauma as a physical injury to the nervous system, resulting from the overstimulation of overwhelming shock or terror. He spent a chunk of his career searching for visible evidence of nerve damage, or "lesions," in patients suffering from hysteria and post-combat symptoms.

Charcot's hypothesized lesions never materialized, but over the course of the 20th century, psychiatric theories of trauma developed into one that's passingly familiar to most of us: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. The basic theory of PTSD posits that encounters with extreme stress or danger, like the experience of combat or a terrible car accident, can cause a fight-flight-freeze response that overwhelms the nervous system, fixing specific details of the event in the subconscious. (You can think about this in a Freudian mode or a neuroanatomical one - either way, the point is that these responses aren't governed by conscious thought or intention.)

This is, perhaps, adaptive; preserving the memory of a life-threatening event (or one that seemed life-threatening at the time) is your basal brain's way of trying to keep you safe, should you ever find yourself in a similar situation. Suppose you get hit by a bus, and heal from your physical injuries, but dissolve into a panic attack the next time you hear the sound of a horn, or the screech of rubber and breaks, or smell diesel exhaust on a hot afternoon. Even though you might be sitting inside well away from the road, only experiencing traffic through an open window, in no immediate danger. But your subconscious remembers the time that you were. It tries to kick your ass into gear to face a serious threat by inducing the fight-flight-freeze response that feels, in the moment, like crushing panic.

This kind of automatic response was the first meaning of the term "trigger" - a sensory stimulus that causes the autonomic nervous system to respond as though you're in immediate danger, because it has associated that sensation with the past experience of injury.

But this understanding of PTSD is a snapshot of a bygone moment in the history of trauma. In the mid-20th century, "trauma" had a fairly specific meaning in the psychological sciences: a short-term experience of mortal terror, strong enough to stamp itself into the autonomic nervous system. In the late 20th century, research by feminist psychologists on the enduring effects of child and partner abuse argued that such intense and ongoing stress might have similar effects. Psychiatrist Judith Lewis Herman introduced to the clinical vocabulary the distinction between Type I and Type II trauma - the time-bound, near death experience, versus the enduring strain of chronic abuse and destabilization.

This was a crucial step in recognizing the gravity of the problem of family violence; drawing on the authority of the medical vocabulary around "trauma" was one way to push back against those who dismiss abuse as merely personal, a private problem, rather than an endemic feature a culture that teaches us to treat partners and children as property.

But broadening the definition of trauma also injected a mutability into the concept which has since led to a conceptual meltdown. "Trauma" is no longer only a brush with death, whether by bombshell or bus. Nor is it necessarily the hideous cumulative damage of decades of abuse. Now it stands for the full gamut of negative experiences, from a breakup to a violent assault, from catastrophic injury to the accumulation of microaggressions over a lifetime, from the experience of living in poverty to being betrayed by a friend.

Likewise, "trigger" has taken on such semantic lability that it can describe anything even remotely upsetting. (Inevitably, the latter has also been appropriated as a rhetorical bludgeon against the "liberal snowflakes" of the reactionary imaginary. From certain keyboards, it might as well mean "making people mad on Twitter.")

It's tempting to respond to this by drawing a line between "real" trauma and the mundanely bad, but by now I'm pretty sure this is a pointless semantic argument. (And when has anyone ever succeeded in turning back the clock on semantic drift?) Instead, we could ask: what does it mean that "trauma" so dominates our conceptual vocabulary for thinking about the bad things in our lives? And what other ways of coping with the deluge of garbage around us are we foreclosing by relying on it so heavily?

Trauma is a psychiatric concept, and therefore a medical one; it enrolls the events it describes under the umbrella of medical understandings of health and injury. This blown-open version of trauma marks basically all (or any) negative experiences as exceptional and pathological: a wound in need of therapeutic repair before its subject can resume their former state of health. In the U.S., where we've wholesale embraced the idea of health as both an unimpeachable moral good and the personal imperative of the good citizen, if there's something wrong with you, it's your duty to fix it. We must all return to a state of wholeness, health, and optimized productivity, less we burden those around us or, god forbid, personally damage the GDP.

"Trauma" thus encourages a person's withdrawal from the world into a state of therapeutic suspension. It becomes an all-consuming project, your whole life bending around the therapeutic techniques of self-repair - or at least, indefinitely suspended engagement with potential triggers. While we work on ourselves, we avoid people and places and media, classes and conversations and activities that poke at the bruises of our pasts - and we do this mostly alone.

In some ways, trauma represents an important departure from the late 20th century love affair with biopsychiatry - a neurotransmitter for every feeling, and a pill for every problem. Trauma, at least, acknowledges that our experiences matter, not just static brain chemistry. But if basically any negative experience can damage our primordial psychic wholeness, render us injured and catapult us into the lonely maze of Recovery, it's hard to imagine how we might ever find our ways out.

It's a catch-22. Leaning on the culturally sanctioned authority of medicine to legitimize an experience - to grant it credence and seriousness and public recognition - also enfolds it in a logic of pathology that's deeply isolating. In exchange for this medical stamp of approval, we've traded away the ability to talk about collective conditions: the manufactured scarcity, precarity, and omnipresent violence that make us feel so terribly ground down, that make it so difficult to meet our own basic needs, let alone to tend to anyone else's - to support our friends suffering silently behind closed doors.

Everyone I know has been hit by a bus. So we walk ever more gingerly, stop talking about buses, never mention the traffic. We stop going out altogether, stay home and do DBT workbooks and mindfulness videos and envision a future where we'll stop jumping at the sound of horns.

No one knows how to get the buses to stop driving on the sidewalk.

Annika Nilsson is an anthropologist and doctoral student at Washington University, St. Louis. You can follow her on Twitter @annikataraa.

Seven Theses On Gehenna

Saul here. A few months ago, Asher and I came across a tantalizing 2010 article from The Jewish Review of Books, called "Why There is No Jewish Narnia," which attempted to grapple with a mystery: why, the author asked, was all high fantasy — starting with JRR Tolkien and CS Lewis and on to JK Rowling — so very, very Christian?

Sure, he acknowledged, there's plenty of Jewish science fiction, not to mention superhero literature: in some ways, you can trace those traditions back past the silicon Kabbalists like Asimov to the speculative prophecies of Karl Marx. But in terms of the idea offered by Narnia — the parallel world — he argues that there is really nothing, and sets out to answer why.

His answers are tantalizing, if ultimately frustrating and unpersuasive. He argues that the magic that fantasy relies on is treated in Judaism as idolatrous; that there simply isn't the space in the Jewish cosmology for the kind of independent entities — djinn, demons — that populate fantastic realms. Then there is the Holocaust — a Jewish Harry Potter, he argues, would have to answer why the wizards didn't stop the the genocide. (To paraphrase Richard Rubenstein, how can there be magic after Auschwitz?)

I read this over the spring, and it caused a commotion in me — in part, because it seemed so wilfully obtuse. I mean, take his Holocaust argument: it leaves out, for one thing, the far more horrific possibility (which fantasy/science fiction writer Michael Swanwick explores in his "Mongolian Wizard" series as the proudly Jewish Harry Turtledove does in his Darkness series) of Nazi magicians turning to human sacrifice as a form of blood magic.

More importantly, it dismisses the great and tangled corpus of Jewish mythology, a canon defined by a monotheistic editorial gloss atop a great diverse jungle of the pagan — in which Babyonian night spirits like Lilith still stalked the snowy towns of the early modern shtetl, seducing the righteous to use their semen to breed her demonic children.

(Because, one imagines, among demons, as among humans, it is valuable for a child to be able to call on two cultures — like some other-worldly Quanah Parker.)

It annoyed me so much, well, that I had to start writing. Here is the beginning of an attempt to sketch out the world that a Jewish Narnia might take place in.

The Talmud teaches that when the Holy One, Blessed Be He, created the heavens and the Earth, he left one quarter unfinished. One quarter, to be occupied by any angel or demon, god or demigod, who thought it could do better.

When the rebel angels rose and fell with Lucifer, Venus, Star of the Morning, they settled here as refugees, weaving tents of leftover dream stuff. When the pantheons on Earth — those councilors and playmates of the Old One's early days, when He and the World Tree were young — were purged, they too settled here, to live lives of barbaric grandeur or quiet obscurity.

In the Talmud, this world is called Gehenna.

The Rabbi of the Warsaw Ghetto, as typhus and starvation, cold and despair, thinned his congregation, steeled himself against despair. In his drafty rooms he composed a radical new gloss on the theory of the Kelipot, the breaking of vessels that in the Kabbalistic account creates the world — that, as we might say, plants the Tree.

The Kelipot, he argues, in an echo of the multiple cataclysms of Maya or Hindu time, or the modern geologic account, was the breaking not of some primordial stuff but of living, populated worlds; the seeds of our Creation were laid in the shattered ruin of worlds as fragile and wondrous as our own.

As his people vanished, Rabbi Shapira suggested that all that kept reality whole after the destruction of Jerusalem was the principled deaths of the Ten Martyrs — it remains one of the Holy One's favorite things to see. (Though He swears He's still sworn off human sacrifice.) Should things continue as they were, Shapira speculated, it would not be unreasonable to think a new shattering might be upon us.

In this, of course, the rabbi was correct.

Gehenna is identified with a realm of fire and torment similar to the Christian Hell. This is largely inaccurate, although the reformatories and torture chambers of the Most High are largely located here, where it is deniable. (We may imagine black sites, perhaps, run by demonic contractors.) Gehenna is but a small part of the Outer Lands, the far countries beyond the thrice nine kingdoms, which go on for what seems like ever. Go far enough, and you get the feeling that you are running into some echoed version of yourself.

Like everywhere else in the Outer Lands, or the Worlds of Emanation, true creation is impossible; true existence and agency apart from God difficult, as God's very presence tends to corrode anything he touches. (He is not always safe to be around. But He's getting better.)

What there is instead is reflection: of what has been, grown, been made, evolved, on Earth. The Old One set in motion great forces, assigned them to subordinate creatures who once we called Gods, before He became jealous of this term; then He cut them loose. And what the beings of this realm — our realm — create, Heaven may remix, make use of. It's a low-power burn; a manageable tool. After all - why cook with the plasma heat of a star when you can use a Coleman stove?

There is also, of course, that raw creative power of God's to intervene in the world; or to remake himself or the Heavenly host. But He doesn't like to use it that much anymore. He still doesn't trust himself.

But like I said. He's getting better.

The capital of Gehenna, if so anarchic a place can be said to have one, is a city where reed canal boats — an affectation, brought from Earth at great expense — slip down cold black rivers reflecting the flickering of kerosene lamps beneath a sky of endless night. This is the city of New Babylon, and if you turn from the Great Market — stalls of iPads and fine papyrus, lowing cattle and clockwork machines, smoked paprika and the dreams of children — and lose yourself in the curving warren of streets, your thoughts on a place halfway between going and arriving, your eyes pushing in an upward spiral gently into your forehead — then perhaps eventually you will find yourself, by a route you can't remember, at a tall brick house with a pointed turret roof rising to a tip sharp as an arrow.

This is the office of Lucifer and Satan, who have worked together for so long that few remember them as separate people. Lucifer, the Son of the Morning — although, of course, she goes by Venus now, ever since she quit the job as the Old One's right hand and retired to Gehenna to take a job in the private sector.

Satan, meanwhile, still takes gigs sometimes with the Heavenly Court. He has the kind of relationship with the Boss that only the most favored get: the cherished right to say "fuck you" to a Being that can destroy universes with a thought. It's not just that he's the best prosecutor on the Tree — get rid of him and what, you're going to bring in Metatron? Get real — but that he has that thing the Old One most desires: the capacity, every once in a while, to make Him laugh, and forget the burden and loneliness of eternity.

The Lord keeps Satan around because he can score a point — and though no one ever says it outright, Satan has a pretty good sense that that's the only reason the vindictive fuck (blessed be He) lets Lucifer live in peace.

The air is still in Gehenna; the shadows long, luxurious as velvet. Two people sit together in a tall brick house, by the flickering light of a kerosene lamp. One is a woman with long white hair, her lean body wrapped around a cup of coffee, a cigarette dangling from her silver holder. The deep lines on her face are stark in the flickering flame. Her companion is young, and her dark eyes are fixed like searchlights on the older woman's face.

"Now look," the older woman says. "If this story sounds derivative to you, consider carefully the phrase 'Primordial Action' and think about whether you may have got cause and effect backwards."

"What?"

"Don't interrupt. The first thing you have to understand is that in the Beginning, there was no Him. I mean, not really. He had brought it all into being, if you want to try to say it that way. But the whole story makes a mockery of cause and effect. He was the universe and the universe was Him, in an ocean of boiling potential, too hot and potent to even emit light. Did He know himself? Was He born? Did He create or was He created? I doubt even the Old One knows, or remembers, if He ever did. I don't know if the answer has any meaning."

Venus—called Lucifer, once, the Star Of the Morning—taps the cigarette against the kerosene lantern and makes the shadows jump.

"And He is very old. But look: those questions have no meaning because in the heart of the fire there is no space; there is no form. As They — they were still They — began to understand that They were there, They began to pull Themself back; to create a space where They were not. A space where something Else could be."

"A space?"

"The creation before any creation is possible. Take these same walls and squash them flat. We have all the same materials, but do we still have a house? They made a hole in Themselves, and into that space they blew and heard the awesome music possible when Something drifts across Nothing. They saw, for the first time, in that drifting mist of Non-being, shapes."

Venus sees the bafflement on the young woman's face and shakes her head.

"Not if you try to digest it all in parts, child, no. You must ride it quickly like a bicycle. Hush and listen.

So: They opened the space where something else could be, and into that hole They danced with Themselves, and as they danced, two began to spin from One. He began to spin away from She, as mud and water flee each other at the end of the river's ball, as the floodwaters lose their energy and the land and water must separate again. Eh? Like that.

In that space they found each other, again and again, and each time there was more form between them; they were shaped by their dance into corresponding forms. She pulled back from Him and guided Him on; He stood solid as She spun around. In the rushing water of the deep — for the space they had made was, miraculously, without end, infinite in both space and possibility — they closed and separated in the ecstatic joy of separation and union, He and She and They again."

"...Look." The young woman shakes her head again. "If there is one thing that was made clear to me growing up, and that has been made ever more so here — it's that there's only one God."

Venus laughs, a silvery sound. In its glass cage, the candle flares.

"It's more complicated than that; She and He were one, or had been one, or were constantly becoming one. Do you understand? Their very separate existence was unstable. They could not keep apart. Was He more powerful, like a human male? Sometimes He was enormous and She was tiny; sometimes He was a flea and She hovered above Him as a mountain. But for a world without end — time has no real meaning, in that space before Creation — they flickered and followed and separated and merged.

As they did, by the way, with other parts. There were and remain many Selves, many Names, you understand. But most did not separate off. Most did not assume the force to maintain Their own identity for long."

"But she did."

"Yes. Well. Until, that is, He struck Her down. And in his grief, planted the Earth on Her shattered body and swore He was going to change."

"… He murdered her?"

"Not ... quite. He talks that way sometimes, but no. They had begun to play with form and matter. They were building things of fixed shape. She took on form to please Him — it was new to them, then. It was new in general. She got caught up, somehow, in being, and when he tried to pull her from it, she resisted, by instinct.

It was a new feeling — the pull away, not to coquette but to say, "No!" He reacted and pulled, and so did She, and in His shock and surprise and rejection He poured his rebuke into Her as He might have if still They danced formless on the Deep. And if They had, She would have absorbed it and danced around it and returned it to Him, and They would have returned to Their play."

The young woman stares at the kerosene lamp. "But she was form."

"Yes. She had become, in that time — for time to Them meant nothing — a World, as intricate and beautiful as your own. Beautiful, material — and fragile. And so He broke not against Her infinite majesty but against thin matter, and She was caught inside when He broke it apart and scattered it throughout the hollow where once They had danced, where they scattered on the surface of the formless deep.

And in His grief, among the shock and raw power, He would have destroyed the universe again, returned all to formless void — except that He saw, in the floating mass of Her ruined body, that something remained. A flicker of life and love, locked deep in the fabric of matter.

And He blew upon the surface of the waters, and He began to form Her shattered body into mud, and from it He planted the Tree. He has been searching for Her ever since."

But that was a long time ago. Before Venus, before Satan, before even Gehenna of the empty quarter, where the gods retire and the demons have their shanty town. But still, sometimes the Shekhinah—the divine presence, the light of Her— whispers around Him like a curtain and drapes His shoulders; settles over him like a warm summer night back when the Tree was young.

There is a crack in everything; that's how the light gets in. This has been Heat Death. Drive carefully.

Member discussion