Welcome to the Lizard Factory

Saul here. It’s not a day any Texan forgets. When I was 19, I took off with my then-girlfriend Nicole on a road trip from Austin up to Glacier National Park in Montana.

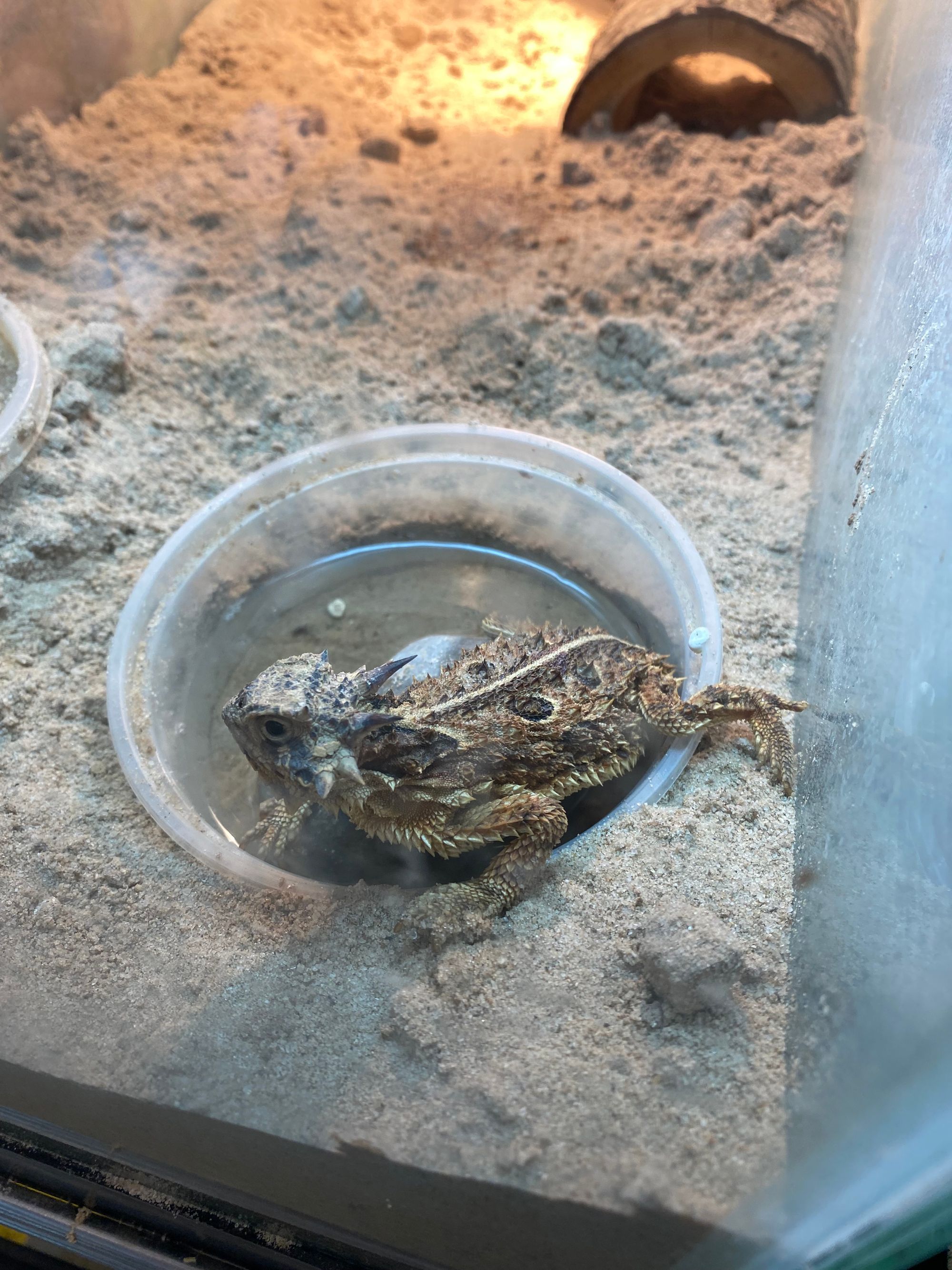

Waking up the first morning near Palo Duro canyon, our pallet laid out under the sky, we pulled back the sleeping bag to discover, crouched in the shelter beneath to discover a squat, beetle-browed little creature, its face furrowed in a masque of permanent and resigned worry. As though it had always known things would reach this point but never thought it would happen so … soon.

Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that always thought it would happen so soon.

Mid-August finds the Brothers Elbein hard at work on bringing Heat Death to its next phase. That’s going to mean a major membership push, a few long-form projects, and a prospective anthology of the weird, in which we aim to crowdfund the money to commission writers for a collection of 10 fiction and nonfiction pieces that would have homes nowhere else.

But for now, we have something much lighter for you: a fascinating conversation with a man trying to return these worried-looking little lizards to the vacant lots and backyards of Texas. Even if you don’t much care about Texas or horned lizards — and if that’s you, how on earth did you find us? — his agenda is fascinating: to use the creatures as “a Trojan Horse”: the thin tip of a wedge that can be hammered into the Texas discourse around lands, a way to shift the way Texans — and particularly the nouveau riche and patrician second-home owners who he sees as most persuadable on conservation — think about their responsibilities to the land, and the unexpected values it can provide.

When Asher visited the D.C. Soviet in early August, he laid out a working theory of effective conservation propaganda: if you want people to care about, for example, Mexican free-tailed bats, it does no good to give them long lists of the ecosystem services provided by bats, or the savings for farmers, or anything like that. (You need those analyses, mind — but more to convince people that you’re serious than because anyone actually cares.) But if you want them to care, what works is much simpler: “You have to hold a bat. And then it’s like, look at his wings! Look at his little ears!”

The horned lizard sticks in the Texas consciousness because it fits our image of ourselves — pugnacious, tough, spiky, laconic — and because it connects us to a memory of what the landscape once was. That memory contains within it a vision for the future, too, of startling propulsive power — that a landscape hospitable to a new generation of horny toads will be a landscape far more hospitable, as well, to humans and other animals.

But connecting to that, physically or metaphorically, means picking that lizard up. I still remember the weight of that lizard in my hand almost 15 years ago; solid and surprisingly heavy, cool in the desert dawn, waiting patiently to be put back down. A vision of the world that was, and of what it could be.

And so, without further ado: the horny toad interview. Stay with us.

Asher here. I, like many Texans, have long been utterly enchanted by the Texas Horned Lizard, popularly known as the “horny toad.” They’re pretty delightful creatures: flat, stubby tailed, with pinched, disapproving little faces and a crown of sharp horns on the back of their skulls. They’re also severely threatened in large parts of the state of Texas, and have basically been eradicated from the state’s eastern third. In addition, the species is notoriously difficult to keep in captivity, and is pretty damn finicky about breeding, too.

None of that has stopped the team led by Andy Gluesenkamp, the director of conservation in San Antonio Zoo’s Center for Conservation Research. (Picture a friendly, rather soft-spoken man who looks not entirely unlike Alex Jones.) Prior to joining the zoo, Gluesenkamp served as Texas Parks and Wildlife’s state herpetologist, where one of the most frequent questions he got was “what happened to the horny toads? What are you doing to help them?” Now, Gluesenkamp and his colleagues are working on reintroducing the lizards into the wild.

I recently dropped by the zoo’s horned lizard breeding program for an upcoming Texas Highways story. In this interview—edited and condensed for length—Gluesenkamp and I talked about Texas’ favorite lizard, navigating land-use practices, and how to get a breeding program started.

Tell me about horned lizards.

If you talk to native Texans my age or older, and they lived somewhere between San Antonio, Dallas, or Houston, they likely have fond memories of abundant horned lizards. There are actually three species in Texas, but the one everyone is concerned about is the Texas horned lizard—which, despite its name, actually has a huge range that includes several states and northern Mexico.

Historically, its range in Texas was about two-thirds of the state. The issue is that beginning in the 1950s, they started to decline or disappear from a lot of places where they were formerly abundant. The Eastern third of the state is where we’ve seen the most dramatic declines in horned lizard populations, and that’s also where the majority of Texans live. I’ve had individuals come and do a behind-the-scenes tour of our horned lizard population here in the lab, and tell me, “We used to find them right here in San Antonio, they were in every dirt alley, every backlot. What happened to them?”

So what did happen to them?

When was the last time you saw a dirt lot or a back alley in Central San Antonio? It’s not just habitat loss, though. These animals aren’t all that good at dispersing. A horned lizard, for it to get from one place to another, has got to walk there on very short legs. Bring in other factors like cats and roads, and urbanization is a very obvious threat.

Others are less obvious. For example, non-native invasive grasses like Old World bluestem was brought into Texas rangeland as forage for livestock. Well, turns out, it’s not the best thing for livestock, and it’s a terrible thing for horned lizards and other species. For an animal that spends its life an inch off the ground, those dense, dense patch of non-native grass are basically an impenetrable bamboo thicket. In addition, not only do those plants support a lower diversity of arthropods, but also a lower biomass. So you have fewer individual predators like horned lizards overall.

We may look out at a pasture and say, “That looks great!” But most of us aren’t critically assessing the community structure, or putting ourselves in the horned lizard shoes and thinking about: Well, how would I traverse it? Is there shelter within a quick scramble from where I’m at? Is there food within a quick scramble of where I’m at?

People tend to blame the decline on fire ants, don’t they? How much of a role do they play?

Oh, red imported fire arts get all the blame. They suck! We hate them! They’re terrible for a whole lot of reasons! They compete with the harvester ants that the lizards eat. They attack harvester ants. They attack lizards. Sometimes — and this is really brutal — when a collection of eggs is hatching, the ants will actually eat them out of the eggs. And if you look at individual horned lizards from areas that have a high fire-ant density, you might see even adults missing toes. This is true of a lot of lizards species.

So they deserve some of the blame, sure. But they’re not the single factor responsible for the decline or disappearance of horned lizards. We bear a lot of responsibility.

Tell me about the breeding program you have here.

I call it the lizard factory, but it’s kind of tongue in cheek. The strategy is to produce large numbers of lizards for release. You’re trying to replicate or exceed the reproduction that you would see in that healthy established population. So the strategy for every [reintroduction] site is 100 lizards per year, for three years. Following that it would be 25 lizards a year, every other year, maybe indefinitely. Or you can release 300 lizards all at once, and then do 25 a year.

Obviously, because we’re still scaling up our lizard factory, we’re planning on doing 100 a year right now. We simply have not been able to produce 300 hatchlings yet: right now we have a little less than 80 after the last release.

What’s the benefit of releasing so many?

The idea there is that you’re getting ahead of just the natural mortality rate for young lizards. Hatchling horned lizards, they’re very delicious. Nature’s popcorn. They’re harmless, they’re small, a wolf spider could eat one. And so it’s real tough for them to get from hatching to adulthood.

Part of our strategy here is that we grow them up as big, fast, and healthy as we can before releasing them, to get them out of that danger period where they’re everybody’s prey. When they first hatch, they’re too small to even eat harvester ants. We want to get them to the point where they can take advantage of a full menu of potential prey items on the landscape. That gives them a good head start.

How many breeders do you have, and where are they from?

Our target number of breeders for this lab is 50. We’d really like to be at a point where we have 150 or 200 breeders. So we strive to get lizards from different populations—we sort of have our own rule that we don’t collect more than five animals from any one site. That’s to minimize any potential impact to wild populations, but also to maximize the genetic diversity of the animals that are in the lizard factory. And so, as a result, no two horned lizards here look the same, because they tend to be very closely color-matched with their background with the soil where they came from.

Of course, all of our lizards are collected under permit. I have some permittees who have access to private ranches, and some of them come from places like that. But that permit has a special stipulation that allows us to collect from the road surface itself. Most of our animals were plucked up off of the blacktop, where the next car might have been the one that did them in. If we can, why not? Lizards that live on or near roads have a greater chance of mortality.

...maybe we’re selecting for stupid lizards. [laughs.]

So what goes into actually breeding and raising them? They’re famously finicky.

Well, they’re solar powered and they run on harvester ants. They need a lot of harvester ants. We’re talking about 50 to 100 ants per lizard per day. Also, they’re not like a dog that’s gonna go and just drink out of the water bowl. Sometimes they soak, but they need regular misting.

We’re working with the South Texas form, for obvious reasons, and other zoos are working with the North Texas form. For a lizard that lives in North Texas or the Panhandle or something, hey, a long, cold, dark winter, that’s fine. A lizard that is used to being out and about all 12 months of the year, that’s more than they can handle. So we had to develop our own protocol for how we overwinter the lizards, so that we don’t lose lizards during hibernation.

Who would have known, right? But those sorts of differences you only start to learn once you’re doing it, and once you’re doing it at a certain scale. If you had one or two lizards that you’re working with, you might never be able to figure out what that pattern is.

Have you done any releases any yet?

Our first release was last year in October. Hopefully, knock on wood, we’ll be doing our second release at that site, late summer, early fall of this year.

You know, it’s not so simple, breeding and rearing these guys in captivity. And there isn’t an owner’s manual for it. So we have benefited quite a bit from lessons learned from other institutions that worked with them, both what to do and what not to do. We were the last to the table of the three Texas zoos who are working with horned lizards, but we got off to a really good start because we had the benefit of lessons learned by these other efforts. Bringing in all of this academic research and looking at other fields of study, like the satellite imagery, to craft what we hope is going to be a successful, long-term reintroduction effort.

This program was one of the first you launched when you came to the San Antonio Zoo. Why horned lizards?

Being the state advocate for reptiles and amphibians, that was a really lonely position. You have a lot of adversarial interactions with different stakeholders that don’t necessarily see reptile and amphibian conservation as a priority. So I really wanted to find something that was a win-win-win, right? That would be good for a species of concern, would be good for our program, something that people could get behind.

Everybody likes horned lizards. And that makes it a lot easier to get people on board with what we’re doing. We’re striving to fill a void that so many Texans feel with the absence of horned lizards. That’s one of the primary motivations. Another is restoring this really iconic species to our native landscape, which involves managing coordinated biodiversity.

Is the idea to use them as a keystone species? A species whose conservation shelters other animals as well?

Sort of, yeah. Managing landscapes to support more lizards requires managing the plant communities, those non-native invasive ants, and so forth and so on. It’s a bit of — I’ll be honest — it’s a little bit of a Trojan horse for me. A goal of this project is to encourage voluntary action on the part of private landowners to enhance and support native biodiversity, which benefits the both the landscape and the landowners.

Say more about that.

There’s been a shift in the profile of your typical Texas landowners—the ones that own hundreds or thousands of acres—in recent decades. It used to be they were these old German farmer or ranching families that were driven to use that land as much as possible, to wring every nickel they could out of every acre. And that leads to… certain suites of land management practices.

But then the last few decades, we’ve seen the rise of the non-traditional land owner. Individuals who are not born into ranching or farming, who bought the property not for agriculture but because they want the viewscape. They want a wild place for their family or for their grandchildren to visit, or for hunting opportunities. Which, once again, ties into that mode of biodiversity, especially if you’re talking about game species like quail—which have virtually the same habitat requirements as horned lizards.

I’m not faulting traditional landowners, by the way. I understand if somebody has got, you know, a production ranch or farm. They say, “Well, wait, how many acres of cotton am I gonna give up for horned lizards? I’d love to, but, you know, this is how I feed my family.” I’m just saying that these non-traditional landowners tend to see a greater value in native biodiversity, native landscapes, plant communities.

Do you guys ever end up working with folks who run exotics on their ranches?

Definitely. But I mean, cattle are a non-native as well. If they’re managed properly, you’re partially emulating the effects of herds of bison. Those are adding benefits not just to horned lizards, but to that native landscape, by performing all those ecological functions that they do.

And on the other hand, I’ve been on ranges out and outside of San Angelo that were “goated to death” [subjected to continual close grazing by goats and sheep] and just looked like a moonscape. And there were horned lizards. Sometimes livestock overgrazing actually ends up opening the range up for this species.

Like a new ecological succession process?

Yeah, or they help keep the woody vegetation from encroaching. Or they spread around the seeds and native grasses and forbs, depending on what they’re foraging on. There’s no absolute in terms of livestock, or exotics. It’s not as simple as “don’t graze animals.”

What’s the process of working with landowners been like? How suspicious are they of reintroduction efforts?

You know, I spent the last 20 years or so working on groundwater salamanders, the little cave salamanders, cave spiders, that sort of thing. It’s a tough road to hoe to get your average Texan excited about some little blind spider — get them excited in a good way, I mean. It requires very little cajoling to get them behind horned lizard conservation. In fact, I absolutely guarantee if you punctuate your story properly, we will receive a lot of calls and comments from the public about how they can get involved. There’s so much affection for horned lizards— especially among sections of a certain age where they actually have firsthand experience with them—that I don’t really have to pitch why the project is important.

We actually kept the project on the downlow for several months, while we were getting our ducks lined up. I was concerned that, because I knew that there’s so much enthusiasm for horned lizards, that we would just be hit with a firehose of landowners. We don’t have a huge capacity, and it’s just not possible for us to meet all of that demand. So I didn’t want to be inundated and then not be able to satisfy these people.

But it’s my Trojan horse for convincing people that we don’t have to fear reintroduction or restoration efforts. There’s no need to be adversarial when someone talks about bringing back an imperiled lizard. Getting people to see that with this really charismatic species, I’m hopeful that that’s going to lead to sort of long-term sea change, alteration of people’s just fundamental position with respect to reptile conservation.

So how do you go about selecting a site?

We’ve developed a list of criteria for candidate sites. It needs to be within the historic range of the species. It’s even better if we know that they were there at some point. It needs to be suitable acreage, and preferably adjacent to other patches of suitable habitat, or patches that can be improved to serve as corridors. The idea here isn’t little decorative populations that are in the middle of some individual’s ranch, but to reintroduce this species to large swathes of landscape.

A landowner comes to you with his boundary lines and you can easily assess the plant communities, which is the proxy for horned lizard habitat, from satellite imagery. Sometimes you can see harvester ant-mounds, that way. You can then offer a prescription for different management practices. For example, if it’s all woody encroachment, or non-native invasive grasses that need a few good rounds of prescribed fire and reseeding with natives, you can make a pretty substantial improvement in a few years. We’re able to provide some timeline for landowners—maybe a few years—which is really important for keeping people engaged. And those management practices benefit native biodiversity, regardless of when or if they get horned lizards on their property.

But we want them to commit to basically managing in perpetuity, right? If they’ve got half a mind to strip-mall the site in five years, then we don’t want to establish the population and then lose it.

What about checking for stuff like fire ants?

Well, it’s pretty much impossible to see fire-ant mounds from space. So one of the steps that we do is boots-on-the-ground assessment, literally kicking some dirt. The presence of fire ants is not a deal breaker. It sort of depends on the density. If there’s a real high density, you’re almost always gonna see a reduced abundance of harvester ants. The ranch where we conducted our first release back in October, they have both.

The thing is, we can’t use typical ant bait and poison to treat fire ants, because they’re general poisons, and they’ll kill every species of ant. Fire ants are like mushrooms, right? They just pop right up after the rain. And in part because they have hundreds of queens per mound. Harvester ants colonies take about five years to reach a mature size, where you see that big gravel clearing around the mound. That single queen, she can live for 10 or 15 years or more.

So I really try to impress upon people that harvester ants are like oak trees. They’re really important to their landscape, they’re very slow growing and long lived, and once you wipe them out, they don’t just come back. So you wouldn’t cut down, poison, run over a nice live oak on your ranch, right?

It’s interesting how much runway is required to get one of these programs up and running.

Yeah. One of the other goals of this effort, other than getting the horned lizards back on the landscape, encouraging voluntary biodiversity management, is to develop replicable protocols for doing what we’re doing. Basically, I want to have a lizard factory manual that I could share with other zoos, with precocious landowners, with other conservation and management entities.

Because there’s no way that we’ll ever be able to meet even 1 percent of the demand that’s out there. But we can work on best practices and documenting that so that other people can do that. Other than our finding lizards or reproducing in the wild after we’ve released them, that’s the other major milestone that for me. Once we complete that, we’ve accomplished everything that we wanted out of this.

Anything else you think people ought to know about horned lizards?

They’re a protected species. It’s illegal to catch ‘em, keep ‘em, sell ‘em, trade ’em, breed ‘em, all of that. We have special permits from the state that allow us to do this project. Also, they just do not survive well in captivity. And so anybody reading your article should be cautioned: Don’t do it. The lizard will die. So if you care about horned lizards, work on indirectly helping horned lizards by supporting efforts like ours, or making space for horned lizards in your world.

Thanks for taking the time, Andy.

My pleasure.

That's Heat Death. We're still looking for your letters and questions, so send them in to aelbein@gmail.com, and be sure to subscribe if you enjoy what we're doing. Till next time.

Member discussion