Do Birds Matter? (Monsters are Creatures of Borders)

Look.

Over there, in distant lands, in places that slouch between between the real and the imagined, between here and there: crossroads and shorelines; derelict houses, lost cities, and back alleys. Out there, something is stirring. Out in the swamp, black water bubbles, and huge forms shift among the shivering trees. Out on the high crags, weird wings unfurl. Out among the graves, dirt buckles and writhes, disturbed by a knocking underground. Out in the vast depths of the starlit ocean, undreamt terrors descend our way.

There's a darkness outside of town. A shape at the corner of your eye. You can feel it, can't you? Boundary lines are being crossed; the unknown is bleeding in. These are monstra: portents, warnings, deviations from natural law.

But nature is vast, and laws are a thin slick of oil spread on a heaving sea. What is a monster? It is an invitation to cross a threshold. Come and see.

Welcome to Heat Death, the newsletter that never drinks… wine. Thank you guys again for subscribing!

Late May finds the Brothers Elbein on the cusp of summer, in that dreamy intertidal zone between basically pleasant weather and the coming, crushing heat. In Washington DC's Farragut Park, where Saul is writing this, the sparrows gathering dry straw for their spring nests visibly prefer the shade. Reflected heat rises off the green lawn like a taunt: enjoy the cool breeze if you like. I'm coming soon enough.

Our father, the venerable Brad Elbein Esq. often quoted a line from Jacques Derrida's Of Grammatology, that the future, as the is "necessarily monstrous," because, as Derrida told an interviewer, it is

that which can only be surprising, that for which we are not prepared, you see, is heralded by species of monsters. A future that would not be monstrous would not be a future; it would already be a predictable, calculable, and programmable tomorrow.

The horror comes as a kind of revelation: the new rises up above, all claws and teeth. Only with time, Derrida writes, can we "domesticate it, that is, to make it part of the household and have it assume the habits, to make us assume new habits. This is the movement of culture."

On a walk this morning, Saul spotted something ominous: a brittle, brown, split-open shell, six empty legs where something had emerged. They were all underfoot, the first waves of a long-awaited Cicada swarm dubbed— in 50's horror movie fashion— "Brood X." When the cicada larvae emerge aboveground for the first time in almost a human generation, they leave behind shells reminiscent of the castoff face huggers from Alien. But many of them arise only to be consumed.

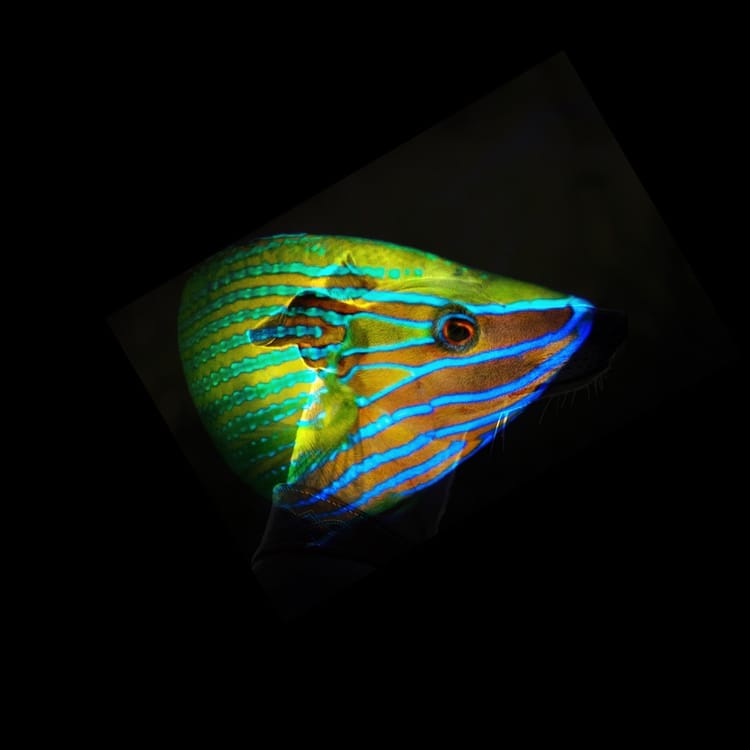

A little brown sparrow flew by, something struggling in its beak—a cicada. He imagined it: emerging from the safety of seventeen years of darkness, ready for your first and only party, to be immediately confronted by flocks of nimble, ravenous dinosaurs some 30 times your size. The bird, a Eurasian sparrow, is also the sort of bird that his partner Anush had pulled, shaking in terror, from the mouth of their cat Leo a few weeks ago. Cicada, sparrow, cat. Who, then, is the Monster? Is it simply your species' particular scary predator, or must it have an element of the uncanny or unknown? (When does "Man, some heat we've been having" turn from inconvenient, to dangerous, to monstrous?) If we say the real monsters are humans, does that reflect our unpredictable and unstoppable tendency to change the parameters of the entire board?

Asher's spent May wrestling with these questions, writing little daily pieces on the theory and philosophy of the monstrous. We'll be doling those out like the good liquor over the next few weeks, in little thematic packs to amaze and astound you.

We've got three pieces for you this week below the jump. First, an introduction to the study of monsters; second, a confrontation with one of the key philosophical issues of our time; third, a dialogue on planning for recession and failure.

It's Heat Death. Stay with us.

THE MONSTER IS THAT WHICH BREAKS THE RULES

Three introductory rules on the detection of monstrosity.

Rule 1: A Monster Lives Just Beyond the Veil

We have already established that monsters thrive best in liminal zones and boundary lines, the place where *over there* becomes *here.* A monster isn't a monster if you see it every day. For much of history, traditional peoples living on the landscape have seen lions and crocodiles as facts to be worked around: inconvenient, even dangerous, and imbued with spiritual meaning, but not deviations from any natural order. For us to encounter a monster, it must either have left its natural home—Grendel rising from the mire to execute world's bloodiest noise complaint, Dracula leaving his castle in search of newer, paler necks—or we must, ourselves, go somewhere we are not meant to be, whether that's a Black Lagoon or the depths of space. Someone, in other words, has to go somewhere. Some has to step across—to literally (and latinly) *transgress*.

Monsters, therefore, dwell beyond veils and depths. Where the forest or jungle swallow the light, scattering sightlines in layers of leaf and shadow. At sea, months from sight of land, or 20,000 fathoms down. In bleakest desert or the highest mountaintop, or in black caves plummeting to the roots of the world, where unseen things lurk. In the creaking silence of an abandoned building or castle, where the halls are a maze that draw you ever further, ever deeper, and history weighs on your every step. In Transylvania, the land beyond forests, and Skull Island, a jungle behind a wall behind a thousand miles of crashing, murderous sea. In back of beyond, and behind the thrice nine kingdoms. Far enough to be hidden. Close enough that someone…

...or something...

Can step through.

Rule 2: Weather is a Gateway Between the Worlds

Generally speaking, you will not find a monster on a perfectly pleasant, 75-degree day, with the sun beating down, a nice breeze, a few clouds in the sky. Monsters thrive best in occluded conditions: storms, mists, blizzards. (Monsters arriving with the intrusion of water—in the form of rain, sleet, snow, mist, fog—is a common theme. And why not? Water is a gateway to other worlds in both the literal and spiritual sense, a symbol of intrusion as much as it is life. The rain and snow come down from some other place. Who knows what they bring with them?) But daylight isn't necessarily an anathema to a monster. Consider the pure, killing heat of deserts, or in the full glare of the summer sun: the mirage-times, when the air itself shimmers like a veil, creaks like a table bowing under the weight, and you cannot be sure that what you see is real. That is the key point, perhaps. A pleasant spring day hides very little. A rainstorm or blizzard or a mirage hides a great deal.

Yet the relationship between monsters and this sort of weather is hazy: are they attracted by it? Do they, in some sense, create it? Does the natural world react to their coming, growing restive and unhappy, warped by the sheer weight and presence of the unknown? Are we simply more likely to see a monster when looking out into the rain, and wondering what—if anything—walks beyond the falling drops?

Rule 3: The Monster Story is a Door that Only Swings One Way

It has been remarked that there are only two types of stories: a person goes on a journey, or a stranger comes to town.

Generally, this is nonsense: there are no monomyths, only multiple reflections of common human experiences. But with monster stories, it's true. Monsters, as we have seen, are symbols of transgression and boundary-crossing.They require somebody to go somewhere. Sometimes, what they require is for a monster to appear in a story genre that does not typically have them: historical fiction, family drama, crime thriller, romantic comedy. Their appearance can be a shock, or they can be woven into the fabric of the story from the beginning. But the appearance of a monster transforms the story it's in. From Dusk Till Dawn is defined by the sudden appearance its vampires, after all, and it's hard to care that much about the marital infidelities in Peter Benchley's novel Jaws once the shark shows up.

Monsters are a narrative threshold that cannot be uncrossed. They are a state change. You thought you were in a world of frock coats and familial obligations, where the strictures of life may bind us but seldom surprise us—until the shape slouches across the moor. You thought the heist was dangerous, with its trip-wire-taut logistics all that stood between you and prison or a bullet—until you heard scratching at the door of the vault. You thought it was summer, and graduation was a year away, and the water looked so cool, so inviting...

Once a monster arrives in the story, the world has broken and remade itself, and the days of predictable seasons and pleasant harvests are gone, swallowed up and changed into something new and terrible. Once a monster arrives in a story, what follows is always a monster story. No matter what.

Hot Take

Do Birds Matter?

Being a series of unfair and largely specious critiques of Jonathan Franzen's 2018 National Geographic cover story (displayed below), which was recently discovered in grandparent-in-law's country house.

- That is not a question asked by a man fully confident that birds matter. (Think about it. The cicada or squirrel dumb enough to stop and ask why birds matter has already been eaten.)

- Franzen is bold to tackle this question, but he should have gone further, and asked: do birds matter?

- To which we can say, after years of study, that the answer is, of course: No, but it has proven impossible to convince them of this.

- He also sadly leaves behind another important question: are birds matter? To this question, he could have easily answered: yes, the Stanford's Hansen Physics Lab has discovered that birds represent a fifth state of matter, which explains their ability to shapeshift on cold days.

- Deep in the article, Mr. Franzen notes that the question of Why Birds Matter must be addressed, sadly, because people at dinner parties, unconvinced by his hobby of globetrotting around the tropical world looking at rare warblers, kept asking it of him. We leave it as an exercise for the reader to imagine the madness that would ensue if other common, but stupid, questions asked at American dinner parties had to be dignified with their own defensive cover articles.

- Seriously: why not just "Birds: Still Cool!"

- Franzen finds that for all the ecological importance and wondrous complexity of order Aves, they sadly don't pull their weight economically — and yet, he reminds us of what they do for our souls. He is right about the connection between birds and human souls, but he has the relationship backwards.

- As is well known, crows gather bits of human soul to divert their hatchlings, and many species of magpie decorate their nest with particularly diverting dreams they steal from human children. In old Anatolia, the vulture gods came to collect human souls, and humans liked to believe they brought them safely to the land of the dead.

- They didn't.

- In the DC Soviet, the presence of birds is announced with an occasional gentle thud as the cat loses control and bounces off a window.

- In this article, Mr. Franzen makes the genuinely rookie mistake of trying to wow us with the diversity and majesty of bird-dom — as though this will convince the imagined person going: "I dunno, man, I care more about people."

- The proper response to this person is: the thing about birds is that they are bastards. This is sometimes lost on those who are distracted by their beauty or engaging behavior or their appealing relationship to dinosaurs. Mockingbirds? Stylish, elegant bastards. Hummingbirds, consummate bastards. The peaceful cooing mourning doves at Saul's window; the gentle clucking hens that ran around Asher's Austin backyard? Bastards. Corvids — magpies, jays, crows? Too complex to always be bastards, but a definite bastard streak, displayed against those who are bastards to them, or to hawks, or to humans who have left tasty snacks unguarded or otherwise put on airs, or when they just don't have anything else on.

- This ultimately is why birds matter: they are watching you, everywhere, at all times.

- There is about Mr. Franzen's argument a whiff of desperation, as though he does not expect, perhaps, that the birds will believe his conversion is genuine. Who knows what convictions lurk in the hearts of man?

- The birds know, Jonathan. The birds know.

Q&A

Better Living Through Recession

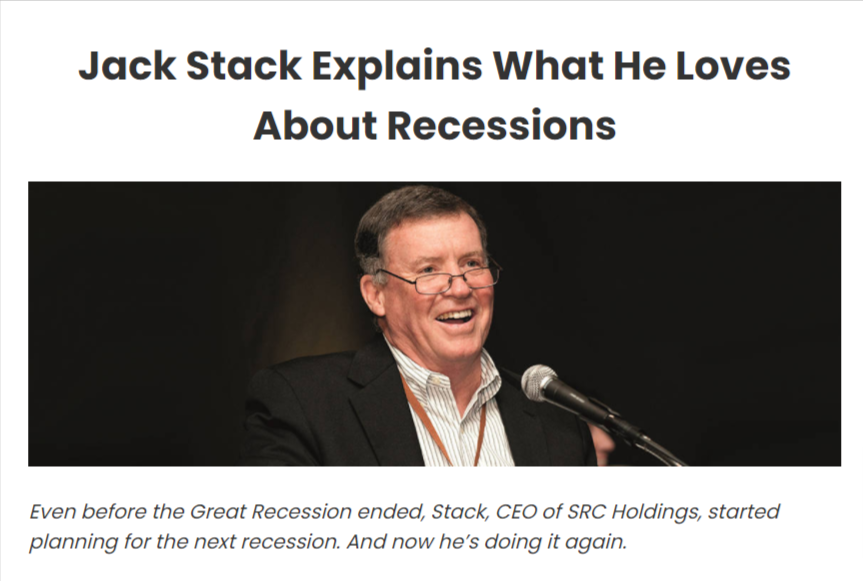

Asher again. One of the things we're interested in doing here on Heat Death is bringing you neat cuts from our respective work and back catalogues. Recently, Saul has been dipping his foot into business reporting, and came out with an interview with the Seussically named Jack Stack, who in 1983 led a group of employees to purchase a Missouri engine factory that was about to be shut down by its parent company. Stack is now the CEO of SRC Holdings, an employee-owned operation with a philosophy of management and investment that actively plans around recessions.

You can find the piece here. it's a quick and interesting read, even for a person who isn't very attuned to business reporting, like me. Saul and I sat down to talk about it, and how rolling with the punches means understanding that you are, in fact, going to get punched.

Asher: You aren't someone who people generally think of as writing about businesses. So how did you pick up this story? What interested you about it?

Saul: Well, first off, you don't make a living in journalism by being reluctant to write about new things. That means in part that when one of my old editors—former New York Times business editor, Loren Feldman— told me he was starting a business publication and could pay well, I jumped on board. He asked me to write about Stack's theory of open book management, and planning for recessions, back in 2019, when the idea of planning for recession seemed both hypothetical and a bit quixotic. Because the piece ended up being delayed for various production reasons for almost a year, we were able to have a series of conversations and I was able to watch in real time as they put this strategy into effect.

I realized from this piece that by declining to cover business for so long, I'd left a good bit of the story on the table. What fascinated me about Stack is that he really wanted to create an intelligent, emergent organization — it really jibed in an interesting way with some of the work I've been doing on new movement styles.

Stack runs an employee-owned company. How is that different from the more familiar model, in theory and in practice?

In the familiar model, to be a bit crude here, the boss owns the facility and sets the priorities, and workers get along with [management's priorities]. It's top down and hierarchical. SRC has some aspects of that approach -- it's hard to get away from it entirely -- but has worked very hard to make sure that the company's core mission and strategy is arrived at democratically. Every worker has enough of a sense of that big picture that they can work relatively autonomously and creatively to bring it to life -- and because they collectively own the company, they benefit from its wins.

This works in practical terms as a kind of information tech.

Unpack that.

Sure. Let's think of it this way: in terms of how information moves within an organization, and how decisions get made. The idea is, no one has a better sense of how any part of the company is doing-- what problems are inherent to a department, and what opportunities -- than the people working there. So how do you make it so that they can do as much as possible on their own?

In a traditional organization, this is a constant problem — they have to be motivated to tell management, which has to assign them resources: a request goes up the chain, resources come down. But why does the employee care enough to tell their manager? Do they feel empowered to solve problems themselves?

So this isn't just "listening to employees," which is generally bullshit, but actually distributing power to them.

Yeah, which is a very practical decision. In a sense, this is closer to how your body makes decisions. If a glass is falling off the counter, my hand reaches out to grab it before my mind is fully aware. If I have a bacterial infection, my T-Cells hunt down the intruders and kill them without asking my conscious mind for clearance.

SRC's approach is in no sense politically radical. Distributing power was a necessary step they had to take in order to get everyone on board to buy the company when it was otherwise going to go out of business. Stack came down to SRC and pretty early found out that it was going to have to be shut down. They scraped together a big loan to buy out the company that had owned it -- but then had to climb their way out from under that mountain of debt.

Raising the money from employees required giving them buy-in. But the bigger issue was making sure that everyone was on board to pay back that loan, and making the company solvent as a cooperative required some radical rethinking about structure.

Talk to me about the idea of recessions as opportunities. I think that can leave a bad taste in people's mouths--it sort of summons up the idea of vulture capitalists profiting off of people's misery. What are some lessons here we can draw about planning for decline?

I think the first thing I'd say is that a more malignant trend in American business thinking is the one that we grew up with in the run up to the Great Recession, which was the folk idea that the economy will never falter, and it's just expansion and roses from here on out.

Right. The market can't fail, it can only be failed.

Yeah. Whereas another way of thinking about it is that decline and fall are part of the usual order of things. And that if you accept that, and work it into your thinking, then it starts to change the way that you plan, and therefore the way that you spend. It means that you are conservative about growth, and don't hire a bunch of people who you may soon have to fire -- until, that is, you're going to rapidly scale up operations to meet a new niche that's opening up.

And once that opportunity comes, if you are like SRC, you have a lot of cash in the bank that now—because you've waited for a recession and other people weren't prepared for it—other people want to sell you their ailing assets for.

To make a sort of obvious ecological point, the idea of the vulture capitalist kind of elides the fact that vulture capitalists, like the birds, also profit off of misfortune, but they also provide a larger service to the ecosystem. Eating the dead is morally neutral.

But SRC also is following a very concrete model--you're moving into a space where you're building things, not buying up abstracted debt. Or farming debt, for that matter.

Right, and that's the other important thing. They are buying real assets which they're going to use to either make real objects or to have real third-party businesses. I mean, this is a company whose core business is engine parts. They're not in the more abstract areas of the economy.

Abstraction is, I think, one of the windmills we're tilting at with Heat Death: it feels like large sectors of our business culture are pretty abstracted from the material world.

And this is where I think SRC's management structure really helps: I suspect that having decision making distributed throughout the entire organization helps serve as a check on those dangerous levels of abstraction.

Because the employees who are working on the ground are helping drive policy?

Right. They're empowered, in the most literal sense of the word. They have, as Nassim Nicholas Taleb likes to say, skin in the game.

It's very interesting that Stack seems pretty blase about the shift away from carbon.

Isn't it? But that's the same as the recession thing. He says, "We're going where the puck is going to be, not chasing the puck." He is in a high-carbon industry. But on the other hand, they have worked very hard over the last 30 years to have a diversified and nimble operation that's able to bring on and discard business products as needed.

You asked at the beginning what I found compelling about covering business. I think the main answer is that when you're dealing with companies who actually make things, then there is a certain refreshing empiricism and how they look at the world. In a sense everything is being subjected to the simple evolutionary test of whether it works in the market.

So it's not just about not having an overly abstract view: it's about not having an ideological view of what the market should be.

Right. The market is what it is, and what it is now isn't necessarily what it'll be in 10 years, and if you have evidence of a clear emerging trend -- well, even if that negatively impacts where you're at now, you can argue with it or you can fall into line and work with it.

But one thing that's worth saying — and I think this is a really key difference between SRC and other midsize manufacturing companies and the big titans of the carbon economy — is that SRC really doesn't have an ability to slow or stop the transition off of carbon. So it makes the most sense for them to work on servicing their existing, but presumably soon declining, high carbon operations. And meanwhile, over the next decade, they're bringing new products, like say hydrogen fuel cells, online.

But a big company like BP or Shell is in a really different position. They are big enough to seriously change the legislative or regulatory environment to slow the transition.

Was there anything in particular that surprised you when you were reporting this piece?

It surprised me how you can reach all of these ostensibly very progressive positions — cooperative ownership, rapid decarbonization — by means of a very conservative stream of practical business thinking. SRC didn't adopt these policies for abstract or ideological reasons. They adopted them because they thought they would work, and they kept them because they did. It's a refreshing example of a sort of middle American practicality that I think gets short shrift in our current media and political culture.

When I started reporting in 2019, I could see in sort of an intellectual way the benefit of their approach, but it was impossible in the middle of a fat year to really imagine what a lean year would be like, or that it might be a lot closer than we thought. But SRC, meanwhile, had been slowly planning ever since 2008, when by the way they doubled the size of the company.

Which is sort of the point of SRC's strategy, I suppose: the lean years are always closer than you think.

Remember where that idea of the fat years and the lean years comes from: the Biblical story of joseph, in the book of Exodus. And what does Joseph do during the fat years? He starts assiduously putting surplus aside. You have to imagine that during that period, people must have been annoyed that they weren't getting to enjoy the full fruit of the boom because the surplus was getting scooped up to get put into grain storehouses

Right. Building redundancy is always a bummer! But it's more of a bummer if you don't do it.

To spin this out further: you could say that Joseph and Pharaoh had the benefit of revelation, but in a capitalist economy -- or an ecosystem of any sort -- it doesn't take any particular revelation to know that lean times always come again. It does, however, take a lot of discipline to act on that wisdom when everything around you is in full ecstatic boom.

On that happy note, that's all for Heat Death this week. If you like what we're doing, please feel free to drop us a line at brothers@heatdeath.xyz (And if you've got friends you think would like this, why not invite them to sign up?)

Member discussion